Economic difficulties are a domain of socioeconomic circumstances not captured by conventional domains of socioeconomic position. Unlike income, the measure to which they might be assumed to be most closely related, economic difficulties capture sufficiency in relation to need. Therefore, examining these difficulties and their change over time provides an opportunity to increase our understanding of socioeconomic inequalities in health. A broader approach may be useful as socioeconomic position includes not only social but also financial and material circumstances that are not captured with any single indicator (1–3). Difficulties in affording adequate food or clothes and paying bills represent concrete measures of material socioeconomic circumstances (4). Accordingly, economic difficulties have been shown to be associated with health-related outcomes in many previous studies independent of conventional socioeconomic position such as occupational class, income, and education (5–11). Moreover, economic difficulties can exist at all income levels with adverse health-related consequences (7, 10).

Health functioning is widely studied and reflects health status and its effect on an individual’s ability to perform everyday tasks (12–14). The social patterning of health functioning is well-established (15, 16). Previous studies have, however, been mainly cross-sectional (17). A French study found that the least educated and those with the lowest occupational class had the greatest decline in health over time (18). The worsening trends suggested that inequalities in health functioning were widening. Lower occupational class was also found to be associated with a greater decline in health functioning in our earlier studies among the British (19) and the Finnish (20) occupational cohorts.

There are few prospective studies examining additional socioeconomic determinants of health functioning such as economic difficulties. Nonetheless, previous studies have focused on other indicators of economic situation such as problems paying mortgage debt, and perceived or objective financial troubles and subsequent psychological health or depression (21, 22). These studies have found associations between such economic situations and depression, albeit they have also raised questions of reverse causality, health selection, and unmeasured or unobserved third factors. Although the association between personal economic situation measured objectively and health was weak, (21) subjective and objective measures were correlated and the effects of the objectively measured economic situation on depression were suggested to be mediated via perceived financial troubles. Financial hardships perceived over the life course have also been found to be associated with self-rated health, chronic conditions, and other health measures, such as depression and functional limitations, among adults aged ≥65 years. Effects were exacerbated if such hardships were perceived repeatedly (23).

Our earlier cross-sectional studies showed that economic difficulties are associated with physical functioning (8, 24) and common mental disorders (9, 10). We have also previously reported persistent economic difficulties to be associated with incident coronary events (25) and sleep problems (5). In our recent study among Finnish public sector employees, changes in economic difficulties were associated with subsequent sickness absence spells of various lengths (26). However, the contribution of changes in economic difficulties to decline in both physical and mental health functioning is poorly understood. Moreover, as the social patterning of physical and mental health appear to vary (10, 17, 27), both dimensions need to be examined to establish whether changes in economic difficulties affect them equally.

As childhood economic difficulties contribute to poorer mental health and physical functioning (8, 24), these need to be taken into account when examining the association between economic difficulties and health functioning. This also helps rule out potential sensitivity to the exposure and lifetime adversity. Additionally, because income and employment status are also associated with health functioning (8, 28) and are determinants of economic difficulties, their potential confounding of the association needs to be taken into account.

The main aim of this study was to examine associations between changes in economic difficulties and poor physical and mental functioning among middle-aged employees, while considering the effects of baseline health functioning, income level, employment status and other covariates on the examined associations. Additionally we tested the association in two prospective cohorts of middle-aged, white-collar civil servants in Finland and the UK. Although these countries share many similarities, they differ in their level of employment protection, income inequality, and welfare regimes: Finland represents the Nordic social democratic model and the UK the liberal welfare state model (29–31). Common and divergent patterns across countries can identify contextual determinants of an association as well as indicate the robustness and generalizability of findings compared to findings generated in a single setting.

Methods

Participants

Data were derived from prospective employee cohorts from Finland (32) and the UK (33). Baseline data for the Finnish Helsinki Health Study were collected in 2000–2002 among 40–60-year old employees of the City of Helsinki Finland (N=8960, response rate 67%). The follow-up survey was mailed to all baseline respondents in 2007 (N=7332, response rate 83%). For the current study, we included all those who had participated in both surveys. Manual employees were excluded as the British cohort only comprised white-collar employees. The final sample analyzed comprised 6328 women and men.

British data were derived from the Whitehall II Study, a cohort of white-collar civil servants from 20 London-based civil service departments. All participants were aged 35–55 years at baseline in 1985–1988 (N=10 308, response rate 73%). Several follow-up surveys have been conducted since baseline. To have comparable data in terms of age and time period, we used the phase 5 survey data collected in 1997–1999 (N=7870, response rate 76%) as baseline for the present study, and phase 7 data collected in 2003–2004 (N=6967, response rate 68%) as the follow-up. For comparability with Helsinki Health Study, where all participants were employees of the City of Helsinki at baseline, we included only those Whitehall II participants who were employed at phase 5 (around 64% of the sample) and had also participated at phase 7 (N=4350).

Ethical approvals for the Helsinki Health Study were received from the Department of Public Health, University of Helsinki, and the City of Helsinki health authorities and, for the Whitehall II Study, from the University College London ethics committee.

Measures

Economic difficulties

Economic difficulties were measured at baseline and follow-up using two items asking about frequency of difficulties regarding the purchase of food and clothes (five response alternatives ranging from “always” to “never”) and paying bills (five response alternatives ranging from “very little” to “very much”) (4). Responses were first combined to form three categories of economic difficulties at both time points: none, occasional, and frequent. Those with no economic difficulties at both time points were used as a reference category in all the analyses. Initial analyses were conducted to examine all categories of change: increases from none to occasional, none to frequent, and occasional to frequent, and vice versa for decreases (data not shown). As patterns of association across these groups were very similar, we combined all increases and decreases to form two change categories: increasing and decreasing economic difficulties. Additionally, persistent occasional and frequent economic difficulties over the follow-up were examined. Further details of the measurement of economic difficulties can be found elsewhere (5, 26).

Health functioning

Physical and mental functioning was measured in both cohorts using identical Short Form 36 (SF-36) questionnaires at baseline and follow-up (13, 14, 34). The Finnish version was a translation (35). The SF-36 comprises 36 items and 8 subscales from which physical and mental component summary scores were calculated. Subscales indicate physical functioning, role limitations due to poor physical health, bodily pain, general health perceptions, vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, and mental health. The component summary scores range from 0–100 with higher scores indicating better physical and mental functioning.

In this study, the scores were dichotomized to indicate poor physical and mental functioning using the lowest quartile as a cut-off point at baseline and follow-up. Similar procedures have been applied in previous studies (8, 28, 36, 37). Separate cut-off points were calculated for women and men in both cohorts at baseline and follow-up. Physical and mental component summaries were used, and their reliability has been shown to be higher than that of the separate subscales (13). Furthermore, the SF-36 questionnaire has been shown to have good psychometric properties, overall high internal consistency and construct validity as well as high test-retest reliability (12, 14).

Covariates

Sex, age, childhood economic difficulties, baseline and follow-up income, employment status at follow-up, and baseline health functioning were included as covariates. Childhood economic difficulties were measured by a question asking whether there had been any serious financial difficulties in the family before the respondents turned 16 years. Household income was self-reported at baseline and follow-up and comprised all income after taxes, including any welfare benefits and other sources of income. In the Finnish cohort, time reference was an average month, while in the British cohort it was the previous 12 months. We weighted the income by the number of children and adults living in the household (38). Finally, weighted household disposable income was divided into quartiles using separate cut-off points for women and men. Employment status at follow-up was measured comparing those continuously employed to those who had retired or left the labor market over the follow-up.

Statistical analysis

We used logistic regression analysis to examine the associations between changes in economic difficulties and poor physical and mental functioning. Associations are expressed as odds ratios (OR) and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Interactions between sex and health functioning were tested but not found, suggesting that the associations were similar for women and men. Thus, all analyses were conducted in pooled data. Analyses were initially adjusted for age and sex (model 0) and then additionally adjusted for childhood economic difficulties (model 1), baseline and follow-up income (model 2), employment status at follow-up (model 3) and then all these covariates together (model 4). Model 5 was a full model adjusted for baseline health functioning in addition to all the covariates in model 4. In addition, similar models were fitted using linear regression and continuous scores for health functioning as outcomes.

We used multiple imputation to control for missing values. The analysis was carried out with the aregImpute function in the Hmisc package for R software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Multiple imputation was based on additive regression, bootstrapping, and predictive mean matching (39). Ten imputed datasets were created, assuming that items were missing at random (39). These estimates were obtained by averaging across the results from each of these ten datasets using Rubin’s rules. Complete case analyses were also carried out and these produced similar results (data not shown). To avoid redundant loss of data and potential selection, we preferred to retain all participants and examine associations using the imputed data. Complete case and other sensitivity analyses were carried out with the SAS statistical program, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) as well as the R software.

Results

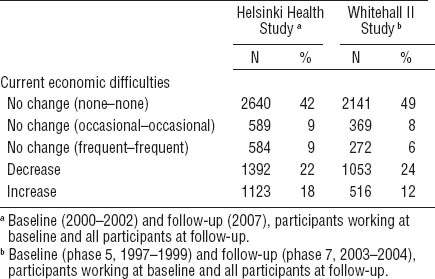

Half of the participants reported no economic difficulties at either time point (table 1). Decreasing economic difficulties were more prevalent than increasing ones in both cohorts. However, 18% reported increasing economic difficulties in the Finnish cohort compared with 12% in the British cohort, while an additional 9% of the Finnish participants and 6% of the British participants had persistent frequent economic difficulties.

Table 1

Economic difficulties at baseline and follow-up in the Finnish Helsinki Health (N=6328) and British Whitehall II (N=4350) studies.

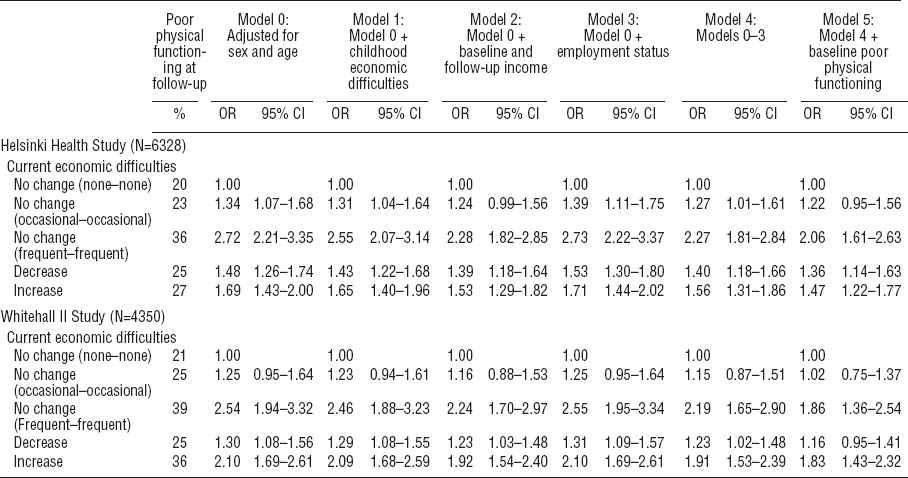

In the Finnish cohort, 36% of those with persistent frequent economic difficulties and 27% of those with increasing economic difficulties reported poor physical functioning, compared to 20% of those with no economic difficulties (table 2). The corresponding figures for the British cohort were 39%, 36%, and 21%, respectively. Prevalence of poor physical functioning at follow-up was 25% among those with decreasing economic difficulties in the Finnish and British cohorts.

Table 2

Associations between economic difficulties at baseline and follow-up and poor physical functioning at follow-up. [OR=odds ratios; 95% CI=95% confidence intervals]

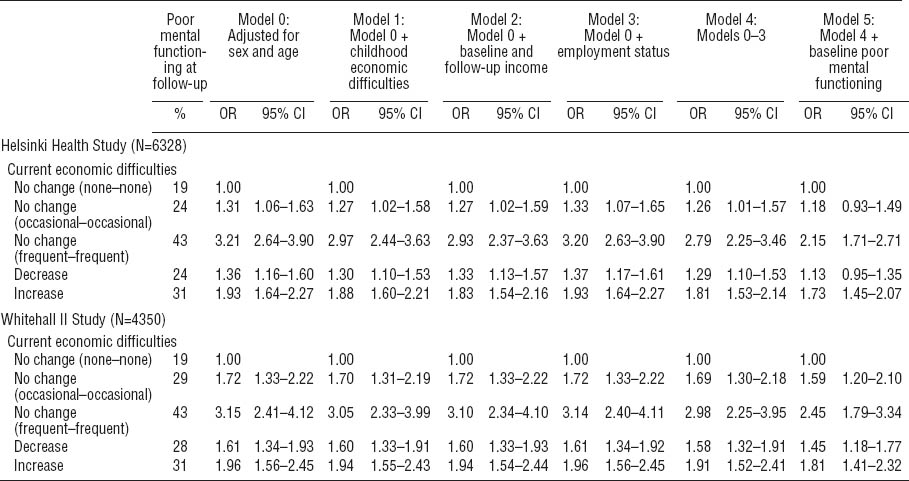

Of those with persistent frequent economic difficulties in the Finnish and the British cohorts, 43% reported poor mental functioning at follow-up (table 3). Poor mental functioning was also prevalent among those with increasing economic difficulties (31% in both cohorts). In both cohorts, the prevalence of poor mental functioning at follow-up was 19% among those with no economic difficulties and 24% and 28% among those with decreasing economic difficulties in the Finnish and British cohorts, respectively.

Table 3

Associations between economic difficulties at baseline and follow-up and poor mental functioning at follow-up. [OR=odds ratios; 95% CI=95% confidence intervals]

Associations between economic difficulties and poor physical functioning

After adjusting for age and sex, associations were found between changes in economic difficulties and physical functioning in both Finnish and British cohorts (table 2). In the Finnish cohort, persistent occasional (OR 1.34, 95% CI 1.07–1.68) and frequent (OR 2.72, 95% CI 2.21–3.35) economic difficulties were associated with poor physical functioning at follow-up. Those with increasing (OR 1.69, 95% CI 1.43–2.00) and decreasing (OR 1.48, 95% CI 1.26–1.74) economic difficulties had higher odds for poor physical functioning at follow-up. Adjustments for the covariates had mainly minor effects on these associations. After full adjustment for socioeconomic factors and baseline physical functioning, the associations were somewhat attenuated but persistent frequent and increasing and decreasing economic difficulties remained associated with poor physical functioning at follow-up.

The patterns of associations were similar in the British cohort (table 2). As in the Finnish cohort, after adjustment for age and sex, persistent frequent (OR 2.54, 95% CI 1.94–3.32), increasing (OR 2.10, 95% CI 1.69–2.61) and decreasing (OR 1.30, 95% CI 1.08–1.56) economic difficulties were associated with poor physical functioning at follow-up. Again, adjustments for the covariates mainly had minor effects on these associations. Thus, persistent frequent and increasing economic difficulties remained associated with poor physical functioning, while the associations for persistent occasional and decreasing economic difficulties were attenuated and disappeared.

Associations between economic difficulties and poor mental functioning

As with physical functioning, associations were found between changes in economic difficulties and poor mental functioning at follow-up in both Finnish and British cohorts (table 3). In the Finnish cohort, persistent occasional (OR 1.31, 95% CI 1.06–1.63), frequent (OR 3.21, 95% CI 2.64–3.90), increasing (OR 1.93, 95% CI 1.64–2.27), and decreasing (OR 1.36, 95% CI 1.16–1.60) economic difficulties were associated with poor mental functioning at follow-up. After adjustment for socioeconomic factors and baseline mental functioning, the associations again remained for increasing and persistent frequent economic difficulties, but were somewhat attenuated and disappeared for persistent occasional and decreasing economic difficulties.

In the British cohort (table 3), associations between changes in economic difficulties and mental health functioning were, again, very similar to the Finnish cohort and to physical functioning. Persistent occasional (OR 1.72, 95% CI 1.33–2.22), frequent (OR 3.15, 95% CI 2.41–4.12), increasing (OR 1.96, 95% CI 1.56–2.45) and decreasing (OR 1.61, 95% CI 1.34–1.93) economic difficulties were associated with worse mental health functioning. All these associations remained after adjustment for all the covariates.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted several sensitivity analyses to confirm our findings. First, reverse causality was examined. We examined whether changes in physical and mental health functioning were associated with changes in economic difficulties. Thus economic difficulties at follow-up was used as an outcome while adjusting for baseline economic difficulties. In the Finnish cohort, persistently poor and an improvement or deterioration in physical and mental functioning were associated with changes in economic difficulties at follow-up, after adjusting for baseline economic difficulties and all covariates (OR range 1.3–2.2). The strongest associations were found for persistently poor health functioning. In the British cohort, only persistently poor health functioning remained associated with changes in economic difficulties at follow-up. Second, we examined physical and mental health functioning using SF-36 component sum scores. The associations remained broadly similar, as increasing and persistent economic difficulties were associated with a higher decrease in the physical and mental sum scores compared to the change in score of those with no economic difficulties at either point in time. These associations remained after full adjustment. Third, to confirm that the associations are not sensitive to the selected cut-off point (the lowest quartile), we also used the lower third as a cut-off point to examine poor health functioning. Again, all the associations remained. Fourth, to confirm whether the effects of physical health remain after controlling for mental health and vice versa, we simultaneously adjusted for both physical and mental health functioning. This had negligible effects on the reported associations. Fifth, associations observed for the combined measure of economic difficulties were similar when the two items (ie, difficulties affording adequate food and clothes and paying bills) were analyzed separately (data not shown). Finally, the results remained essentially unchanged when those reporting poor functioning at baseline were excluded (data not shown).

Discussion

Main findings

In this longitudinal study of middle-aged occupational cohorts in Finland and the UK, both persistent and increasing economic difficulties were associated with poor physical and mental health functioning at follow-up. These associations remained after adjustment for a range of covariates, including baseline functioning, childhood economic difficulties, baseline and follow-up income, and employment status. Those with decreasing economic difficulties also tended to have poorer functioning compared to those with no economic difficulties at either point in time.

Interpretation

This study provided novel evidence showing that changes in the economic difficulties faced by an individual, in particular increasing and persistent economic difficulties are risk factors for both poor physical and mental health functioning. The fact that these associations were replicated in occupational cohorts from two national contexts, were similar among both women and men, and survived all adjustments, highlights the robustness of our findings. Furthermore, as the adjustment for other socioeconomic factors did not remove or even attenuate the associations, this confirms that economic difficulties are unlikely to be just a proxy for income level or changes in income and employment status. In other words, the lack of attenuation produced by adjustment for baseline and follow-up income shows the importance of economic difficulties as risk factors for physical and mental health functioning across the socioeconomic spectrum separate from changes in income level. This confirms earlier studies showing that the associations of economic difficulties with other health-related outcomes remained after considering multiple socioeconomic circumstances (5, 9, 25).

Previous evidence on changes in economic difficulties and health functioning is lacking. However, a study focused on economic hardship measured in repeated surveys included questions such as the need to borrow money to pay bills and changing food purchasing behaviors to save money (40). Such economic hardship in early middle-age was associated with depression later in life. In addition, problems paying debt and experiencing financial stress have been associated with mental health problems (21, 22). The present results are also in line with our earlier studies that have shown the significance of changes in economic difficulties for poor sleep and coronary events (5, 25). In addition to adjustment for socioeconomic circumstances, behavioral and biological factors made only a minor contribution to the association between persistent economic difficulties and coronary events in the earlier study (25).

Although the effects of changes in economic difficulties on health functioning have not been studied, earlier research has examined income as a measure of economic situation. Persistent economic hardship as indicated by low household income has been associated with subsequent poor physical and mental health functioning (41). Cumulative exposure to low economic resources studied using register-based data on income and wealth has recently been shown to lead to sickness absence (42), indicating poor functioning among employees (43, 44). Income levels are subject to change, and one might assume that the observed associations could be explained by further measures of material circumstances reflecting long-term economic (dis)advantage. We therefore additionally controlled for housing tenure, but this had negligible effects on the associations. We found that the associations between economic difficulties and functioning remained even after adjusting for childhood economic difficulties, suggesting that early sensitization is unlikely to have led to over-reporting of current economic difficulties.

As self-reported data on both exposures and outcomes were used, negative affectivity (45) or perceived lack of control over one’s life are potential sources of bias. These might contribute to a disposition to over-report both economic difficulties and poorer health functioning independent of income level or other examined factors. It has been suggested that economic difficulties act as a stressor and might affect health via a decrease in sense of mastery (46). It is also possible that change in both economic difficulties and health functioning may be driven by unmeasured third factors, although adjustment for the two most likely candidates, income and employment status, had little effect on the associations observed. More scrutiny is thus needed to shed light on the reasons underlying the associations between changes in economic difficulties and poor physical and mental health shown in earlier studies (8, 9) as well as the associations with poor physical and mental functioning in the present study.

Decreasing economic difficulties were also associated with poorer physical and mental functioning at follow-up. Although this might appear contrary to expectations, this group included those with frequent difficulties at baseline and occasional difficulties at follow-up, and thus a worse situation at both points in time compared to those not reporting economic difficulties at either time (the reference group). Additionally as the change in economic difficulties may have occurred at any point over the 5–7 year follow-up period, some participants’ circumstances will have only very recently improved and one would expect a lag between improved financial circumstances and improved functioning. The assumption that adverse events, such as economic difficulties may have long-lasting or residual effects is in line with earlier prospective findings on job security in the British cohort (47). Thus, poorer health at follow-up was observed among employees whose job was insecure at baseline but secure at follow-up. However, a study from the USA suggested the effects of earlier financial hardship on health were obviated if financial hardships were not perceived later on (23). Earlier findings from the Finnish cohort showed a decrease in economic difficulties after full adjustment to be weakly associated only with long medically certified sickness absence spells, while associations with shorter spells were attenuated (26).

Finally, the associations between economic difficulties and functioning were similar in Finland and the UK. Although there are differences between the two countries in employment protection and benefits, such differences are more likely to affect the proportion of people subject to economic difficulties than the association between economic difficulties and health given that healthcare provision is universal in both countries. Additionally, as both Finnish and British participants were white-collar civil servants, levels of employment protection and benefits were relatively similar in the two cohorts.

Methodological considerations

This study had some limitations. First, data collection in the Helsinki Health Study largely followed the Whitehall II Study procedure, but the Finnish baseline data were from 2000–2002, whereas the British baseline data were from 1985–1988. To have comparable data in terms of age, time period, and employment status, we used phase 5 from Whitehall II and included only participants who were still employed at phase 5. However, the data remained broadly representative of the target population and non-response and attrition are thus unlikely to have distorted the main findings (33). Additionally, attrition is unlikely to be a major source of bias when examining social inequalities in health in these cohorts (10). Also mortality risk associated with non-response is similar at baseline and follow-up (48). In the Finnish data, non-response and attrition analyses suggest that the data are broadly representative of the target population, except that men, younger respondents, those in lower socioeconomic positions, and those with long sickness absence have been slightly over-represented amongst the non-responders (32).

Second, we only examined middle-aged women and men employed at baseline. Thus these results are likely to be conservative and associations stronger in the general population (49).

Third, the measures of economic difficulties and health functioning were based on self-reports. Consequently, common method variance cannot be ruled out as an explanation for the findings, although we used a measure of change as our exposure that considerably reduces this risk. It has further been shown that perceived economic situation is unlikely to be biased by the respondent’s own mental health (22). The possibility of adaptation to straightened circumstances may also have resulted in some misclassification of economic difficulties at follow-up. It is possible that our observed associations were stronger than would be the case for objective measures of personal economy as our measure of economic difficulties captures both sufficiency and need. Although self-reported, the SF-36 has been shown to be a valid tool to detect changes in health over time (50).

Fourth, the 5-year follow-up period was relatively long and fluctuations in economic difficulties between baseline and follow-up cannot be ruled out. There might also be other time-varying covariates. However, with regard to factors that might confound the association between economic difficulties and health functioning, family income level and changes in family income and employment status were assumed to be the most likely candidates, but the effects of the adjustments were minor. Additionally, adjusting for family income at baseline and follow-up partly accounts for other economic changes such as changes in marital status and living arrangements because number of adults and children living in the same household was taken into account in the income variable.

Fifth, causal inferences are not warranted as we are unable to confirm whether decline in functioning occurred before or after the change in economic difficulties over the follow-up. However, earlier studies suggest that reverse causality is unlikely to explain the associations substantially, as economic resources measured by income are stronger predictors of subsequent poor health than vice versa (41, 42, 51). As reported in our sensitivity analyses, changes in health functioning were associated with economic difficulties at follow-up suggesting there is some reverse causality in the associations. Also earlier evidence suggests that the associations between debt and mental health are bidirectional (22). The associations between changes in physical functioning and economic difficulties were, nonetheless, weaker and more inconsistent than those reported. This is in line with an earlier study showing that material resources are more likely to contribute to worsening health although health selection into a poorer material situation was also found (42).

Sixth, use of dichotomous measures might have resulted in loss of information, as some changes may have remained undetected due to the use of cut-off points. However, as reported in our sensitivity analyses, continuous measures provided similar evidence about the contribution of economic difficulties to subsequent changes in health functioning. It should be noted though that the interpretation of continuous measures is different as the dichotomous measures specifically focus on the poor end of health functioning.

Seventh, adjustment of the association between economic difficulties and physical or mental functioning – for mental or physical functioning, respectively – had little effect. This is to be expected, as the SF-36 physical and mental component summaries have been constructed to minimize the correlations between these two components (13, 34). Although it is possible that poorer mental health may lead to economic problems (22), the associations between economic difficulties and subsequent physical and mental health functioning independent of baseline mental health suggest that economic difficulties remain of significance for health and that selection is unlikely to account for the associations. As changes in economic difficulties have also been associated with subsequent coronary heart disease (25) and sickness absence (26), this further highlights their role as risks factors for both physical and mental health.

Our study also had strengths. First, we were able to test the associations using comparable prospective data from two occupational cohorts, which adds to the external validity and generalizability of the results. The exposures and the outcomes were identical in both cohorts. Second, similar covariates were available. Most importantly, baseline and follow-up income and employment status were available for both cohorts enabling us to control for these two major potential confounders. Third, the SF-36 was available at baseline and follow-up in both cohorts, enabling us to examine associations between economic difficulties and both physical and mental health functioning. Finally, the ability to adjust for health functioning at baseline strengthened the evidence that economic difficulties precede poor health functioning.

Concluding remarks

Both persisting and increasing economic difficulties were associated with a decline in physical and mental health functioning among late middle-age employees from the UK and Finland. As the associations remained robust to changes in income and employment status as well as baseline health, this study highlights the need to consider economic difficulties when tackling inequalities in health and their changes over time.