Technological progress, shifts in economies, and an increased mobility of capital and workers over recent decades have transformed employment conditions (1, 2). Labor markets have witnessed a transition where new and more flexible forms of employment are replacing so-called “standard” forms of employment, generally associated with full-time, long-term, and secure jobs with entitlement to benefits (3, 4). While on the one hand, the increase in labor flexibility has been considered to have a positive impact on economic growth, on the other hand, it has contributed to a growth of atypical forms of employment of lower quality with potential adverse consequences, often referred to as precarious employment (PE) (5). PE is increasingly being recognized as a threat to health and well-being of workers and their families (3, 6) and is associated with mental and physical health (7, 8) as well as occupational injury risk (9). Mechanisms by which PE harms workers’ health are largely unexplored (10, 11). Some researchers have developed multidimensional models and constructs of PE and examined the pathways and mechanism by which these are associated to health outcomes (6, 12–14).

Despite several attempts, there is no consensus on what constitutes PE and the various constructs or concepts used to describe it have greater or lesser currency depending on country and context (4). There is confusion when it comes to defining PE, as many related terms are used interchangeably: the precariat, precarious employment, precarious work, or simply precarity or precariousness. In the EU, the terms “atypical” or “nonstandard” forms of employment have been used extensively when referring to PE, while in the US the term “contingent work” is more common (4). The lack of a common definition severely hampers the comparison of studies and consequently reduces the applicability of research findings, despite high societal relevance. Leading researchers in the field have called for the development of a common definition based on objective measures (10, 15). PE is a term that has undergone substantial theoretical development and gained international traction over the last decades in many countries and research disciplines. There is a lively debate on how to define it, which is the rationale for limiting our work to PE specifically and deliberately excluding other concepts (16).

In order to support such an effort, we believe that a systematic review across disciplines of the available definitions of PE could lead to a better understanding of how PE is conceptualized and operationalized. Each research field approaches PE differently, therefore a classic Cochrane-style review is not appropriate. A synthesis and analysis of both qualitative and quantitative studies can promote a deeper understanding of this complex phenomenon, which will further advance for subsequent research on PE.

The aim of this study is to investigate how PE has been defined within research by reviewing the literature for definitions and operationalizations of PE and identify the construct’s core dimensions in order to facilitate guidance on its operationalization.

Methods

Before conducting the review, a protocol was adapted from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (17). During the process, guidance and standards were also followed from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (18). The full protocol can be found as supplementary material A (www.sjweh.fi/show_abstract.php?abstract_id=3875). This study is part of a larger project, with a published study protocol (19). Systematic review methods are well-developed when it comes to quantitative research studies, while methods for systematically reviewing a combination of both qualitative and quantitative research are still emerging and under development (20, 21). In this study, we have drawn on these methods also adding other qualitative methods to achieve our aims (see below).

Search strategy and eligibility criteria

The literature search was conducted in two multidisciplinary bibliographic databases: Web of Knowledge (all databases including the Web of Science Core Collection and MEDLINE) and Scopus.

We included any type of original publication (book, journal articles, conference proceedings etc.) of any type (observational, intervention, methodology, theory). Our exclusion criteria were (i) language other than English, (ii) lack of an explicit definition or operationalization of PE, and (iii) non-original research, such as systematic reviews or discussion papers. No restrictions were applied on year of publication, population or research discipline. We did not apply inclusion criteria related to quality of the publication. However, in the analysis, we considered the strength of both theoretical and empirical foundations of the different definitions and operationalizations. The search strategy was constructed using the same key words in both databases and by screening titles and abstracts. The key words were all related to or constructed from “precarious employment”, using a spectrum of key words in order to allow a potentially broad inclusion of studies. In order to test the selected key words, pilot searches were conducted prior to the final search. The final search strings were the following:

WEB of Science: TI=(precari* AND (employ* OR job* OR work*)) OR TI=(precariat OR precarity)

Scopus: TITLE(precari* AND (employ* OR job* OR work*)) OR TITLE(precariat OR precarity)

Study selection and data collection

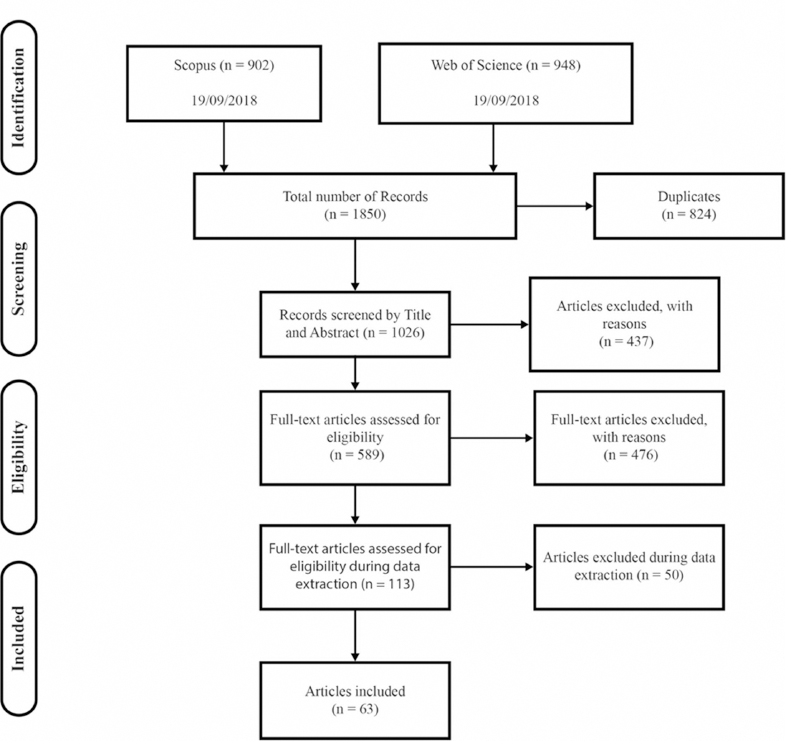

Figure 1 illustrates an overview of the selection process of the articles. The two database searches resulted in a total of 1850 records, which were downloaded to EndNote reference manager software. The software was then used to remove duplicates (N=816). Citations were thereafter uploaded to the online Covidence systematic review management software, which is the standard production platform for Cochrane reviews (Covidence systematic review software VHI, Melbourne, Australia). Firstly, this software was used to identify additional duplicates (N=8), leaving 1026 unique records to be assessed. Secondly, the first author screened titles and abstracts for relevance, and 437 studies were excluded because they did not match any of the inclusion criteria, leaving 589 hits to be screened in full-text for eligibility against the predefined exclusion criteria. Full-texts were retrieved through the online library resources. Authors and/or publishers were directly contacted if studies were unavailable through the library. Out of the 589 hits, 476 records were further excluded as not being an original or peer reviewed article (N=220), not stating a definition of PE (N=239) or not written in English (N=17).

Two reviewers assessed and extracted data from the remaining articles (N=113). If inclusion of an article was uncertain at this point, it was kept for the data extraction stage, which was conducted using an online google form developed by the authors, a method successfully used in previous reviews (8, 9). (Supplementary material B.) The form also allowed the reviewers to suggest the exclusion of an article and provide the reason for this. Article review and data extraction of each study was independently conducted by two of the nine reviewers. At this stage, an additional 50 records were excluded, leaving a total of 63 studies for the final analysis (12, 22–83). The main reason for exclusion at this stage was that articles had used PE as a theoretical framework for their study but did not properly define it in their research. In 35 studies, the reviewers had a disagreement with regard to inclusion/exclusion. The first and last authors re-examined and discussed jointly these articles until consensus was reached. All differences in the data extraction were resolved in the same way.

Data analysis

Quantitative and qualitative analyses were performed separately on the included articles in order to approach the complex multidimensional nature of PE.

Descriptive analysis

Descriptive data on study characteristics were extracted from the articles included in the review. These included: country of study, main outcome of the study, and the full definition of PE including separate extraction of each dimension in case the paper used a multi-dimensional definition. We used these data to present summary statistics for some important characteristics of the included studies. These were: region, research area, study design, primary outcome of the study (if any), type of PE definition, definition of PE created on an existing one, and number of dimensions of PE.

Qualitative analysis

A thematic-analysis approach – a widely used qualitative data analysis method focused on identifying patterned meanings across a data set (84) – was used to analyze the collected definitions and operationalizations, and consequently generate dimensions of PE. This approach involved three main steps with some overlap. In the first stage, after the descriptive analysis, a free line-by-line analysis of each PE definition and its dimension(s) was performed, and these were grouped into similar subthemes. Initially, these subthemes were kept as similar as possible to the meaning and wording of the original definition. In a second step, the subthemes were then examined and broader patterns of meaning were identified, and the subthemes grouped into aggregated themes with short descriptive labels, sought to describe each theme in one or a few words. Finally, several rounds of discussions were held among the authors to reach consensus on which subtheme should be designated to which theme and how these themes should be clustered into what we will henceforth call dimensions of PE. Inclusion or exclusion of the dimensions was then guided and based on a theoretical framework for PE developed by Bodin et al (16).

Theoretical framework

We anticipated that our thematic approach could generate dimensions that would fall outside the common understanding of PE and decided, a priori, to apply a theoretical framework to guide our analysis in the exclusion of such dimensions. The aim of the framework is to understand PE as a multidimensional construct where unfavorable features of employment quality accumulate in the same job (16). This framework builds on previous work by several leading researchers in this field (6, 12, 13, 85–87), and locates PE at the level of employment relationships to include salary, working times, contractual relationship and rights. Employment relationships, especially rights, are usually defined by laws, regulations and collective agreements. Social support through family and welfare systems are factors that very well might influence both the bargaining position of the workers as well as feelings of (in)security. As such, we believe that social support and the welfare state could be best seen as contextual or modifying factors. It also follows from our theoretical framework that boring, unsatisfying (88) low-status or hazardous work (89) should be seen as possible consequences of PE but not a defining characteristic. The same holds for health outcomes and job insecurity as a psychological (cognitive and/or affective) phenomenon as well as social precarisation (poverty, etc). This theoretical framework thus includes neither health consequences of work nor the related social or psychosocial concepts that might relate to quality of work. Both employer and employee are seen in broad terms, as these roles can take on a variety of legal and organizational forms in the ever-changing economic environment of gig and platform work, outsourcing and consulting.

Results

Descriptive analysis

Of the 63 research articles included in the review, the largest number were conducted in Europe (table 1). Canada (N=9) and South Korea (N=9) were the most common countries where studies were based. Other countries where ≥3 studies took place were Italy (N=6), Australia (N=6), and Spain (N=4). Several studies (N=7) were conducted in multiple countries. Research disciplines were defined a priori in the online google form developed by the authors and an option to add a discipline was given if the discipline was not listed. The most recurrent were respectively public, environmental or occupational health (N=29) followed by industrial relations (N=17), sociology (N=5), and economics (N=3). In all, 43 studies were quantitative observational studies (12, 22–63), while 18 were qualitative studies (64–81). Only one article conducted a mixed-methods approach (83) and one was an historical article (82). In 16 publications, definitions of PE were based on one or several pre-existing definitions in the literature (23, 32, 36, 42, 43, 58, 61–64, 69, 71, 72, 75, 78, 79). These included works by Amable (90), Benach et al (7), Burgess & Campbell (91), Kalleberg (92), Paugam (88), Piore (93), Rodgers (94), Standing (95, 96), Tompa et al (89), Tucker (97), Vives et al (12) and Vosko (98, 99). In the rest of the articles, the author(s) had either developed their own constructs based on theory, with no clear reference to previous work by others (although often inspired), or defined PE based on the availability of data either with or without reference to theory. When analyzing the number of dimensions used to define PE, 12 studies used only one dimension, 11 studies used two dimensions, while 40 were based on ≥3 dimensions.

Table 1

Number of included studies according to study characteristics.

| Characteristics | Studies (N) |

|---|---|

| Region | |

| Europe (including Turkey) | 24 |

| Asia | 14 |

| Oceania | 12 |

| North America | 7 |

| South America | 3 |

| Africa | 3 |

| Multiple continents | 0 |

| Research discipline | |

| Public, environmental or occupational health | 29 |

| Industrial/labor relations | 17 |

| Sociology | 6 |

| Economics | 3 |

| Other (demography, ethnic studies, law, ethnography) | 8 |

| Study design | |

| Quantitative | 43 |

| Qualitative | 18 |

| Other a | 2 |

| Type of precarious employment (PE) definition | |

| Theory based | 23 |

| Ad hoc (data-driven, by convenience or limited by available data) | 22 |

| Combination of theory based + ad hoc | 13 |

| Empirical (PE definition was the result of the study) | 2 |

| Unclear | 3 |

| Number of dimensions of PE | |

| 1 | 12 |

| 2 | 11 |

| 3 | 15 |

| 4 | 8 |

| ≥5 | 17 |

Qualitative analysis

In total, our thematic-analysis resulted in five dimensions: (i) employment insecurity (ii) income inadequacy, (iii) lack of rights and protection, (iv) work environment, and (v) health effects and social consequences (table 2). Following the above-mentioned theoretical framework, we considered the definition of PE as dependent on characteristics of the employment relationship. Consequently, the two latter dimensions were excluded from consideration and were considered as possible consequences of PE but not as unique to or defining of such employment (supplementary material C). Thus, in the following sections we first focus on the three included dimensions of PE, derived from 145 extracted subthemes aggregated into ten themes (figure 2), followed by the excluded dimensions.

Table 2

Summary of the three dimensions of precarious employment (PE) and the themes identified in this study.

Included dimensions

Employment insecurity. In this first dimension, four major recurrent themes were identified: (i) contractual relationship insecurity, (ii) contractual temporariness, (iii) contractual underemployment, and (iv) multiple jobs/sectors. Overall, 73 of the 145 subthemes, focused on different contractual aspects of PE in both qualitative and quantitative studies.

Contractual relationship insecurity was a predominant theme that emerged from the analysis. A person can be directly employed, employed through an agency or self-employed as well as being employed in other indirect ways depending on context. In the quantitative studies, being employed through an agency or being self-employed was usually contrasted to being directly employed (23, 27, 28, 31, 34, 49, 51, 57). From the analysis of the qualitative definitions, it was possible to capture the negative connotations associated with some of these subthemes, although no explicit comparison was made. For instance, being employed through an agency was described as the only choice available and was related to personal negative experiences (67, 82).

The studies investigating contractual temporariness focused on whether the person was employed on a fixed term contract or a permanent contract (25, 26, 29, 30, 39, 40, 47, 48, 52, 53, 56, 57, 82, 100). There was substantial heterogeneity in how these two concepts were defined. Within fixed term contracts, some studies included “on demand” contracts as well as seasonal employment (22, 32, 33, 100). Other times fixed-term contracts were identified by contract duration, with inconsistency as to length, ranging from longer than a month but shorter than a year, to contracts lasting <3 months or only a month (12, 36, 39, 61, 62). Insecurity deriving from fixed-term contracts and not knowing if, for how long or when these contracts were going to be renewed, was the major feeling experienced by the workers and described in the qualitative studies (67, 70, 73, 74, 81). Another way to consider the meaning of a fixed-term contract is to contrast it with the existence of stable job relationship between employer and employee. Giraudo et al (30) distinguished between number of working contracts and number of jobs held by a person in order to capture frequency of job changes, for instance if a first apprenticeship contract was followed by a permanent contract.

Contractual underemployment is represented by part-time versus full-time contracts. In some studies, part-time contracts were operationalized as having a contract guaranteeing <34 or 35 hours per week (39, 53). One study further specified part-time as working ≤35 hours/week with a contract lasting ≥1 month (39). An aspect emerging from the analysis of these subthemes was involuntary part-time working, where part-time employees explicitly indicated that they were unable to find full-time work, therefore they would accept a part-time position (32, 33, 45, 46). Contractual underemployment does not include skill underemployment.

The subtheme multiple jobs/sectors was operationalized differently across studies but was described as either holding >1 contract or job or >1 job in different economic sectors (30, 32, 33, 46). None of the studies specified if these jobs or contracts were held simultaneously or for instance accounted for the total number of jobs held by a person within a year. One study operationalized this variable as any person holding a second job (46), while another further investigated the number of economic sectors in which a person was working and identified precarious workers in three different groups: those who on average work in three, four and more than four different jobs in two different economic sectors (30).

Income inadequacy. Even though this dimension encompasses only one theme – income level – there is a high heterogeneity in how studies have defined and operationalized this variable. Income level was mainly investigated as hourly wage, monthly salary, or annual income (12, 27, 36, 43, 59–62). One study made a distinction between direct and indirect income in order to be able to differentiate between wage and any supplementary income derived from other sources, such as government transfers and government- and employer-sponsored benefits (75). In all studies, to characterize income inadequacy, a low income level was set depending on the specific context and country, usually relating to national standards for minimum wage, poverty line or median income (44, 54, 58, 59, 78). Qualitative studies described the high feeling of uncertainty and insecurity deriving from a low income, as well as its inadequacy to provide stability (65, 83). They further highlighted physical and mental health effects, as well as poor living conditions related to a low and unstable salary (70, 77). Although “income volatility” was not derived as an explicit theme during the thematic analysis, the included articles highlighted unstable and inconsistent income as related to PE (65, 78).

Lack of rights and protection. Four main themes were related to this dimension: (i) lack of unionization, (ii) lack of social security, (iii) lack of regulatory support, and (iv) lack of workplace rights. These themes emerged in 26 articles with high heterogeneity among definitions and operationalizations in subthemes and, mainly due to diverse socio-economic and legislative contexts across countries.

Lack of unionization was primarily investigated as the existence of trade unions in the specific country under investigation and/or if the employees were in fact covered by a union (27, 58–60). An important feature emerging here is how workers’ representation has declined over the years and how, in contrast, unionized workers have less risk of arbitrary dismissal compared to not unionized workers (27, 69).

When it comes to lack of social security, articles often did not specify how they accounted for and distinguish between in-work (employment) benefits and government determined social security benefits (53, 60, 71).

Two studies further distinguished between whether participants received medical insurance and social insurance (44, 60). This goes hand in hand with lack of regulatory support for full benefits, where the effectiveness of labor policies and labor standards were questioned (64, 69, 76, 82). Studies also investigated whether workers had access and/or power to exercise workplace rights such as, protection against unfair dismissal, protection from authoritarian treatment, discrimination or harassment (12, 36, 60, 78, 83). Other studies mainly looked at the effect of lack of workplace rights, from unacceptable working practices, forced labor and inability to demand better working conditions (12, 36, 61, 62, 66, 81).

Excluded dimensions

Work environment. This dimension consisted predominantly of themes and subthemes concerning psychosocial work environment such as lack of work-time control (schedule unpredictability) (53, 58, 66, 68, 70, 80), high work demands (long working hours) (42, 43, 46, 53, 66), skill discretion (being able to use and develop one’s skills) (42, 45, 46, 53, 60, 65, 68, 72), as well as hazardous physical work environment (58, 60).

Health and social consequences. In this dimension, diverse themes were collected with the common features that they fall outside the realm of employment and work. The two most dominant themes in this dimension were health outcomes and social deprivation (46, 53, 62, 65, 70, 77). Social support was also a theme derived from a small number of studies (62, 67, 77).

Discussion

This systematic review shows how PE was defined across 63 studies from four different continents. Three overarching dimensions of PE emerged from the thematic-analysis: employment insecurity, income inadequacy, and lack of rights and protection. These three dimensions should not be interpreted as an attempt to launch yet another multi-dimensional definition of PE but rather as an organized summary of previous and present definitions and operationalizations. From the large number of screened studies, it is evident that researchers usually do not define or operationalize PE, despite being a term without a commonly accepted definition. The most common research discipline included in this review was Public or Occupational Health, where clear definitions of PE as an exposure are needed in order to design etiological studies of PE’s effects on health. On the contrary, the full list of retrieved publications before screening was dominated by labor market studies, sociology and economics. Furthermore, even though most researchers today acknowledge PE as a multidimensional concept, most of the academic and public studies still apply unidimensional definitions or operationalizations, focusing predominantly on income level or employment status where long-term or full-time contracts are considered as non-PE.

Elements for a multidimensional concept of PE have appeared in the literature. Rodgers & Rodgers definition from 1989 underlined the importance that employment instability and insecurity play in PE (94). This is very similar to the derived dimension “employment insecurity”, emerged from the reviewed studies that highlighted how contractual employment arrangements evoked feelings of insecurity and instability directed towards the future (67, 70, 73, 74, 81). Many studies looked at contract status as the only indicator for PE (25, 26, 31, 34, 37, 38, 41, 47, 48, 51, 52). We concur on the importance of contract status but suggest that focus should be put on duration of the contract into the future from the time-point it is measured, rather than looking at tenure. When considering multiple jobs/sectors, we further propose that questions measuring contract renewal unpredictability could be developed to account for those on recurrent fixed-term contracts.

The second dimension derived from the analysis – income inadequacy – reflected salaried work, a dimension which has been included with little variation in all theory-based definitions of PE we have come across (12, 27, 36, 44, 54, 58–62, 65, 75, 78). There is however, a debate as to whether income inadequacy should be measured solely on the individual’s salaried work and benefits or should also account for either employment-related income protection such as sickness or unemployment benefits and/or household income (54, 65, 75, 101, 102). None of the studies in this review considered income from work-related benefits or insurance (sickness absence, unemployment etc.). Household income however is not determined by the employment relationship and should in our opinion be seen as a social protection scheme with variable importance depending on the context. A second aspect we believe relevant in this dimension, which derived from discussion among the co-authors and not from the reviewed studies, is income volatility. Two qualitative articles included in this review showed the high extent to which having an unstable and inconsistent income when precariously employed, affects someone’s life (58, 65). The coherence of income volatility suggests the need to consider how volatile an individual’s income is across months and years. Volatility could be very significant when estimating how stable or unstable employment is, and this can be further enhanced by looking at the direction of this volatility (income gain or loss) (103, 104). Studies not included in the review have shown how income volatility may be linked to an increase in job displacement and that it can reflect both unemployment/re-employment transitions, as for instance being in and out of involuntary part-time work (105, 106). While many studies have linked low income and adverse employment change to poor physical or mental health outcomes, income volatility and its public health consequences are yet to be explored (107, 108).

The last identified dimension, lack of rights and protection, is present in many PE definitions that aimed to investigate degrees of employment insecurity, employment quality and precariousness (27, 94, 95, 98). At the end of the 1990s and beginning of the 2000s, PE started to be characterized both as the relationship to instable and flexible employment conditions and by working conditions, such as having a badly paid job or lack of workers ‘rights (109, 110). The key role and implications of union coverage, lack of social benefits, as well as general employment conditions experienced by the worker have been thoroughly investigated by a variety of authors (91, 94, 111, 112). This dimension is highly dependent on the context, which makes it difficult to operationalize in a way that works for researchers in different countries. A clear distinction should be made between individuals receiving social security based on their employment condition and those who receive it with no regard to their employment status. The qualitative studies included here highlight the need for PE workers to receive protection against unfair and authoritarian treatment – such as unjustifiable dismissal, discrimination, sexual harassment, and unacceptable working practices – the feeling of powerlessness to exercise their workplace rights, and mistrust towards the government for not providing support and transparency (36, 65, 69, 71, 78, 81). Rights and protection comprise an especially complicated dimension when studying informal or migrant work. This aspect needs more attention, particularly when considering that in 19 of 23 European countries under analysis, union membership among migrants was lower than among nationals (113).

Strength and limitations

PRISMA guidelines were followed to the extent possible and a research protocol was developed prior to conducting this systematic review. Even though integrating different types of studies and data within the same review remains challenging, we believe that qualitative research can and should be included in systematic reviews. To do so requires, however, that studies included in systematic reviews are of high quality and reliable and that all relevant research is included and conclusions are evidence-based (114, 115). On the other hand, a limitation is that there is yet little guidance when combining different study types in reviews. Studies written in languages other than English and studies using synonyms or other terminology rather than PE were excluded from this review, which risks missing definitions of PE from some arenas. Nonetheless, the included studies were obtained from many different labor market contexts. The thematic-analysis performed on the data and the generation of subthemes and themes is a process of moving from the text under analysis to a higher level of conceptual abstraction.

This implies that the process is very dependent on the authors, which could be a potential limitation. In order to minimize subjective influence as much as possible, several rounds of analysis were conducted among our research group which includes researchers from several different disciplines and countries.

Implications

The debate on PE has become increasingly interdisciplinary and international and varies according to different labor markets, economies, and social systems. There is need for a common understanding of PE in order to understand its role as a social determinant of health. Based on this review, we believe that a common definition is both feasible, attainable, and likely to be useful in several contexts and research methodologies. National political and social contexts do matter when it comes to how and to what extent PE can affect individuals, and this needs to be taken into account. Unconsidered and unchecked, PE could lead to a dynamic transformation of the society as a whole. It is fundamental and important to grasp all its nuances in order to identify groups that are excluded from or find themselves in limbo with respect to being in the labor market. For the foreseeable future, PE is likely to be a permanent feature of our labor market, especially given rapid technological development and its consequences, thus a joint effort across disciplines and countries should be taken in order to keep worker´s health as our main goal.

Concluding remarks

This systematic review did not aspire to present yet another multidimensional definition of PE, rather it summarizes the definitions previously and presently in use. Despite some differences in definitions and operationalizations across researchers, disciplines and countries, the results of this review show that a common definition of PE is likely attainable.