Over the last 30 years, there have been substantial changes in the global labor market. In the Western countries, factors such as globalization, neoliberal politics, technological advances and deindustrialization have contributed to push the development of a more flexible workforce forward. Combined with financial crises and rising unemployment rates, the prevalence of non-standard employment forms has been on the rise. It has been estimated that nearly a third of the European workers have a precarious employment situation today (1).

The term “precarious employment” (PE) is used to describe a multidimensional set of unfavourable work/employment characteristics that may be experienced in various degrees by workers; the common denominator being lack of security in some domain. The term comprises both short-term and temporary contracts, as well as powerlessness, vulnerability, employment insecurity and insufficient wages. There is no internationally accepted definition of precarious employment, but several multidimensional constructs have been proposed, including those described by Guy Standing (2) and the Employment Precariousness Scale (3). According to the International Labor Organization (ILO), a precarious job is defined by “uncertainty as to the duration of employment, multiple possible employers or a disguised or ambiguous employment relationship, a lack of access to social protection and benefits usually associated with employment, low pay, and substantial legal and practical obstacles to joining a trade union and bargaining collectively” (1). A detailed description of what defines a precarious employment according to these three sources can be found in Appendix I, and a side-by-side comparison in Table 1 below.

Table 1

Side-by-side comparison of three different definitions of Precarious Employment in relation to search string returns

Several studies and reviews have found an association between precarious employment and adverse health outcomes, decreased job satisfaction and suboptimal psychosocial work environment (4-6). Temporary employees tend to have less education about the work place, more stressful/heavier work load, and a greater tendency to work when sick (5). Temporary employees are also likely to be repetitively new at their workplace (i.e., to have a short job tenure) which is a known risk factor for occupational injuries (7). Several reviews have been published regarding different dimensions of precarious employment and mainly self-reported health outcomes (5, 6, 8, 9). However, a systematic review of precarious employment and its association to a well-defined and objective outcome such as occupational injuries is highly relevant and lacking.

The objective of this review was to collect and summarize existing scientific research on the relation between different dimensions of precarious employment and occupational injuries.

Methods

Review protocol and eligibility criteria

A protocol was developed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocol (PRISMA-P) checklist for systematic literature reviews (10). It can be read in full in appendix I (www.sjweh.fi/show_abstract.php?abstract_id=3720). The inclusion criteria for this review were as follows: (i) observational studies; (ii) adult working population (18-65 years), ≥300 participants; (iii) exposed to precarious employment (defined as single or multiple exposures to employment characteristics as outlined in the introduction and table 1); (iv) controls not exposed to the studied dimension of precarious employment in a comparable population; (v) outcomes included incidence or prevalence of occupational injuries, with statistics on results in odds ratio (OR), rate/risk ratio (RR), hazard ratio (HR) or incidence risk ratio (IRR); (vi) setting included European Economic Area (Member States of the European Union, Iceland, Lichtenstein and Norway), Switzerland, Australia, New Zealand, USA and Canada; (vii) Swedish or English language; (viii) published or “ahead of print” original research articles from peer-reviewed journals published 1 January 1990 to 2 September 2017.

Information sources and search strategy

Literature searches were performed on 9 February 2017 and 1 June 2017. Three electronic databases were used as sources: PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science.

Keywords and strings were suggested based on multidimensional constructs and experience from reading related literature. In order to develop a comprehensive search string, key dimensions from all constructs outlined in table 1 were included. The search strategy was discussed within the team and externally reviewed before finalizing the protocol. The final search terms are presented in table 2, and database-specific search strings for all three databases can be found in appendix III (www.sjweh.fi/show_abstract.php?abstract_id=3720).

Table 2

The identified key words included in the search strings

When the systematic search strategy, screening and assessments were fully executed, a final search for review articles was performed with the purpose to manually search for articles in reference listings. The same databases were used to search for reviews.

Study selection process

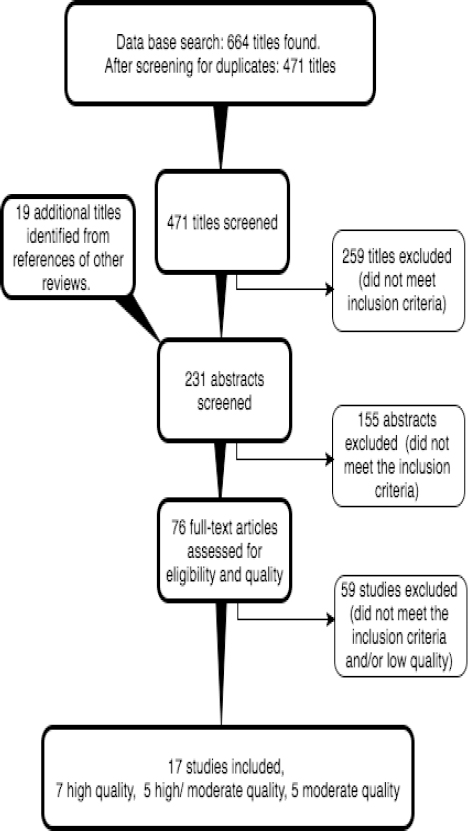

We used EndNote X8 to manage reference libraries. During each step in the selection process libraries were exported and saved as duplicates in order to allow back-tracking through the whole process. Of the four reviewers (two PhD, one PhD student and one graduate student), at least two individually evaluated each reference by title, abstract, and fulltext article. References clearly not meeting inclusion criteria were excluded at each stage, with remaining ones proceeding to the next level of assessment (figure 1). Each step of the review process included an initial piloting of a limited number of papers where concordance in judgments of relevance and quality between reviewers was calibrated. Differences between the reviewers’ assessments at any stage of the selection process were discussed until a consensus decision was achieved.

The quality assessment of articles in fulltext was performed using an online scoring sheet constructed as an adaptation of the evaluation form used by the Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services for systematic reviews (11) which is appended in appendix IV (www.sjweh.fi/show_abstract.php?abstract_id=3720). Eight dimensions of quality were assessed: (i) selection bias (how the sample was collected and assembled and how representative it was for the target population); (ii) bias in exposure (whether the circumstances except for occupational exposure were similar for the participants and if potential confounders were adequately handled); (iii) bias in outcome measures (if the outcome was measured with well-defined and/or validated methods at an appropriate point in time, by self-report or objective measures; if the statistical analysis took correction of imbalances in baseline variables between groups with different exposures in an adequate manner); (iv) bias in loss to follow-up (handling and description of dropouts); (v) bias in reporting results; (vi) conflict of interests; (vii) transferability; and (viii) study design and statistical methodology (if the study design was adequate for the investigated research question and if the number of participants were adequate to obtain statistical power). Each of the five dimensions of bias were assessed through a subset of questions and based on these answers received a dimension-specific risk of bias (low, moderate or high). Based on the above described quality assessment, the reviewer assigned each article a global assessment indicating “high quality”, “high/moderate quality”, “moderate quality”, “low/moderate quality” or “low quality”. Only articles graded as moderate quality or higher were included in the review. Discrepancies in quality assessment among the reviewers resulted in a referral to a whole-day consensus meeting where IK, LS and TB participated with a focus on those articles of borderline low/moderate quality.

Synthesis of results and statistical methods

The results are presented as a systematic narrative synthesis. Because of the variation in exposures as well as outcome definitions, no meta-analysis was performed. When no confidence intervals (CI) were presented in the original study, we derived 95% CI from P-values using the method proposed by Altman et al (12). Guidelines for meta-analyses and systematic reviews of observational studies (MOOSE) (13) were followed when preparing this manuscript.

Results

Study selection

Figure 1 illustrates an overview of the selection process. The database searches resulted in 664 titles. After screening for duplicates, 471 titles remained. Of these, 259 were dismissed as not relevant by title screening, leaving 212 abstracts to be assessed. Additionally, 19 abstracts were added through manual search in reference lists of related reviews. These included, the screening of 231 abstracts resulted in 155 exclusions (not matching inclusion criteria) and 76 articles to be read in fulltext. Abstracts were missing for 4 articles, and they were hence included in the fulltext assessment, leaving a total of 80 fulltexts to be evaluated. Of these, 59 studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria and/or were assessed to be of low quality were excluded. This left 17 studies for inclusion in the final review, of which 7 were judged to be of high quality, 5 of high/moderate quality and 5 of moderate quality. A table summarizing the assessed risk of bias and the form used for assessment can be found in Appendix III (www.sjweh.fi/show_abstract.php?abstract_id=3720).

Study characteristics

The characteristics of individual studies included in this review are summarized in table 3. Included studies were published in 1997–2017, but the underlying data was collected from 1988–2014 with a predomination of the late 1990s and early 2000s. Most study groups were general samples of the working population. Four of the studies used a population of blue-collar workers (14–17) and two of the studies used populations based on health care workers (18, 19). The exposure measurements came either from corporate administrations (eg, payrolls), national statistics registers, or were self-reported. Eight studies used self-reported data on occupational injuries, and seven had extracted their data from various types of registers whereof four used data registered by the employers. Three studies used data that was clinically confirmed by a physician.

Table 3

Characteristics of included articles. [CI=confidence interval; IRR=incidence rate ratio; OR=odds ratio; RR=rate ratio/risk ratio.]

| Author, year | Country, setting | Total (men/women) | Exposure | Study design | IRR / OR / RR (95% CI / P-value) | Quality assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aiken et al, 1997 (24) | USA, nurses working in hospitals with AIDS care | 910 (NA) | Temporary employment | Cohort | Temporary employment 1.65 (0.63-3.67) | Moderate |

| Alali et al, 2016 (25) | Belgium, convinience sample, 2009, 2011 | 1 886 (1055/ 831) |

Temporary contract Part-time Job insecurity |

Cross-sectional |

Temporary vs. permanent: 0.58 (0.28–1.20) Full-time vs. half-time: 0.99 (0.51–1.94) Job insecurity, yes vs. no: 1.55 (0.99–2.41) |

High/ Moderate |

| Alali et al, 2017 (20) | Belgium, employed workers (not self-employed or apprentices), 2010 | 3 343 (1769/ 1574) |

Temporary contract Multiple jobs |

Cross-sectional |

Temporary contract 1.163 (0.739–1.831) Multiple jobs 1.361 (0.827–2.240) |

High |

| Alamgir et al, 2008 (18) | Canada, employed registered nurses and care aides, 2005–2006 | 11 607 (646/ 10 955) |

Part-time Casual work |

Cross-sectional |

Registered nurses Part-time, all injuries: 0.7 (0.6-0.9) Casual, all injuries: 0.7 (0.5–1.0) Care aides Part-time, all injuries: 0.8 (0.6–1.2) Casual, all injuries: 0.6 (0.5–0.8) |

High/ Moderate |

| Bena et al, 2011 (14) | Italy, workers on high-speed train construction site 2003–2005 | 8955 (NA) | Working for a subcontractor Length of employment contract | Cross-sectional |

Contract vs subcontractor 1.19 (0.99–1.43) Length of employment contract: 6 months 2.12 (1.72–2.60) 1 year 1.70 (1.42–2.04) 1.5 years 1.51 (1.27–1.79) 1.5–2 years 1.16 (0.98–1.37) >2 years 1 (ref) |

High/ Moderate |

| Benavides et al, 2006 (26) | Spain, all registered labor force 2000-2001 |

24 962 833 (15 388 153 / 9 574 680) |

Temporary employment | Cross-sectional |

Non-fatal: 1.04 (0.97–1.12) Fatal: 1.07 (0.91–1.26) |

High |

| Berdahl et al, 2008 (27) |

USA, workers, National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY79) 1988–2000 |

6634 (50%) | Various | Cohort | Log hourly wages: 0.955 (0.258) Union membership: 1.362 (0 .000) Insurance benefits: 1.499 (0.000) Fixed work schedule: 0.898 (0.099) Organizational tenure: 1.000 (0.190) Self-employed: 0.818 (0.064) | High/ Moderate |

| Dong, 2015 (15) |

USA, construction workers, National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY79) 1988–2000 |

1625 (50%) | Multiple jobs | Cohort |

>5 jobs 2.00 (1.39–2,88) 3-4 jobs 1.25 (1.13–1.39) 1–2 jobs 1.00 |

High/ Moderate |

| Dong et al, 2005 (16) |

USA, workers in production, National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY79) 1992–1998 |

4103 (50%) |

Multiple jobs Self-employment |

Cohort |

>1 job, 1.03 (1.02–1.04) Self-employment 1.03 (1.02–1.04) |

High |

| Engkvist et al, 2001 (19) |

Sweden, employed nursing personnel, 1992–1994 |

673 (0/673) | Part-time | Prospective case-referent |

Five clusters with different composition of fulltime/part-time Fulltime clusters: Full time: 96%: 2.1 (1.5 – 2.9) Full time: 99% : 2.2 (1.5 – 3.2) Part-time clusters: Full time: 0%: 0.5 (0.3 – 0.8) Full time: 1%: 0.4 (0.3 – 0.7) Full time: 0%: 0.7 (0.4 – 1.2) |

Moderate |

| Giraudo et al, 2016 (34) | Italy, workers (governmental and agricultural excluded), 1994 – 2005 National Insurance Institute for Occupational Injuries (INAIL) |

56 760 (35 598/ 24 162) |

Precarious careers a with work intensity high – mid - low | Cross-sectional |

High work intensity: All injuries 1.41 (1.34-1.48) Mid work intensity: All injuries 1.57 (1.45-1.70) Low work intensity: All injuries 1.24 (1.12-1.38) |

Moderate |

| Hintikka, 2011 (22) | Finland, all industries, 2006 – 2007 Labor force survey |

234 537 injuries (168 253/ 66 284) |

Work at temporary agencies | Cross-sectional |

Total: 2.26 (2.19–2.32) Men: 2.92 (2.83–3.02) Women: 1.51 (1.43–1.60) |

Moderate |

| Kubo et al, 2013 (17) | USA, hourly production workers of an aluminium company, 1996–2007 |

81 301 (63 233/ 18 006) |

Unionized plant | Retrospective cohort |

Complete case analysis 1.15 (1.04–1.27) multiple imputation 1.30 (1.23–1.37) |

High |

| Author, year | Country, setting |

Total (men/women) |

Exposure | Study design |

IRR / OR / RR (95% CI / P-value) |

Quality assessment |

| Marucci-Wellman et al, 2014 (21) | USA, workers, US National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), 1997–2011 | 268 615 (143 709 / 124 906) | Multiple jobs | Cross-sectional |

Multiple job holders vs single job holders Total 1.19 (P<0.05) Male 1.11 (P>0.05) Female 1.3 (P<0.05) |

High |

| Smith, et al, 2010 (23) |

USA, Washington State, Data from State Fund workers’ compensation claims ´2003–2006 |

342 540 claims (180 042 / 74 654) | Employed by temporary agencies | Cross-sectional | Pooled estimate for all industries 1.17 (1.14–1.19) | Moderate |

| Tucker et al, 2016 (28) |

Sweden, working adults, Swedish Longitudinal Occupational Survey of Health (SLOSH), 2010–2014 |

41 781 (50%) |

Work-time control (WTC) |

Cohort |

Injuries at work WTC 2010 0.81 (0.70–0.94) WTC 2012 0.82 (0.70–0.96) |

High |

| Wirtz et al, 2012 (29) | USA, workers, US National HealthInterview Survey(NHIS), 2004–2010 |

96 915 (48 816/ 48 099) |

Hourly pay | Cross-sectional |

Men 1.67 (1.26–2.21) Women 1.70 (1.21–2.40) Total 1.69 (1.37–2.08) |

High |

Ten studies were cross-sectional. The rest were either case–control or cohort studies. Three studies used the US National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, 1979 cohort, (NLSY79) and one study used the Swedish Longitudinal Occupational Survey of Health (SLOSH) cohort. In the former case, the three studies focused on different exposures/outcomes, hence all three were included despite using the same base population.

Dimensions of precarious employment studied and their association with occupational injuries

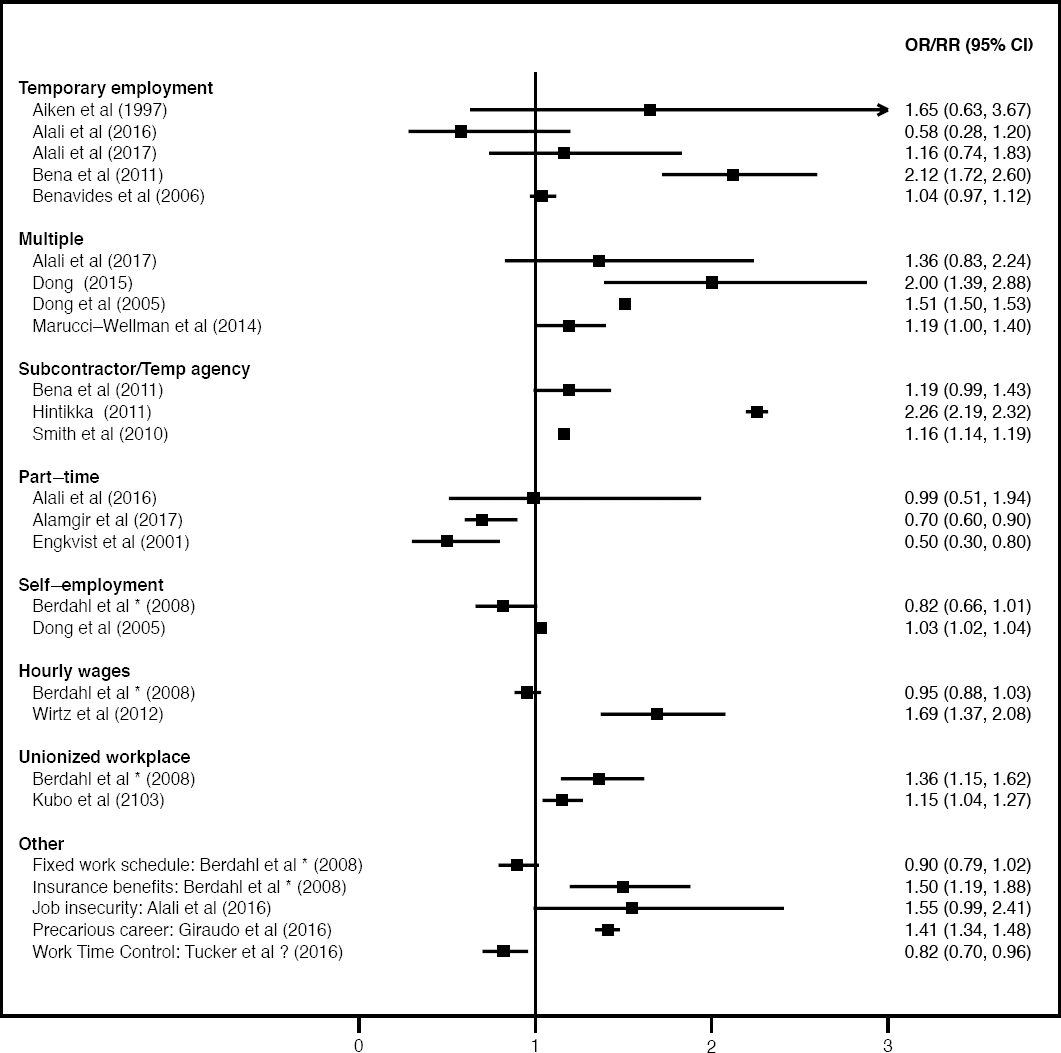

The exposures studied were (in order of most to least common) temporary employment, multiple jobs, working for a subcontractor at the same worksite/temp agency, part-time, self-employment, hourly pay, union membership, insurance benefits, flexible versus fixed work schedule, wages, job insecurity, work-time control, and precarious career trajectories. A majority of the studies reported a positive association between precarious employment and occupational injuries. All of the four studies on multiple job holders indicated that the risk for occupational injuries was higher among these individuals compared to those with only one job (15, 16, 20, 21). Being employed through a subcontractor at the same worksite or staffing agency was also associated with a higher risk of occupational injuries compared to being directly employed by the employer (14, 22, 23). Five studies investigated the relation between temporary contracts and risk of injuries. One of these found a statistically significant positive association (14), while four studies showed inconclusive results or negative associations (20, 24-26). Four studies on part-time or casual work suggested negative or no relation to occupational injuries (18, 19, 25). Only one study examined differences in distribution between fatal and non-fatal injuries, and no difference was found between temporary and permanent workers (26). Two studies of aluminum plant workers found that unionization was associated with a higher risk of occupational injuries (17, 27).

Figure 2 shows a summarization of the results and effect sizes of the 17 included studies, sorted by exposures researched. Table 3 describes each individual study’s exposures, outcomes and effects sizes. Some studies analyzed more than one exposure.

Figure 2

Summary data for each exposure group (with effect estimates and confidence intervals). *= confidence intervals derived from O-value. †= NB: Higher Work time control was associated to a lower risk, as expected.

Dose–response associations to risk of occupational injuries were found for length of contract, multiple jobs and work time control (WTC), as follows: the higher the level of WTC, the larger the decrease in risk (28). A shorter contract was associated with an increased risk of injuries compared to a longer contract (14). The greater the number of jobs a person had, the larger the increase in risk of occupational injuries (15).

Only three studies provided gender-stratified analyses. The results among these regarding gender differences in associations were not consistent; women holding multiple jobs had a higher risk of occupational injuries than men in the same situation (21), while the difference was reversed in the case of temporary agency workers (22). Among those paid by the hour, the gender differences were very small (29). The two studies that showed lower risks of injuries for part-time workers were both among healthcare workers; one of them was based on an all-female population (19) and the other one on a population where the men:women ratio was approximately 1:17 (18).

Discussion

Main results

The aim of this review was to collect and summarize existing research on the relationship between precarious employment and occupational injuries. Studies of sufficient quality that matched our inclusion criteria were found (N=17). The articles explored different dimensions of precarious employment, and the results showed – with some exceptions – a positive relation between precarious employment and occupational injuries.

Because of the large variation in exposure and outcome definitions as well as measurement methods, a meta-analysis was not feasible. However, when grouping similar exposures together, the risk for occupational injuries was consistently higher for those performing multiple jobs compared with one (15, 16, 20, 21) and among those employed through a subcontractor at the same worksite or staffing agency (14, 22, 23). The latter has also been found in a research report by the Swedish Work Environment Agency, which did not the meet the peer-reviewed criteria for inclusion (30).

Temporary employment

Temporary contracts were by far the most common exposure studied in the included reports and have previously been reviewed by Virtanen et al in 2005 (9). Holding a temporary contract is a central dimension of precarious employment as it can reflect job and economic insecurity, a lack of occupational experience and possibly also a lack of safety training and workplace introduction from the employer. Temporary contracts are, however, closely related to young age and short job tenure, two known risk factors for occupational injuries. Few studies have attempted to disentangle these factors, which may explain why it is difficult to draw firm conclusions about the associations. In the study by Benavides et al (26), the increased risk of occupational injuries associated with temporary contracts (compared to permanent contracts) decreased substantially but did not disappear entirely after adjustment for length of employment. This suggests that there could exist an independent effect of temporary contracts, separate from the covariation with age and work experience. Future studies should attempt to differentiate the effects of these exposures.

Working hours

Another important temporal factor is the number of hours worked. Temporary workers are commonly believed to work fewer hours at one workplace, which could be associated with a lower risk of musculoskeletal injuries from heavy manual labor if there is more time for recovery. This is suggested in a study by Thomas et al on part time workers (31). However, temporary workers might also work longer hours or have multiple jobs, which are known risk factors, while on the other hand gaining work experience which is associated with a lower risk of occupation injuries. Adjustment for total working hours on an individual level and in the denominator for estimation of population risk (eg, per million hours worked) is therefore important irrespective of which exposure is studied but especially in the case of part-time work.

Bias in outcome measurement

Bias in outcome measurement is illustrated by the somewhat paradoxical finding that unionization is a risk factor for occupational injuries. Unions tend to emphasize security training and permanent jobs, which arguably should lead to a lower rate of injuries. However, the two studies that included unionization/union memberships as exposures showed the opposite. One possible reason for this is reverse causality: workers have been motivated to organize in workplaces that are more dangerous. And while the union may help somewhat, the increased hazard from the basic work processes remains and will result in an apparent positive association. Another possibility is that employees at unionized workplaces are better informed about rights and that the union representatives encourage employees to report injuries and seek compensation. Such an argument would be legitimate in the study by Kubo et al (17) where data was collected through registers, and to a lesser extent in studies where unionization and injuries were both self-reported, such as Berdahl & McQuillan (27). A possible explanation could be recall bias because of the unionized workers’ supposed higher tendency to report an injury, which may also make the injury easier to remember. Self-reporting also often means self-selection, which is another form of selection bias (32).

Using register data also has its limitations. Several studies define outcome as one or more days of absence due to an injury, which is problematic when studying precarious employees who may be contracted by the hour or day and might thus not qualify for payed absence. The lack of benefits might actually be a strong incentive to be present at work, even when sick or injured (6). In summary, these issues could lead to an underestimation of the risk for occupational injuries associated with precarious work.

Gender

It is well known that men more often than women are employed in occupations where the risks for acute injuries are highest, such as construction, farming and heavy manual labor. According to the Swedish injury database, 80% of those seeking emergency care for occupational injuries are men. Of the studies included in this review that provided a gender analysis, it was suggested that women’s risk of work-related injuries was higher among multiple job holders but lower among temporary agency employments compared to men. These findings could be due to the differences in gender distribution across occupations since working at a temporary agency is more common in, for example, constructional occupations (18, 19, 33).

Strengths and Limitations

Search strategy and publication bias

This review applied a wide definition of precarious work in order to identify as many relevant articles as possible. Three major scientific databases were used in order to cover most scientific areas. A limitation to this review is that it only included published articles in peer-reviewed journals. Because all developed countries have at least one register of occupational injuries, there are most likely several high-quality reports from national and international agencies published as non-peer-reviewed reports in different languages that could not be assessed.

Some of the studies made no distinction between injuries and illnesses and were therefore excluded, even though the results of the papers may otherwise have been relevant.

Publication bias has not been assessed in this study, as the heterogeneity of the studies makes standard methods such as funnel plots uninformative. However, as the results of included studies analyzing similar exposures were not homogenous the risk of any major publication bias may be considered moderate; a view that is also supported by the low involvement of commercial actors in this area of research.

Design issues

Given the cross-sectional design of most of the studies in this review, some potential time-related biases must be considered. Because of the difference in time windows used for exposure and outcome respectively in some of the studies (three months of injuries and one week of employment), a person who had a severe injury two months prior may be unable to work in more than one job (decreasing the risk numbers). If that same person was unemployed at the time of the interview, the injury would not be counted at all in the sample of the study (healthy worker effect). In order to avoid these issues and determine the nature of causality, more studies with longitudinal designs are needed.

Precarious work as exposure and implications for future studies

In performing this review, we only found one study explicitly aimed at investigating precarious career trajectories (34). The differences in results for different exposures also underlines the importance of developing methods to define and measure precarious employment and its various dimensions in a non-binary and inclusive way, as suggested by Benach et al (5). Precarious employment is, however, still a term that lacks an accepted standard definition and different areas in academia use different definitions. This should not discourage research, however one should strive to include as many dimensions of precarious employment as possible. There are newly developed constructs and questionnaires such as the Employment Precariousness Scale (EPRES) which measures several dimensions of precarious employment simultaneously, also for multiple job holders (5), which is a group found to be consistently at high risk for occupational injuries in this review. Despite focusing this review on a well-defined health outcome, we found a large heterogeneity between studies. It is likely that the various dimensions of precarious employment bear different weight on health outcomes and also act through different sociologic and physiologic pathways. These would further be dependent on which particular health outcome is studied, but also on contextual factors such as country and industry. It is also possible that some dimensions, such as temporary employment contract is merely a proxy for organizational tenure, as outlined above.

Relevance

The research area on precarious employment and occupational injuries is still relatively new (although growing), as indicated by the limited number of studies found and included in this review.

Some studies were based on large and broad cohorts (15, 16, 21, 26–29) which is a strength, as large and well-selected samples increase the generalizability of the results.

Although the data used in the studies were often 20 years old, the results should be valid today as many of the exposures have not changed: the norm of what constitutes “standard employment” is still permanent a full-time position in most countries, and has arguably changed very little during the last decades. It is conceivable though that the experience of having a precarious employment has become harsher because of the rising rates of unemployment and deconstruction of social welfare in many Western countries. Such structural changes in society are likely to have adverse effects on public health, and incidence of occupational injuries should arguably be viewed as a part of that. It is probable that the development towards a more flexible workforce lowers the employers’ incentive to invest in occupational health at the workplace. In that way, the reduced costs for the employers are indirectly paid with the health of the employees. Regarding health outcomes, it is even questionable if having a precarious job is better than no job at all (8).

To improve work-related health on a structural level it is of greatest importance that policy changes are guided by scientific evidence, and it is the authors’ hope that this review can provide a part of such a body of evidence.

Concluding remarks

The literature included in this systematic review shows an association between some of the dimensions of precarious employment and occupational injuries, but the evidence is still inconclusive regarding many of the studied exposures, such as temporary employment, due to lack of good exposure assessment and adjustment for relevant confounders. Future studies, preferably longitudinal, with high-quality exposure assessments and a multidimensional approach are needed to determine and disentangle this complex relation.