Due to increasing competition in the global market, the number of precarious workers has been increasing worldwide (1–4). Previous studies have reported that temporary workers perceive job insecurity more frequently than full-time permanent workers (5–7). Employment instability is associated with psychological problems (7–9). The effect of precarious employment on mental health has been analyzed in previous studies, mostly in Europe and North America (1, 7, 10). A few cross-sectional studies have reported an association between precarious employment and mental health in East Asia (11, 12). However, their cross-sectional study design could not exclude reverse causation between precarious employment and depressive symptoms (13). Longitudinal studies dealing with precarious employment and depressive symptoms in East Asia are scarce. A recent longitudinal study in Japan showed that precarious employment in a developed country was associated with serious psychological distress during the 4-year follow-up period (3). As for developing countries in East Asia, one study in South Korea showed that a change from permanent to precarious work was associated with the development of depressive symptoms during a 1-year follow-up period (2). Previous longitudinal studies in developing countries concerning precarious employment and depressive symptoms are scarce and have a relatively short follow-up period, if any. Furthermore, employment status in developing countries is not as stable as in developed countries such as Japan. There have been previous studies on the effect of sex (2, 3, 11, 14), but despite the importance of the psychological burden of being head of household, none of those studies stratified by head of household status. Whether a basis of precarious employment is voluntary or involuntary might be an important factor for depressive symptom, we used being head of household as proxy variable for willingness to be a precarious worker.

The purpose of our prospective study was to examine the impact of employment status and its changes in employment status on the development of new-onset severe depressive symptoms, stratified by sex and head of household status, using nationally representative longitudinal data collected from 2007–2013 in South Korea.

Methods

Study sample and dataset

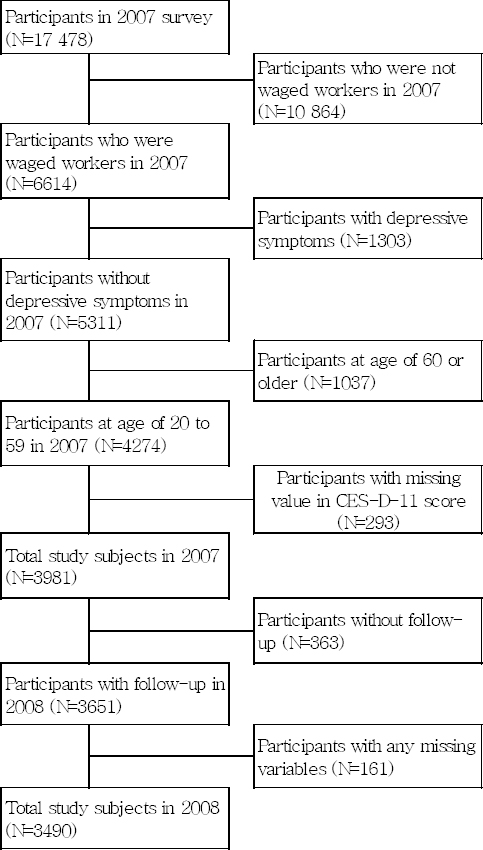

The data used in this study were from the Korean Welfare Panel Study (KOWEPS) 2007–2013. The KOWEPS, conducted by the Korean Institute of Social and Health Affairs in conjunction with the Social Welfare Research Institute of Seoul National University, is an ongoing longitudinal study of a nationally representative sample of Korean households; data is collected annually (www.koweps.re.kr) (15). Trained interviewers conducted face-to-face interviews at the participants’ households using structured questionnaires. The 1st wave of KOWEPS started in 2006, but the definition of full-time permanent employment changed in the 2nd wave and was maintained thereafter. This study included data from the 2nd wave in 2007. In the 2nd wave, 17 478 subjects completed the survey questionnaire. The baseline study subjects consisted of waged workers ≥19 years of age who did not have depressive symptoms [Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) score <16]. Subjects aged ≥60 years in 2007 were excluded so that all subjects in this study were <65 years old during the 6-year follow-up. After excluding subjects without follow-up in 2008 or with any missing values, a total of 3490 workers remained in this study (figure 1).

Outcome variable

The dependent variable in this study was development of severe depressive symptoms. To measure depressive symptoms during previous week at the point of interview annually, the KOWEPS used the Korean version of the CES-D 11-item, 4-point (0–3) (CES-D-11) questionnaire, which was developed from the 20-item standard form CES-D (CES-D-20) (16, 17) This short form CES-D is known to be comparable to the CES-D-20 (16, 18). The CES-D-11 score was multiplied by 20/11 to match the CES-D-20 score. A Previous validation study for CES-D-20 in Korea suggested that a cut-off point of 25 was optimal for detecting possible cases of major depressive disorder and a cut-off point of 21 was set as screening tool for identifying subjects with depressive symptoms (19). In Western countries, the score of 16 has been traditionally used as an optimal CES-D cutoff point for determining whether a person has symptoms of depression (20). And in Korea, many studies used 16 as the cut-off point in CES-D-20 for the detection of probable depressive symptoms (21).

Because of different ways of expressing affect, especially the suppression of positive affect in cultures based on Confucian ethics in Korea, a CES-D-20 score of 21 (higher than Western countries) was recommended as the cut-off for a screening tool to detect possible major depressive disorder (19). In this study, CES-D-11 scores of 9 and ≥12 (equivalent to CES-D-20 scores of 16.4 and 21.8, respectively) were the cut-offs for moderate and severe depressive symptoms, respectively.

In this longitudinal study, for the purpose of identifying clinical-level new-onset depressive symptoms among workers with relatively healthy mental status, new-onset severe depressive symptoms was defined as the occurrence of a CES-D-11 score of ≥12 from 2008–2013 in a worker with a CES-D-11 score of <9 at baseline in 2007.

Measurement of employment status

The independent variable in this study was main employment status of last year, measured each year from 2008–2013. Employment status was classified into four categories: full-time permanent, precarious, self-employed, or unemployed. The KOWEPS classified individuals as full-time permanent workers if all four of the following conditions were satisfied: (i) they were directly hired by their employers (not subcontracted or dispatched workers or self-employed workers without employees); (ii) they were full-time workers (not part-time workers); (iii) there was no fixed term in their employment contract (not temporary workers); and (iv) there was a high probability of maintaining their current job (having relatively little job insecurity and not a day laborer) (2). We used the same definition of full-time permanent employment as a previous study done with KOWEPS 2007–2008 data (2). This definition was similar to that used in a previous prospective study in Japan (3). Other than full-time permanent workers, waged workers hired by their employers were classified as precarious workers. The self-employed were defined as workers who managed their own business regardless of scale or carried out professional matter on their own responsibility. For the purpose of comparability with previous East Asian studies and consideration of different classification of employment status between countries, the self-employed were treated as having a different employment status. The unemployed were defined as those who had been waged workers at baseline in 2007 but lost employment by the time of the survey.

The baseline study subjects in 2007 were waged workers whose employment status was full-time permanent, precarious, or self-employed. Because employment status changed frequently, we measured employment status annually, allowing multiple transitions and adding unemployment as a new category. The unemployed consisted of housewives, job seekers, and the economically inactive population.

Additionally, we assessed change in employment status annually allowing multiple transitions to investigate its impact on the development of severe depressive symptoms (2). There were four categories of status change: (i) remaining full-time permanent (remaining permanent); (ii) changing from full-time permanent to another employment status (permanent to non-permanent); (iii) changing from non-permanent to full-time permanent (non-permanent to permanent); and (iv) remaining in non-permanent employment (remaining non-permanent). The non-permanent employment status included the precarious and the unemployed.

Covariates

Various covariates that could be related to employment status and depressive symptoms were selected. All variables were assessed each year, except for occupation and company size. Age in years was a continuous variable. The baseline CES-D-11 score of 0–33 was included to adjust for the effect of baseline depressive mood on future development of severe depressive symptoms. Disposable household income was equalized by dividing it by the square root of the number of household members and then categorized into quartiles before study subject selection each year. The head of household was defined as the actual breadwinner and practical representative of the household, regardless of official record. We divided occupation into two categories: white collar (administrative, professional, clerical) and blue collar (others). Company size was divided into two categories according to the number of employees: ≥30 or <30. Because the unemployed category was added to reflect change in employment status, occupation and company size were assigned the value at baseline in 2007. Exposure to a hazardous working environment was defined by a positive response to the survey question “Have you worked in a hazardous environment or experienced conditions that compromised your safety?” Follow-up years (1–6) were included as a continuous variable. Chronic disease was defined as having taken medicine for ≥6 months. Other covariates included education level, current smoking status, and current alcohol use (22).

Statistical analysis

Because of unique gender roles in eastern Asia and the different structure of the labor market, all analyses were stratified by sex. To determine statistically significant differences between groups, chi-square test was performed to compare categorical variables, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to compare continuous variables. The longitudinal dataset in this study contained one record per observation to reflect repeated measurements. For the identification of new-onset severe depressive symptoms, subjects were censored after the first event of severe depressive symptoms.

Employment status and all other covariates were measured annually and treated as time-dependent variables allowing multiple transitions. With this dataset, we performed a generalized estimating equation (GEE) analysis with exchangeable working correlations to estimate odds ratios for the development of new-onset severe depressive symptoms among precarious workers and the unemployed compared with full-time permanent workers. The association between change in employment status over the last year and development of new-onset depressive symptoms was tested using the same GEE analysis. Then, as a reflection of patriarchal social order in East Asia, GEE analysis was performed, stratified by head of household status and sex.

A sensitivity analysis was performed on a subgroup dividing precarious employment into full-time and part-time non-permanent to avoid heterogeneous nature of the precarious employment. All hypotheses in this study were two sided, and P-values <0.05 were deemed statistically significant. We did all statistical analyses with SAS software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

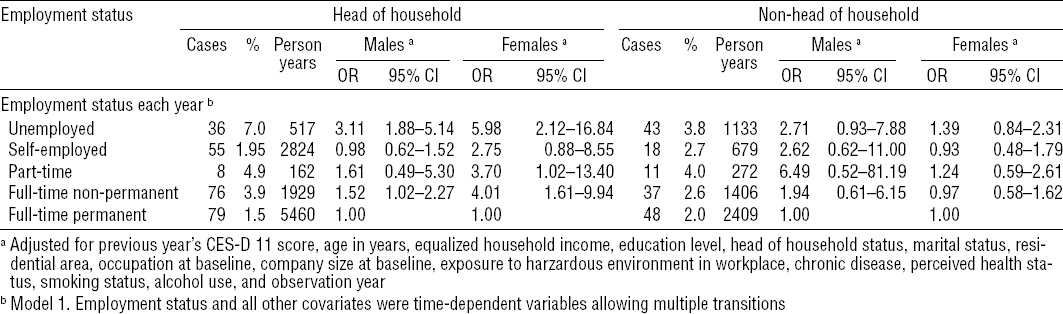

Table 1 shows the general characteristics of the study subjects in 2008, stratified by employment status. Subjects were waged workers at baseline, initially without depressive symptoms. The proportion of full-time permanent workers was 54.2% and 45.4% for males and females, respectively. Among both sexes, precarious workers were more likely to have the following characteristics compared to full-time permanent workers: lower household income, lower education level, lower number of employees in their company, lower levels of exposure to a hazardous environment, lower chronic disease levels, and higher baseline CES-D-11 scores. Baseline CES-D-11 scores were higher among precarious than full-time permanent workers. During the 6-year follow-up period, 229 males (2.1% of person years and 10.3% of subjects) and 168 females (3.0% of person years and 14.3% of subjects) developed new-onset severe depressive symptoms. The retention rate was 77.3% and 79.0% among males and females, respectively; 502 males and 268 females were lost to follow-up.

Table 1

General characteristics at first follow-up (2008) of waged workers without depressive symptoms in 2007.

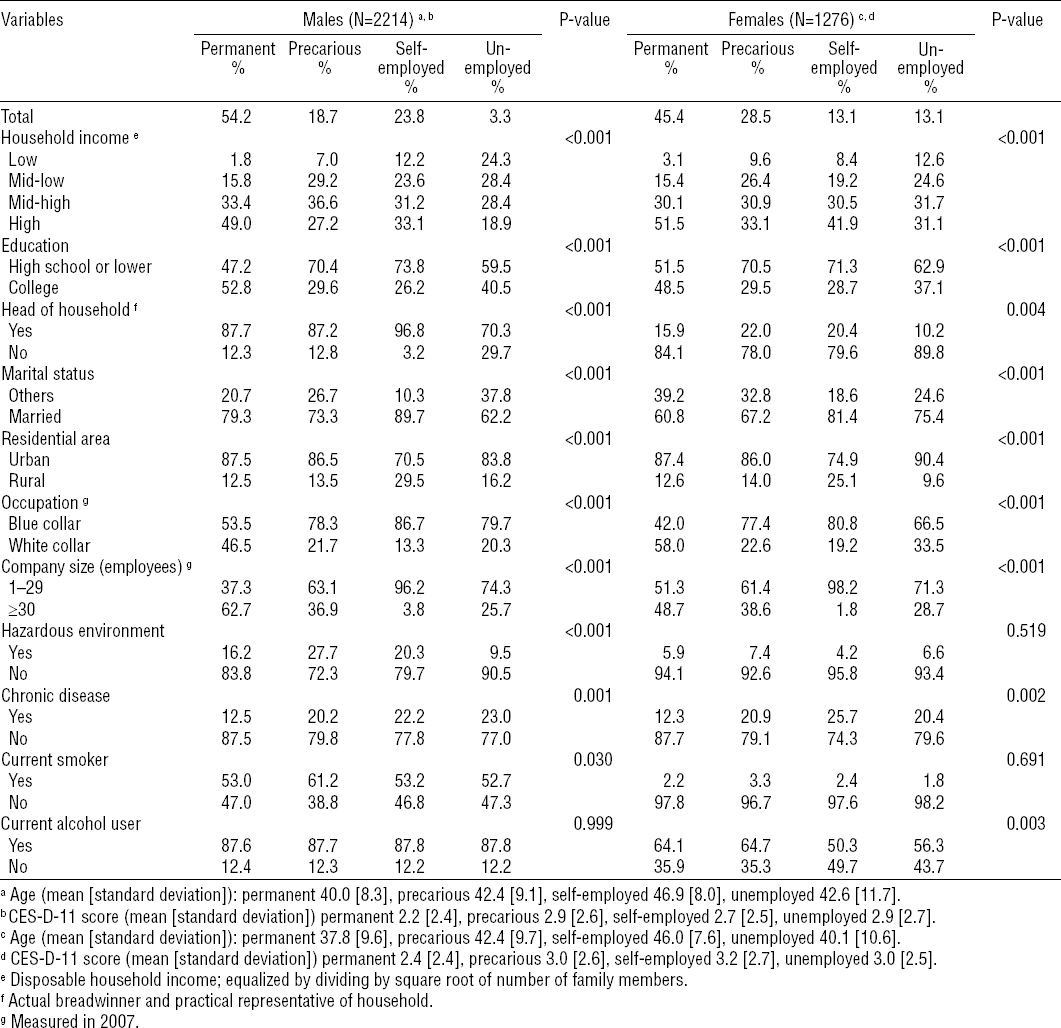

Table 2 shows the odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) resulting from a GEE analysis of the effect of yearly employment status on new-onset severe depressive symptoms during the 6-year follow-up period. Among both sexes, the likelihood of developing new-onset severe depressive symptoms was higher among precarious than full-time permanent workers in the crude model (males: OR 2.28, 95% CI 1.64–3.18; females: OR 1.94, 95% CI 1.33–2.84). After adjusting for all covariates included in this study, OR decreased but remained statistically significant for male workers (OR 1.59, 95% CI 1.10–2.30). Among female workers, statistical significance was not maintained in the fully-adjusted model (OR 1.41, 95% CI 0.94–2.12).

Table 2

Results of a generalized estimating equation analyzing the effect of yearly employment status on new-onset of severe depressive symptoms during the 6-year follow-up period, among individuals who were waged workers at baseline in 2007. Employment status and all other covariates were time-dependent variables allowing multiple transitions. [OR=odds ratio; 95% CI=95% confidence interval]

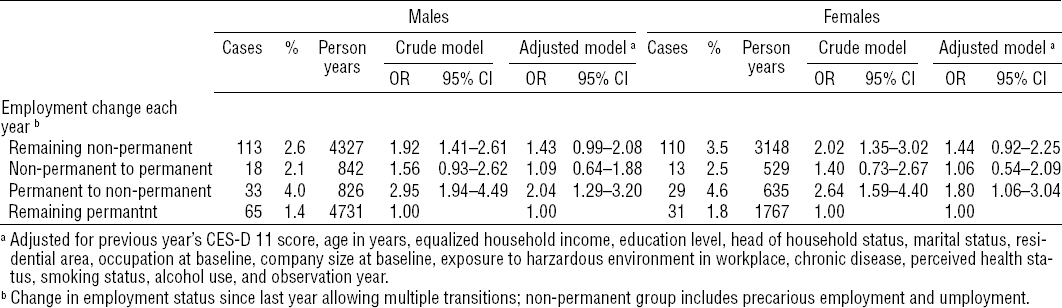

In the fully-adjusted GEE model analyzing change in employment status over the last year (table 3), workers whose employment status changed from full-time permanent to another employment status were more likely to develop new-onset severe depressive symptoms than full-time permanent workers with no change (males: OR 2.04, 95% CI 1.29–3.20; females: OR 1.80, 95% CI 1.06–3.04).

Table 3

Results of a generalized estimating equation analyzing the effect of change in employment status on new-onset of severe depressive symptoms during the 6-year follow-up period, among individuals who were waged workers at baseline in 2007. [OR=odds ratio; 95% CI=95% confidential interval]

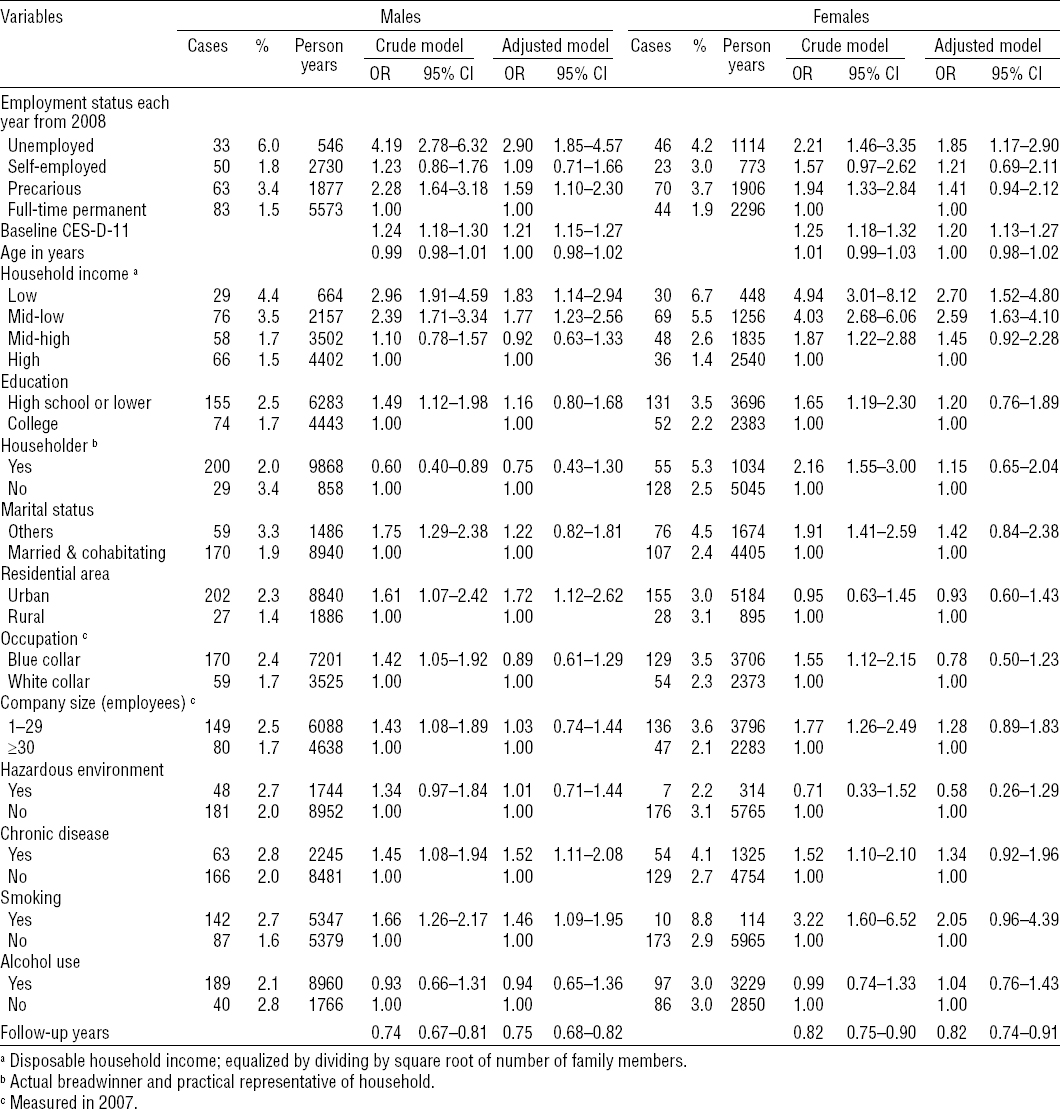

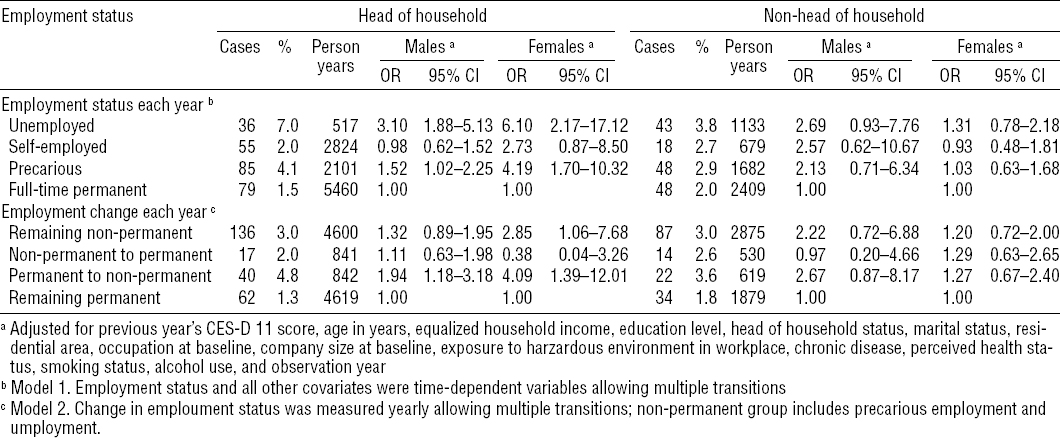

We also performed a GEE analysis of change in employment status stratified by sex and head of household status (table 4). Among heads of household, precarious workers of both sexes were more likely to develop new-onset severe depressive symptoms compared to full-time permanent workers (males: OR 1.52, 95% CI 1.02–2.25; females OR 4.19, 95% CI 1.70–10.32). As for change in employment status, workers who moved from permanent employment to another type of employment were more likely to develop new-onset severe depressive symptoms compared to those remaining in the full-time permanent employment (males: OR 1.94, 95% CI 1.18–3.18; females: OR 4.09, 95% CI 1.39–12.01). Female heads of household who remained in the non-permanent employment were more likely to develop new-onset severe depressive symptoms compared to those remaining in the full-time permanent employment (OR 3.56, 95% CI 1.24–10.21), whereas no significant association was found among male heads of household. A sensitivity analysis showed similar results especially among females (table 5).

Table 4

Results of a generalized estimating equation analyzing the effect of yearly employment status and change in employment status on new-onset of severe depressive symptoms during the 6-year follow-up period, among individuals who were waged workers at baseline in 2007. [OR=odds ratio; 95% CI=95% confidence interval]

Discussion

After adjusting for initial baseline CES-D-11 scores, chronic disease, and other socioeconomic covariates, our 6-year longitudinal study indicates that male precarious workers were more likely to develop new-onset severe depressive symptoms than full-time permanent workers. Among both sexes, a change from full-time permanent to another employment status was associated with the development of new-onset severe depressive symptoms. In particular, head-of-household stratification showed that female heads of household with precarious employment were about 4 times more likely to develop new-onset severe depressive symptoms than female heads of household whose employment status remained full-time permanent.

Previous longitudinal studies suggested that precarious workers were more likely to develop depressive symptom (23) and work disability due to depressive disorders (24). Some studies have reported that the change from permanent to precarious employment is positively associated with the development of new-onset depressive symptoms (2), lower self-rated health status (14), and suicidal ideation (12). Furthermore, some studies have reported that the transition from precarious to full-time permanent employment was positively associated with mental ill-health among females in East Asia (2, 14).

A recent discrete survival analysis performed on a Japanese sample of 50–59 year olds over a 4-year follow-up period demonstrated male precarious workers were more likely to develop serious psychological distress than male full-time permanent workers (hazard ratio 1.79, 95% CI 1.28–2.51), but such an association was not observed among females (3). Although the outcome of the above study was a mood or anxiety disorder and employment status in the baseline survey was treated as a time-independent variable, this result was comparable to our study’s findings in that the association was observed only among males.

As for changes in employment status, a recent longitudinal study reported that new-onset depressive symptoms were strongly associated with a change from permanent to precarious employment (OR 2.88, 95% CI 1.24–6.66) or a change from precarious to permanent employment (OR 2.57, 95% CI 1.20–5.52) only in females, using the KOWEPS data from 2007–2008 (2). This association with a change from permanent to precarious employment among females was consistent with our study, but among males our findings were different. In our study, a change in employment status from full-time permanent to non-permanent employment among both sexes was associated with the development of new-onset severe depressive symptoms, while a change from non-permanent to full-time permanent employment did not show a statistically significant association. Though statistically not significant, a change in employment status from non-permanent to a full-time permanent position among female heads of household was negatively associated with severe depressive symptoms, but female non-heads of household showed a positive association. Possible reasons for the present study’s different findings may be consideration of head-of-household responsibility, different categories of employment change status, adjustment for baseline CES-D-11 score, the exclusion of older people, or a longer follow-up period of our study.

Because previous studies did not stratify according to head-of-household status, the effect of being head of household was not considered. Our results showed the combined effect of head-of-household responsibility and sex on the development of new-onset depressive symptoms. This combined effect may indicate whether a worker is head of household and sex are important factors in the development of severe depressive symptoms. Under the influence of strong patriarchal social traditions in Korea (25), female heads of household must undertake responsibility for both breadwinning and household chores. In addition to the difficulty in combining work with household chores, having a female head of household may indicate a family’s low socioeconomic status.

There are several limitations of this study. First, although we adjusted baseline CES-D-11 score and excluded workers with moderate depressive symptoms, we could not completely remove bias introduced by the healthy worker effect. Workers with poor mental health are less likely to have full-time permanent employment status than workers with good mental health, and there may be a tendency for them to transition from full-time permanent to precarious employment (7). Second, differentiation between full-time permanent and precarious employment in this study might not be generalizable due to the different legal and social classifications of employment status between countries. However, if limited to East Asian countries, such as South Korea and Japan, which use similar classifications, the results of our study could be comparable with other studies. Third, the cumulative effect of precarious employment could not be assessed due to lack of information in the KOWEPS. However, because employment status and change in employment status in our study were measured annually and treated as time-dependent variables, the cumulative effect might be attenuated among workers with a change in employment status. Fourth, the harmful effects of the underlying work characteristics associated with specific forms of employment were not considered in our study due to lack of information in the KOWEPS. So, the effect of certain employment status on depressive symptom could be mediated by underlying work characteristics. Fifth, we could not exclude subjects with major depressive disorder so some subjects with anti-depressive medication could be included in the baseline subjects. Sixth, we could not reject reverse causality. Due to the frequent transition of employment status and fluctuation of mood status, we used present CES-D-11 score and main employment status of last year. So, the exact onset time of depressive symptom could not be measured.

Despite the above limitations, the present study has several strengths. First, the study design was longitudinal, with a 6-year follow-up. We excluded workers with moderate depressive symptoms (CES-D-11 score ≥9) at baseline, which was lower than the cut-off for severe depressive symptoms (CES-D-11 score ≥12), and adjusted for baseline CES-D-11 score. There have only been a few longitudinal studies of this subject in East Asia (2, 3). Second, all variables, including employment status, in the present study were time-dependent and measured annually. Moreover, change in employment status was added to the analysis to explain the effect of job transition. Third, stratification by head of household status explained a possible mechanism for why the results for female workers differed from those for male workers in previous longitudinal studies in East Asia (2, 3). Whether a worker is head of the household might be a proxy variable for voluntary or involuntary basis of precarious employment. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is one of the first to report the effect of precarious employment on new-onset severe depressive symptoms according to whether participants are heads of household or not (26). Third, study subjects were economically active in the 20–59-year-old age group at baseline. Therefore the effects of precarious employment are more easily generalizable to the working-age population.

In conclusion, this prospective 6-year follow-up study found that precarious employment is associated with the development of new-onset severe depressive symptoms among heads of household of both sexes, with an especially strong association among females. In addition, the transition from full-time permanent employment to another employment status is associated with the development of new-onset severe depressive symptoms among heads of household of both sexes, with an especially strong association among females. Given the social and occupational inequities experienced by females in East Asia, future studies should focus on the economic burden of female head-of-household workers.