The International Labour Organization (ILO) and the World Health Organization (WHO) have called on member countries to strengthen occupational health services (OHS) to better respond to the needs of health and work ability of their working populations (1–5).

The purpose of the present study was to survey International Commission on Occupational Health (ICOH) member countries on the current status of national OHS systems in view of the objectives and standards set by the aforementioned international organizations.

Methods

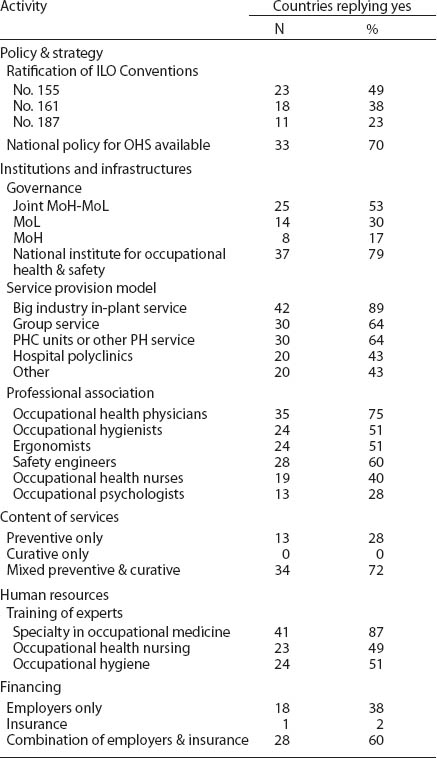

A questionnaire of 20 questions was developed by utilizing the previous occupational health surveys (6–8) for various target groups in OHS. The questions covered six main domains covering (i) normative basis; (ii) OHS system and infrastructures; (iii) substantive orientation and content of OHS; (iv) human resources for OHS; (v) finances for OHS; and (vi) future priorities for development of the national OHS system (tables 1 and 2).

Table 1

Responses to survey questions [MoH=Ministry of Health; MoL=Ministry of Labor; PH=public health; PHC=primary health care].

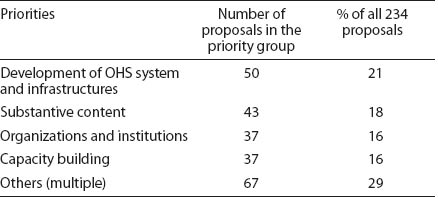

Table 2

Responses to survey questions concerning future priorities for development of occupational health services (OHS).

The survey covered 61 ICOH national secretaries with good information on occupational health in their respective countries. Replies were obtained from 47 countries worldwide. Of those who responded, 80% were affiliated with well-established national organizations, national institutes of occupational health, universities, ministries, or national associations of occupational health. The remaining 20% came from various sectors of work life.

Results

Representativeness of the study

The overall response rate was satisfactory (77% out of 61 countries). The respondent countries have a total of 2.1 billion economically active workers, approximately two-thirds of the total global labor force (4). The highest response rates (75–100%) were recorded from industrialized countries, but also the rates for developing countries (eg, from Africa) were good (over 60%).

Policy and strategy

In line with the ILO recommendation, 70% of respondents have an OHS policy adopted in most cases at the highest political level (table 1). The majority of the respondent countries stipulate, through law, the obligation of employers to organize OHS to the workers. In some countries, the public sector is responsible for OHS provision.

Institutions and infrastructures

In 37 countries (79% of respondents), the lead development institution for OHS is the national institute of occupational health, institute of occupational health and safety, government authority, or university department (table 1). In some countries (eg, Croatia), the responsibility is shared among several institutions.

Content of services

In 34 respondent countries (72%), the OHS provided both preventive and curative services, and in 13 countries (28%) preventive services only. The multidisciplinary content of services was common; over 85% of respondents reported a total of 10 different activities for OHS, including surveillance of work environment and workers’ health, risk assessment, health education and information, diagnosis of occupational diseases, and prevention of accidents. The provision of such content requires multidisciplinary OHS staff; 94% of respondents use ≥3 expert categories in OHS.

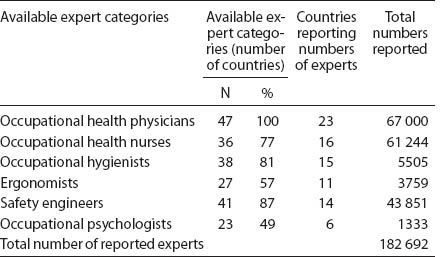

Human resources

Qualitative information on the availability of various expert categories was obtained from most of the responding countries, but only less than half were able to provide numbers in various expert categories (tables 1 and 3).

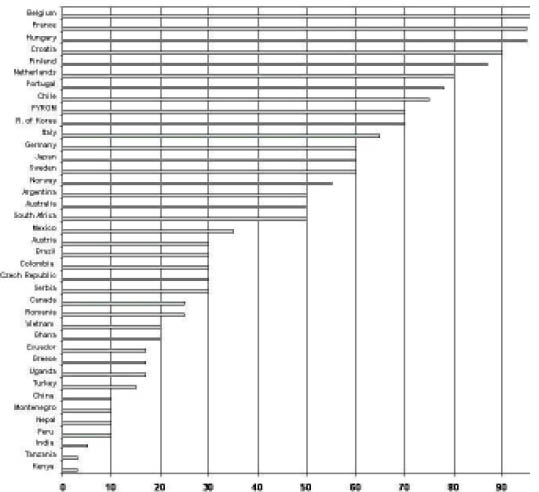

Coverage

Coverage of OHS as a percentage of the total employed population with services varied widely between 3–97%. More than half of the workforce was covered in 15 countries (38% of the 39 respondents) (figure 1). Low coverage figures were found in developing countries and large emerging economies. OHS serve approximately 346 million workers in the 39 countries, which provided coverage data, giving an average coverage of 19% of their total employed population of 1.8 billion. With only a few exceptions, the coverage is insufficient and the gap is seen particularly in small enterprises, among the self-employed, and in agriculture and the informal sector. On average, 81% of the total working population in the surveyed countries do not have access to services; the respective global estimate is 85–90% (10).

Financing

In 62% of respondent countries “combined financing” (employer and insurance) was applied; in 38% the “employer-only” model was used (table 1). Thailand finances Basic Occupational Health Services (BOHS) from public sources, Croatia has a specific insurance for OHS, and Finland reimburses 50–60% of costs of OHS from social insurance to the employer.

Future priorities for development of OHS

A total of 44 countries (97%) identified 234 priority development items (table 2): (i) OHS systems (50 items); (ii) substantive content (43); (iii) organizations and institutions (37); (iv) capacity building (37); (v) information systems (20); (vi) legislation (19); (vii) research (19); (viii) financing systems (6); and (ix) others (3).

Discussion

Key informant surveys have been widely used in research of health service systems (11). The feasibility of ICOH national secretaries as key informants on OHS in their countries was good. The response rate was reasonable (77%), and respondents represent roughly 90% of the total ICOH membership, employing 66% of the world’s total workforce. More accurate quantitative information needs development of national information and statistics systems on OHS.

The replies indicate that the use of ILO instruments as policy guidance is wider than ratification only. Most of the countries, however, have failed in the system-wide implementation of strategies, programs, and international and national instruments (“implementation gap”). In spite of the available national policies and programs, the majority of the workers do not have access to OHS in two-thirds of the respondent countries.

National institutes of occupational health or safety were available in the majority (79%) of the countries, but services at the workplace level were less developed. The “coverage gap” was most common in the high-risk sectors, such as small enterprises and agriculture.

There is a shortage of occupational health experts in the world of work (“capacity gap”). To achieve a global density of OHP for the total economically active population [equalling the density calculated for a sample of employed population in 23 countries (with adequate data on numbers of experts) in this survey (1/8155)] would need 312 800 more OHP. International organizations have proposed the BOHS and primary health care approaches as solutions to reduce the gap, and there are experiments ongoing in several countries (12–17).

According to the ILO guidance, the OHS should provide surveillance of the work environment and workers’ health, risk assessment, prevention of occupational injuries and diseases, first aid, curative care, maintenance of work ability, health promotion and education, and workplace development services (ie, comprehensive OHS). The absolute numbers of various expert categories, however, are so limited that the multidisciplinary services are possible only in a few countries. Thus the “content gap” is prevalent.

The combined financing and the employer-only models fit well to the organized sectors of work life. Most of the workers in the coverage gap are employed in less organized settings with high risks, often without any social protection and insurance, and a formal employment contract. Organizing funding for such sectors needs public interventions either through direct government action or through public social insurance.

The low coverage of OHS is often explained by limited financial resources and in interest to ensure economic competitiveness. The financial loss resulting from occupational accidents and diseases, however, is estimated to be 4–5.9% of GDP (18–19), corresponding to about half of the total health budgets of the countries. The World Economic Forum competitiveness index (20) correlates well with the OHS coverage (r=0.52723, t=3.7228, P<0.001), thus suggesting that the growing coverage does not negatively affect the competitiveness of the countries.

The priorities for future developments aligned well with the identified needs (eg, strengthening of prerequisites, infrastructures, capacities, and content of OHS). There is a greater need for the implementation of the international instruments, national policies, strategies, laws and programs rather than the generation of new instruments. This may reflect the identification of the existing gaps among the responding countries.