Cooks and other kitchen workers are exposed to air pollution generated while cooking and frying, such as aerosol oil droplets, combustion products (including fine and ultrafine particles), and organic gaseous pollutants (1–3). The levels and the chemical composition of cooking emissions vary depending on the cooking oil used, the temperature, the kind of food cooked, and the cooking method (3–5).

Several earlier epidemiological studies have indicated an increased risk of myocardial infarction (MI) among cooks and other restaurant workers (6–10), although it is not known whether the excess risk is caused by occupational exposure to cooking fumes, cigarette smoking, passive smoking, or other causes. An increased mortality of MI or other ischemic heart disease (IHD) has been found among female cooks in England and Wales (6), female cooks and other kitchen workers in Finland (7), male British army cooks (8), and male and female cooks and restaurant workers in Sweden (9,10).

There is a well-established association between particulate urban air pollution and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (11–14). A common hypothesis is that inhaled particles cause a systemic inflammatory response that increases the risk of cardiovascular disease (15–18). An elevated risk of MI has been found for some occupational groups with high exposure to particulate air pollution (19–22), as well as among those with occupational exposure to combustion particles (23).

Since cooks and other kitchen workers are occupationally exposed to particles and other air pollutants generated in the kitchen, inhalation of these air pollutants is a possible contributing factor to the increased risk of MI and other IHD previously noted in these occupations.

The aim of this study was to investigate the association between occupation as a cook or other restaurant worker and incidence of MI, using workers in the same socioeconomic group as reference, adjusting for individual information on diabetes and hypertension. The prevalence of daily smokers was compared on a group level.

Methods

Study base

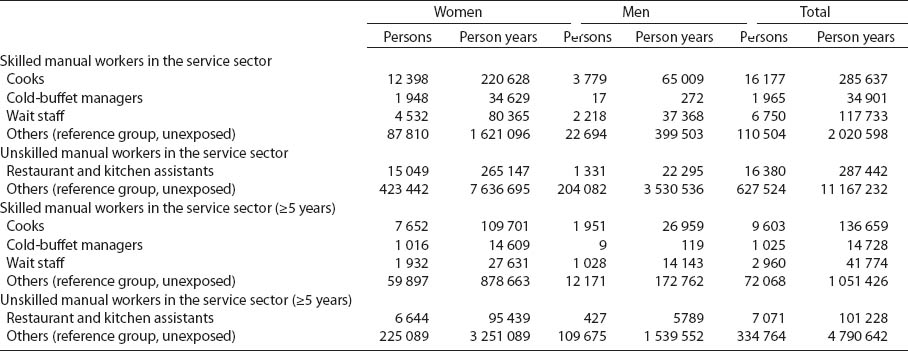

The cohort comprised skilled and unskilled manual workers in the service sector in the Swedish National Census (with individual-level information on all people in Sweden, including demographic data and occupation) of 1985, who were alive on 1 January 1987, totaling 543 497 women and 233 999 men (table 1).

Table 1

Number of persons and person-years under risk for first time acute myocardial infarction during 1987–2005, subdivided by sex and subgroups of cooks and other restaurant workers or reference group. When the cohort was restricted to persons who had worked for ≥5 years, the follow up period was 1991–2005.

First time events of acute MI (International Classification of Diseases, ICD9 code 410 and ICD10 code I21) during the period 1987–2005 were identified through linkage at the individual level (by the personal 10-digit identification number assigned to each person in Sweden for his or her lifetime) to the nationwide Hospital Discharge Register (records all in-patient care in Sweden) and the National Cause of Death Register (records the underlying cause of death among Swedish residents).

The Regional Ethics Committee in Stockholm, Sweden, approved the study.

Information on occupation and socioeconomic status

Information on occupation and socioeconomic status was obtained from the population censuses in 1985 and 1990. We identified cooks (occupational codes 9121 and 9123), cold-buffet managers (code 9124), restaurant and kitchen assistants (codes 9131 and 9132) and wait staff (code 9144) from these censuses by occupational codes corresponding to the Nordic version of the International Standard of Classifications of Occupations (24). Wait staff were included since they belong to a socioeconomic group similar to cooks but are exposed to lower levels of kitchen-generated air pollutants. The comparisons were made with restriction to the same socioeconomic group. For cooks, cold-buffet managers, and wait staff, the reference group comprised skilled manual workers in the service sector. For restaurant and kitchen assistants, the reference group comprised unskilled manual workers in the service sector. In both reference groups, we excluded individuals who had worked as a cook, cold-buffet manager, restaurant and kitchen worker, or wait staff (either in 1985 or 1990). In a second approach, we restricted the cohort to persons who held the same occupation in both 1985 and 1990, with the follow-up period 1991–2005, in order to identify those with a longer duration of exposure.

Information on hypertension and diabetes

We identified cases of hypertension and diabetes in the study population from registers of hospital discharges and deaths between 1987–2005.

Information on smoking habits

Information on smoking habits among Swedish cooks on a group level was obtained from the Swedish National Institute of Public Health, giving the mean percentage of daily smokers among manual workers who described their current or former (before retirement) occupation as “cook”. This information was based on Swedish national public health surveys from 2004–2010, combined with an additional selection of people from certain counties in Sweden during the same time period (including a total of 309 155 persons aged 16–84 years). From the health surveys, we also got the mean percentage of daily smokers among manual workers in Sweden (25).

Statistical analysis

The association between work as a cook or other restaurant worker and MI was estimated through Cox proportional hazards modeling, with separate analyses for men and women. The risk of MI was investigated from 1 January 1987 until first episode of acute MI, death, emigration, or 31 December 2005, whichever occurred first. In case of immigration of a formerly emigrated person in the study base, the person contributed with person-years from the immigration date until any of the events mentioned above occurred. During the follow-up, 9 991 persons (1.3%) emigrated, 4 108 persons (0.5%) immigrated, and 71 366 persons (9.2%) died (the same person could be included in all categories). Information on occupation was determined from the 1985 and 1990 censuses. Subjects who were unexposed in 1985 were classified as exposed from 1990 if the occupational status at that time had changed to an exposed occupation. Subjects who were exposed in 1985 were still considered as exposed (ever worked in the occupation) even if the occupational status had changed in 1990. Hazard ratios (HR) are presented with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Calendar time was used as the underlying time function in the Cox regression. All risk estimates were adjusted for age as a continuous variable. Additional adjustment was made for hypertension and diabetes (as indicator variables) as these diseases may act as possible confounders.

To assess the effect of exposure duration, we restricted one analysis to subjects who worked as a cook or other restaurant worker in two consecutive censuses [ie, subjects who held the same occupational code and socioeconomic position in 1985 and 1990 (as a proxy for a work duration of ≥5 years)]. The corresponding restriction was applied to the unexposed subjects serving as referents.

We also investigated the absolute difference in incidence (risk difference) of MI between cooks and those who never worked as cooks among men and women. The incidence rates were directly standardized, using the age distribution (in five strata) of the entire study base as weights.

Results

During the follow up period 1987–2005, a total of 38 868 cases of acute MI were registered.

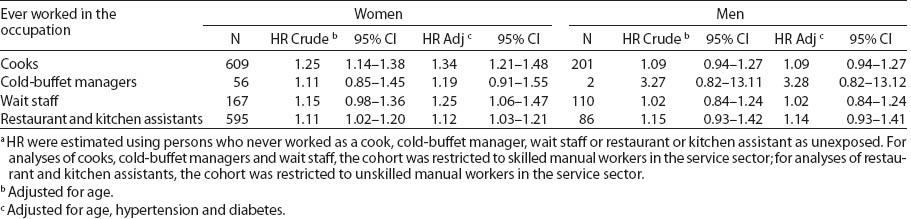

For women, there was a statistically significant increase in adjusted HR for MI among cooks (HR 1.34, 95% CI 1.21–1.48), restaurant and kitchen assistants (HR 1.12, 95% CI 1.03–1.21), and wait staff (HR 1.25, 95% CI 1.06–1.47). The HR was elevated, although not statistically significant, for cold-buffet managers (HR 1.19, 95% CI 0.91–1.55) (table 2). For men, the HR were above unity for all the studied groups, but showed no statistically significant increase (table 2).

Table 2

Hazard ratios (HR) a for acute myocardial infarction among subgroups of cooks and other restaurant workers, calculated with Cox proportional hazards modeling. One person may contribute to both exposed and unexposed person-years in the analyses. [95% CI=95% confidence interval; Adj=adjusted; N=number of cases]

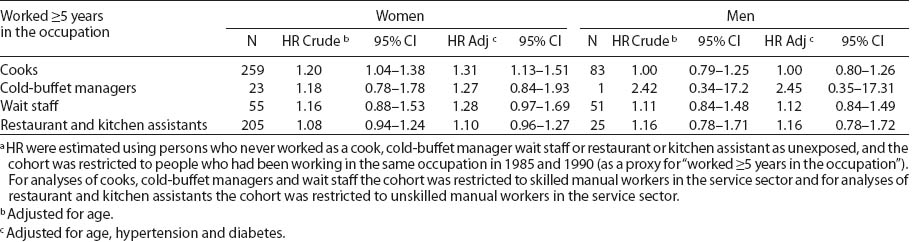

The HR for MI were essentially unchanged by restricting the analyses to those with a work duration of ≥5 years, both among men and women (table 3).

Table 3

Hazard ratios (HR) a for acute myocardial infarction among subgroups of cooks and other restaurant workers with a work duration of ≥5 years, calculated with Cox proportional hazards modeling. One person may contribute to both exposed and unexposed person-years in the analyses. [95% CI=95% confidence interval; Adj=adjusted; N=number of cases]

Women consistently showed higher HR than men. Since women have a lower baseline rate of MI, an apparently higher risk ratio could be produced even if there is a similar difference in absolute disease risk between exposed and unexposed workers among men and women. We therefore analyzed the absolute difference in risk between cooks (exposed) and those who never worked as a cook (unexposed), for both men and women. The absolute difference in risk of MI between cooks and those who never worked as a cook was 4.2 per 10 000 person-years (95% CI 0.9–7.5) for women and 0.5 per 10 000 person-years (95% CI -12.0–13.0) for men.

Among cooks, the percentage who had been admitted to hospital for treatment of hypertension or diabetes during the follow-up period was 0.10% for hypertension and 0.10% for diabetes, respectively, among male and female non-cases. Among cold-buffet managers, the corresponding percentages were 0.19% and 0.19%, among wait staff 0.03% and 0.04%, and among restaurant and kitchen assistants 0.21% and 0.11%, respectively. In all these groups, the occurrence of hypertension or diabetes was lower compared to the reference group of skilled manual workers in the service sector (3.47% and 1.39%, respectively) and unskilled manual workers in the service sector (2.08% and 0.92%, respectively). The difference was somewhat larger among female than male non-cases.

Information from Swedish national public health surveys (not included in the analyses) showed that the age-adjusted (directly standardized using the age distribution in the Swedish population in 2003 as weights) mean percentage of daily smokers among manual workers in Sweden was about 21% for women and 16% for men, during the period 2004–2010, and the percentage of daily smokers decreased gradually during these years. For the same time period, and with restriction to manual workers, the age-adjusted mean percentage of daily smokers among female “cooks” (N=345) was 23% (95% CI 19–28), and 22% (95% CI 19–26) among male “cooks” (N=482). Thus, the female cooks’ smoking habits were similar to the habits of the female manual workers in general, while the male cooks smoked more than male manual workers in general.

Discussion

Occupation as a cook, restaurant and kitchen assistant, and wait staff was associated with a statistically significant increase in HR of MI among women. Men in the same groups showed HR above unity but no statistically significant increase. Women also showed a higher absolute risk difference in MI incidence between cooks and those who never worked as a cook compared to men (although there was an uncertainty in risk difference for males, with wide confidence intervals), indicating that the discrepancy between women and men was not caused by a lower baseline risk among women than among men. Thus, female cooks showed an excess risk of MI both in absolute and relative terms versus other women of similar socioeconomic group. The excess HR for MI among female cooks and other restaurant workers persisted when the study was restricted to persons holding the same type of job in two censuses, although with a statistically significant increase only among female cooks. This type of restriction most likely leads to a reduced misclassification of occupation as well as a reduced proportion of persons with short work duration.

Since we found an increased risk of MI only among female, but not male, cooks and kitchen workers, as well as among female wait staff exposed to lower levels of cooking fumes, our results do not support the hypothesis of cooking fumes as an explanation for the increased MI risk. There are possible differences in occupational exposure between men and women, but the fact that there was no tendency for an exposure–response trend regarding work duration for cooks and other kitchen workers gives even less support for the hypothesis of cooking fumes as an explanation. However, there is some evidence in the literature of a stronger association between particulate air pollution exposure and fatal coronary heart disease (26, 27) and atherosclerosis (28) among women than men. The reasons for these sex-differential observations are unclear but several hypotheses have been discussed, such as a greater particle deposition among females than males as well as a deposition more localized within the lung in females (29). There are also studies indicating that women may be more sensitive than men to the harmful effects of smoking (30–32), eg, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies showed that the pooled adjusted female-to-male risk rate ratio of smoking compared to not smoking for coronary heart disease was 1.25 (95% CI 1.12–1.39) (32). The authors discuss that it is unclear whether the mechanisms underlying these sex differences in risk are biological or related to differences in smoking behavior between men and women. Although the waitresses in our study were not heavily exposed to cooking fumes they were most likely exposed to second-hand smoke before smoking was banned in Swedish restaurants in 2005, and this could possibly have contributed to their increased MI risk.

Possible alternative explanations for the discrepancy in risk between male and female restaurant workers are confounding from smoking, overweight, physical inactivity, job strain, or other risk factors, although potential confounding from lifestyle factors was limited by restricting the analyses to the same socioeconomic group. Among women, all studied occupational groups showed higher HR after adjustment for hypertension and diabetes, confirming a lower prevalence of these risk factors among female cooks and other restaurant workers than among other manual workers in the service sector. However, these differences in the occurrence of hypertension and diabetes may also indicate a weakness of the study, with the groups possibly not being fully comparable. Examples of typical professions in the reference group of skilled manual workers in the service sector include hairdressers, hotel cleaners, enrolled nurses and engine drivers and among unskilled manual workers in the service sector sales assistants, nursing assistants, bus and truck drivers, and office cleaners. We did not have information on whether a person had been under treatment for hypertension or diabetes outside institutional care. This is a limitation but the registration in this study at least covers people suffering from a rather serious disease. However, further possible residual negative confounding (leading to an underestimation of risk) may exist from hypertension and diabetes.

We do not have individual smoking data in the present study. However, we have information on smoking habits on a group level for cooks in Sweden during the time period 2004–2010 (25), although this information is approximate and does not cover the time period before 2004. The proportion of daily smokers among male cooks was higher than among male workers in general, yet no increased HR of MI was observed. The proportion of daily smokers among female cooks was similar to that of female workers in general, but they still showed an increased HR of MI. Therefore, differences in smoking habits between cooks and other manual workers do not seem to explain the excess risk among female cooks. A limitation of the smoking data is that the comparator information on the proportion of daily smokers was for manual workers in Sweden, and not specifically for manual workers in the service sector.

There is a possibility that female cooks, restaurant and kitchen assistants, and wait staff suffer from higher job strain than other female manual workers in the service sector, thus contributing to their increased MI risk. However, information from Statistics Sweden in 2001 regarding work-related health problems in the last 12 months, showed that work-related mental stress was not more commonly reported by cooks, waiters/waitresses or kitchen and restaurant workers compared with the total occupationally active population in Sweden (33). Among females (129 female cooks and 261 female restaurant and kitchen assistants participated), 8.4% of cooks and 6.6% of kitchen and restaurant workers reported health problems due to mental stress at work, compared with 11.2% among the total female working population. However, this information does not cover all types of stress or job strain.

In the present study, the cooks and kitchen workers worked in all types of restaurants, and we do not have individual information on the type of restaurant or exposure levels of air pollution. The exposure to air pollution in restaurant kitchens varies largely depending on factors such as the kind of food cooked, method of cooking, ventilation system etc. In Norwegian à la carte restaurants, personal measurements of total particle exposure in the breathing zone of the cook during work showed a mean mass concentration of 1.93 mg/m3 (range 0.32–7.51 mg/m3) during the four peak hours with respect to the number of customers in the restaurant (34). Measurements of inhalable particulates (PM10) were performed among kitchen workers in 29 Chinese restaurants in Guangzhou, China, during lunch- and dinnertime (35). These showed an average of 0.13 mg/m3. In an ongoing Swedish study by Lewné et al (personal communication), personal samplings of particle exposure levels during full work shifts for cooks and kitchen workers thus far show a tendency of higher levels in large-scale kitchens (large kitchens, prepare meals for big companies, schools and other institutions mainly at lunchtime) compared to European (often small kitchens, prepare fewer meals but for a longer period each day), fast food, and Asian kitchens.

Previous studies of coronary heart disease among cooks and kitchen workers mainly studied mortality of MI or other IHD (6–9). The strengths of the present study are the large study base and the information on both incident and fatal cases of MI. We could also limit potential confounding by smoking and other risk factors by restricting the study to workers in the same socioeconomic group as well as adjusting for diabetes and hypertension, and for cooks we had information on smoking on a group level. Furthermore, we had the possibility to compare incidence rates in both absolute and relative terms among cooks. However, since males have a higher baseline incidence of MI than females, this would also make it more difficult to detect an increased risk among men, and the group of male cooks in the study is also considerably smaller than the female group.

In accordance with our results, many previous studies showed an excess risk of MI or IHD among female cooks and kitchen workers, but some studies also showed an excess risk among males. A study on occupational mortality of women in England and Wales showed an increased mortality of MI or other IHD among female cooks compared to other employed women (6). In a Finnish study, the standard mortality rate (SMR) for fatal MI was increased among female (SMR 1.17, 95% CI 1.06–1.31) but not male kitchen assistants, and the SMR for other IHD was increased for female but not male cooks and other kitchen staff (SMR 1.30, 95% CI 1.11–1.54), kitchen assistants (SMR 1.40, 95% CI 1.18–1.65), and restaurant waiters, compared to other economically active women or men (7). However, male British retired army cooks were also found to have elevated death rates from IHD (SMR 1.42, 95% CI 1.13–1.76) compared to the national population as well as compared to a referent group of other men retired from the army and supposed to have had a similar work situation regarding physical training and irregular hours (8). In a Swedish study, an increased risk due to IHD was observed among both male (SMR 1.33, 95% CI 1.12–1.56) and female (SMR 1.29, 95% CI 1.20–1.37) cooks and cold-buffet managers and kitchen assistants as well as among male waiters and head waiters, compared to all gainfully employed men or women (9). Kitchen assistants were found to be one of ten occupations (in the 1970 and 1975 censuses) among Swedish women, but not men, with an increased incidence of first time MI during the period 1976–1984, but the excess risk did not persist after adjusting for socioeconomic group (10). Only one of the above mentioned previous studies adjusted for socioeconomic group (10), and no study had information on individual smoking habits or other lifestyle factors.

Concluding remarks

We found an increased risk of MI among female cooks and restaurant workers, with the exception of cold-buffet managers. Internal comparisons do not support that the excess was caused by exposure to cooking fumes since no greater risk was found among those employed ≥5 years, and no excess risk was found among any group of male restaurant workers. In addition, an excess risk was found among female waitresses (who were not heavily exposed to cooking fumes) similar to other female restaurant workers. However, the possibility of cooking fumes as a risk factor for MI cannot – with certainty – be ruled out in the present study. Possibly, the excess risk among female waitresses could be explained by exposure to second-hand smoke at work, and it may be more difficult to detect an increased risk in the smaller group of men since men have a higher baseline incidence of MI. Potential confounding from lifestyle factors was limited by restriction to the same socioeconomic status and adjustment for hypertension and diabetes. Differences in smoking habits between cooks and other manual workers do not seem to explain the excess risk among female cooks. There is a possibility that female cooks, restaurant and kitchen assistants and wait staff suffer from higher job strain than other female manual workers in the service sector.