In Europe, 3739 workers were reported deceased due to occupational accidents in 2014 (1). The construction industry was the economic sector most affected by fatal occupational accidents, accounting for more than 20% of such fatalities. By international standards, occupational accident rates in the Scandinavian construction industry are relatively low (1). However, considerable differences in accident rates exist between Scandinavian countries. Sweden and Denmark have much in common regarding history, social and economic systems, language, culture, and laws regulating occupational safety. Yet, in the period 2003–2008, a 39% higher fatal occupational accident rate was reported in the Danish compared to the Swedish construction industry (2). A comparative study of leadership between two countries where many factors that influence safety are similar, but which differ largely in accident rates, offers unique possibilities to discern novel features of occupational safety in the construction industry.

Leadership has previously been identified as important in relation to occupational safety, across economic sectors (3–7). Griffin & Hu (8) defined safety promoting leadership as “specific leader behaviors that motivate employees to achieve safety goals” (p200). When it comes to investigating what actually constitutes such leadership, much safety research has taken its stance in the large body of research on how different leadership styles, mainly transformational and transactional leadership, affect organizational performance (3). In Bass’ full-range leadership theory (9), which Clarke (3) evaluated in the occupational safety context, transformational leadership consists of four facets: (i) intellectual stimulation, ie, managers challenge assumptions, and encourage employees to expand their problem-solving skills; (ii) individualized consideration, ie, managers show interest in employees’ personal and professional development and listen to employees’ needs and concerns; (iii) inspirational motivation, ie, managers inspire employees towards goals, provide meaning, optimism and enthusiasm, and articulate visions that are appealing and inspiring; and (iv) idealized influence, ie, managers instill confidence and behave in positive ways that support the employees’ identification with their manager. Active transactional leadership consists of two facets: (i) contingent reward, ie, managers clarify expectations and provide rewards in exchange for employees meeting such expectations; and (ii) active management-by-exception, ie, managers monitor work progress and employees’ behavior and take corrective action to prevent deviations from standards. The full-range leadership theory also includes two facets of passive/avoidant leadership: (i) passive management-by-exception, ie, managers take corrective actions once problems have occurred; and (ii) laissez-faire, ie, managers display avoidant behaviors and lack of leadership. Transformational and active transactional leadership have been found to be positively related to safety outcomes in different settings (3, 7, 10), whereas passive/avoidant leadership has been found negative for safety (7, 10). The associations between safety outcomes and the facets of transformational and active transactional leadership have also been confirmed in the construction industry (11).

Cross-cultural research on how leadership is valued and practiced in Sweden compared to Denmark describe Swedish leadership as particularly participative and consensus-seeking (12–14). The primal component of participative leadership is subordinate participation in decision-making (15), distinguishing participative leadership from transformational leadership since the latter can be either participative or directive (16). Swedish leadership has also been described as rule-oriented and occupied with formal structures and procedures (12, 13, 17). Swedish managers scored considerably higher than their Danish colleagues on the procedural leadership scale in the Global Leadership and Organizational Behaviour Effectiveness Project (GLOBE) (17). The effectiveness of rule-oriented leadership is generally disputed and rule-oriented leaders are often regarded as stagnant and inflexible (17). However, leadership aimed at enhancing safety practices may demand a certain degree of formality and rule-orientation (18, 19), particularly at construction sites, where rule-breaking has been found commonplace (20).

The aim of the present study was to assess the influence of transformational, active transactional, rule-oriented, participative, and laissez-faire leadership on safety climate, safety behavior, and accidents in Swedish and Danish construction industry. As a first step, we wished to confirm that previous research, showing a positive relation between transformational/active transactional leadership and safety outcomes, and a negative relation between laissez-faire leadership and safety, was valid in Swedish and Danish construction industry. Moreover, we also wished to investigate if rule-oriented and participative leadership promote safety outcomes in this context.

Occupational safety is commonly measured as the number of work-related accidents. However, accidents are relatively rare and therefore influenced by stochastic effects. Furthermore, accidents are a lagging indicator of safety (21). Hence, in addition to accident occurrence, safety needs to be measured also by more pervasive and proximal safety outcomes. Safety behavior and safety climate are well-established indicators of workplace safety and recognized as antecedents strongly associated with fewer accidents (22).

Hypothesis 1: Transformational, active transactional, rule-oriented and participative leadership are positively related to safety climate and safety behavior and negatively related to accidents; whereas laissez-faire leadership is negatively related to safety climate and safety behavior, and positively related to accidents.

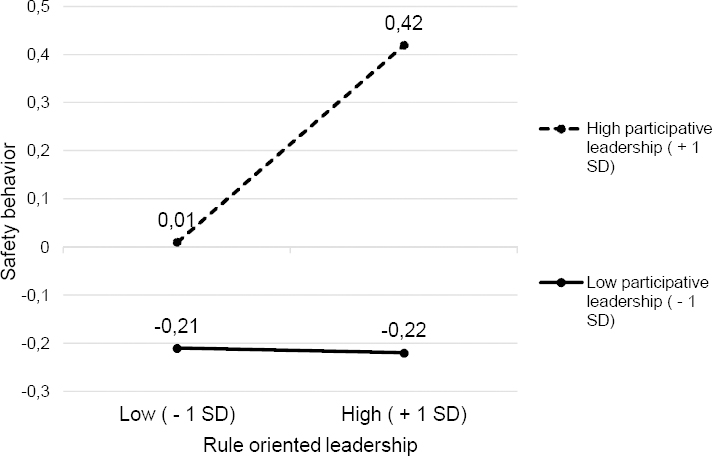

Since previous research findings on the effects of rule-oriented leadership are somewhat counter indicative (17), the role of such leadership on safety outcomes needs to be further investigated. Based on an interview study on conditions in the Swedish and the Danish construction industries, Grill and colleagues (12) presented a theoretical model suggesting a combination of participative decision-making and rule-orientation as beneficial for workers’ safety behavior at construction sites. The results indicated that Swedish construction workers, more than their Danish colleagues, participate in planning the execution of their work. Participation encouraged voice behavior, where safety critical issues were raised and solved, and participation also supported further manager–employee cooperation. The model also suggested that participation in planning may contribute to a higher legitimacy of the resulting plans and procedures and workers’ adherence to safety procedures. If managers and workers develop work plans and safety procedures in cooperation, managers would also be more bound to ensure adherence to the agreed rules and procedures. This indicates that a positive effect of rule-oriented leadership may be conditioned by participative leadership. To further illuminate the relationship between rule-oriented and participative leadership, and their combined effect on safety outcomes, we therefore formulated a second hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2: The effect of rule-oriented leadership on workers’ safety behavior is moderated by the level of participative leadership.

The effectiveness of leadership behaviors has been found to be dependent on the specific context in which they are applied (23–25). It is feasible that leadership behaviors that are effective to promote safety at Swedish construction sites may not be so at Danish sites. Better knowledge on the impact of different aspects of leadership on occupational safety in different contexts could further develop safety leadership theory, but also help to reduce high accident rates. We therefore formulated a third set of hypotheses.

Hypothesis 3a: The influence of leadership behaviors on safety outcomes is similar in the Swedish and Danish construction industries.

Hypothesis 3b: The types of leadership behaviors related to positive safety outcomes (as identified in hypothesis 1) are more common in the Swedish than Danish construction industry.

Method

Participants and procedure

This paper presents a questionnaire study conducted among construction workers at construction sites in Sweden and Denmark between 1 January and 1 July 2016. The sampling frame consisted of all sites that had been registered by the National Work Environment Authorities in Sweden and Denmark (26) between 1 October and 15 November 2015 and that were in operation anytime between 1 January and 1 July 2016. Of the 160 construction sites randomly selected, contacted, and invited to participate in the study, 117 sites accepted the invitation and 1270 paper questionnaires were administered. In Sweden, the questionnaires were administered by the site managers, and in Denmark the questionnaires were administered by members of the research team. In total, 811 construction workers at 85 sites responded to the questionnaire, giving a site response rate of 73% and an individual response rate of 64%. The characteristics of the participants are described in table 1.

Table 1

Characteristics of the participants. [SD=standard deviation].

Measures

The respondents were initially asked to identify their current first line formal leader and to relate all subsequent ratings to this person. The respondents rated how often this leader engaged in the behaviors described in each item, using a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (always). Transformational/transactional leadership was measured with 18 items from the Multi-Factor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) (27). Two items were included for each of three facets of transformational leadership: intellectual stimulation (sample item: “Seeks differing perspectives when solving problems”); individualized consideration (sample item: “Helps others to develop their strengths”); and inspirational motivation (sample item: “Talks enthusiastically about what needs to be accomplished”). Idealized influence was not measured due to its conceptual overlap with inspirational motivation (28, 29). Four items were included for each of the two facets of active transactional leadership: contingent reward (sample item: “Expresses satisfaction when others meet expectations”); and active management-by-exception (sample item: “Focuses attention on irregularities, mistakes, exceptions, and deviations from standards”). Finally, four items were included for laissez-faire leadership (sample item: “Avoids getting involved when important issues arise”). Passive management-by-exception was not measured due to its conceptual overlap with laissez-faire leadership (10, 30). Rule-oriented leadership was measured with two items from the procedural/bureaucratic scale of the GLOBE questionnaire (31) (sample item: “Enforces rules and regulations”). Participative leadership was measured with three items from the participative decision-making scale of the Empowering Leadership Questionnaire (ELQ) (15) (sample item: “Uses my work group’s suggestions to make decisions that affect us”).

This 8-factor conceptual model was tested with confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in AMOS version 24.0 and found to represent the data well (χ2 (224) = 834.0; CFI = 0.94; RMSEA = 0.058) (32). When comparing the 8- to a 5-factor model, in which the facets of transformational and active transactional leadership were collapsed into their higher-order constructs (χ2 (242) = 1648.3; CFI = 0.86; RMSEA = 0.085), the 8-factor model was found to represent data better than the 5-factor model (Δχ2 = 814.3; P<0.001). Correlations between participative leadership and the transformational leadership facets ranged between 0.46–0.58, confirming that participative leadership is distinct from transformational leadership.

The safety outcome measures were perceived safety climate, self-rated safety behavior, and self-rated accident experience. Safety climate was operationalized as individuals’ perceptions of a shared safety climate (22) using a referent shift strategy (33). It was measured with eight items from the Nordic Safety Climate Questionnaire (NOSACQ-50) (34), comprising workers’ perceptions of superiors’, as well as co-workers’, safety priorities and behaviors combined into an overall safety climate measure (35) (sample item: “We who work here try to find a solution if someone points out a safety problem”). Participants rated to what extent they agreed with the statements using a 6-point scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Workers’ participative and compliance safety behaviors were measured with five items from Neal & Griffin (36), combined into an overall safety behavior measure (sample item: “I ensure highest level of safety when I carry out my job”). Participants rated how often they engaged in each type of behavior, using a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (always). Accident experience was measured with a single item: “How many times, during the last three months, have you had an accident at work that forced you to stop working for at least one hour?”. The responses were binary coded as 0 (no accident) and 1 (≥1 accidents). Descriptive statistics, inter-correlations, and internal consistency data are presented in table 2. Descriptive statistics for each sub-sample is available as supplementary material (www.sjweh.fi/index.php?page=data-repository).

Table 2

Descriptive statistics and inter-correlations for all variables. [SD=standard deviation; α=Cronbach’s alpha].

Statistical analysis

The nested structure of the data at construction sites was accounted for by conducting mixed-model regression analyses, with random intercepts, in SPSS version 24 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Maximum likelihood (ML) was used to estimate all regression models. All variables were standardized [mean 0, standard deviation (SD) 1], implying that all parameter estimates reported in the result section are expressed in SD. All regression coefficients were estimated under control of age, gender, profession and company size.

Regression coefficients for the effects of leadership behaviors, on safety climate and safety behavior were estimated with univariate mixed model regression analyses, separately for each predictor variable. Odds ratios(OR) for the effects of leadership behaviors on accidents were estimated with binary logistic regression analyses, again separately for each predictor variable.

To assess the extent to which the effect of rule-oriented leadership on workers’ safety behavior was moderated by participative leadership, a regression model including only the control variables was compared with (i) a regression model that included the control variables and the main effects of rule-oriented and participative leadership and (ii) a regression model including the control variables, the main effects, and the interaction effect between rule-oriented and participative leadership. χ2-tests were conducted to assess the differences in log likelihoods between the regression models. This procedure was conducted both in the complete sample and separately in each sub-sample.

To assess differences in the effects of leadership behaviors on safety outcomes at Swedish compared to Danish construction sites, univariate regression coefficients for leadership behaviors on safety outcomes were first estimated separately in each sub-sample. Thereafter, in the complete sample, interaction effects between leadership behaviors and national context were estimated for all safety outcomes.

Finally, to assess the differences in the levels of leadership behaviors at the Swedish and Danish construction sites, regression coefficients for the effect of national context were estimated for each leadership behavior.

Results

Hypothesis 1: associations between leadership and safety

All three aspects of transformational leadership, as well as both aspects of active transactional leadership, were positively associated with safety climate and safety behavior. No associations were found between either transformational or active transactional leadership and accidents.

Laissez-faire leadership was found to be negatively associated with safety climate but showed no associations with either safety behavior or accidents.

Rule-oriented leadership was positively related to safety climate and safety behavior. Furthermore, rule-oriented leadership was negatively associated with accidents.

Participative leadership was positively associated with safety climate and safety behavior but unrelated to accidents.

Thus, all significant associations between safety outcomes and transformational, active transactional, rule-oriented, participative, and laissez-faire leadership, were found to be in the hypothesized direction. However, rule-oriented leadership was the only leadership behavior found to be negatively associated with accidents. Hence, hypothesis 1 was partly supported.

Univariate regression coefficients for the associations between leadership behaviors and safety climate, safety behavior, and OR for accidents are displayed in table 3.

Table 3

Univariate regression coefficients (β) and odds ratios (OR), estimated under control of age, gender, profession and company size for the effects of leadership behaviors on safety climate, safety behavior and accidents (N=811). [SE=standard error; 95% CI=95% confidence interval.]

| Safety climate | Safety behavior | Accidents | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| β | SE | β | SE | OR | 95% CI | |

| Intellectual stimulation | 0.21 a | 0.04 | 0.26 a | 0.04 | 1.05 | 0.82–1.34 |

| Individualized consideration | 0.26 a | 0.04 | 0.29 a | 0.04 | 1.18 | 0.92–1.51 |

| Inspirational motivation | 0.23 a | 0.04 | 0.22 a | 0.04 | 1.23 | 0.96–1.58 |

| Contingent reward | 0.32 a | 0.04 | 0.28 a | 0.04 | 1.04 | 0.81–1.33 |

| Active management- by-exception | 0.09 b | 0.04 | 0.16 a | 0.04 | 1.18 | 0.92–1.50 |

| Laissez-faire | -0.40 a | 0.04 | -0.07 | 0.04 | 1.05 | 0.83–1.33 |

| Rule-oriented | 0.40 a | 0.03 | 0.15 a | 0.04 | 0.78 b | 0.62–0.98 |

| Participative | 0.28 a | 0.04 | 0.24 a | 0.04 | 1.05 | 0.82–1.35 |

Hypothesis 2: moderating effect of participative leadership

The relation between rule-oriented leadership and workers’ safety behavior was moderated by the level of participative leadership. This moderating effect was tested and found valid in both the Swedish and Danish sub-samples. Hence, hypothesis 2 was supported. The regression coefficients for the complete sample are shown in table 4. The relationship between rule-oriented leadership and safety behavior, under condition of low (-1 SD) respectively high (+1 SD) participative leadership is presented in figure 1.

Table 4

Regression coefficients (β) for the combined effects of participative and rule oriented leadership on safety behavior, estimated under control of age, gender, profession and company size, (N=811). Intraclass correlation (ICC)=0.058. [AIC=Akaike information criterion; InL=log likelihood; SE=standard error.]

| Model 1 a | Model 2 b | Model 3 c | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

| β | SE | InL | AIC | β | SE | InL | Diff InL | AIC | R2 % d | β | SE | InL | Diff Inl | AIC | R2 % d | |

| Fixed effects | ||||||||||||||||

| Rule-oriented | 0.100 e | 0.038 | 0.101 e | 0.038 | ||||||||||||

| Participative | 0.213 e | 0.039 | 0.215 e | 0.039 | ||||||||||||

| Rule-oriented × participative | 0.104 e | 0.030 | ||||||||||||||

| Random effects | ||||||||||||||||

| Residuals | 0.899 | 0.055 | 0.845 | 0.048 | 0.829 | 0.047 | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 0.010 | 0.025 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||||||||

| Fit indices | 1719.2 | 1749.2 | 1673.8 | 45.4 e | 1708.8 | 7.0 | 1662.1 | 11.7 e | 1698.1 | 8.8 | ||||||

Hypothesis 3a: moderating effects of national context

In the two countries, 22 of the 24 assessed associations between leadership behaviors and safety outcomes were similar. National context moderated only two associations, both related to safety climate. Firstly, the positive effect of active management-by-exception on safety climate was found only at the Danish construction sites (β=0.22, P=0.003). Secondly, the positive effect of participative leadership on safety climate was more pronounced at the Swedish than Danish construction sites (β=0.19, P=0.011). Hypothesis 3a was thus generally supported. The univariate regression coefficients for the effects of leadership behaviors on safety climate, safety behavior, and OR for accidents at the Swedish and the Danish sites, respectively, are displayed in table 5.

Table 5

Univariate regression coefficients (β) / odds ratios (OR) for the effects of leadership behaviors on safety climate, safety behavior and accidents at Swedish and Danish construction sites, estimated under control of age, gender, profession and company size. [SE=standard error; 95% CI=95% confidence interval; SWE=Swedish; DAN=Danish]

| Safety climate | Safety behavior | Accidents | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| SWE (N=346) | DAN (N=465) | SWE (N=346) | DAN (N=465) | SWE (N=346) | DAN (N=465) | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Intellectual stimulation | 0.23 a | 0.06 | 0.21 a | 0.04 | 0.27 a | 0.06 | 0.25 a | 0.05 | 0.76 | 0.51–1.13 | 1.25 | 0.90–1.75 |

| Individualized consideration | 0.25 a | 0.06 | 0.28 a | 0.04 | 0.26 a | 0.05 | 0.31 a | 0.05 | 1.27 | 0.85–1.92 | 1.14 | 0.82–1.58 |

| Inspirational motivation | 0.21 a | 0.05 | 0.29 a | 0.04 | 0.25 a | 0.05 | 0.23 a | 0.05 | 1.17 | 0.80–1.71 | 1.28 | 0.90–1.84 |

| Contingent reward | 0.36 a | 0.06 | 0.30 a | 0.04 | 0.26 a | 0.06 | 0.27 a | 0.05 | 0.88 | 0.59–1.32 | 1.11 | 0.79–1.55 |

| Active management-by-exception | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.21 a | 0.05 | 0.14 a | 0.05 | 0.18 a | 0.06 | 0.95 | 0.67–1.35 | 1.34 | 0.93–1.93 |

| Laissez-faire | -0.40 a | 0.05 | -0.36 a | 0.05 | -0.06 | 0.06 | -0.08 | 0.05 | 1.11 | 0.78–1.57 | 0.93 | 0.66–1.31 |

| Rule-oriented | 0.44 a | 0.05 | 0.33 a | 0.05 | 0.15 a | 0.06 | 0.11 b | 0.05 | 0.67 b | 0.47–0.96 | 0.91 | 0.65–1.26 |

| Participative | 0.38 a | 0.06 | 0.19 a | 0.05 | 0.28 a | 0.06 | 0.20 a | 0.05 | 0.87 | 0.57–1.32 | 1.19 | 0.85–1.66 |

Hypothesis 3b: Levels of leadership behaviors at Swedish and Danish construction sites

Rule-oriented leadership and participative leadership were both found to be more common at the Swedish than Danish construction sites. Active management-by-exception was more common at the Danish sites. Univariate regression coefficients for the effects of national context on leadership behaviors are displayed in table 6.

Table 6

Univariate regression coefficients and standard errors (SE) for the effect of national context on leadership behaviors, estimated under control of age, gender, profession and company size. β represents the Swedish levels (N=346) in relation to the Danish (N=465).

| Effect of national context | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| β | SE | |

| Intellectual stimulation | 0.07 | 0.09 |

| Individualized consideration | 0.16 | 0.10 |

| Inspirational motivation | -0.11 | 0.11 |

| Contingent reward | 0.11 | 0.11 |

| Active management-by-exception | -0.28 a | 0.11 |

| Laissez-faire | -0.09 | 0.11 |

| Rule-oriented | 0.32 b | 0.10 |

| Participative | 0.34 b | 0.10 |

Only two out of the seven leadership behaviors related to positive safety outcomes were found to be more extensively practiced at the Swedish than the Danish construction sites. Hence, hypothesis 3b was partially supported.

Discussion

The study supported previous research stating leadership as important for occupational safety. The overall interpretation of the results is that the generally endorsed transformational and active transactional leadership styles supported safety also in the construction industries of Sweden and Denmark. Laissez-faire leadership was negatively related to safety.

House and colleagues (17) identified rule-oriented leadership as generally an ineffective style of leadership, associated with self-centered, status-conscious, conflict-inducing, and face-saving management. In our results, however, rule-oriented leadership was found to be positively related to occupational safety. The results also showed that the relation between rule-oriented leadership and workers’ safety behavior was moderated by participative leadership. This indicates that in order to have a positive effect of rule-orientation also on workers’ safety behavior, site managers need to invite construction workers to participate in planning and decision-making. By enforcing rules, procedures, and plans that have been formulated through collective efforts, involving participative decision-making and consensus-seeking processes, managers acknowledge the workers’ contributions. Participating in the formulation of rules, procedures and plans stimulates commitment to follow the resulting decisions.

Although largely similar, the effects of leadership behaviors on safety outcomes were not entirely consistent across national contexts. While the effects on safety outcomes of transformational, contingent reward, rule-oriented and laissez-faire leadership were similar in both countries, the positive effect of participative leadership was not as pronounced at the Danish as at the Swedish construction sites. This is in accordance with previous research that found transformational and contingent reward leadership to be effective across cultures, while the effect on organizational outcomes of participative leadership was found to be culture-specific (37, 38). It should however be kept in mind that the difference in influence in the present study was only a matter of degree. Participative and active management-by-exception leadership was associated with positive safety outcomes both at the Swedish and at the Danish construction sites.

The difference in accident rates between the Swedish and Danish construction industry may, at least to some extent, be explained by differences in leadership practices, since the results indicated that Swedish construction site managers apply more rule-oriented as well as more participative leadership than their Danish colleagues. The Danish managers, on the other hand, apply more active management-by-exception leadership.

Limitations

Employing cross-sectional data to assess causal relations is a suboptimal method. However, the effects of transformational and active transactional leadership on safety outcomes have previously been established in longitudinal research (4, 7). The present study contributes by adding rule-oriented and participative leadership and comparing the effects of these leadership behaviors on safety outcomes with the recognized effects of transformational and active transactional leadership. In addition, different leadership behaviors had differential influence on the outcomes, which speaks against the results being severely inflated by common method bias.

The interaction effect between rule-oriented leadership and participative leadership on workers’ safety behavior was interpreted as indicating that participative leadership moderates the effect of rule-oriented leadership. Due to the cross-sectional design, another interpretation is empirically equally valid: rule-oriented leadership moderates the effect of participative leadership, ie, that participative leadership at construction sites is more effective if it is used to develop rules collectively. However, the theoretical model outlined by Grill and colleagues (12) describes how workers’ participation in the construction of rules, procedures, and plans may contribute to a higher legitimacy for the resulting decisions and contribute to an increased adherence to safety rules and procedures. This theoretical underpinning supports the interpretation that the positive effect of rule-oriented leadership is conditioned by participative leadership, rather than the other way around. Nevertheless, the interaction effect between rule-oriented and participative leadership on workers’ safety behavior, which, to our knowledge, has not been identified previously, deserves to be further studied with longitudinal research designs.

The full-range leadership theory has been criticized for inconclusive empirical support for its component structure (39, 40). In the present study, six out of eight components were included; the two components not measured were idealized influence and passive management-by-exception. Consequently, the full-range leadership theory was not exhaustively covered. However, the conceptual and empirical overlap has been found to be substantial between idealized influence and inspirational motivation (28, 29), as well as between passive management-by-exception and laissez-faire leadership (10, 30). Therefore, it is unlikely that the effects on safety outcomes of idealized influence and passive management-by-exception diverge substantially from the effects, identified in the present study, on safety outcomes of inspirational motivation and laissez-faire leadership, respectively.

The associations between leadership behaviors and occupational accidents should be interpreted with caution. Occupational accidents are relatively rare, and stochastic effects may distort the results. However, accident experience was reported among 13% of the respondents, a rather high frequency, which constrains the influence of stochastic effects. Also, the accident experience measure should be interpreted together with the other two safety outcomes, safety behavior and safety climate, identified in previous research as leading indicators of occupational safety (21, 22). Specifically for rule-oriented leadership, the results regarding all three outcome variables were consistent.

The effects of leadership on safety outcomes were assessed merely on the individual level, which may be a limitation, since effects are commonly also present on an organizational level (41). However, as described by Christian and colleagues (22), assessing the impact of organizational factors on safety outcome on an individual level, neglecting the aggregated effects operating on the group and organizational levels, implies an underestimation of the actual influence. Hence, the results of the present study regarding the influence of leadership on safety outcomes may be conservative rather than inflated.

The response frequency was higher in Denmark than Sweden. The results indicating rule-oriented and participative leadership to be more common among Swedish construction site managers than Danish, should therefore be interpreted with some caution. It is possible that the respondents were more positive about the safety leadership than the non-responders. However, the telephone reminders (three) to managers of non-responding Swedish sites indicated that the questionnaires had not been distributed due to time limitations. Although it is not evident that such managers would be less rule- or participative-oriented, and the results are consistent with previous findings (12, 42), these differences deserve additional study in future research.

Concluding remarks

The results indicated that the effects of leadership behaviors on safety outcomes are largely similar in the Swedish and Danish construction industries. The differences in occupational accident rates in the two countries’ construction industries may thus partially be explained by differences in the degree to which these leadership behaviors are practiced. Particularly rule-oriented and participative leadership behaviors were both more practiced at the Swedish than Danish construction sites.

The results suggest that applying less laissez-faire leadership and more transformational, active transactional, participative, and rule-oriented leadership, would be effective for construction site managers to improve occupational safety in the construction industry. Rule-oriented leadership was, however, positively associated with workers’ safety behavior only in conjunction with participative leadership. To increase safety behavior among construction workers, the establishment and enforcement of rules by construction site managers should rest on the collaborative involvement of the construction workers in the decision-making process. Through rule-oriented and participative leadership, construction workers’ professional competence regarding how construction work can be performed in a safe and efficient manner may be put to use. Workers’ motivation to comply with safety regulations and participate in proactive safety activities may thus be promoted.