Excessive use of alcohol in the workforce can undermine employee health and productivity in the form of impaired performance of work tasks, accidents or injuries, poor attendance, high employee turnover, and increased healthcare costs (1, 2). To be able to reduce the costs related to problem drinking, it is of vital importance to understand the causes of employee alcohol use. Previous research has emphasized the need for examining the processes linking occupational strain to substance use and mental health problems (3). In response to this call, this prospective study investigated job demands as predictors of psychological distress and alcohol consumption by integrating the Job Demands–Control model (JDC) (4) and the Tension-Reduction theory (5) in Frone’s conceptual framework for a moderated mediation model on alcohol use (1). Specifically, the current study will add to the knowledge about the causes of alcohol use by testing a model proposing that high levels of work demands have an indirect association with alcohol consumption through increased psychological distress and where this indirect relationship is conditioned by perceived levels of job control.

The majority of studies on the role of work factors on alcohol consumption to this date have assessed the overall direct relation between various stressors and different dimensions of alcohol use (1). A recurring result in some studies is that jobs characterized by low complexity and control and high demands are related to higher employee alcohol use (6–8). Yet, findings are inconsistent and no clear pattern exists across studies. According to Frone (1), this inconsistency can be explained by two important inherent limitations in the simple cause–effect model, which hinder our understanding of how work factors influence alcohol use.

First, the model is based on the premise that work stressors are causal antecedents of alcohol use for all employees. Although most adults consume alcohol, it is unlikely that all alcohol use is a response to work stressors. Following transactional models of stress (9), it is far more probable that employees who lack certain resources or who have certain vulnerabilities will use alcohol to cope with work stressors (1). For instance, while some studies have reported direct relationships between high levels of work demands and increased alcohol consumption (6, 8), it is possible that this association is dependent upon moderating factors such as personality, coping styles, religious views, job control, social support, or role ambiguity. A second limitation of a direct-relationship model between work stressors and alcohol use is that no information is provided about why work stressors cause increased alcohol consumption. That is, it does not account for potential intervening variables such as negative affect, anxiety, and depression (1).

As the causes of alcohol use are complex and multifold, the above limitations of a direct-relationship model between work stressors and alcohol use suggest that it is necessary to include moderating and mediating factors in order to fully understand the mechanisms that explain when and how adverse working conditions can lead to increased alcohol use (1). With regard to moderating factors, the JDC model (4, 10) suggests that job control, ie, the degree to which a worker has the possibility to deal with such demands (decision latitude), plays an important role with regard to job demands outcomes. The rationale for this model is that job control moderates the impact of job demands on strain in that high level of control allows the individual to cope with high demands. The most adverse reactions (fatigue, anxiety, depression, and physical illness) will occur when the psychological demands of the job are high and the worker’s decision latitude in the task is low (11). These undesirable reactions, which arise when arousal is combined with restricted opportunities for action or coping with the stressor, are referred to as psychological strain (12). The hypothesis that combinations of high demands and low job control are risk factors for psychological strain is supported by extensive empirical evidence (for reviews and meta-analysis see 11, 13).

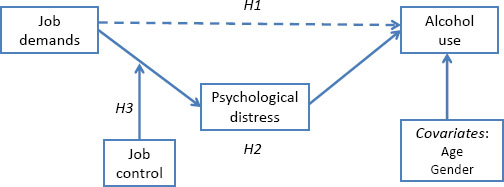

A substantive body of research has established that high levels of psychological strain are associated with increased substance use, especially alcohol consumption (8, 14). Following the Tension-Reduction theory (5), a possible explanation for this relationship is that alcohol is consumed to reduce strain. That is, as alcohol is a central nervous system depressant that may resolve psychological tension and even induce euphoria, individuals may use it for self-medication to lower levels of distress and anxiety. By integrating the Tension-Reduction theory with the JDC model, psychological strain in the form of distress emerges as a potential mediating factor between adverse working conditions and alcohol use. Although few studies have examined the intervening role of mental distress in the relationship between job demands and alcohol use, distress has been established as a significant mediator in other stressor–strain relationship (eg, 15, 16). In addition, mental distress has been established both as a result of high job demands and a predictor of alcohol use. For instance, in meta-analytic summary of the prospective evidence of mental disorders as an outcome of psychological job demands, Stansfeld and Candy (11) concluded that high levels of job demands were positively associated with subsequent mental disorders. With regard to distress as a potential predictor of alcohol use, comorbidity between distress, in the form of anxiety and depression, and alcohol consumption has been reported (see 17) although there is lack of consistent longitudinal evidence (14). Still, as the JDC model and Tension-Reduction theory point to a relationship between job demands, job control, mental distress, and alcohol use, we suggest that job demands have an indirect association with alcohol use through mental health problems, and that the magnitude of this indirect relationship is dependent upon levels of job control (see figure 1). In order to examine this theoretical relationship, the following hypotheses will be tested in both cross-sectional and prospective data: (i) H1: job demands are positively associated with alcohol use; (ii) H2: the association between job demands and alcohol use is mediated by mental health problems (indirect association); and (iii) H3: the indirect association between job demands and alcohol use through mental health problems is moderated by levels of job control (conditional indirect association) in that there will be a stronger indirect association between high levels of job demands on alcohol when levels of job control are low.

Method

Procedure and participants

The present study is based on data from a large sample of Norwegian adults employed in a full- or part-time position. The survey was web-based, although participants with limited access to computers at work were given the option of completing a paper version of the questionnaire. Subjects were recruited from 91 organizations, representing a wide variety of job types, comprising among others municipalities, insurance companies, health institutions, and public organizations. The survey design was a full-panel prospective with all variables measured at two time points. The average time-lag between the measurement points was 24 months (range: 17–36 months). Employees and management in the companies were informed at the organizational level first (for a further description of the survey, see 18).

All employees, excluding those on sick leave, were mailed a letter with information about the survey. This letter contained either a personalized code for logging into the web questionnaire or a paper version of the questionnaire with a pre-stamped return envelope, in addition to information about the survey. The written information explained the aims of the study and assured that responses would be treated confidentially, in strict accordance with the general guidelines and specific license from the Norwegian Data Inspectorate. At the time of data analysis, 19 390 employees had been invited to participate in the baseline survey, of which 11 090 responded (57.2%). Altogether 6283 persons have so far been invited to participate in the follow-up survey, with a total of 4328 positive responses (69%). Only those who responded to the questions about alcohol use at baseline and follow-up were included in this study (N=3642).

About 85% of the sample responded to the survey using the electronic survey form. Mean age in the total baseline sample was 44 [standard deviation (SD) 10.8, range 18–73] years. The sample consisted of more women (60%) than men (40%). Breakdown in years of education was: 1–9 years (5%); 10–12 years (33%), 13–16 years (43%), and >16 years (19%). The majority of the sample (93%) reported to be in regular full-time employment, and about 87% were on daily working time arrangement. Altogether 21% had a leadership position with personnel responsibilities. The overall sample characteristics suggest that the sample is quite heterogeneous and thereby representative of Norwegian working life in general.

Attrition analyses from baseline to follow-up showed that participants in the follow-up assessment had significantly higher average alcohol consumption (t=3.89; df=5,536; P<0.001), job control (t=7.56; df=6,061; P<0.001), and lower levels of psychological distress (t=-2.73; df=5,517; P<0.01), compared to non-participants. No differences were found with regard to job demands (t=1.61; df=6,128, P>0.05) or age (t=0.18; df=9,431; P>0.05) between the groups.

Ethics statement

The Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REK) in Norway approved this project. The Data Inspectorate of Norway gave consent and the study was conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. All study participants provided their informed consent. When accessing the web-based questionnaire using a personal login code, individuals had to provide informed consent before responding. The Data Inspectorate and REK approved this procedure and data were analyzed anonymously.

Instruments

Employee alcohol use was measured with a single item asking about how many units of alcohol the respondents consumed in a regular week. It was explicitly specified that a unit of alcohol is 10–15 grams of ethanol and that this corresponds to about 0.5 liters of beer, one glass of wine or one shot of liquor.

Job demands (7 items) and job control (8 items) were assessed with previously validated scales from the General Nordic Questionnaire for Psychological and Social Factors at Work (QPSNordic) (19, 20). The job demands scale (Cronbach’s alpha T1/T2=0.76/0.76) included items which assessed the respondents’ experience of quantitative demands (ie, time pressure and amount of work) and decision demands (ie, demands for decision-making and attention). Sample items include ‘‘Do you have too much to do?’’ and ‘‘Does your work require quick decisions?”. The job control scale (alpha T1/T2=0.80/0.82) included items which assessed the respondents experience of decision control (ie, influence on decisions regarding work tasks, choice of coworkers, and contacts with clients) and control over work intensity (ie, influence on time, pace, and breaks). Sample items include “Can you influence the amount of work assigned to you?” and “Can you set your own work pace?”. The scales were constructed on the basis of the following frequency scoring: ‘‘1=very seldom or never”, ‘‘2=somewhat seldom”, ‘‘3=sometimes”, ‘‘4=somewhat often”, and ‘‘5=very often or always”.

Psychological distress during the last week was measured with the 10-item version of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL-10). The HSCL is a valid, reliable (21), and widely used self-administered instrument designed to measure mental distress in population surveys (22) with 90-, 58-, 35-, 25-, 10-, or 5-item versions. Comparisons of HSCL-25, HSCL-10, and HSCL-5 have shown that the shorter versions perform almost as well as the full version (23). The HSCL-10 consists of 10 items on a four-point scale, ranging from “1=not at all” through “a little” and 3 “quite a bit” to “4=extremely”. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.86 at both baseline and follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics 21.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Although a full analysis of an indirect process requires at least three waves of data, two-wave studies offer some indication of the presence and direction of a potential indirect relationship (24–26). Compared to cross-sectional assessment of indirect associations, a model based on two measurement points represents a significant improvement in inferential power as one is able to control for prior levels of variables and examine the significance of the influences on the change variance of the mediator and the outcome (26). The longitudinal test of the hypothesized moderated mediation model was conducted by following Little’s recommendations (26).

Data were analyzed by means of the PROCESS script developed for SPSS (27). PROCESS uses an ordinary least squares or logistic regression-based path analytical framework for estimating direct and indirect associations in simple and multiple mediator models, two- and three-way interactions in moderation models along with simple slopes and regions of significance for probing interactions, conditional indirect associations in moderated mediation models with a single or multiple mediators and moderators, and indirect associations of interactions in mediated moderation models also with a single or multiple mediators (see www.afhayes.com for further description and documentation). Bootstrap methods were implemented for inference about indirect associations in both unmoderated as well as moderated mediation models. Interferences were based on bootstrap accelerated confidence intervals (BCa). Bootstrapping is a statistical procedure that allows you to calculate effect sizes and hypothesis tests for an estimate even when you do not know the underlying distribution (27). Bootstrapping was set to 5000 resamples in all analyses. For the sake of interpretability, independent variables were standardized prior to analyses.

It has previously been noted that studies on associations between stress and alcohol have not controlled for potential confounding variables (1). Sociodemographic characteristics such as age and gender may influence both the likelihood of holding a stressful job and rates of alcohol use, creating a spurious relationship between work stress and alcohol outcomes (1, 28). In the current study all analyses of relationships between work factors were controlled for potential age and gender effects. In our prospective analyses we also statistically corrected for the baseline score of the specific time-2 dependent variable. To further control for confounding factors, separate subgroup analyses of the study hypotheses were conducted for gender, educational level, and alcohol use.

Studies have shown that alcohol abuse increases the risk of psychological distress (29), possibly due to the direct neurotoxic effects of heavy alcohol exposure to the brain (30), a reversed relationship between alcohol use and psychological distress seems likely. Hence, it is possible that employees increase their alcohol consumption in response to adverse working conditions and that this increased use of alcohol subsequently influences mental health. In order to rule out this alternative explanation, we also tested a model in which there is an indirect relationship between work demands and subsequent distress through alcohol use.

Results

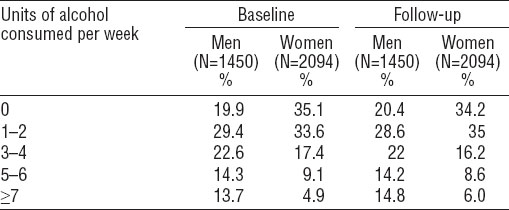

The prevalence of alcohol consumption at baseline and follow-up for men and women is reported in table 1. Men reported significantly higher alcohol consumption than women at both baseline (X2=183.81; df=4; P<0.001) and follow-up (X2=177.64; df=4; P<0.001). The majority of the male respondents reported an average alcohol consumption of ≤4 units per week, whereas the majority of female respondents reported an average consumption of ≤2 units of alcohol per week, at both measurements points. About 29% of respondents were abstainers. At baseline, 13.7% of men and 4.9% women reported a consumption of ≥7 units per week. The corresponding numbers at follow-up were 14.8% and 6%.

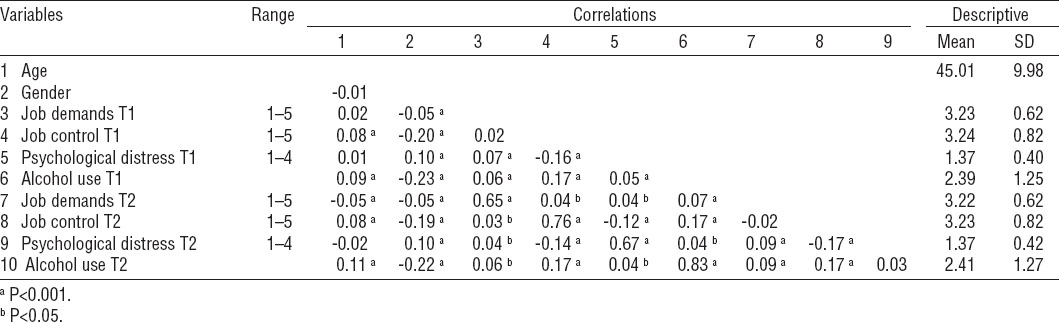

Means, SD, and inter-correlations between study variables are presented in table 2. On a scale of 1–5, the average levels of job demands were 3.23 at baseline and 3.22 at follow-up. Average levels of job control were 3.24 at baseline and 3.23 at follow-up. These numbers are in line with findings from previous validation studies of the QPSNordic (19, 20). On a scale of 1–4, the average levels of psychological distress were 1.37 at both baseline and follow-up. Yielding some support to H1, job demands at baseline were positively but weakly associated with alcohol use at both baseline (r=0.06; P<0.001) and follow-up two years later (r=0.06; P<0.001). The correlations analyses showed small associations between job demands and other study variables. The low correlations between job demands and control are in line with other studies based on the QPSNordic (eg, 20). Job control at baseline correlated moderately with alcohol use (r=0.17; P<0.001), whereas small associations were established with regard to the other variables. All study variables had relatively high stability between baseline and follow-up.

Tests of hypotheses in cross-sectional data

As a first test of H2 (ie, whether job demands have an indirect association with alcohol use through psychological distress), a simple cross-sectional analysis of indirect pathways with psychological distress as the intervening variable was conducted in the baseline sample (N=3428). After controlling for age and gender, job demands exhibited significant direct associations with psychological distress (B=0.08; P<0.001) and alcohol use (B=0.06 P<0.01), whereas job control was positively related with alcohol use (B=0.15; P<0.001) and negatively related with psychological distress (B=-0.06; p<0.001). Psychological distress was positively associated with alcohol use (B=0.08; P<0.001). Age was significantly related to alcohol use (B=0.01; P<0.001), but not to psychological distress (B=0.00; P>0.05). Gender was related to both psychological distress (B=0.21; P<0.001) and alcohol use (B=-0.60; P<0.001). In the analysis of indirect associations, job control was specified as a moderator of the relationship between job demands and psychological distress. In this analysis, a small but significant indirect association between job demands and alcohol use through psychological distress was established (B=0.006; 95% BCa CI=0.003–0.012). This indirect association was supported by a significant normal theory test (Z=2.92; P<0.01). Although evidence for indirect pathways was found, the overall magnitude of this indirect relationship was very small.

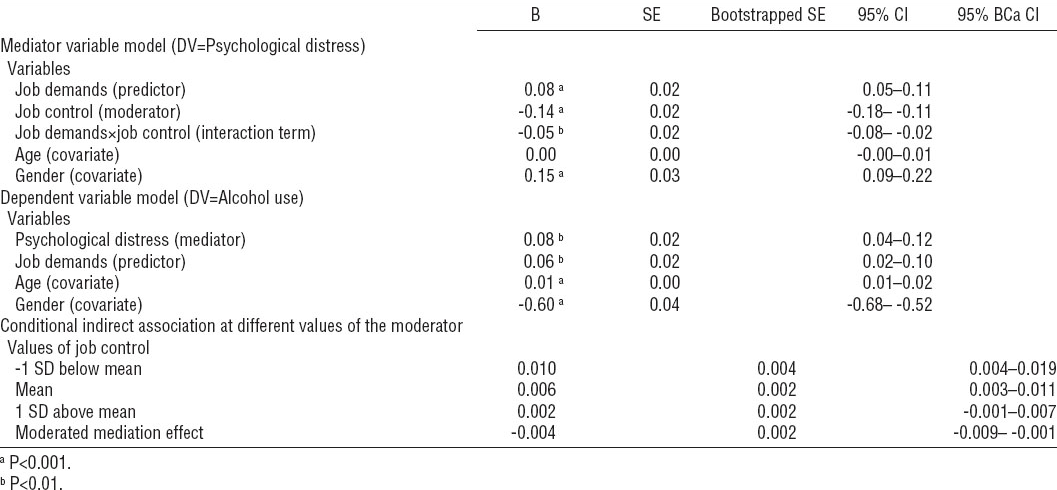

In order to test H3 (ie, whether the indirect association between job demands and alcohol use through psychological distress is dependent upon job control), job control was included as a moderator in the regression model. In the moderator analyses, the values of the moderator variable were set at mean and one SD above and below the mean (31). Job demands (B=0.08; P<0.001), job control (B=-0.14; P<0.01), and the interaction between job demands and job control (B=-0.05; P<0.001), significantly predicted levels of distress. The conditional process index provided support for a significant moderated mediation effect (B=-0.004; 95% BCa CI= -0.009– -0.001) and thereby H3. BCa CI were calculated to determine the values of the moderator at which the conditional indirect association was significant. As displayed in table 3, significant indirect relationships through psychological distress were established for the low- and mean-control conditions. No evidence for an indirect association was found for the high-control condition.

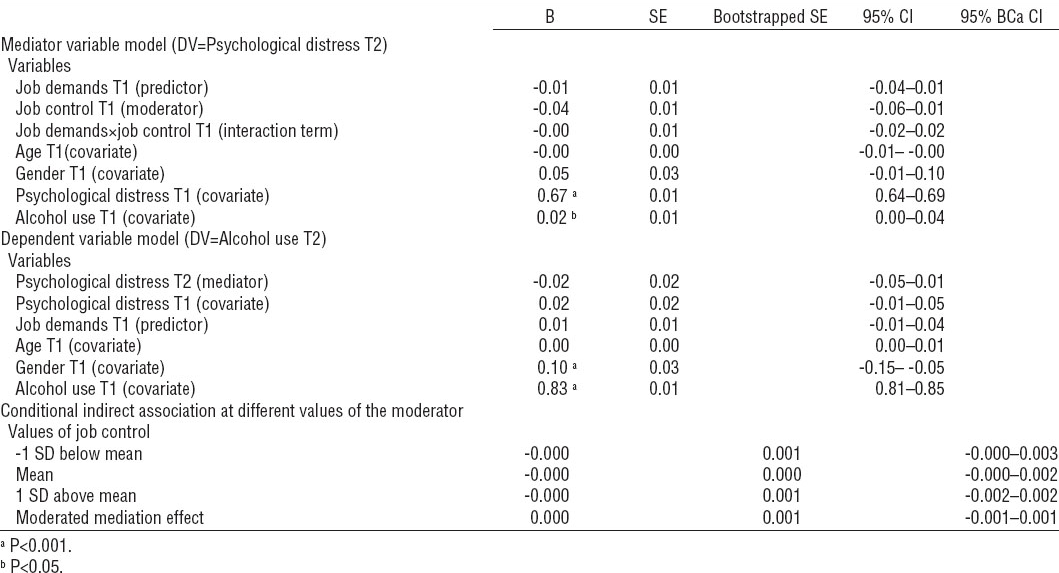

Tests of hypotheses in prospective data

To add to the understanding of the causal directions of the associations between study variables, the above analyses were repeated with the use of prospective data. Here, job demands at baseline were used as predictor variable, whereas alcohol use at follow-up was included as the outcome. Psychological distress at follow-up comprised the mediator, while job control at baseline was used as moderator. After adjusting for control variables and the score of the outcome variable at baseline, analyses of direct associations (H1) showed that baseline job demands was related to neither psychological distress (B=-0.01; P>0.05) nor alcohol use at follow-up (B=0.01; P>0.05). Job control was positively related to alcohol use (B=0.03; P<0.05) and negatively related to psychological distress (B=-0.02; P<0.05). No significant associations were found between psychological distress at baseline and alcohol use at follow-up (B=0.02; P>0.05). The test of the potential indirect associations (H2) between job demands and alcohol use through psychological distress provided no evidence for distress as an intervening variable (B=-0.000; 95% BCa CI= -0.000–0.002; Z=0.72; P>0.05). Going against H3, job control did not moderate this association (B=-0.000; 95% BCa CI= -0.001–0.001). The findings from the full moderation mediation analysis of prospective data with alcohol use as the outcome variable are displayed in table 4.

Additional analysis

To determine a potential reverse association between study variables (eg, whether alcohol use is related to subsequent reports of job demands or whether job demands have an indirect association with subsequent psychological distress through alcohol use), a series of alternative models were tested in the prospective dataset. In analyses of direct association, alcohol use at baseline was significantly related to job demands two years later (B=0.03; P<0.01) after controlling for baseline job demands, age, and gender. Psychological distress was not associated with later job demands (B=-0.01; P>0.05). In follow-up analysis where psychological distress was tested as a mediating variable between alcohol consumption at baseline and later job demands, we found no indications of a mediating effect of distress (B=-0.002; 95% BCa CI= -0.000–0.005; Z=0.72; P>0.05). Finally, we tested a longitudinal model in which alcohol use was specified as the intervening variable and psychological distress as the outcome variable. Alcohol use, psychological distress, age, and gender at baseline were included as control variables. The findings showed that alcohol use did not mediate the association between baseline job demands and subsequent psychological distress (B=-0.000; 95% BCa CI= -0.002–0.000; Z=-0.63; P>0.05), and there was no evidence of a moderating effect of job control (B=-0.000; 95% BCa CI= -0.001–0.000).

In order to provide comprehensive and robust tests of our hypotheses, the tests of mediation and moderated mediation where repeated in different subgroups of the sample. Specifically, separate analyses were conducted among men and women, in different sociodemographic groups as classified by level of education, and finally in a subsample that only comprised workers who reported to have used alcohol. In the gender-specific analyses of cross-sectional data, job demands had an indirect association with alcohol use through psychological distress among women (B=0.006; 95% BCa CI=0.002–0.012; Z=2.59; P<0.01), but not among men (B=0.005; 95% BCa CI= 0.000–0.015; Z=1.56; P>0.05). Job control functioned as moderator of the relationship among women only (B=-0.004; 95% BCa CI= -0.010– -0.001). Hence, with regard to the study hypotheses, the findings from the cross-sectional analyses provided support for H2 and H3 among women, but not men. The gender specific analyses of prospective data replicated the findings from the main analyses in that no moderated or mediating associations were found.

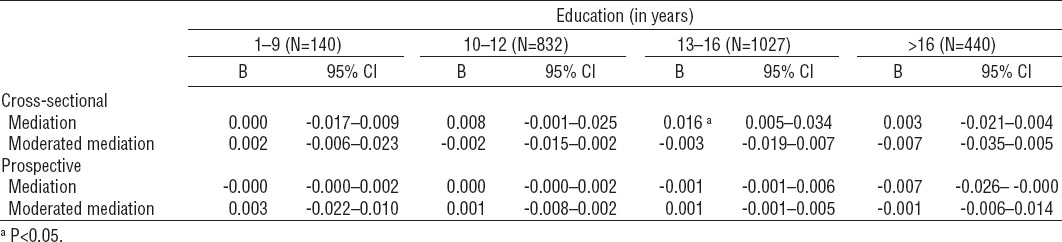

In the education specific analyses, respondents where categorized into four different groups based on their level of education: elementary school (1–9 years; N=140), high school (10–12 years; N=832), college or university (13–16 years; N=1027), and higher level college or university (>16 years; N=440). As summarized in table 5, evidence for cross-sectional indirect associations (H2) was only established in the “13–16 years of education” subsample, although the magnitude of this relationship was quite small. No support for H2 or H3 (ie, for indirect or moderated associations) was found in the prospective data.

Table 5

Analyses of mediation (Hypothesis 2) and moderated mediation (Hypothesis 3) in different educational groups.

Non-drinkers are a heterogeneous group that comprises both lifelong abstainers who choose not to drink alcohol for religious or conscience reasons, as well as people who do not drink alcohol due to previous alcohol addiction or ill health (14). To be able to control for the potential impact of non-drinkers, the analyses were also replicated in an alcohol-users-only subsample. As for psychological distress as a mediator (H2), a significant cross-sectional indirect association was established in this sample (B=0.008; 95% BCa CI= 0.004–0.015; Z=3.13; P<0.01). Supporting H3, this cross-sectional association was moderated by job control (B=-0.006; 95% BCa CI= -0.013–0.02). No mediated or moderated associations were found in the prospective data for this subsample.

Discussion

Based on the JDC model and Tension-Reduction theory, the primary goal of the current longitudinal study was to determine (i) whether the relationships between job demands and alcohol use (H1) is mediated by psychological distress (H2), and (ii) if this association is dependent upon levels of job control (H3). Providing some support to the study hypotheses, job demands had an indirect cross-sectional association with alcohol use through psychological distress and this association was moderated by job control. Supporting the JDC model, the indirect association was strongest among respondents with low job control. Subgroup analyses indicated that this association was dependent upon both gender and educational level. Specifically, this conditional indirect association was only significant among women and in the “13 to 16 years of education” subsample. Yet, the magnitude of these significant associations was small.

Analyses of prospective data in the overall sample provided no evidence for direct, indirect, or moderated relationships between exposure to job demands and alcohol use two years later. Similarly, analyses of alcohol use as a potential mediator of the relationship between working conditions and mental distress did not support such an alternative causal model. Subgroup analyses provided no further indications of time-lagged indirect or conditional associations. Taken together, while the cross-sectional findings were partially consistent with the study hypotheses, no supporting causal evidence could be derived from the prospective analyses.

Although we had strong theoretical reasons for expecting an association between work stressors and alcohol use over time, there may be several explanations for why this relationship was not found in the current study. First, it is possible that job demands simply have a limited impact on later alcohol consumption. This explanation is in line with other empirical data which have provided little support for an association between work stressors and alcohol use (3, 8, 28). Still, it should be emphasized that our study represents an important contribution to the existing literature. That is, whereas previous research mainly has tested direct relationship between work factors and alcohol use in cross-sectional data, this study included comprehensive tests of both direct, indirect, and moderated long-term association between the variables in question without finding any robust relationship. Yet, it should be noted that indirect associations have been found to be strongly underestimated when estimated with two-wave prospective data, and three-wave data are more appropriate for determining indirect associations (24). Hence, upcoming research should test the study hypothesis in a three-wave study.

The limited relationship between exposure to job demands and alcohol use may also be due to unobserved variables. The present study investigated the moderating role of job control on the association between job demands and alcohol use and conducted separate analyses for gender, educational levels, and alcohol use. Still, there may be many other moderating factors which have the potential to influence the magnitude of the relationship between job demands and alcohol use. Building on theories of coping (9, 32), there are reasons to expect that the use of different coping strategies will influence relationship between work exposure and subsequent consumption of alcohol. For instance, it seems quite likely that an individual propensity to use substances and alcohol as a way to cope with challenging situations influences the strength of the relationship between exposure to stressors and alcohol use. Other potential moderators include intrinsic job motivation, family history of abuse, personality traits associated with low self-control and specific genetic factors (3, 33, 34).

The limited associations between the study variables could also be due to methodological factors. First of all, the findings may be influenced by the time period between the baseline and follow-up surveys. The present study tested associations with a two-year follow-up period, a time lag which has been found to be appropriate in order to determine relationships between psychosocial work exposure and individual outcomes (35). Yet, as recent research has shown that strengths of such relationships vary over time (36), it may be that other time-lags are more suitable for testing the proposed associations. As there is no clear basis upon which to forward a specific time-lag hypothesis of work-induced alcohol use, both shorter and longer time lags than in the current study may be relevant. For instance, severe exposure at one time point may cause immediate or short-term changes in alcohol consumption, whereas long-term exposure may gradually cause a pattern of maladaptive drinking. As we found some support for our hypothesis in the cross-sectional data, it seems possible that a shorter time-lag would have uncovered stronger relationships between the study variables.

The use of a global and context-free measure of alcohol use is another methodological factor which may have influenced the results. It has previously been argued that such overall measures largely capture variation in alcohol use that is unrelated to exposure to work stressors during the workday, and that context-specific measures are more appropriate to examine work related alcohol use (1). Illustrating the importance of measurement methods, Frone (8) found no support for the Tension-Reduction hypothesis when using a context-free assessment of substance use, whereas the hypothesis was supported when utilizing a workplace context-specific measure. In order to shed light on these methodological issues, future research should replicate the current study by using context-specific assessments of alcohol use and employing other time-intervals between measurement points.

Methodological considerations

The present study assessed work factors and alcohol consumption in an extensive sample of Norwegian employees from a range of different industries using well-established measurement instruments with a response rate above the mean of organizational surveys (37). However, although the sample is large, non-random sampling methods have been utilized, thus limiting the external validity of the findings. As attrition from baseline to follow-up was non-random, this could also influence the external and internal validity of the findings. For instance, as participants at follow-up reported higher levels of alcohol consumption while they simultaneously had more positive experience of job control compared to drop-outs, there are reasons to suspect selection bias may have influenced the findings of the study.

As all included measurement instruments are self-report measures, the study is limited by the problems that are specific to self-report instruments such as response set tendencies. For instance, it is possible that some misclassification of alcohol intake may have influenced our findings as underreporting of alcohol use is common in population-based studies and especially among heavy drinkers (14). As for the measures of job demands and job control, the QPSNordic instrument used in the current study should be fairly insensitive to respondents’ emotions or personality dispositions. QPSNordic-items are constructed with the aim of avoiding emotion and social desirability bias in that subjects report frequency of occurrence rather than degrees of agreement or satisfaction and items do not address issues that are inherently negative or positive (38). Finally, having only two measurement points with a two-year time lag could be a limitation as this study design does not allow testing cyclic relationships between the study variables (25).

Conclusions, implications, and directions for future research

In the present study we used the JDC model and Tension-Reduction theory as a basis for investigating relationships between job demands, job control, psychological distress, and alcohol consumption. Based on analyses of both cross-sectional and prospective data, as well as extensive subgroup analyses, we conclude that perceived job demands have little direct impact on future alcohol use. Furthermore, we found no clear evidence for psychological distress as a potential mediator of the association between job demands and alcohol use or perceived job control as a moderator of the relationship. Consequently, the findings provide little support to the proposed theoretical model for how and when job demands are related to alcohol use. A practical implication of our findings, if replicated in other studies, would be that interventions against excessive alcohol use and problems with alcohol use in the workplace should target work factors other than those included in this study (ie, quantitative demands, decision demands, control over work intensity, and decision control). For instance, it may be that factors such as high levels of emotional job demands, role ambiguity, or role conflicts have a stronger impact on alcohol use. In addition, individual vulnerabilities among workers should also be taken into consideration.

As this study only represents a single contribution to the understanding of work-related alcohol use, it should be replicated in upcoming research in other samples and with other assessment methods and research designs. Hierarchical linear models may be used to rule out the potential impact of reporting bias on work factors. In addition, as previous research has shown that context-specific measures of alcohol use seems more useful than context-free measures (8), future research should determine relationships between work stressors and alcohol with methods that assess alcohol use in terms of its temporal relation to the workday. Finally, as Norway has the lowest average alcohol intake levels in Europe (39), our theoretical model may be more valid in other countries where alcohol is consumed more frequently.