Sleep duration has been associated with risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and all-cause mortality in prospective studies (1–10). A U-shaped association where both short and long sleepers are at increased risk is generally accepted for all-cause mortality and has been confirmed in two recent meta-analyses (11, 12). The same has been observed among those developing or dying of cardiovascular outcomes (13). Whereas several studies have shown associations between sleep duration and CVD mortality risk among women (1–7, 11, 14, 15), the associations among men remain more inconsistent (1, 2, 4, 7, 14–17). Some studies show an increased risk for CVD mortality among short sleeping men (1, 15), long sleeping men (2, 15), or no associations (4, 6, 7, 14, 16, 17). The relationship remains unsettled for more specific causes of mortality like death from ischemic heart disease (IHD) (1, 4, 15, 17).

The pathophysiological mechanisms through which sleep duration could increase the risk of IHD mortality may be manifold and vary across individuals, including increased sympathetic nervous activity, activated pro-inflammatory response, and effects on the hypothalamus pituitary adrenal axis (18, 19). These pathways have also been suggested to explain how psychological factors may be risk indicators for IHD mortality (20). Over the past years, numerous studies have evaluated the association between CVD and psychological stress, eg, work-related psychosocial factors [reviewed in (20, 21)] and leisure-time factors such as major life events (22).

Thus associations between sleep duration or psychological stress during work or leisure time on the one hand and IHD/all-cause mortality on the other have been studied extensively over the past years. Yet, the results are inconsistent. Several theories [eg, the psychophysiological effort-recovery theories (23, 24), the theory of allostasis (25, 26), and the cognitive activation theory of stress (27)] imply that it is a combination of short sleep duration and stress rather than sleep duration and stress independently that is important for the development of disease and mortality. However, to our knowledge, this has not been scientifically investigated. As a result, using a large cohort of middle-aged men in the Copenhagen Male Study with a 30-year follow-up, we prospectively examined the following research questions: (i) Is sleep duration independently associated with IHD mortality and all-cause mortality? (ii) Does psychological stress during work and leisure time modify the association between sleep duration and IHD mortality? (iii) Do use of tranquilizers/hypnotics modify the association between sleep duration and IHD mortality?

Methods

Study design and population

The present study is a prospective cohort study with 30 years follow-up based on the Copenhagen Male Study, which was established in 1970–1971. All men aged 40–59 years at 14 companies in Copenhagen, covering the railway, public road construction, military, post, telephone, customs, national bank, and the medical industry, were invited to participate. In total, 5249 men, 87% of potential participants, signed up (28, 29).

The examination consisted of a questionnaire, a short interview, and a clinical examination including measurements of height, weight, blood pressure, and physical (cardiorespiratory) fitness. Indirect measurement of cardiorespiratory fitness (VO2Max) was performed using a bicycle ergometer. Thirty-five men with orthopedic problems unable to perform the bicycle test were excluded from the study.

Information about sleep duration, perceived psychological pressure during work and leisure time, lifestyle, and general health, including history of myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, and intermittent claudication was obtained from the questionnaire (30). One of the authors clarified the information given in the questionnaire in the ensuing interview with each subject.

Sleep duration

Participants reported their daily number of hours of sleep in categories: <6, 6–7, 8–9, and >9 hours. The distribution of answers in these groups was: 5.6%, 77.7%, 16.3%, and 0.4%, respectively, among men eligible for the study. Due to the small number of men reporting >9 hours sleep, the latter two groups were pooled for the analyses. Accordingly, respondents were classified as short (<6 hours), medium (6–7 hours) and long (8–9 and >9 hours) sleepers.

Potential markers of psychological stress

Psychological stress was assessed through three questions: (i) “Are you under psychological pressure when performing your work?” Answer options were: “rarely” and “regularly”. (ii) “Are you under psychological pressure in your leisure time?” Answer options were: “rarely” and “regularly”. (iii) “Do you take tranquilizers or sleep medicine?” Answer options were: “rarely”, “regularly” and “never”.

Lifestyle factors

Alcohol

Participants also reported their daily average alcohol consumption as the number of alcoholic beverages consumed per day in categories: 0, 1–2, 3–5, 6–10, and >10 drinks.

Leisure-time physical activity

This was assessed by the question: “Which description most precisely covers your pattern of physical activity in leisure time?”. The response categories were: (i) “You are mainly sedentary eg, you read, watch television, and go to the pictures. In general you spend most of your leisure time performing sedentary tasks.” (ii) “You go for a walk, use your bicycle a little or perform activity for ≥4 hours/week, eg, light gardening, leisure-time building activity, table tennis and bowling.” (iii) “You are an active athlete, run, play tennis or badminton for ≥3 hours/week. If you frequently perform heavy gardening, you also belong to this group.” (iv) “You take part in competitive sports, swim, play European football, handball or run long distances regularly ie, several times/week.” In the statistical analyses, group 1 is referred to as “low” and group 2 as “moderate”; since only 0.4% belonged to group 4, groups 3 and 4 were pooled and referred to as “high”.

Clinical and health-related factors

Body mass index (BMI)

Based on height and weight measurements, BMI was calculated as body weight in kilograms by height in meters squared (kg/m2).

Blood pressure

Measurements of blood pressure were carried out with the subject seated and after ≥5 minutes rest. A 12-cm wide, 26-cm-long cuff was firmly and evenly applied to the subject’s right upper arm with the lower edge of the cuff placed 2 cm antecubitally. Diastolic blood pressure was recorded at the point where the Korotkoff sounds disappeared (phase 5).

Social class

The men were divided into five social classes according to a system originally elaborated by Svalastoga, later adjusted by Hansen (32, 33). This classification system is based on education level and job position in terms of number of subordinates.

Eligibility

In addition to the 35 men unable to carry out the bicycle test, men with a history of myocardial infarction (N=74), angina pectoris (N=165) or intermittent claudication (N=105) were excluded from the prospective study. In total, this latter group comprised 274 men leaving 4943 men for the incidence study. With respect to all variables included, missing values ranged from 0–2.7%.

End-points

Information on death diagnoses within the period 1970–1971 to end of 2001 was obtained from official national registers and may therefore be considered complete. The ICD mortality diagnoses encompassed the International Classification of Diseases, revision 8, (ICD-8): 410–14 and (from 1994) ICD-10: I20–I25.

Statistical analysis

Basic statistical analyses, including Chi-squared analysis (likelihood ratio), analysis of variance, trend test (Kendall’s tau B), and regression analyses, were performed by use of SPSS version 18.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Relative risks were estimated by exp(β), where β is the hazard coefficient for the variable of interest in a Cox’s proportional hazards regression model with the maximum likelihood ratio method. Assumptions regarding the use of Cox’s proportional hazards were met by inspection of the log minus log function at the covariate mean. Confounders included lifestyle factors (smoking, alcohol, and leisure-time physical activity), clinical and health-related factors (BMI, blood pressure, diabetes and hypertension, and physical fitness) and social class because other studies have found them to be related to sleep duration and cardiovascular risk. Cox proportional hazards regression analysis with IHD mortality as outcome was used to obtain a statistical expression for the interdependency of sleep duration and perceived stress (research question 2) and frequency of use of tranquilizers/hypnotics (research question 3). In addition to main effects of the two variables, age, lifestyle factors, and other potential confounders, we included a multiplicative interaction term between sleep duration (3 levels) and the variables depicting either perceived stress (no pressure, pressure at either work or leisure, pressure at both work and leisure) or use of tranquilizers/hypnotics (never, rarely, regularly). For all analyses, a two-sided probability value of P<0.05 was a priori taken as significant.

Results

In the eligible study population of male employees without history of myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, or intermittent claudication, 587 died (11.9%) from IHD during the period 1970–1971 to 2001. During the same period, 2663 (53.9%) died in total.

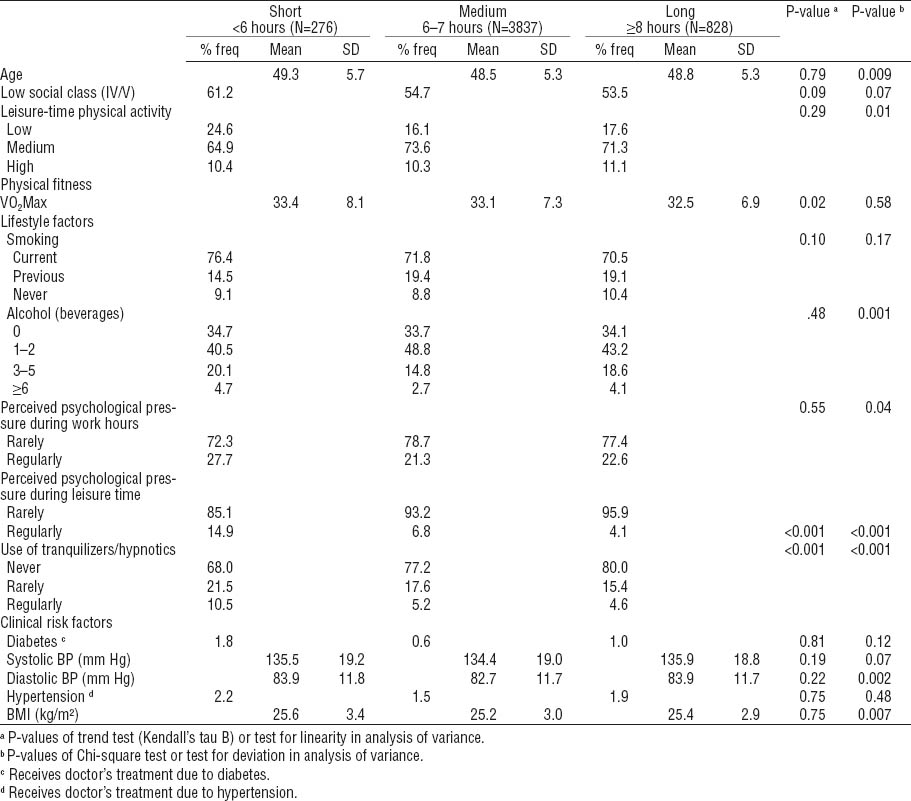

Table 1 illustrates lifestyle and other characteristics according to self-reported daily sleep duration among men without history of myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, or intermittent claudication. Long sleep duration was associated with slightly lower VO2Max, less psychological pressure during leisure time, and more seldom use of tranquilizers/hypnotics. Male workers sleeping 6–7 hours were slightly younger, were more physically active during leisure time, perceived less psychological pressure during work hours, and drank less alcohol. They also had lower diastolic blood pressure and lower BMI than male workers, who slept <6 or ≥8 hours. No significant associations were observed between levels of sleep duration and social class, smoking status, diabetes, systolic blood pressure, or hypertension.

Table 1

Lifestyle and other characteristics in 1970–1971 according to self-assessed daily sleep duration among men without history of myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, or intermittent claudication. [% freq=frequency in percent; SD=standard deviation; VO2Max= maximal oxygen consumption; BP=blood pressure; BMI=body mass index.]

Analysis of correlations between use of tranquilizers/hypnotics and sleep duration showed that 19% of those not using tranquilizers/hypnotics reported exposure to work stress; among rare and regular users of tranquilizers/hypnotics, 27% and 44%, respectively, reported exposure to work stress. Corresponding figures with respect to psychosocial stress during leisure time were 5%, 10%, and 25%.

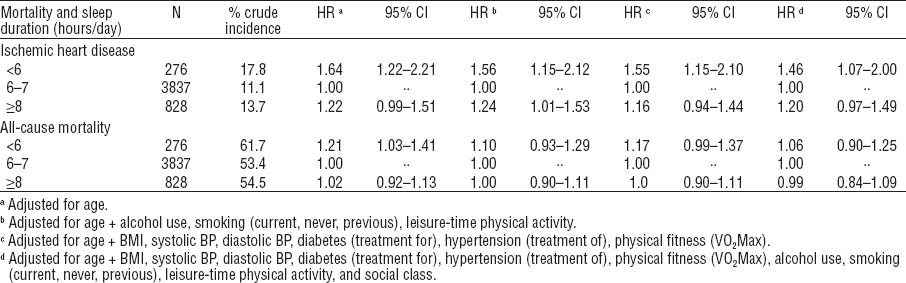

In table 2, the results of Cox proportional hazard regression analysis for associations between sleep duration and IHD and all-cause mortality, respectively, are presented. Short sleep duration (<6 hours) was associated with the highest risk of IHD mortality expressed as hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) when using medium sleepers as the reference group even when adjusting for all confounders (HR 1.46, 95% CI 1.07–2.0). No significant associations were found between sleep duration and all-cause mortality.

Table 2

Number of hours sleep and risk of ischemic heart disease and all-cause mortality 1970–1971 to end of 2001. Different adjustment criteria are applied in Cox proportional hazards regression analyses with forced entry of variables. [HR=hazard ratios; 95% CI=95% confidence interval; BMI=body mass index; BP=blood pressure; VO2Max=maximal oxygen consumption]

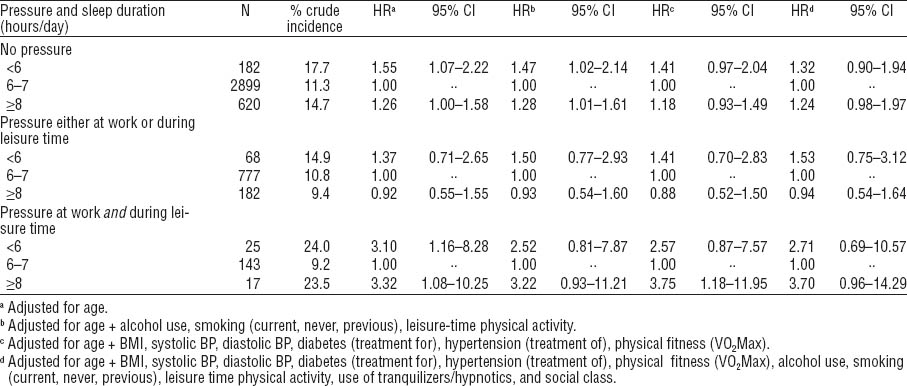

Table 3 shows the results of the Cox proportional hazard regression analysis for associations between number of hours sleep and risk of IHD mortality within groups stratified according to self-assessed psychological pressure during work and leisure. Among men reporting no pressure, short sleepers had an increased risk when adjusting for age and lifestyle only. When adjusting further for clinical factors like BMI, blood pressure, and diabetes, and also use of tranquilizers/hypnotics and social class, the significance disappeared. Among men with perceived psychological pressure either at work or during leisure time, no significant associations were observed between sleep duration and IHD mortality. This was the case also among men reporting pressure at work as well as during leisure time when adjusting for age plus other factors. A tendency of a higher risk was seen among a small group of men (N=17) with long sleep duration when controlling for clinical factors only, an observation with little impact due to the small number in the analysis.

Table 3

Number of hours sleep and risk of ischemic heart disease mortality 1970–1971 to end of 2001 according to self-assessed psychological pressure during work and leisure. Different adjustment criteria are applied in Cox proportional hazards regression analyses with forced entry of variables. [HR=hazard ratios; 95% CI=95% confidence interval; BMI=body mass index; BP=blood pressure; VO2Max=maximal oxygen consumption]

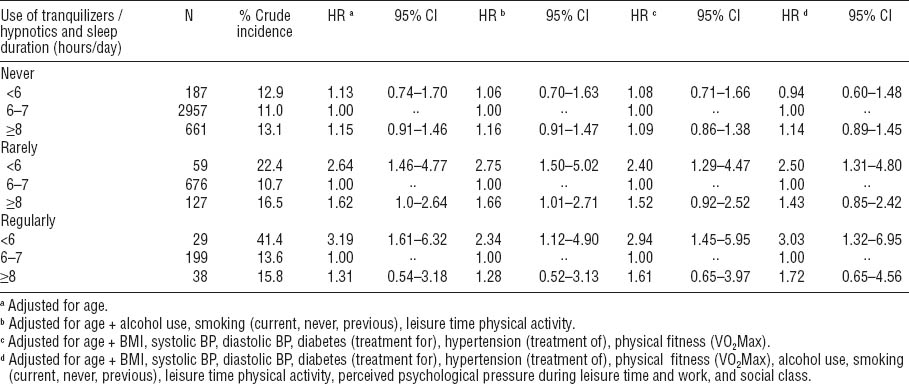

Table 4 shows the results of the regression analyses for the association between number of hours sleep and risk of IHD mortality according to the use of tranquilizers/hypnotics. Among men who reported never having used tranquilizers/hypnotics, no association was found between sleep duration and risk of IHD death. Among men using tranquilizers/hypnotics rarely, an increased risk of IHD death (HR 2.50, 95% CI 1.31–1.84) was observed for short sleepers, referencing medium sleepers when adjusting for all confounders in the analysis. This was the case also for short sleepers who were regular users of tranquilizers/hypnotics (HR 3.03, 95% CI 1.32–6.95) when controlling for all confounders. Among men with long sleep duration, when adjusting for all confounders, no significant associations were found between sleep duration and IHD mortality risk among neither rare nor regular users of tranquilizers/hypnotics.

Table 4

Number of hours sleep and risk of ischemic heart disease mortality 1970–1971 to end of 2001 according to use of tranquilizers/hypnotics: never, rarely, and regularly. Different adjustment criteria are applied in Cox proportional hazards regression analyses with forced entry of variables. [HR=hazard ratios; 95% CI=95% confidence interval; BMI=body mass index; BP=blood pressure; VO2Max=maximal oxygen consumption]

Additional analysis

As described in the statistics section, we performed a final formal analysis testing the interaction of sleep duration and frequency of tranquilizer use as a risk factor for IHD mortality. The interaction was significant on the 0.05 level, whereas neither sleep duration nor tranquilizer use alone could uphold statistical significance as independent risk factors.

Discussion

In this large prospective study, overall we found that men who slept <6 hours had an increased risk of IHD mortality, when referencing those sleeping medium length (ie, 6–8 hours). When controlling for age only, some excess risk for all-cause mortality was also found for short sleepers, but not when controlling for other potential confounders. We therefore focused on IHD mortality. Perceived psychological pressure during work and leisure time was not a significant effect modifier for the association between sleep duration and IHD mortality. In contrast, among men using tranquilizers/hypnotics, whether rarely or regularly, short sleepers had a two to three fold increased risk of IHD mortality, compared to medium sleepers. Among those never using tranquilizers/hypnotics, no association was observed between sleep duration and IHD mortality.

Large individual differences in sleep duration exist (34), and although disturbed or short sleep is a well-known symptom of stress (35), short sleep is not necessarily perceived as non-restorative (36). Users of hypnotics must be assumed to experience negative consequences of short sleep severe enough to seek medical care. Furthermore, a quite strong association between perceived stress and use of tranquilizers/hypnotics was observed in the present study. Together this may reflect that men using tranquilizers/hypnotics are more psychologically stressed and experience less restorative sleep than men exclusively reporting being stressed or sleeping a short number of hours. If this interpretation is valid, our findings suggest that short sleep duration (as a measure of non-restorative sleep) alone is a risk factor for IHD mortality, and the effect is increased when short sleep duration is combined with use of tranquilizers/hypnotics (as a potential measure of stress). This fits very well with psychophysiological effort–recovery theories (23, 24), the theory of allostasis (25, 26) and the cognitive activation theory of stress (27). The theories underline the combination of prolonged or repeated stress and insufficient recovery in the development of disease.

It should be noted that tranquilizers/hypnotics in themselves may have physiological side effects associated with an increased risk of IHD (37). Use of hypnotics alone has been found to be associated with an increased mortality risk in previous studies, even among infrequent users of these drugs (8, 38, 39). We are aware of only one study which has investigated the interaction effects of sleep duration and hypnotics as risk indicators for IHD mortality (14). In contrast to our findings, Suzuki et al (14) found no effects of short sleep duration on CVD mortality among Japanese elderly residents with insomnia or use of hypnotics. The use of tranquilizers and hypnotics could theoretically induce metabolic changes either directly or via lifestyle changes, in particular a reduced physical activity level increasing the risk of IHD mortality. However, this explanation seems unlikely since in our study no association was found between the use of tranquilizers/hypnotics and IHD mortality among men with medium or long sleep duration.

The potential mechanisms by which extreme sleep habits may affect IHD mortality are not clear. However, short-term sleep deprivation has been associated with several adverse physiological changes, eg, reduced glucose tolerance, increased sympathetic nervous activity, and activation of pro-inflammation pathways in experimental studies (18, 19). In the present study, we observed associations between sleep duration and specific mortality in terms of IHD mortality, but not all-cause mortality after adjustment for potential confounders. That sleep duration is associated with certain causes of death, but not others, suggests that specific pathways exist between sleep duration and cardiovascular mortality. The identification of specific pathways implies that (changes in) sleep duration has specific pathophysiological effects, rather than just being a marker of poor health or a clustering of other risk factors.

Strengths and limitations

Basic methodological challenges confronting the researcher in an epidemiological observational study include temporality, good validity of the exposure and outcome, and a sufficient confounder control. The present study fulfills the first and the latter challenges, and also the quality of the outcome measure must be considered sufficient, since the Danish national registers have been shown to have a high validity (40, 41). The present study relies on self-reports of sleep duration rather than objective measures. However, answers to a questionnaire addressing habitual sleep may in fact be a more relevant measure in a prospective epidemiological study than an objective measurement (eg, actigraphy performed over a limited time period). Furthermore, self-assessed sleep duration proves its internal validity by showing its capacity to discriminate subjects with different lifestyles and other characteristics as well as mortality risk. Sleep duration was reported in a priori fixed categories, which made the assessment cruder than if reported as a continuous variable. Furthermore, the categories may not be optimal. As an example, those sleeping 6 hours, who may have somewhat increased risk, are included in the mid-range sleepers and thereby increase the risk in the reference group; those sleeping 8–9 hours are included with the long sleepers and thereby decrease the risk in this group. The consequence of the potential misclassification of medium and long sleep would be an attenuation of the risk associated with long sleep duration, and may thus, at least to some degree, explain the lack of association between long sleep duration and mortality in the present study. Also the question asked on use of tranquilizers and hypnotics did not allow us to pin-point the indication for which the medicine was given. Still, both drugs are markers of subjective psychological stress. When interpreting the results it should be remarked that the baseline of the present study was carried out in 1970–1971 and there have been some changes in the type of drugs used as tranquilizers/hypnotics, which could potentially affect the results. During the 1970s there was a decrease in the sale of barbiturates and sedative–hypnotics, while the sale of benzodiazipines increased (42). During the 1990s, benzadiazipines have to some degree been replaced by z-hypnotics (eg, zaleplon and zolpidem). Although there are differences in the chemical structures, they both act as benzodiazepine receptor agonists and therefore initiate similar pathways (43). The study population of the Copenhagen Male Study is urban Danish male workers between 40–59 years of age in 1970–1971. The findings of this study should therefore be tested by other researchers and in other cohorts eg, females, younger workers, self-employed or workers from other (eg, rural) communities and of other nationalities.

Concluding remarks

The results of the present study show that short sleep duration is a risk factor for IHD mortality only among middle-aged and elderly men, particularly those using tranquilizers/hypnotics on a regular or even a rare basis, but not among men not using tranquilizers/hypnotics. Although a strong association was observed between perceived stress and frequency of tranquilizer use, no clear interplay was found between sleep duration, self-assessed psychological stress, and risk of IHD mortality.

Competing interest statement

All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organization for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical considerations statement

When the Copenhagen Male Study was initiated as a closed cohort study in 1970–1971, no ethics committee for medical research had been established in Denmark. However, in 1985–1986, when survivors from the first baseline were re-examined, the study was approved by the ethics committee for medical research in the county of Copenhagen, and all participants in the study gave informed consent to participate, as stated in many previous publications from the Copenhagen Male Study based on analyses using the 1985–1986 baseline.