Productivity loss can be broadly defined as reduced efficiency in production: less output is obtained from a given set of inputs (1). In occupational health and safety (OHS), avoiding these productivity losses is an indispensable element of the value of interventions: a healthy workforce reduces the need for costly (internal or external) replacement workers, and avoids output not being produced (eg, when no replacement is found). Whereas in the economic evaluation of healthcare, productivity effects are often excluded for ethical or pragmatic reasons (2–6), in the context of OHS, they are often a central point of focus (7). This is logical, as in this domain, investments beyond the strict legal minimum requirements are often made at the discretion of managers and shareholders, for whom productivity gains are a major element of OHS’ economic attractiveness.

However, defining and quantifying productivity change is a complex endeavor, and several approaches exist to estimate it: output-based methods, productivity in natural units, the human capital approach (HCA), the friction cost approach (FCA), the US panel approach (USP), the multiplier approach (MA), and workers’ compensation expenses (CE). The rest of the introduction discusses these methods and their challenges in turn, and table 1 indicates additional advantages and disadvantages. Note that aspects of lost-time measurement stated for CEA LT are also applicable to the HCA and FCA.

Table 1

Definition, advantages and disadvantages of productivity estimation methods. [QALY=quality-adjusted life year]

A first approach measures output change directly. However, production data are not always available or costly to obtain, while (more available) revenue data might reflect market circumstances or other effects on profits (1). In addition, defining and measuring output is not always evident (see table 1), and even with an output measure, it is difficult to link this to individual employees (for instance when work is performed in teams or projects) (8). Instead, the most common approaches to estimate productivity make use of data on labor inputs (2). In this way, they measure the effect (of occupational health improvements) upon the volume (number of hours worked) and quality (human capital) of labor. A second approach to include productivity in OHS is thus to measure “lost-work-time” and state the conclusion of the study as a cost per natural unit (eg, a cost per absent day avoided). This requires measuring absenteeism – health problems leading to reduced time at work – and (possibly) presenteeism – health problems leading to reduced performance while working (2), by means of objective data or surveys. For the latter, a wide variety of standardized instruments is available, which differ in length, scope, method, and can be disease-specific or general (9). A detailed comparison of survey instruments is beyond the scope of this review, but can be found elsewhere (2, 5, 9–13). Table 1 indicates some additional measurement challenges.

Apart from these two broad approaches to quantifying productivity change, three concrete estimation methods are suggested in economic evaluation guidelines (3). In the HCA, the monetary value of productivity losses is approximated by multiplying lost working hours or days with a relevant value of production per time unit – a “price weight” – such as individual or average wages (12). This is in accordance with the assumption (from economic theory) that the marginal revenue product of labor is proportionate to the wage (2, 3, 14). However, the HCA also implicitly assumes that changes in inputs (absenteeism and presenteeism) have a direct linear relationship with changes in output (lost production) (15), whereas compensation mechanisms can mitigate some production losses: less important tasks can be postponed and made up for on return, internal labor slack/reserves could be used, and temporary or permanent replacements can be trained and hired (15, 16). As such, some criticize the HCA because it takes a long(er) time horizon, where productivity costs can become quite substantial (eg, when they accumulate over several years) and may include lost productivity due to disability or early retirement (14). The FCA instead proposes to limit long-term production losses to the “friction period” [the time needed to replace a sick worker (16)] and to adjust shorter absence spells for the “elasticity of labor to output” – the less than proportional change in output per unit of labor – to reflect compensation mechanisms (16, 17). This friction period will likely depend on the location, industry, firm, and category of worker (3). Finally, the costs of compensation mechanisms (eg, costs of hiring workers) should ideally be included (17, 18). A third approach, the USP, argues that productivity should not be measured separately since it is part of quality of life estimates in health state utilities such as quality-adjusted life years (QALY) (2, 3, 12, 19). However, up to now, neither QALY nor the USP approach have been frequently used in OHS (20).

A theoretical model by Pauly et al gives rise to a fourth method: the multiplier approach (21, 22). It poses a critique on salary conversion methods, such as the HCA and the FCA, by stating that the cost of absenteeism can be “higher than the wage when perfect substitutes are not available to replace absent workers, and there is team production or a penalty associated with not meeting an output target [for a given time interval]” (21). Job-dependent wage multipliers have been suggested – and to a certain extent estimated – to correct for this underestimation (15, 21, 22). However, while the empirical impact of wage multipliers has been demonstrated (13, 15, 23), little research has been done on how to include them, especially in the case of presenteeism (5, 24).

Some studies make use of compensation expenses data (20). The regulations for workers’ compensation differ strongly region by region (25, 26) and the expenses are often a mix of replacement wages, disability benefits, insurance expenses and healthcare costs. They can be included directly in the analysis (eg, by using the total sum of compensation expenses) or can be calculated per employee and used as the price weight for valuing lost-time (ie, a variant on the HCA). While compensation data can be easy to collect, the size of these payments is not necessarily related to the loss of productivity capacity (20, 26) and can give rise to contaminated absence data, since some datasets will only contain “compensated days” instead of all sick leave.

While all approaches estimate the marginal effect of the intervention upon productivity, they can also be seen as fulfilling distinct purposes, and the appropriate method may depend on the intervention, outcomes, perspective, time horizon, study design, etc (14). It might even be interesting to use several methods (eg, the HCA and FCA) (3, 5) or to combine them. For instance, the FCA can include additional measures to control for compensation mechanisms (correcting not only for long-term replacements, but also for colleagues’ work), or can use job-dependent multipliers.

Earlier studies have systematically reviewed how the economic evaluation literature of OHS, up to 2007, estimates productivity change. These authors observed significant diversity within different applications of the same methods, thereby hindering comparability of results and decision-making and ample margins for improvement (12, 17, 20). In this article, we aim to extend on these studies by reviewing economic evaluations of OHS interventions that have emerged in the decade after the last review (2007–2017).

Methods

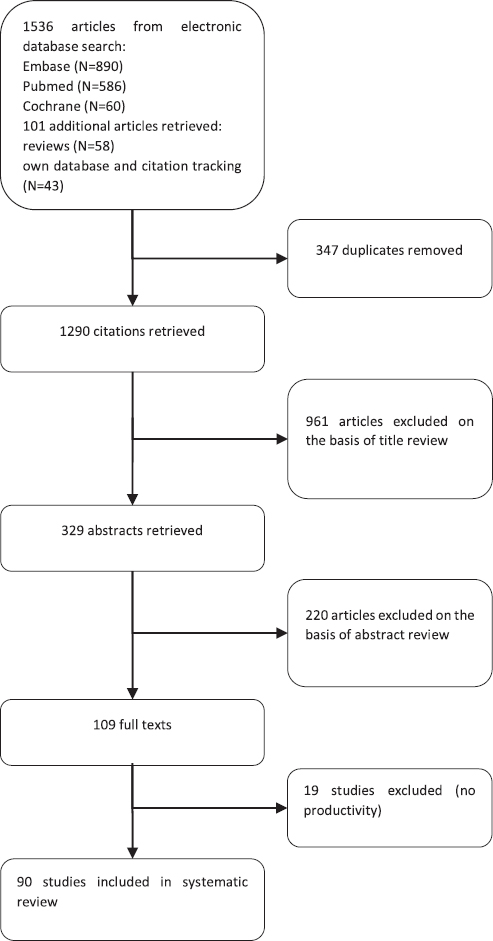

The study selection process and outcome is set out in figure 1. We conducted systematic searches in Embase, PubMed, NHS EED, DARE and Cochrane Library from 2007 up to 2017. Search terms included controlled vocabulary (MeSH and Emtree) and free-text terms, and consisted of three sets: related to economic evaluation, workplace settings or occupational interventions, and productivity (see appendix, table S1, www.sjweh.fi/show_abstract.php?abstract_id=3715). Additional articles were identified from reviews (12, 27–37), reference screening, and the authors’ own database.

Studies were included based on four criteria: the analysis (i) was a full or partial economic evaluation; (ii) included OHS interventions targeted at an employed (or return-to-work) population; (iii) included productivity in paid work; and (iv) was written in English, French, or Dutch. Studies were included if they concerned an intervention on health or safety at work, regardless of whether these interventions considered primary, secondary, or tertiary prevention.

After study selection, a data extraction form was created based on previous literature (3, 12, 13, 17, 38), to appraise the studies included in the review. A first set of measures describes general study characteristics: study method, type of economic analysis (following) (3), perspective, country of the study, sector, study design, and intervention details. Studies were then assessed on how productivity was estimated (the methodological approach), whether they included absenteeism and presenteeism, and how this was measured (objectively or through surveys, what instrument and its characteristics, and data sources). The method to measure presenteeism was also indicated: perceived impairment (asking employees how much their illness hindered them in performing tasks), comparative productivity (versus other colleagues or usual performance, often using Likert scales), and directly asking employees to estimate unproductive time at work (9, 17). When applicable, the valuation/monetization methods of lost time were analyzed, as well as their characteristics: price weights, friction period length used and source for this friction period estimate, and the use of the elasticity of labor to output. Finally, studies were assessed whether they controlled lost output for compensation mechanisms, used multipliers, or included additional costs (such as the costs of compensation mechanisms).

Results

Study background

Study characteristics of the 90 included studies (39–128) are represented in table 2, an extended table is available in the appendix table S2 (www.sjweh.fi/show_abstract.php?abstract_id=3715). Of these, 88 studies were written in English, with the remaining in French (57), and Dutch (68). Studies originated in Europe (56%), North America (38%), or other continents (7%), were performed in diverse sectors and industries, and studied a wide range of OHS intervention types. A substantial part (39%) of these economic evaluations was based on data from randomized controlled trials, and (18%) used uncontrolled before–after studies, of which some employed statistical analyses to control for confounders [eg, (47)], while others simply attributed all changes in outcomes to the intervention [eg, (103)]. Decision-analytic models were used in 14 studies (16%); other designs (28%) are detailed in the table. Cost-effectiveness analyses (CEA) were conducted in 71 studies (79%), 19 were cost-utility analyses (CUA) (21%), using QALY as outcome measure. Most of these CUA also included a CEA. Regarding primary perspective, 37 studies (41%) adopted a societal perspective, taking into account costs and effects that were not strictly relevant to the firm. Costs and effects relevant for the employer were the focus of 24 studies (27%), while 3 (3%) took a healthcare provider or insurance perspective. The other 26 studies (29%) did not explicitly mention a perspective, however, for all but 3 (102, 105, 113), it could be inferred based on the context. Analyses were repeated from an additional perspective in 23 studies (26%); 3 studies (3%) used three perspectives. Among the 90 selected studies, which all included some form of productivity estimation, 47 (52%) also included the intervention’s effect on health outcomes and 60 (67%) the effect on healthcare costs or worker’s compensation. In 20 studies (22%), neither health outcomes nor healthcare costs were included, making the overall impact of productivity estimation the major element of importance to the study, while 43 studies (48%) did not include an economic evaluation guideline – such as (3, 16, 19, 21, 129–133) in their methods.

Table 2

Characteristics of the included studies (N=90) and the interventions they studied. An extended table is available in an online annex. [BA=(uncontrolled) before–after study; CBA=controlled before–after study; CE=compensation expenses; CEA=cost-effectiveness analysis; CEA LT=cost-effectiveness analysis with lost-time in natural units (eg, cost per absence day avoided); CUA=cost-utility analysis; DAM=decision-analytic modelling; FCA=friction-cost approach; HCA=human-capital approach; HCT=historical controlled trial; PCS=prospective cohort study; RCS=retrospective cohort study; RCT=(cluster) randomized controlled trial]

Productivity estimation method

As summarized in table 2, 44 studies (49%) used the HCA, 17 (19%) the FCA, 13 studies (14%) stated productivity in natural units, 7 studies (8%) made use of compensation expenses, 4 studies (4%) estimated productivity changes by analyzing output or revenue data, and 1 study (1%) did not state its method. The remaining 4 studies (4%) all used ad hoc approaches that cannot be reduced to one of the above. For instance, Ektor-Andersen et al (58) valued lost time by using social security expenditures. Another study (40) made use of direct-to-indirect cost multipliers: direct costs of an intervention are gathered, after which a multiplier is applied to approximate the indirect productivity costs (or cost savings). However, note that the term “indirect costs” can also indicate additional effects (eg, reductions in informal care, home production, etc). No studies made use of the USP approach. In 18 studies, a second method was applied: most used either a HCA or compensation expenses. Less common were the addition of a (Pauly-Nicholson) multiplier approach, productivity in natural units, and an output-based method. Alamgir et al (40) combined three methods: a direct-to-indirect cost multiplier, stating productivity in natural units, and compensation expenses.

Measuring time loss

Only 5 (50, 55, 59, 76, 92) of the 90 studies did not include a measure of lost-time (absenteeism or presenteeism). This is because, in addition to studies with a primary or secondary method that used lost-time (productivity in natural units, HCA, or FCA), several of the ad hoc and output-based methods measured absenteeism or presenteeism. For instance, At’kov et al (42) measured absenteeism and presenteeism and valued it with an estimate of the contribution of the employee to firm profits (the marginal revenue of labor), and Ektor-Andersen et al (58) valued lost time using social security expenditures.

Absenteeism

As indicated in table 3, a measure for absenteeism (sick leave, disability leave or other health-related time away from work) was included in 83 studies (92%), 3 of which combined two measurement methods (39, 57, 60). Of these 83 studies (or 86 measurements), 26 (31%) made use of firm data, 26 (31%) of employee surveys, 10 (12%) used information from previous studies, 9 (11%) insurance data, 3 (4%) simulated or assumed absenteeism, 3 (4%) used data from the healthcare provider, 3 (4%) from national databases, and 1 (1%) each used data from a private research company, compensation data, and an employer survey. Among the 27 absenteeism surveys, a majority (44%) were self-constructed questionnaires, 19% did not state which instrument was used, 11% used the PROductivity and DISease Questionnaire (PRODISQ) although one adapted it, 7% used the Short-Form Health and Labour Questionnaire (SF-HLQ), 7% the net-cost model questionnaire, and 4% each used the TNO survey for cancer and work, the WHO-Health and Productivity Questionnaire (WHO-HPQ), and a cost diary. The recall periods of these instruments ranged from 24 hours (104) up to 6 months (87).

Table 3

Inclusion and measurement details of absenteeism, presenteeism, and friction periods by the studies included in this article (N=90). [PRODISQ=PROductivity and DISease Questionnaire; SF-HLQ=Short-Form Health and Labour Questionnaire; TiC-P=Trimbos/ iMTA questionnaire for Costs associated with Psychiatric Illness; QQ=Quantity and Quality questionnaire; WHO-HPQ=WHO-Health and Productivity Questionnaire]

The FCA was applied in 17 studies. This requires, in addition to observing days of absenteeism, an estimation of a friction period: the time it requires to replace an employee. A period of 154 days was used in 7 studies (41%), 4 (24%) used 23 weeks (roughly 161 days), 4 studies (24%) did not specify, 1 study (6%) used 92.68 days, and 1 (6%) 10 weeks (roughly 70 days). When a source was stated, it referred to the Koopmanschap et al seminal study (16) and/or the Dutch Costing Manual (130, 131), or the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (134). However, one of these studies (64) stated the source (16) but not the friction period length. Finally, Noben et al (88) estimated their own friction period using data on job vacancies.

Presenteeism

This was not taken into account in 59 studies (66%). Nonetheless, research indicates that both absenteeism and presenteeism are important factors: presenteeism can play a larger role than absenteeism in some diseases and for jobs that are physically and cognitively demanding, whereas absenteeism plays a larger role for jobs with high physical job demands (2, 135, 136). A measure for reduced performance at work was included in 31 studies (34%), 2 studies used two measures (44, 115). Employee surveys were used in 18 studies (58%), 7 studies (23%) simulated presenteeism or assumed that productivity under presenteeism was decreased by a certain percentage based on the literature [eg, a 50% (114) or a 25% (124) decrease in productivity], 6 studies (19%) used information from previous studies, and 1 study (3%) each used firm data or an employee survey. Of the 19 surveys, 10 studies (53%) used the WHO-HPQ, of which Osilla (94) used only part, 2 studies (11%) used PRODISQ, and 1 study (5%) each used the Trimbos/ iMTA questionnaire for Costs associated with Psychiatric Illness (TiC-P), the SF-HLQ in TiC-P, the Quantity and Quality (QQ) questionnaire, and the net-cost model questionnaire (in the employer survey). The remainder used self-constructed surveys (11%) or did not state which survey was used (5%). The range of recall periods for presenteeism instruments was similar to those of absenteeism above.

Regarding the method to estimate presenteeism within these surveys, 10 studies (53%) (those using the WHO-HPQ) used a combination of perceived impairment – by measuring self-assessed Likert scale reduced work performance due to sickness – and the comparative approach – by comparing global presenteeism estimates with those of a colleague (17). No approach was stated in 4 studies (21%), while 3 (16%) used a direct approach, asking for “extra hours needed to catch up on tasks unable to complete in normal working hours” (41, 64) or the number of days with decreased efficiency at work (104). The perceived change approach was used in 2 studies (11%) that asked employees to give their productivity a 0–1 inefficiency score (87, 89).

Data quality

Despite their frequent inclusion (83 of 90 studies), several studies reported having difficulties in obtaining good quality absence data (44, 45, 47, 53, 56, 57, 75, 91, 96, 97, 101, 105, 107, 116, 126). Often, data was confounded (eg, by other cause sick leave or holiday leave), or included only part of the relevant absences (eg, only compensated leave). In addition, the time unit of absenteeism and presenteeism measurements influenced the precision of the estimate. Of the 85 studies measuring lost-time, 49 (58%) used unspecified days (no mention of differentiation between partial and full sick leave days), 27 (32%) used hours, 3 (4%) used weeks, and 2 (2%) did not state a time unit. Other approaches were applied in 7 studies (8%): explicitly count part-time absenteeism as full-time absent days (45), use only full days of absence (56), use both gross (total number of calendar days – partial or full – absent) and net (partial absent days) sick leave (70, 100, 103); and use short-term absences of 4–9 days (57), or absence spells >4 weeks (105). A second time unit was used in 4 studies, thereby combining measurements in hours and days (64, 102, 114, 121).

Valuing time loss

A price weight to monetize lost-time measurements was used in 69 studies (77%). The other 21 studies (23%) (40, 46, 49–51, 54, 55, 59, 71, 76, 86, 91, 92, 98, 104–106, 110, 111, 113, 125) did not make use of (separate) price weights for monetization because they stated productivity outcomes in natural units, made direct use of compensation expenses, or used an ad hoc approach or output-based method.

Composition

Table 4 indicates that in about half of the 69 studies that used price weights (45%), these were composed of wages and secondary benefits. A third (32%) used wages only, 4 studies (6%) used compensation expenses (without wage) as the price weight, while 8 (12%) used alternative price weights. One of these used the labor cost and individual operating income per employee (42) and another the replacement cost of a worker (115). Others adjusted wages only for taxes (90) or used a multiplier for non-wage benefits (94). Finally, 2 studies (52, 53) used disability benefits divided by wage, while Ektor-Anderson et al (58) used social security expenditures and Kärrholm and colleagues (75) applied income qualifying for sickness benefit, adjusted for payroll taxes.

Table 4

Main results on the composition, type and source of price weights, and inclusion of an elasticity of labor to output, for studies that included a valuation of lost time (N=69).

Type

Regarding the price weight type, 19 studies (28%) used job averages and 18 (26%) applied national averages adjusted for age and gender (recommended by the Dutch costing manual). A generic national or regional price weight was used in 13 studies (19%), 9 (13%) used a worker-specific weight, 3 (4%) the industry or company average, and 1 (1%) a job average with age differentiation. Variations – such as using the mean annual salary per staff member in the NHSL (47), the study group average (75, 100), or the national average for blue- and white-collar workers (90) – were applied in 4 other studies (6%), while 3 used a second type of price weight: the national age and gender-specific average (100, 123) and a generic national weight (66).

Source

Data on the price weight was most often taken from previous studies (38%), company administration (17%), national databases (13%), employee self-reports (12%) or insurance data (7%).

Elasticity

The FCA recommends adjusting calculations for the “elasticity of labor”, ie, the less than proportional change in output per unit of labor. In total, 15 studies incorporated an elasticity factor; 14 used a value of 0.8 and 1 used several values: 0.3, 0.55, 0.8. Interestingly, 4 of the 14 studies did not follow the FCA but did include an elasticity factor (45, 66, 81, 83). The source for these elasticity values was Koopmanschap et al (16) and/or the Dutch Costing Manual (130, 131), except for Bernaards et al (45), who used the Netherlands economic institute as a source.

Additional costs and adjustments

Productivity costs of sick employees can also involve additional costs related to compensation mechanisms (eg, costs of replacement workers) or employee turnover. One author included overtime, staffing agency costs, and wages for temporary employees (125), while 4 studies included hiring costs (103, 106, 108, 115), such as equating the cost of lost time to the cost of a replacement worker (103, 115), including the cost of advertising and recruiting the replacement (108), or adding temporary and permanent replacement workers’ costs (106). The latter was also the only study to include the training costs of replacement workers. Employee turnover rates were included in 6 analyses (44, 59, 67, 76, 82, 88) with the view that improving the working environment or avoiding injuries, disabilities and diseases causes less employees to leave the firm (26). For instance, Barbosa et al (44) approximated “voluntary termination costs” through workers’ compensation and Lahiri and colleagues (76) included the cost of employee turnover rates by multiplying the change in personnel (by a headcount) by estimated costs of turnover by the company (expressed as a percentage of the job-category wage).

Finally, some studies separately adjusted the value of lost output for a compensation mechanism (apart from their productivity estimation method) or followed the Pauly-Nicholson approach (22) to reflect the fact that absenteeism costs might be higher than the wage. The latter was done in 2 studies (82, 94) by including job-multipliers, while 7 (8%) included a separate measure for compensation mechanisms to reflect that these can reduce output losses. Evanoff & Kymes (59) adjusted productivity losses to (all) replacement workers, At’kov et al (42) to internal replacements, and Palumbo et al (96) took only 75% of absences into account to reflect the fact that some production losses are compensated.

Uncertainty and discounting

Because of the large uncertainties involved, it is necessary to subject productivity estimations to a sensitivity analysis to see how results change – for instance by relaxing assumptions (eg, on the percentage used for presenteeism), by using alternative data sources, by including and excluding presenteeism, etc. As indicated in table 5, this was done in 61 studies (68%), while 21 (23%) stated to have discounted productivity estimates, and 53 (59%) mentioned inflation adjustments. Discounting and inflation adjustment is advised if the study length is more than a year.

Table 5

Main results on sensitivity analyses, discounting, and inflation of productivity loss by the included studies (N=90).

Discussion

In the past, some have advocated the view that quick and simple decision-making tools should be sufficient to convince employers of the benefits of occupational health and safety interventions (25). Whereas this may be practical and responsive to the immediate information needs of managers in a particular context, from a broader perspective there are good reasons to adhere to stronger scientific standards. First, even within a specific context, managers can implement many OHS programs and need to set priorities. If productivity estimations are insufficiently precise, they can lead to a sub-optimal allocation of available OHS resources, and thus to forgone benefits from other and “better” OHS programs. Second, economic evaluation of OHS programs is not only needed to convince local managers and decision makers, but it is also important to provide an evidence-base for discussions between governments, employers and trade unions. It can help to set out policy priorities within OHS, or facilitate comparisons with broader forms of healthcare and public health (eg, maximizing population health on a cost-per-QALY basis). When cost and effects for different parties are reported separately, it can even help to divide the burdens and benefits of OHS programs, and align incentives for OHS investments by means of subsidies or taxation (137–139).

Previous reviews of economic evaluation studies of OHS laid bare substantial methodological shortcomings in their approach to quantifying productivity change: a misplaced reliance on workers’ compensation expenses, a large group of studies that did not include presenteeism (13, 35, 36, 140–144), weak(er) study designs, and strong assumptions without controlling for these (20). The authors urged for more precision and standardization in future studies. This systematic review assessed the economic evaluations of OHS published in the preceding decade. In analyzing 90 studies, the overall results sketched a largely similar picture: a large heterogeneity in productivity measurement and valuation/monetization methods, big differences in the precision of the implementation of each method, limited comparability across studies, non-transparent reporting of methods used, exclusion of relevant cost-dimensions related to absenteeism and presenteeism, and limited sensitivity analysis and accounting for the uncertainty embodied in the presented estimates. The approach used seems to be based more on data availability and practical considerations than on scientific reflection of what constitutes the most valid and reliable method in a certain context. For instance, both compensation mechanisms and wage multipliers have been empirically demonstrated to matter (13, 15, 23), but were rarely included. More particularly, improvements are possible through increasing data quality or precision (eg, a lower reliance on compensation or undifferentiated sick leave data confounded with holiday leave), adding essential productivity components (such as presenteeism or replacement and turnover costs), reducing strong assumptions (eg, about presenteeism) or testing their impact, shortening the recall periods used in surveys, and more adequate adjustment for inflation or discounting. In addition, studies using the HCA could additionally calculate productivity costs through the FCA, since – especially in the case of absences longer than the friction period – the HCA might reflect only the “potential” costs, and overestimate the “actual” losses (14). To make this possible, estimates for friction periods should be made in other countries since up to now they have only been calculated for the Netherlands and the UK (16, 145). Not all these quality improvements of productivity estimation require additional time, data or resource investments: detailed reporting, adjustments to inflation or discounting, relaxing assumptions in sensitivity analyses, making use of job-specific wage multipliers, or using (a range of) elasticity values as proposed by Koopmanschap et al can all greatly increase the quality of cost-effectiveness research in OHS, and could easily be added (eg, in sensitivity analyses next to the main analysis).

All this adds evidence to the observation of previous authors that there is, as of yet, no consensus on the specifics of the measurement and valuation/monetization method of productivity (2, 5, 10, 12, 18, 21, 22, 132, 146). Guidelines should be developed, keeping in mind cross-countries differences, for instance in worker’s legislation and compensation regulation (12). Many Dutch studies seem already committed to increased standardization and used the Dutch Costing Manual to their advantage (17, 130, 131). Given the close relations between OHS and the firm, this field might prove an ideal setting to advance the broader field of economic evaluation. First, the closer ties with companies in OHS may render objective measures for productivity changes more feasible. Even if only a few employers can be convinced to engage in a study, this can give many opportunities to validate measurement instruments objectively, compare productivity methods against an output-based standard, or further advance research of compensation mechanisms and multipliers. Several authors have noted that the general quality and relevance of economic evaluation in the OHS field falls below the standard in other domains of healthcare (7, 20, 147). The OHS community should not fall behind in incorporating state-of-the-art methods into economic evaluations and can even take a lead position experimenting with methods to assess how productivity should be measured.