An ageing population creates pressure on economic growth, healthcare systems and social programs (1). This in turn creates a political focus on ensuring as many people as possible are in work, including cancer survivors. Having cancer survivors return to work is increasingly relevant as in recent years cancer treatment has improved, increasing the survival rate (2). In the Nordic countries, more than one in three people diagnosed with cancer are of working age (between 20–64 years old) (3). Furthermore, work has been shown to be highly significant to a person’s identity and social role (4). Despite this, there are no Danish practice guidelines focusing on supporting cancer survivors in returning to work. Furthermore, there are no studies concerning the experiences of Danish cancer survivors who return to work, which may be influenced by the Danish social security system, labor market models and policies.

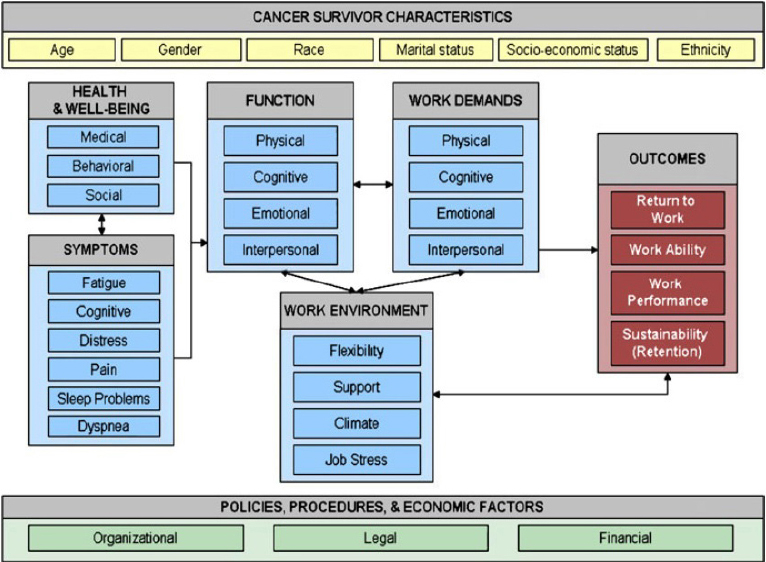

Feuerstein et al’s Cancer and Work Model (5) (figure 1) may provide a framework on which to develop practice. The model was constructed on a systematic search of international quantitative literature and is meant as a tool to support evaluation, prevention and management of work-related problems among cancer survivors including return to work (RTW). The model illustrates multiple factors at personal, micro-, meso- and macro-levels with a reciprocal relationship that could influence cancer survivors work outcomes.

Figure 1

Cancer and Work Model. Reprinted by permission from Copyright Clearance Center: Springer Nature. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. Work in cancer survivors: a model for practice and research, Feuerstein M, Todd BL, Moskowitz MC, Bruns GL, Stoler MR, Nassif T et al (2010)

However, according to a qualitative review by Wells et al (6), although the Cancer and Work Model covers some important domains, it does not cover all that are relevant to cancer survivors returning to work. The model is missing a dimension related to the meaning and role of work to the individual. Wells et al suggest that this individual dimension may provide an important basis when developing return to work interventions.

Hence, the main aim of the current study was to explore Danish cancer survivors’ perspectives on returning to work, including the meaning of work to the individuals. The following research question was proposed: how do Danish cancer survivors perceive work and which challenges do they experience in relation to returning to work? Furthermore, a second aim was to discuss the relevance of the Cancer and Work Model in correlation to the study results.

Methods

Approach

This study aimed to address the perspectives of cancer survivors, hence a phenomenological and hermeneutic approach was applied (7). Focus group interviews were chosen as the data collection method because they allow an enrichment of data when the participants comment and elaborate on each other’s accounts and act as a basis for cross-checking and clarifying perspectives (8).

Context, sampling and data collection

Participants for six focus group interviews were recruited during four cancer rehabilitation courses that took place between October-December 2015 at a national rehabilitation center in Denmark. The courses were aimed at cancer survivors who wished to address matters related to RTW. Those who would like to attend the course were accepted if they had permission from a doctor and if they met the inclusion criteria for the course. To be included, the person had to have or have had cancer, be in need of help to manage problems related to cancer (eg, physical, psychological, social or existential problems), be able to participate actively in the course program, be willing to contribute to research, and be able to understand and speak Danish. The residential courses lasted five days and were provided free of charge, including meals and accommodation. The participants found the course by searching the internet or through information, typically from a nurse at the hospital or a local cancer counselling center. Focus groups were held as part of the course schedule but were optional. Participants were informed that participation was voluntary, that findings would be anonymized, and that the interview would be audio recorded and treated as confidential. Everybody who was invited, accepted to participate. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants in the study.

A male social worker (JBT, leader of the rehabilitation courses with several years of experience working in cancer rehabilitation) and a female PhD student (LZ, major in Public Health and trained in qualitative research) took turns acting as either a moderator or an observer. The participants recognized JBT as their course leader but had not met LZ before. Both moderator and observer presented themselves prior to each focus group, explaining their background and reasons for conducting the study. No one but the moderator, observer and participants were present during the focus groups. LZ developed an interview guide containing the following topics: (i) How do cancer survivors perceive work and (ii) What challenges have they experienced in relation to RTW? To allow for diversities and nuances in the participants’ answers to what challenges they have experienced, a third topic was added: (iii) What support have they had or would they have liked to have had in relation to returning to work. There was neither a pilot study nor any field notes made. The focus groups lasted one and a half hours each. All were with different participants.

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Danish National Committee on Health Research Ethics. According to the committee qualitative studies do not require official ethical approval.

Data processing and analysis

The audio recordings of the six focus group interviews were transcribed verbatim and then imported into the computer program NVivo 11 to manage data organization. They were not returned to participants for comments. Meaning condensation (9) was applied to gain an overview and find themes across the data. The first authors carried out condensation and discussed the results with the last author to reach consensus. The condensations were indexed in categories, initially based on a prior understanding (reflected in the introduction of this study) that there is an individual dimension to the meaning and role of work, and there are multiple and varied factors influencing the process of return to work. Next the categories were further developed in a hermeneutic process of moving between analysis and interpretation of the individual parts and the whole (10) before realizing the final themes. All phases of the analysis were discussed with the last author. Participants were not invited to give feedback on the findings in this part of the process.

Results

Thirty-two people participated in the study (see table 1). The participants were primarily women and on average 47.9 years old. The majority were on full-time sick-leave, six were working part-time (temporarily) and one was working 13 hours per week in a subsidized job.

Table 1

Demographics of the participants [NC=neuroendocrine carcinoma; NR=not reported; SL=on sick-leave, PT=working part-time; PS=paid sick-leave; SB=sickness benefits; CB=cash benefits; SES=state education support]

The analysis of data provided three overall themes.

A new perspective of work

The first theme shows that the participants were motivated to return to work but their perspective of work had changed following their cancer diagnosis. This had caused new aspirations priorities and concerns to arise. Many did not imagine themselves resuming work in the same way as before they had cancer.

In all six focus groups, the participants said that having cancer had made them reconsider whether their job was right for them, or in which way or how much they would like to work, or how work had lost or gained some of its importance compared to other aspects of life. The accounts differed from some wanting to make a few changes to their job to others who wanted to completely change jobs. A few stated that they had realized they had just the perfect job. One participant explains:

“When I was told that I was incurably ill, […] I thought about what to do with my life and then I thought, I would really prefer to keep living like I do and most of all I hope that I can work. Always. That it means a whole lot to me. It was really…If I didn’t know, how much I loved my job, then I certainly found out.” (Susanne)

Some participants were driven by aspiration: they had realized that they would like to work with something that they believed would make them happier than their former work or they wanted to spend more time on activities outside of work. Others had concerns: they thought that the physical and cognitive effects of their cancer and/or cancer treatments meant that they would not be able to perform the same amount of work or the same type of assignments as before.

Therefore, colleagues and employers cannot assume that the cancer survivor will continue working as they did before they had cancer:

“In some way they have to get to know me again. On my part I have to communicate that I’m different now, that maybe there are some things I could do before, that I won’t do again, that there are some things I look differently at now. So somehow it’s like starting all over again.” (Ellen)

Missing support in the process of returning to work

The second theme shows that some participants had supportive job consultants while others had the opposite. Many were left with questions of how to navigate the bureaucracy they encountered through their contact with the municipality. This caused them to worry.

What most participants reported about this period after treatment is that they had a lot of questions, most of which were directed at the municipality. As the municipality is responsible for paying sickness benefits and managing the initiation of vocational rehabilitation (11) the participants needed to adhere to the municipalities’ rules. Rules that some participants found unnecessary, confusing and complicated. They were anxious about losing their entitlement to sick-leave and/or uncertain of their economic situation. A participant explained:

“Then, I remember, there was something about a possibility of getting a prolongation of the sickness benefits. I was so terrified because she was talking as if it wasn’t a given to be prolonged. I never understood completely, what it would mean not to be prolonged, right. I was so scared that suddenly I wouldn’t be allowed my salary or something like that, right.” (Heidi)

A few participants stated that the job consultants were not interested in their needs but merely interested in getting their clients to work in order to save money. Moreover a couple of participants felt that they were on their own protecting themselves from job consultants and employers who were eager to have them working.

A group of participants had positive experiences with the municipality job consultants. They talked about consultants who were protective, telling them not to start working to soon, and focused on the individual’s needs. They reassured them that they needed not to worry about rules, that they had time and would not be rushed. This was greatly appreciated by the participants. One explained:

“But that thing when you’re accepted when you say that we need to take it slow, I mean that is what the employer and the public sector can do to help […] That, I really think, is a good help.” (Mona)

Furthermore, a few participants questioned why the municipality was involved in the first place in the RTW process since these participants saw no need of this.

Uncertainty of how to become and when one is ready to work

The third theme shows that it was difficult for the participants to predict the course of their recovery and know when they would be ready to work again. They would like to receive help to understand when they would be ready and also to be prepared to work.

A lot of participants worried about how the physical and cognitive effects from cancer and/or cancer treatment would affect their ability to handle their job. They experienced fatigue, loss of memory, loss of concentration, or felt physically weak. Some were concerned about the amount of hours they would have to work, others about the quality of work they would deliver or the responsibility they would have. It seemed especially worrying to the participants whose jobs involved a responsibility for others’ health or lives. A midwife explained how she really wanted to feel fit both mentally and physically before she made life and death decisions. And a healthcare worker was concerned that in her job she would be handling medication:

“If anything goes wrong with drug distributions, then it isn’t candy I’m dealing with, you know. It’s an anticoagulant or…It’s a huge responsibility and I’m not sure I can carry that burden.” (Camilla)

For many of the participants, becoming ready to work was not something that happens automatically. Hence some wished to have guidance in how to become ready and how long to expect the process to take, likewise others wished to be offered physical and/or mental rehabilitation courses readying them for work. One participant stated:

“All I want is to have a process made, so that I can return well to the job market and not collapse […] It means everything that I can experience a success and it is something that I can present when we are going to have the meeting about how and when I can start. I wouldn’t be plucking out of thin air and say that maybe it’s doable.” (John)

Discussion

The main aim of this study was to explore Danish cancer survivors’ perspectives on returning to work.

The study has provided three themes, Danish cancer survivors: (i) do not imagine themselves resuming work to the same extent as before they had cancer, (ii) are missing support in the process of returning to work, and (iii) are uncertain of how to become and when they will be ready to work.

Our findings align with previous studies. The concept that the meaning and role of work to the cancer survivor is important is found in other reviews (12, 13). The problem of missing support from professionals whose purpose is to help the cancer survivors return to work is also documented in studies (14–16) as well as cancer survivors’ need for advice (15, 17). Still, the uncertainty of how and when to return to work seems to be less evident in former studies. At the same time the key role that employers are given by respondents in other studies was not a result in this study. As described, the collaboration with the job consultants were experienced as a main barrier. The Danish welfare system secures certain rights in relation to keeping a job, but people still need to negotiate these rights with job consultants.

A second aim of this study was to discuss the relevance of the Cancer and Work Model (5) in correlation to the results of the focus group study. It seems that the model covers most of the relevant issues for Danish cancer survivors. The concepts of function versus work demands and work environment are in play when the participants’ worry about their ability to deliver quality work or are pressed to work more hours than they feel able to do. Further, the concepts of policies and procedures are highly relevant. The participants report of too many rules to deal with while on sick-leave. Some tell how they feel that the municipality is not on their side. This is unfortunate as the purpose of the system is to help them.

Hence, our study confirms the importance of the domains illustrated in the Cancer and Work model. Our study also confirms the importance of the dimension of “meaning and role of work” to the individual derived from the qualitative review of Wells et al (6) It seems to be a very significant factor to Danish cancer survivors. Only a few would like to return to the same job and/or the same tasks as before they had cancer. For the ones who cannot return to the same job because of reduced level of function this would be covered by applying the Cancer and Work Model.

By combining the Cancer and Work Model (5) with the individual dimension suggested by Wells et al (6), issues relevant to Danish cancer survivors in the process of returning to work will be addressed. However, the theme demonstrating that cancer survivors are uncertain of how to become and when they are ready for work is new compared to earlier studies and would be absent in the combined model. This is a crucial issue to deal with when supporting cancer survivors and probably not unique to Denmark.

In order for the trustworthiness of this study to be judged, we have strived to present enough detail for the reader to understand our methodological and analytical choices and the presented conclusions (19). It is important to note that the participants in this study had all signed up for a course for people who would like to return to work. This was reflected in the fact that in general the participants expressed that they were motivated to return to work. Another circumstance worth noticing is that in our sample there were mostly women with breast cancer which corresponds to breast cancer being the most common cancer type among women and women being overrepresented in rehabilitation courses. Including more men and cancer types might have changed the findings.

The next step will be to write the guidelines based on our findings and to test their feasibility in practice. There is a challenge in forming guidelines that support the uncertainty of how and when to be ready for work, since there is a contradiction between the two. Inherent in guidelines is a wish to plan and practice in an efficient way, which may be in contrast to the uncertainty that cancer survivors experience in the process of returning to work. The contradiction between general standardization and individual uncertainty is described in medical anthropology (18). It would be interesting to develop this concept further in return to work-research.

Concluding remarks

In conclusion, our study has shown that Danish cancer survivors change their perspective of work. They are motivated to return to work but do not want to resume duties as before they had cancer. At the same time, they experience barriers when engaging with the public sector ‒ which is designed to help them ‒ and they are challenged by not knowing the trajectory of their recovery from treatment or when they will be ready to work. Except for the latter two, these issues would be covered if practice guidelines supporting cancer survivors returning to work were based on the Cancer and Work Model and included a dimension related to the meaning and role of work for the individual. To also cover the uncertainty of how to become and when one is ready to work, we recommend that Danish and international practice guidelines address these issues.