Globally, mental illness is a key contributor to disability burden (1). In an effort to reduce the prevalence of mental illness, risk factor identification (and prevention) in the workplace has become a major focus of research as well as both government and employment policy (2). Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have consistently found that psychologically stressful employment conditions (including jobs with high demands, low control/autonomy, insecurity, and poor social support) are associated with poorer mental health (3–6). This research field is primarily influenced by Karasek’s job demands–control model (7). The model posits that job strain, a state produced by the combination of high job demands and low job control, places employees at an increased risk of health problems. Following on from the job strain model, much of the literature investigating psychosocial job conditions and mental health has focused on combined (rather than single) indicators of psychosocial stress at work. For example, multiple longitudinal studies have shown that high job strain (high demands and low control) precedes declines in mental health (8–12) as do increases in the number of adverse psychosocial job conditions experienced (eg, combined experiences of high job demands, low job control, job insecurity) (13, 14).

Research has also examined the individual indicators of poor psychosocial job quality and, in the case of most indicators including low job control, has reliably shown an association with poorer mental health. For example, a UK study by Stansfeld et al (15) showed an increased risk of psychiatric disorders among those with low decision authority. Bentley et al (16) and Butterworth et al (17) analyzed seven or more waves of Australian panel data and showed that mental health improved with increases in job control over time. A recent UK longitudinal study by Harvey et al (12) found that low job control predicted higher odds of subsequent common mental disorder. While there is a substantial body of research linking low job control with poorer mental health, the possibility of residual confounding remains a major barrier to causal interpretations in longitudinal research (12). There are many non-work related mental health risk factors that may be associated with self-reported job control, including psychological resources and personality characteristics. While research by Stansfeld et al (15) and Harvey et al (12) did control for some aspects of personality (eg, adult hostility and adolescent temperament respectively), very little research has considered the role that perceptions of control more broadly (ie, not isolated to the work context) might play. Measures of control in the workplace may simply be a proxy for perceptions of control more generally, or alternatively, it may be that control in the workplace is associated with mental health independent of non-work influences. One relevant study by Clark et al (18) used cross-sectional data from the 2007 UK Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey to investigate the contribution of both work and non-work stressors to common mental disorders. The findings suggest that the effects of work stressors are not explained by broader non-work stressors such as adverse life events (eg, financial strain, separation/divorce, domestic violence), caring responsibilities, and low social support. However, this research only used data from a single point in time and did not specifically investigate the contribution of control within and outside the workplace.

The current study aims to fill this knowledge gap by using four waves of Australian community-based data to examine the association between job control (one of the main components in Karasek’s job demands–control model) and common mental disorder, independent of a broader sense of control in life. It is important to account for the influence of control more broadly, as without doing so, the effect of job control might simply reflect perceptions of low control over life circumstances more generally rather than being specific to work. This study separated within- and between-person differences in both job control and broader sense of control to show how time-varying change in job control is associated with change in mental health, adjusted for other residual confounders (eg, between-person differences in job control as well as within- and between-person broader sense of control). The findings are reported according to the STROBE statement for cohort studies (19).

Methods

Participants

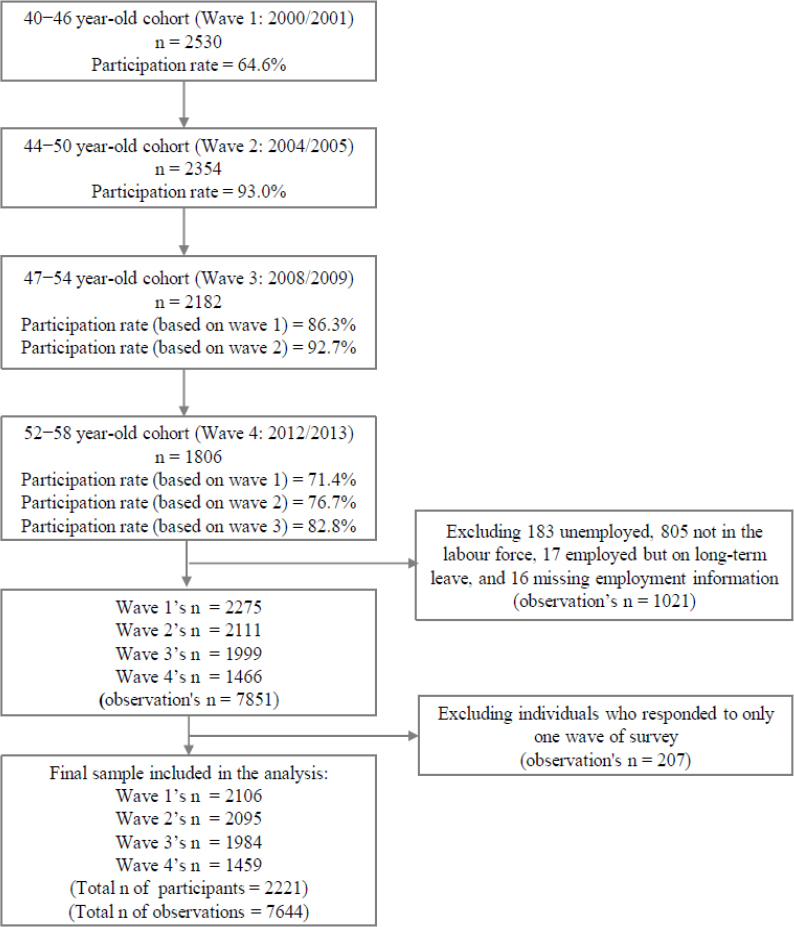

Participants were from the Personality and Total Health (PATH) Through Life Project, a large longitudinal community survey on individual health and well-being trajectories across the life course. The survey was undertaken by the Centre for Research on Ageing, Health and Wellbeing at the Australian National University (ANU). The sample comprises cohorts of young, midlife, and older adults randomly selected from the Australian Electoral Rolls of Australian Capital Territory and the neighboring town of Queanbeyan (20). The current study was restricted to the midlife cohort who were aged 40–44 years at baseline, and subsequently assessed every (approximately) four years from 2000/2001 (wave 1) to 2012/2013 (wave 4). The participation rate of this cohort at baseline was 65% (2530 participants), where 93% of baseline participants completed the survey at wave 2, 86% at wave 3, and 71% at wave 4 (figure 1). For the first three waves, participants were typically assessed in their own home or at the ANU. They were invited to complete a questionnaire using a laptop computer under the supervision of a trained interviewer. For the fourth wave, participants were invited to complete an online version of the questionnaire and those in the local area were invited to undertake additional face-to-face assessment. All participants provided informed consent to participate at each wave of the study, and each wave of data collection was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Australian National University.

The current study excluded observations from participants when they (i) were not employed (ie, unemployed or not active in the labor force); (ii) were employed but on long-term leave; or (iii) did not provide information on their status of employment (figure 1). Given the longitudinal focus, participants with fewer than two waves of data were also excluded.

Measures

Common mental disorder. Anxiety and depression were assessed using the Goldberg Anxiety and Depression scales (21) at all four waves. Each scale comprises nine binary items (yes or no) about anxiety or depressive symptoms experienced in the past month. The total score for each measure was computed by summing the number of “yes” responses and dichotomized using the established cut-off points indicative of symptoms of anxiety or depressive disorders (22). A binary measure of common mental disorder was then generated based on the presence of depressive and/or anxiety symptoms. A continuous measure of common mental disorder severity was also calculated based on number of symptoms of anxiety and depression experienced (ranging from 0–18) – this measure was adopted in sensitivity analyses.

Control at work. At all four waves, 15 items from the Whitehall II study (23) assessed aspects of job control (eg, skill discretion: “Do you have a choice in deciding how you do your job?”; decision authority: “Does your job provide you with a variety of interesting things?”). These items offered four response categories: 1=often, 2=sometimes, 3=rarely, and 4=never. Aligned with the methodology used in previous studies (17, 24), a score for job control was calculated by combining the average scores for skill discretion and decision authority and then divided into tertiles identifying three groups representing high, medium, and low job control. This approach was similarly used in the Whitehall II study (15). In addition to the time-varying measure of job control, a between-person (ie, time-invariant) measure was computed to identify respondents who experienced low job control at some point over the four waves. This measure was used as indicator of individual susceptibility or vulnerability to experience adverse job conditions.

General perceptions of control

General perceptions of control assessed by the Pearlin Mastery Scale (25), which was included in all waves. Perceived mastery is a psychological resource that has been defined as “the extent to which one regards one’s life-chances as being under one’s own control in contrast to being fatalistically ruled” (25). The items (eg, “There is really no way I can solve some of the problems I have” and “I have little control over the things that happen to me.”) offered four response categories: 1=strongly agree, 2=agree, 3=disagree, and 4=strongly disagree. The seven items were summed and the total score categorized into tertiles, representing high, medium, and low general control. The analyses also included a between-person (ie, time-invariant) measure of general control, derived by calculating respondents average mastery scale score over the survey waves.

Other covariates

Work-related. Four items from the Whitehall II study (23) assessing aspects of job demands (eg, “Do you have to work very intensively”) with four response categories (1=often, 2=sometimes, 3=rarely, and 4=never) were included from all waves. As with job control, we computed the average score for this measure and then used tertiles to identify three groups representing high, medium, and low job demands. One item: “How secure do you feel about your job or career future in your current workplace?” with four response categories (“not at all secure”, “moderately secure”, “secure”, “extremely secure”) was used to assess job insecurity. The former two categories were coded as high insecurity and the latter two as low insecurity.

Sociodemographic and health covariates. We included other variables that may potentially confound the association between job control and common mental disorders (26–28): time-invariant measures from baseline (ie, gender, educational attainment) and time-varying measures from each wave (ie, partner status, occupational skill level, parental responsibilities, childhood adversity, financial hardship, chronic physical health conditions, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and physical exercise).

Seventeen items on childhood adversity were adopted and adapted from the Parental Bonding Instrument (29), the British National Survey of Health and Development (30), the US National Comorbidity Survey (31), and from open-ended responses in a previous cross-sectional study (32). These items comprised six covering parental affection, parental nervous/emotional trouble, and parental drinking/drug problems; two covering conflict in the household and parental divorce/separation; eight covering neglect, authoritarian upbringing, witnessing physical/sexual abuse, as well as verbal abuse, psychological abuse, physical abuse, physical punishment, and sexual abuse by a parent; and one item covering childhood poverty/financial hardship. Participants were categorized as having childhood adversity if they responded yes to any of these items. Current financial hardship was generated based on one item: “Have you or your family had to go without things you really needed in the last year because you were short of money?” Respondents were classified as having financial hardship if they responded yes, often or yes, sometimes to this item.

Chronic physical health conditions including heart problems, hypertension, cancer, arthritis, thyroid problems, epilepsy, asthma, diabetes, and stroke were considered and coded as a summary variable representing the experience of 0, 1, or ≥2 of these conditions. Hazardous/harmful alcohol consumption (33) was derived from the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (34) and classified as yes and no. The hours respondents engaged in moderate or vigorous physical exercise per week was assessed by items in the Whitehall II study (35) and categorized into five groups: 0, <1.5, 1.5−3, 3.1–5.5, and >5.5 hours. The categories of covariates not described in detail above are presented in table 1.

Table 1

Sample characteristics at baseline (N=2106).

| Overall | Low job control | Medium job control | High job control | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 1052 | 49.9 | 266 | 38.6 | 387 | 52.4 | 399 | 58.8 |

| Female | 1054 | 50.1 | 423 | 61.4 | 351 | 47.6 | 280 | 41.2 |

| Partner status | ||||||||

| No partner (separated/divorced/widowed/never married) | 414 | 19.7 | 154 | 22.4 | 153 | 20.7 | 107 | 15.8 |

| Having a partner (married/in a de facto relationship) | 1692 | 80.3 | 535 | 77.7 | 585 | 79.3 | 572 | 84.2 |

| Education completion | ||||||||

| Incomplete high school | 561 | 26.6 | 248 | 36.0 | 196 | 26.6 | 117 | 17.2 |

| Completion of high school | 695 | 33.0 | 257 | 37.3 | 243 | 32.9 | 195 | 28.7 |

| Completion of tertiary study | 850 | 40.4 | 184 | 26.7 | 299 | 40.5 | 367 | 54.1 |

| Occupational skill level a | ||||||||

| Low | 420 | 19.9 | 276 | 40.1 | 102 | 13.8 | 42 | 6.2 |

| Medium | 564 | 26.8 | 192 | 27.9 | 220 | 29.8 | 152 | 22.4 |

| High | 1122 | 53.3 | 221 | 32.1 | 416 | 56.4 | 485 | 71.4 |

| Parental responsibilities | ||||||||

| No (no youngest child aged <15 years) | 720 | 34.2 | 251 | 36.4 | 260 | 35.2 | 209 | 30.8 |

| Yes (youngest child aged <15 years) | 1386 | 65.8 | 438 | 63.6 | 478 | 64.8 | 470 | 69.2 |

| Childhood adversities | ||||||||

| No | 810 | 38.5 | 233 | 33.8 | 290 | 39.3 | 287 | 42.3 |

| Yes | 1283 | 60.9 | 450 | 65.3 | 444 | 60.2 | 389 | 57.3 |

| Unknown | 13 | 0.6 | 6 | 0.9 | 4 | 0.5 | 3 | 0.4 |

| Financial hardship | ||||||||

| No | 1695 | 80.5 | 513 | 74.5 | 608 | 82.4 | 574 | 84.5 |

| Yes | 380 | 18.0 | 167 | 24.2 | 121 | 16.4 | 92 | 13.6 |

| Unknown | 31 | 1.5 | 9 | 1.3 | 9 | 1.2 | 13 | 1.9 |

| Number of chronic physical health conditions | ||||||||

| 0 | 1195 | 56.7 | 393 | 57.0 | 401 | 54.3 | 401 | 59.1 |

| 1 | 704 | 33.4 | 225 | 32.7 | 268 | 36.3 | 211 | 31.1 |

| ≥2 | 207 | 9.8 | 71 | 10.3 | 69 | 9.4 | 67 | 9.9 |

| Smoking status | ||||||||

| Never/past smoker | 1729 | 82.1 | 544 | 79.0 | 607 | 82.3 | 578 | 85.1 |

| Current smoker | 377 | 17.9 | 145 | 21.0 | 131 | 17.8 | 101 | 14.9 |

| Hazardous/harmful alcohol consumption | ||||||||

| No | 1978 | 93.9 | 656 | 95.2 | 693 | 93.9 | 629 | 92.6 |

| Yes | 128 | 6.1 | 33 | 4.8 | 45 | 6.1 | 50 | 7.4 |

| Moderate/vigorous physical exercise (hours in the last week) b | ||||||||

| 0 | 406 | 19.3 | 165 | 24.0 | 138 | 18.7 | 103 | 15.2 |

| <1.5 | 444 | 21.1 | 163 | 23.7 | 150 | 20.3 | 131 | 19.3 |

| 1.5−3.0 | 357 | 17.0 | 115 | 16.7 | 117 | 15.9 | 125 | 18.4 |

| 3.1−5.5 | 514 | 24.4 | 139 | 20.2 | 197 | 26.7 | 178 | 26.2 |

| >5.5 | 385 | 18.3 | 107 | 15.5 | 136 | 18.4 | 142 | 20.9 |

| General control (ie, mastery) | ||||||||

| Low | 420 | 19.9 | 214 | 31.1 | 136 | 18.4 | 70 | 10.3 |

| Medium | 946 | 44.9 | 343 | 49.8 | 353 | 47.8 | 250 | 36.8 |

| High | 726 | 34.5 | 126 | 18.3 | 245 | 33.2 | 355 | 52.3 |

| Unknown | 14 | 0.7 | 6 | 0.9 | 4 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.6 |

a Low occupational skill level included intermediate production and transport workers; elementary clerical, sales and service workers; and laborers and related workers. Medium occupational skill level included associate professionals; tradespersons and related workers; and advanced clerical and service workers. High occupational skill level included managers and administrators; and professionals.

Statistical analyses

Sample characteristics at baseline and descriptive information for job control and common mental disorder at each wave were reported. Chi-square test was used to assess the relationship between job control and general control. To appropriately model the lack of independence in the data, given repeated measures from the same individuals, longitudinal random-intercept logistic regression models with two levels (occasion clustered within individuals) were used to assess the association between job control and common mental disorder over time (36). These models also facilitate the use all available data (rather than restriction to complete case analysis), and permit the decomposition of time-varying covariates into elements representing within-person change over time and consistent between-person differences (36). The model fitted a fixed (average) regression slope for common mental disorder over time while permitting the intercept to vary between respondents to reflect differences between individuals in their likelihood of common mental disorder. The longitudinal models first included time-varying job control (model 1) and general control (model 2), followed by between-person terms for job control and general control (model 3), and finally other work-related covariates, sociodemographic, and health variables (model 4). Survey wave (a category term) was included in all models. We also assessed the association of each covariate with common mental disorder, adjusted for survey wave only.

In addition, we compared the model comprising only the main effects of job control and general control with a model that also incorporated the interaction term using the likelihood ratio test. We did the same test for job control and gender, and for general control and gender.

The proportion of observations with missing data on all variables was low, ranging from 0–1.5% (financial hardship was highest). All analyses were conducted using Stata Statistical Software: release 14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity tests included repeating the analyses (using negative binomial regression models) with a continuous outcome representing severity of common mental disorder to assess whether the results from these models differed from those obtained from the models with binary outcome of common mental disorder. Another sensitivity test repeated the analyses with a fixed-effect model rather than a random-effect model with between-person terms.

Results

The study included 2106 participants aged 40–44 at baseline (table 1, see descriptions of sample characteristics by level of job control in table 1 and by level of general control in table S4 in the supplementary material, www.sjweh.fi/show_abstract.php?abstract_id=3869). Of these participants, half were male, 20% did not have a partner, 27% did not complete high school, 20% were in low-skilled occupations, 66% had a youngest child aged <15 years, 61% experienced ≥1 adversity during childhood, and 18% were experiencing financial hardship. In terms of their health, 10% of participants had ≥2 chronic physical health conditions, 18% currently smoked, 6% consumed alcohol at hazardous/harmful levels, and 19% spent less than an hour doing moderate/vigorous physical exercise per week.

The chi-square test showed a significant relationship between job control and general control [X2(4, N=2092) = 205.38, P<0.001]. However, 17% of respondents who reported low job control also reported high general control. Similarly, 17% who reported high job control also reported low general control, suggesting these two measures were not collinear.

There was movement between low, medium, and high categories of job control and general control over the 12-year period (table 2). The proportion of respondents reporting low job control at any point in time (55%) was greater than the proportion at each wave (eg, 35% at wave 4). The proportion of respondents reporting low general control at any point in time (40%) was also greater than the proportion at each wave (eg, 23% at wave 4). There was also variability over time in common mental disorder. Around 42% of respondents reported symptom levels reflective of a common mental disorder at some point over the survey waves.

Table 2

Descriptive statistics on exposures and outcome at each wave.

| All waves (observations=7644) | 2000/2001 (persons=2106) | 2004/2005 (persons=2095) | 2008/2009 (persons=1984) | 2012/2013 (persons=1459) | Any wave a (persons=2221) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Job control | ||||||

| Low | 2475 (32.4) | 689 (32.7) | 657 (31.4) | 624 (31.5) | 505 (34.6) | 1221 (55.0) |

| Medium | 2581 (33.8) | 738 (35.0) | 696 (33.2) | 678 (34.2) | 469 (32.2) | 1460 (65.7) |

| High | 2563 (33.5) | 679 (32.2) | 738 (35.2) | 679 (34.2) | 467 (32.0) | 1197 (53.9) |

| Unknown | 25 (0.3) | 0 | 4 (0.2) | 3 (0.2) | 18 (1.2) | 25 (1.1) |

| General control (ie, mastery) | ||||||

| Low | 1584 (20.7) | 420 (19.9) | 450 (21.5) | 375 (18.9) | 339 (23.2) | 878 (39.5) |

| Medium | 3203 (41.9) | 946 (44.9) | 910 (43.4) | 734 (37.0) | 613 (42.0) | 1627 (73.3) |

| High | 2796 (36.6) | 726 (34.5) | 723 (34.5) | 864 (43.6) | 483 (33.1) | 1329 (59.8) |

| Unknown | 61 (0.8) | 14 (0.7) | 12 (0.6) | 11 (0.6) | 24 (1.6) | 59 (2.7) |

| Common mental disorder | ||||||

| No | 5884 (77.0) | 1563 (74.2) | 1639 (78.2) | 1541 (77.7) | 1141 (78.2) | 2043 (92.0) |

| Yes | 1720 (22.5) | 532 (25.3) | 447 (21.3) | 432 (21.8) | 309 (21.2) | 934 (42.1) |

| Unknown | 40 (0.5) | 11 (0.5) | 9 (0.4) | 11 (0.6) | 9 (0.6) | 38 (1.7) |

Job control and common mental disorder over time

Table 3 shows a series of models investigating the association between job control and likelihood of common mental disorder. Job control was significantly associated with common mental disorder in simple and adjusted models, although the magnitude of the effect was attenuated after controlling for general control. After adjusting for all covariates, including between-person differences in job control and general control, the results show that when individuals were in jobs with low control (ie, within-person change) they were at twice the risk of common mental disorder compared to when they held a job with high control (OR 2.04, 95% CI 1.53‒2.73). Other variables associated with greater risk of common mental disorder in the final model included current experiences of low general control (eg, within-person effect) and overall average perceptions of general control (eg, between-person effect), high job demands and job insecurity, being female, childhood adversity, financial hardship, having one or more chronic physical conditions, and smoking. Those who had a low skilled occupation appeared at lower risk (although this likely arose from over-adjustment in the final model given the opposite pattern was evident in the univariate analysis). In all models, there was a significant effect of time, suggesting that the odds of common mental disorders decreased after baseline. The interactions between job control and general control, between job control and gender, and between general control and gender were not significant.

Table 3

Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) from longitudinal random-intercept logistic regression models assessing the relationship between job control and common mental disorder

| Model 1 a | Model 2 b | Model 3 c | Model 4 d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Job control | ||||

| Low | 4.33 (3.41−5.51) e | 2.41 (1.90−3.07) e | 2.06 (1.56−2.72) e | 2.04 (1.53−2.73) e |

| Medium | 2.37 (1.9−2.96) e | 1.81 (1.45−2.26) e | 1.66 (1.32−2.09) e | 1.59 (1.26−2.00) e |

| High (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| General control (ie, mastery) | ||||

| Low | 19.36 (14.96−25.05) e | 15.8 (12.14−20.56) e | 6.06 (4.45−8.27) e | 5.94 (4.32−8.18) e |

| Medium | 3.38 (2.72−4.20) e | 3.00 (2.40−3.74) e | 1.82 (1.43−2.30) e | 1.84 (1.44−2.34) e |

| High (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Low control in any wave | 3.26 (2.53−4.20) e | 0.94 (0.70−1.25) | 0.87 (0.66−1.17) | |

| Mean of mastery across waves | 0.64 (0.61−0.66) e | 0.76 (0.72−0.80) e | 0.80 (0.76−0.84) e | |

| Job demands | ||||

| Low (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Medium | 1.31 (1.03−1.67) f | 1.39 (1.08−1.79) f | ||

| High | 2.33 (1.83−2.96) e | 2.38 (1.85−3.07) e | ||

| Job insecurity | ||||

| Low (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| High | 2.19 (1.82−2.63) e | 1.46 (1.20−1.77) e | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Female | 1.66 (1.29−2.13) e | 1.40 (1.10−1.77) g | ||

| Partner status | ||||

| No partner | 1.51 (1.19−1.92) g | 1.16 (0.91−1.47) | ||

| Having a partner (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Education completion | ||||

| Incomplete high school (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Completion of high school | 0.85 (0.62−1.16) | 0.92 (0.69−1.24) | ||

| Completion of tertiary study | 0.55 (0.41−0.76) e | 0.75 (0.54−1.03) | ||

| Occupational skill level | ||||

| Low | 1.32 (1.01−1.71) f | 0.73 (0.54−0.99) f | ||

| Medium | 1.41 (1.14−1.75) g | 1.12 (0.89−1.41) | ||

| High (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Parental responsibilities | ||||

| No (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 0.86 (0.70−1.05) | 0.95 (0.77−1.18) | ||

| Childhood adversities | ||||

| No (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 3.12 (2.39−4.07) e | 2.01 (1.58−2.55) e | ||

| Financial hardship | ||||

| No (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 3.11 (2.47−3.92) e | 1.89 (1.49−2.38) e | ||

| Number of chronic physical health conditions | ||||

| 0 (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 1 | 1.40 (1.15−1.71) g | 1.33 (1.09−1.63) g | ||

| ≥ 2 | 1.62 (1.25−2.12) e | 1.43 (1.09−1.86) g | ||

| Smoking status | ||||

| Never/past smoker (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Current smoker | 1.82 (1.38−2.40) e | 1.57 (1.20−2.06) g | ||

| Hazardous/harmful alcohol consumption | ||||

| No (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1.13 (0.80−1.58) | 1.09 (0.77−1.54) | ||

| Moderate/vigorous physical exercise | ||||

| 0 (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| <1.5 | 0.87 (0.67−1.12) | 1.00 (0.77−1.31) | ||

| 1.5−3.0 | 0.84 (0.64−1.11) | 1.05 (0.79−1.39) | ||

| 3.1−5.5 | 0.57 (0.44−0.75) e | 0.82 (0.62−1.07) | ||

| >5.5 | 0.54 (0.40−0.71) e | 0.78 (0.58−1.05) | ||

| Survey wave | ||||

| 1 (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 0.71 (0.59−0.86) e | 0.67 (0.55−0.81) e | 0.67 (0.55−0.81) e | 0.69 (0.56−0.85) e |

| 3 | 0.77 (0.63−0.93) g | 0.83 (0.68−1.01) | 0.80 (0.65−0.97) f | 0.82 (0.66−1.03) |

| 4 | 0.71 (0.57−0.88) g | 0.65 (0.52−0.81) e | 0.67 (0.54−0.83) e | 0.64 (0.49−0.84) g |

Results from the sensitivity analyses

In sensitivity analyses we observed a similar pattern of results with the count outcome as when a binary outcome was adopted. A model adjusting for all covariates showed that low job control was significantly associated with greater severity of common mental disorder [incidence rate ratio (IRR) for low versus high job control was 1.19, 95% CI 1.13‒1.25]. The same pattern of results was also found using a fixed-effect model (OR for low versus high job control was 2.23, 95% CI 1.59‒3.13).

Discussion

The current study analyzed four waves of community cohort data to examine whether the association between control at work and risk of common mental disorder is independent of general perceptions of control. The findings show that after adjusting for the adverse effect of low perceptions of control generally, being in a job with low control was independently associated with a two-fold risk of common mental disorder. This effect remained after adjusting for between-person differences in (or susceptibility to) low control both within the workplace and more generally, job demands, job insecurity, and sociodemographic and health confounders.

The current study supports previous research indicating that low job control is an important independent predictor of poor mental health. This finding extends existing knowledge from a variety of countries, including Australia (where improvement in job control has been associated with better mental health (16), and in the UK (12, 15). More importantly, the current study makes a unique contribution by showing that the mental health impact of low job control is not simply a measurement artefact, or a subset or reflection of perceptions of low control over life circumstances more broadly. In addition, the separation of within- and between-subject effects in the present study furthers efforts to distinguish the impact of low job control from other residual confounders, including those within and outside the workplace. Together with intervention studies that have shown the mental health benefits of increasing employee control (37), our findings indicate that good job control should be a target for workplace policy and practice. The findings negate concerns that work-based change will be ineffective if broader issues within the personal lives of employees are not addressed.

There are some limitations that should be considered in the interpretation of our findings. First, the sample was recruited from Canberra and Queanbeyan, in Australia. As Canberra is a city that includes many professionals and public servants, (baseline sample comprised of 53% professionals), the results may not be replicated in samples drawn from more disadvantaged communities, nor the broader Australian population. Second, as the study only included data from the path midlife cohort (aged 40−44 at baseline), the findings may not be generalizable to other age cohorts. For example, in adolescents and young adults at the start of their working lives, norms of job control may be lower and have less impact on mental health. Finally, as the measures of job control, mastery, and mental health were self-reported, the data may be either underreported or overreported due to recall bias.

Concluding remarks

The current study adds to the evidence that low job control is a significant, independent risk factor for common mental disorder, independent of general perceptions of control and other individual differences. The findings underscore the importance of psychologically stressful employment conditions for mental health, and the benefits of considering the workplace as a context for protecting and promoting good mental health.