The time between marriage and the birth of the first child has been used by demographers as a measure of fecundity, but such a measure only works if cohabitation and wanting to have a child are closely linked to marriage. In a world where pregnancies can be planned for those who have access to safe contraception methods, couples may know their “time-to-pregnancy” (TTP) as the waiting time from when they stopped using contraceptive methods until becoming pregnant or being classified as infertile (a period of ≥12 months). This TTP measure was first used in 1981 (1) as a measure of couple fecundity and it has been applied widely with success and failure in many areas of research including work-related fecundity problems (2, 3, 4). In this letter, some less well-known limitations of the TTP measure are discussed.

Ambiguity of time-to-pregnancy

Our estimate of TTP is usually based on a question such as “Was your pregnancy planned? and if yes, how long did it take you and your partner to become pregnant?” Responses are often fixed answering categories specifying cycles or months of waiting time and based on the assumption that pregnancies are well planned.

While the couple may know the starting time as the date of stopping contraception (or having unprotected sex), the time of conception is usually not known. Do they report the date of the last menstrual period, when a pregnancy test was positive, or when their doctor told them they were pregnant? All of these measures lead to a measure of TTP riddled with uncertainties. There is nothing unusual about this. Most of what we measure in epidemiology comes with some uncertainty. We should, however, be concerned about misclassification that causes bias, which we can illustrate using simple directed acyclic graphs (DAG) as in figures 1 and 2.

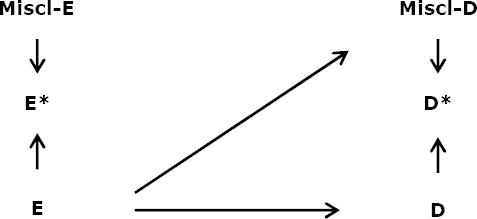

Figure 1

Misclassification measurements with no differential misclassification. [E=exposure of interest; E*=the measured exposure; Miscl-E=the factor than differentiates E* from E; D=disease (infertility measures by time-to-pregnancy (TTP); D*=the measured disease; Miscl-D=the factor than differentiates D* from D.]

Say the exposure (E) is an environmental exposure measured in blood with some lack of precision for the time period of interest (E*) and Miscl-E reflects that. Our measure of couple fecundity (D) is measured as a TTP (D*) as a time-to-conception, date of last menstrual period, or clinical pregnancy under the influence of Miscl-D, which could be age, menstrual disorders, pregnancy planning, use of contraceptive methods and more. If there is a causal link between E and D, as stated in figure 1, we will pick up an association because the path E*!E∀D–D* is open. The strength of this association may be attenuated but an association remains, driven by the causal link E∀D.

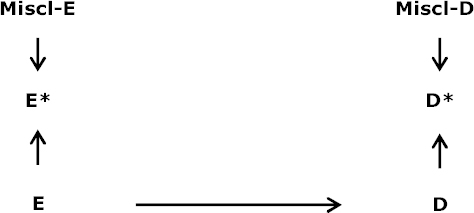

We should be even more concerned if E is related to Miscl-D as illustrated in figure 2.

Even if E and D are not causally linked (no E∀D), E* and D* (which is what we measure) will be associated because of the open E*!E∀Miscl-D∀D path. This E∀Miscl-D link may depend on which TTP we measure: time-to-conception, TTP (early or late) or their relation to E. If E causes menstrual disorders or is related to pregnancy planning or visits to the doctor/midwife, an E∀Miscl-D may be generated, which can only be controlled in situations where E itself is only indirectly causing Miscl-D by a variable that can be controlled.

A time-to-conception measure may be different from a TTP measure, partly because the couple does not know when the pregnancy began. A time-to-birth measure may solve this uncertainty because the time of birth is known. However, then you have to condition on fetal survival, which may cause other problems (5).

Pregnancy planner or a pregnancy/birth study

It is complicated, expensive and time-consuming to run a study on incident pregnancy planners unless you can recruit them through social media (6). Most studies therefore recruit women when they are pregnant or give birth as in the large pregnancy/birth cohorts. There is a price to pay for this. Not only can you not identify cases with an “all-or-nothing” effect on fecundity. More important is the variety in pregnancy planning practice (7) – couples do not just decide and then try for at least one year to become pregnant. Some couples try for a shorter time and give up, some may try again at a later stage etc. Age and parity play, as expected, a role for this planning behavior (7). For example, older, parous couples often give up after <12 months of trying while young couples trying for their first child are much more persistent. In this case, we would see older couples coming into our cohort after a few months of trying while younger couples would have a longer TTP. We would perhaps (wrongly) conclude that older couples are more fecund than younger couples rather than see the data as a reflection of their different trying-to-get-pregnant patterns.

Concluding remarks

When epidemiologists ask about TTP, they actually ask about time-to-conception and the problem is that the conception date is usually unknown. How good the guess is depends, as mentioned, on a number of conditions that need to be controlled. Asking about time-to-birth would remove this ambiguity.

The period between wanting to have a child and his or her subsequent birth is not always a continuous time before conception or seeking advice from a doctor on fertility issues. The waiting time can be interrupted, set on stand-by, or cancelled before reaching 12 months or whatever cut-point is used for diagnosing infertility. This will effect both studies of pregnancy planners and studies recruiting participants during pregnancy or at birth. A study among pregnancy planners should only include incident-waiting couples. Accepting prevalent cases would induce ambiguity in defining the source population.

The TTP measure has been an important tool in studying couple fecundity, but it is not as simple to use as we thought over 30 years ago, and we may not have identified all sources of errors yet.