With ever increasing traffic volumes and urbanization, road traffic noise is already one of the most common environmental nuisances globally. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends noise levels of <50 decibels (dB) and <40 dB at day- and night-time, respectively, to limit public disturbance (1, 2). More recently, to identify populations exposed to high noise levels, the European Commission required environmental noise maps for urban areas with populations of >100 000 persons and roads with >3 million vehicles per year (3). Based on these noise maps and other estimates, even in scarcely populated Finland, nearly one fifth of the population is exposed to road traffic noise levels >55 dB (4).

The WHO has estimated that more than a million healthy life years are lost due to traffic noise in Western Europe (5). Epidemiological studies have reported associations between road traffic noise and cardiovascular health, but the possible confounding by air pollution from traffic has often not been taken into account (6). Associations have been reported also between noise and eg, sleep problems (7–9), annoyance (10, 11) and decreased health-related quality of life (12). Further evidence suggests that aircraft noise is associated with poor self-rated health and generalized anxiety disorder (13, 14), and decreased children’s cognitive performance (15, 16). However, only a few studies have looked at associations between road traffic noise (a more common environmental nuisance than aircraft noise) and self-rated health (8) or psychotropic medication use (eg, hypnotics) (17–19) among adults, and even fewer have studied how noise-sensitivity affects these associations (20).

In this study, we examined whether traffic noise is associated with self-rated health and register-based psychotropic medication use. More than 15 600 men and women participated in the study and were blind to its aim. We also stratified the analyses by trait anxiety as the associations may be stronger in population groups sensitive to noise (7).

Methods

Study population

Participants of the Finnish Public Sector Study, an on-going prospective study among employees of ten towns and six hospital districts, provided the basis for the study population. The sex and age distribution of the whole cohort is representative of Finnish public sector employees (75% women in this cohort versus 77% women in the public sector; mean age of all participants 44 versus 45 years, respectively), and the participants cover a wide range of occupational groups. Surveys were mailed to all current employees at the participating organizations in 2000, 2004 and 2008, as well as in 2005 and 2009 for those participants who completed questionnaires while employed, but thereafter had left the participating organization (response rate 69%). Coordinate data of the participants’ residential addresses and the dates of moves (at the level of street name and number) between 2000 and 2010 were obtained from the Population Register Center and the address at the time of the survey was used for the modeling. The modeled traffic noise levels were available for the cities of Turku, Helsinki and Vantaa, and thus cohort participants living in these cities were included in this study. The final sample was 15 611 men and women. The ethics committee of the Hospital District of Helsinki and Uusimaa has approved the Finnish Public Sector study, including this work.

Assessment of road traffic noise levels

For each participant, we used data from the study year that was chronologically the closest to the noise modeling period (ie, 2011 in Turku, 2006 in Helsinki, and 2005 in Vantaa). Because of the variation in the modeling periods, the modeling was done before the survey for some participants and after for others. The difference between the survey and noise modeling years was on average 3.2 years. The exposure variable was road traffic noise level (Lden), which is the average value of the annual noise level with weighting factors of 5 dB(A) for the four-hour evening period, and 10 dB(A) for the eight-hour night period. Noise levels in the cities of Turku (21), Helsinki (22) and Vantaa (23) were modeled for major highways and the main and collector streets using the Nordic prediction methods (24), 10 m grid size, and calculation height of 4 m. Temporal variation of traffic intensity was automatically measured by a traffic monitoring system at several main and collector streets in all three cities. Smaller streets that had no data on traffic intensity were excluded from the noise model. First order reflection and the effect of noise barriers were included in the noise calculations. Data resolution was 0.1 dB.

We linked the modeled noise levels to the survey data using the coordinates of the exposure points and the residential addresses of participants. Noise levels at the most exposed façades of residential buildings were estimated using ArcMap 10 (Esri, Redlands, CA, USA). First, we removed all noise grid points on top of buildings. Then, two closest noise grid points within a 20 m buffer around the residence coordinates were identified for each residence and the higher of these points was selected to represent the noise exposure. For the analyses, we categorized traffic noise into five classes: ≤45 (reference, number of participants=2821), 45.1–50 (N=4110), 50.1–55 (N=3597), 55.1–60 (N=2445), and >60 dB (N=2638) (7).

Assessment of outcome variables

The respondents assessed their health status on a 5-point scale (1=very good, 2=good, 3=average, 4=poor, 5=very poor). This measure was dichotomized and used as an indicator of poor self-rated health (average/poor/very poor versus good/very good). This is one of the most widely used measures of health status (25), shown to be related to a number of important medical endpoints and sensitive to changes in health status (26, 27).

For psychotropic medication use, individual-level information on the dates of filled outpatient prescriptions was obtained from the National Prescription Register, managed by the Social Insurance Institution of Finland (28). The national sickness insurance scheme covers the entire population, regardless of age or occupational title, and provides reimbursement for all filled prescriptions. Based on the WHO Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification codes (29), we chose anxiolytics (N05B), hypnotics (N05C), and antidepressants (N06A) to determine a summary variable for psychotropic medication use (yes versus no) during the year of the survey, as in a prior study (30).

Assessment of trait anxiety

Anxious people are vigilant to the potentially threatening aspects of the environment (31) and may therefore be particularly sensitive to noise. As in our prior study (7), we used a trait anxiety score as an indicator of noise sensitivity. The score was derived from a 6-item trait anxiety inventory (a short version of the 20-item Spielberger trait anxiety inventory) (32) about how the person generally feels (“I feel calm”, “I am relaxed”, “I feel satisfied”, I feel tense”, “I feel upset”, “I am worried”; all items are rated on a 4-point scale: “not at all=1”, “a little=2”, “to some degree=3”, “very much so=4”). When responses to≥4 of the 6 questions were available, we calculated the mean value of these points to get the trait anxiety score (reverse scaling used for “I feel calm”, “I am relaxed”, and “I feel satisfied”). Values higher than mean indicated “high trait anxiety score”.

Individual-level covariates

Age, sex, and socioeconomic status (SES) can be significant confounders of the association between traffic noise and health (8). We obtained information on age, sex, and occupational titles of the participants from the employers’ registers. Occupational status was used as an indicator of individual SES and categorized into three groups (high=upper grade non-manual workers, intermediate=lower grade non-manual workers, and low=manual workers) based on Statistics Finland’s Classification of Occupations (33). Other proxies for individual SES were the level of education (high=university degree, intermediate=high school or vocational school, low=comprehensive school) obtained from Statistics Finland, and size of apartment (high>100, intermediate= 70–100, low<70 m2) from the Population Register Center.

Information on other possible confounders, such as work stress and lifestyle factors, was obtained from the surveys: job strain [high demand and low control (34)], smoking status (current smoker versus non-smoker), leisure-time physical inactivity [<2 metabolic equivalent task hours per day, ie, approximately 30 minutes brisk walking per day (35)], obesity [body mass index (BMI) ≥30 versus <30 kg/m2], and heavy alcohol consumption [≥24 drinks/week for men, ≥16 drinks/week for women (36)].

We also collected data on chronic somatic illnesses from the Drug Reimbursement Register of the Social Insurance Institution of Finland (37) to build a “chronic disease” indicator (yes versus no). The register contains individual-level information on entitlements to special reimbursement for the cost of medication for chronic illnesses (hypertension, cardiac failure, ischemic heart disease, diabetes, asthma or other chronic obstructive lung disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and severe mental disorders), and the date of reimbursement. Data on cancer diagnoses, obtained from the Finnish Cancer Registry, was also used to build the indicator (38).

Area-level covariates

Because both traffic noise levels and health status have been found to vary by area-level SES (39, 40), we obtained area-level socioeconomic variables from the grid database of Statistics Finland (41). An index for area-level socioeconomic disadvantage was calculated for each 250×250 m map grid (“a neighborhood”) using information on the median household income, level of education, and unemployment rate (42). As a proxy for the degree of urbanization in the neighborhood, we used population density that was calculated by dividing the total number of residents within each map grid by the surface area of the map grid (inhabitants/km2).

Statistical analysis

Logistic regression models for the categorized exposure (GENMOD procedure of SAS 9.3, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) were used to study associations between noise and the dichotomized outcome variables as well as possible trends and curvilinearity in these associations. All analyses were stratified by sex because the association may vary by sex and also because the analytical sample was female dominated (80% women). Models were first run without adjustments (Model 1) and then adjusted for age, marital status, individual-level SES variables, job strain, chronic disease, area-level SES, and population density (Model 2). Those participants with missing data were excluded from the analyses. The models were then stratified by trait anxiety to examine whether associations were different among those likely to be more sensitive to noise.

In further analyses, we adjusted the models for the following lifestyle risk factors: smoking, heavy alcohol use, physical inactivity, and obesity. A separate analysis was run using noise categorization: ≤45, 45.1–50, 50.1–55, 55.1–60, 60.1–65, and >65 dB, although the number of those exposed to the highest noise level (>65 dB) was low (men=267, women=949). We also ran the models including only those who had lived in the address of the survey date for ≥3 years (N=12 336) and models for the medication use by individual medications.

Results

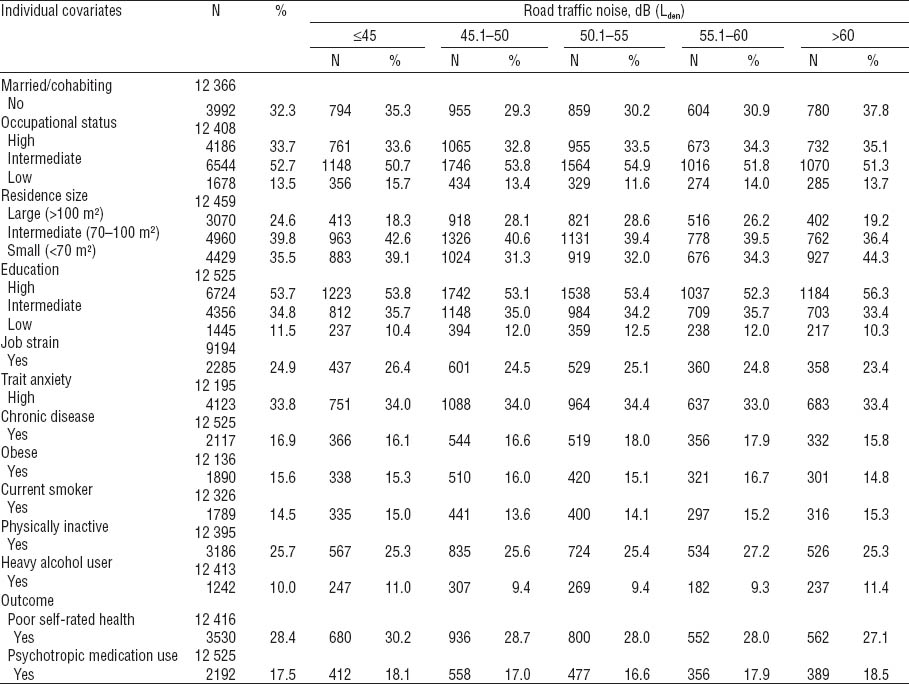

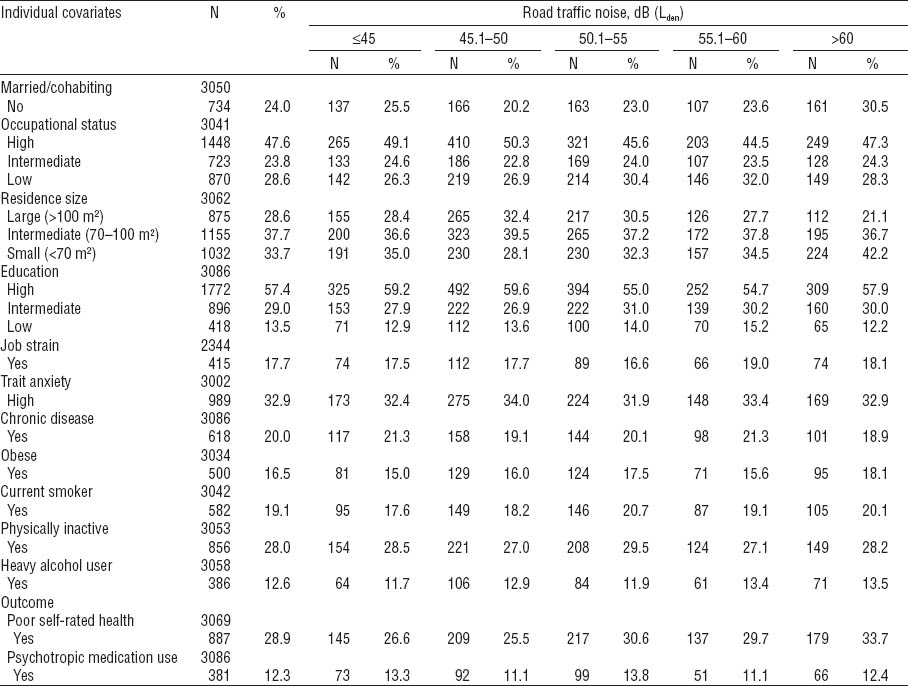

The mean age of the 15 611 study participants was 50.3 (range 21–76) years. The mean noise level at the residential address was 52 dB (standard deviation 8.1, range 18–79 dB). Of the participants, 4417 (28.3%) had poor self-rated health and 2573 (16.5%) had purchased any psychotropic medication [1617 (10.4%), antidepressants, 592 (3.8%) anxiolytics, and 1152 (7.4%) hypnotics]. Detailed description of the study population by sex and categorized noise levels is provided in tables 1 and 2.

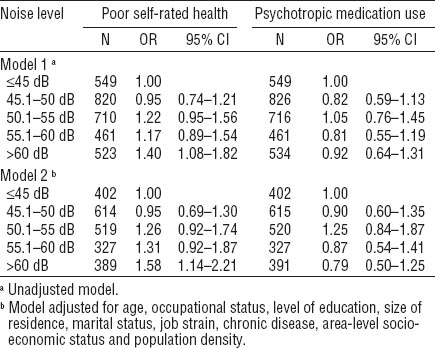

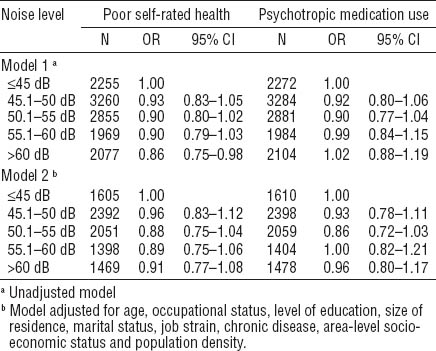

After adjustment for age, occupational status, level of education, size of residence, marital status, job strain, chronic disease, area-level socioeconomic status and population density, a statistically significant association was observed between noise >60 (versus ≤45) dB and poor self-rated health among men (table 3). There was also evidence of linear trend for this association (test for trend P<0.01), and no evidence of curvilinearity (test for trend P>0.05). No associations were observed for psychotropic medication use (table 3). Among women, no significant associations were observed in the adjusted models for either of the outcomes (table 4).

Table 3

Odds ratios (OR) for associations of road traffic noise (Lden) with poor self-rated health and psychotropic medication use among men. [95% CI=95% confidence interval]

Table 4

Odds ratios (OR) for associations of road traffic noise (Lden) with poor self-rated health and psychotropic medication use among women. [95% CI=95% confidence interval]

In the analyses stratified by noise sensitivity as indicated by trait anxiety score, the association between noise at the highest level and poor self-rated health among men was more pronounced among those reporting a high anxiety score in Model 2 (table 5). The stratification did not reveal associations for traffic noise and psychotropic medication use among men or for traffic noise and the two outcomes among women (data not shown).

Table 5

Odds ratios (OR) for associations of road traffic noise (Lden) with poor self-rated health among men by trait anxiety score. [95% CI=95% confidence interval]

Further adjustment for smoking, heavy alcohol use, physical inactivity and obesity had little effect on the association found for men (OR 1.51, 95% CI 1.06–2.16 for >60 versus ≤45 dB); no associations were observed for women (data not shown). Although the number of those exposed to the higher noise levels (60–65 and >65 dB) was low, exposure to 60–65 versus ≤45 dB (OR 1.52, 95% CI 1.02–2.27) and exposure to >65 versus ≤45 dB (OR 1.66, 95% CI 1.10–2.49) were associated with poor self-rated health among men but not women. In the analyses restricted to those who had resided in the same address ≥3 years, the association in the highest noise category (>60 dB) was strengthened with the adjusted OR being 1.90 (95% CI 1.30–2.78) among all men. For individual medications, no associations were observed (data not shown).

Discussion

In this study, exposure to road traffic noise >60 compared with ≤45 dB was associated with an increased risk of poor self-rated health among men, particularly those with high trait anxiety, but not among women. We found no evidence to suggest that traffic noise would be associated with register-based use of psychotropic medication.

Our findings for men are in agreement with a recent study on Swiss people, which indicated that traffic noise is associated with self-reported health status, although they did not report sex-specific results (8), and with a study showing aircraft noise at 50 dB (Lden) to be related to poor self-rated health among those living within 25 km of an airport (14). In one of the earlier works, acute health symptoms (eg, irritability and difficulty getting to sleep) were more commonly reported among those living in areas of aircraft noise levels of ≥45 dB compared to <45 dB (43). Another study found associations between perceived street noise and physical and mental dimensions of health-related quality of life (12), but as the street noise was measured with self-reports the finding may be attributable to reporting bias or common methods bias, both artificially inflating associations. Chronic illnesses, lack of physical exercise, and psychological distress, for example, are shown to lead to weakened self-rated health (44, 45). Mechanisms of the effect of noise on self-rated health are not known, but in principle all these pathways may be relevant: traffic noise has been associated, for example, with chronic cardiovascular diseases, decreased willingness to go out walking, and increased stress reactions (12, 46, 47).

The use of psychotropic medication, including anxiolytics, hypnotics, and antidepressants, was not associated with noise levels. These findings agree with the HYENA study reporting no association between traffic noise and use of anxiolytics (17), although in that study there was an association between aircraft noise exposure and use of anxiolytics. Two other studies have assessed associations between night-time traffic noise and sleep medication use but reported conflicting results (18, 19). In a subset of our cohort, we previously found night-time traffic noise levels to be associated with sleep disorders especially among persons with higher scores for trait anxiety (7). The lack of association with hypnotics in the current analyses may be due to lack of power as only 5.9% of men and 7.7% of women had purchased hypnotics. It is also possible that the subjective health problems, as indicated by poor self-rated health and sleep disturbances (in our previous study), have been mild and below the threshold to seek medical aid [the different noise metrics used in our previous (Lnight) and this (Lden) study were highly correlated with Pearson correlation coefficient 0.99]. Furthermore, we did not have data on traffic noise exposure levels indoors, where people spend most of their time. In Finland, the indoor noise levels are clearly lower than the outdoor levels because of the good residential building structures such as triple glazed-windows (48) (the minimum requirement is double-glazed).

We found a sex-specific association in relation to poor self-rated health. Noise may be differently perceived by sex; however, others have shown that traffic noise annoyance is more commonly reported by women than men (49), and we have shown that the association between night-time traffic noise and sleep problems may be more pronounced among women than men (7). Both of these findings indicate sex differences opposite to those observed in this study. A further potential explanation involves the specific health outcome (self-rated health). Although perceived health is likely to be reported equally reliably by men and women (50), some studies have shown that self-rated health may be a better predictor of severe health outcomes, such as mortality, among men than women (27, 51). This is possibly due to a higher threshold for reporting poor health among men than women, and suggests that perceived health may reflect different components of physical and mental health among men and women.

Further analyses revealed that the associations between noise and self-rated health were present only among men who reported higher trait anxiety scores. In a large number of studies road traffic noise has been related to annoyance (10, 11). Annoyance ratings to traffic noise have further been linked to trait anxiety (52), and thus, personality disposition, such as trait anxiety, may act as a moderating factor in the health effects of noise. We have previously reported night-time traffic noise to be associated with sleep disorders more strongly among those with trait anxiety (7). This suggests that anxiety does not increase the effect of noise on health only through conscious mental processes such as annoyance. Further research is needed to recognize other personal characteristics that may increase the individual’s vulnerability to the effects of road traffic noise.

The following limitations should be considered when interpreting these findings. First, we had limited data on area-level confounders. Therefore, we could not evaluate to what extent traffic noise acts as an indicator rather than a causal factor for poor environment (eg, lack of green space, poor air quality, and unsafe neighborhood). Although most requirements for the modeling of road traffic noise were the same in the three cities, some differences in the modeling existed. However, noise modeling always includes some uncertainty and it is likely that these differences had only a minor effect on the study results. Some imprecision in the current noise modeling is due to the lack of information about traffic intensities on small streets. As the data were cross-sectional, interpretations of the causality of the associations cannot be made. Further, as most participants supposedly spend on average 8–9 hours on a week day at work and commuting, noise exposures away from home may have affected the results. However, high noise exposure at work, for example, could have biased the observed associations only if high occupational exposure would have been associated with high noise exposure at home. The generalizability of these findings to other countries may also be limited because of the building characteristics, which leads to different indoor noise levels. Due to harsh climate in Finland minimum of double windows are required for all residential buildings, for example, and keeping windows open is less frequent especially during the cold season (53).

Despite these limitations, our study, where the participants were blind to the aim of the study at the time of the surveys, provides important population-level evidence to suggest that traffic noise levels >60 dB are associated with poor self-rated health among employed men, particularly those with higher trait anxiety scores. However, the perceived decline in health status did not lead to increased use of medication, indicated by the absence of associations between traffic noise and psychotropic medication use. Future research should evaluate the biological and psychological mechanisms linking traffic noise exposure with weakened self-rated health and the further medical consequences of the effect.