Job dissatisfaction (JD) is widely known to have a negative association with workers’ health and productivity (1–3). Many studies have observed that JD contributes to mental health problems, including anxiety, burnout, and depression (4–7), as well as poor self-rated health (SRH) (8–10), which represent more general health conditions. Studies have also provided evidence of a correlation between JD and more objective negative outcomes in the workplace, such as sickness absence (11–13), health-related job loss (14), and disability pension (15, 16), all of which signify a loss of effective workforce participation. JD can be interpreted as a key mediator of the association between psychosocial factors in the workplace and workers’ health outcomes (6, 7) because it reflects a worker’s subjective assessment of various aspects of the work environment.

However, the observed association between JD and health outcomes is most likely confounded by personality traits (17, 18) and other inherent individual attributes that are likely to vary from participant to participant. For instance, workers with higher neuroticism – that is, those who tend to respond to threats, frustration, or loss with negative emotions – are more likely to be dissatisfied with their jobs and suffer from psychological distress (PD) (17). If this is the case, the observed association between JD and health outcomes may be overstated. Many previous studies that relied on cross-sectional analysis were not fully free from this type of bias.

Another issue to be addressed is simultaneity bias. Health outcomes are affected by JD; however, JD is also likely to be affected by health outcomes, possibly resulting in an overestimated impact of JD on health, as observed in the cross-sectional data (19, 20). Prospective cohort studies are generally expected to alleviate these biases, but follow-up for just a few years after the baseline cannot fully control for the correlations between repeated measurements within each participant.

Lastly, the reverse causation from health outcomes to JD has been largely understudied. Although many studies have investigated the determinants of JD (21–26), health outcomes have usually been treated as a result rather than a cause of JD.

In this study, we examined the association between JD and health among middle-aged workers using longitudinal data obtained from a 14-wave nationwide population-based survey. Unlike most preceding studies, we employed a mixed model analysis (27) to take full advantage of repeated measures for each participant over time. Mixed models can capture both fixed effects (which are assumed to remain the same across participants) and random effects (which are assumed to vary randomly from participant to participant). These models are expected to control for participant-specific factors, which may confound the association between JD and health outcomes by explicitly accounting for the correlations between repeated measurements within each participant (27).

We also focused on the association between health outcomes in the concerned wave and JD experience before it; that is, we considered how health outcomes in wave t were associated with JD experience until wave t-1. This approach, which evaluates the presence of JD before health outcomes, is expected to mitigate simultaneity biases, which tend to overestimate the association between JD and health outcomes due to their reciprocal relationship (19, 20). Further, we examined the reverse causation from health outcomes to JD by estimating the association between health outcomes and JD one year later in the framework of mixed model analysis.

We considered three aspects of JD, evaluating it in terms of ability utilization (21, 22), workplace relationships (23, 24), and working conditions (25, 26), all of which are key determinants of JD, and combined them into a single-item measure. Regarding health outcomes, we focused on PD, poor SRH, and health-related resignation (HRR). PD measured by Kessler 6 (K6) scores (28, 29), represents mental health, SRH serves as a global measure of health status (30, 31), and HRR is a proxy for objective negative outcomes in the workplace. Given the observations in previous studies, we hypothesized that JD would be predictive of poor health outcomes in workers.

In summary, this study attempted to examine the association between JD and health outcomes and their reverse causation by applying mixed model analysis, which is expected to control for participant-specific factors that may confound the association between JD and health outcomes. The findings of this study are expected to provide new insights into the relevance of JD in occupational health to the existing literature, which consists mainly of cross-sectional or short-term prospective cohort studies.

Methods

Study sample

In this study, we used data obtained from a nationwide 14-wave panel survey, “The Longitudinal Survey of Middle-Aged and Older Adults,” conducted by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare (MHLW) each year from 2005 to 2018. Japan’s Statistics Law required the survey to be reviewed from statistical, legal, ethical, and other viewpoints. We obtained the survey data with the official permission of the MHLW; therefore, the current study did not require ethical approval.

The survey started with the cohort aged 50–59 years (born 1946–1955) in the first wave. A total of 34 240 individuals responded (response rate: 83.8%). The 2nd to 14th waves of the survey were conducted annually from 2006 to 2018; 20 677 individuals remained in the 14th wave. In wave t, we focused on the health outcomes of participants who reported their job satisfaction in wave t-1. Since the questions on JD were asked of employed workers, we removed participants who had not been employed (that is, who had been unemployed, self-employed, or other) before each concerned wave. After further excluding participants with missing key health variables (PD, SRH, and HRR) in each wave, we obtained 156 823 observations of 24 056 participants (13 177 men and 10 879 women), which were used for descriptive analysis.

For regression analysis, we further removed participants who were already psychologically distressed or whose health was assessed as poor or very poor (see below for definition) one year before each concerned wave because they may have been psychologically distressed or unhealthy due to reasons other than job dissatisfaction. Consequently, we used longitudinal data from 147 830 observations of 23 498 participants (12 901 men and 10 597 women) for the regression analysis.

Measures

Job dissatisfaction

The survey asked the participants to answer the question, “How do you feel about your job in terms of the following: (i) ability utilization, (ii) workplace relationships, and (iii) working conditions?” – all of which have been the key correlates of JD in preceding studies (21–26), on a five-point scale (1=satisfied, 2=somewhat satisfied, 3=average, 4=somewhat dissatisfied, and 5=dissatisfied). We calculated the sum of these scores (range: 3–15); Cronbach’s alpha varied 0.724–0.780 for each wave. We defined JD as a higher degree of overall dissatisfaction with the three job aspects; specifically, we defined it as a total score of ≥10, which accounted for 31.7% of the total respondents and roughly corresponded to the highest tertile of the total score. We then focused on how long the individuals had been continuously dissatisfied with their jobs before the concerned wave. We constructed four binary variables for JD duration: (i) ≥1 (ii) 1, (iii) 2, and (iv) ≥3 years, where (i) is a comprehensive definition of JD, including (ii)–(iv).

Health outcomes

We considered three health outcomes: PD, poor SRH, and HRR. We constructed K6 scores to measure the PD (28, 29). The reliability and validity of K6 has been demonstrated in a Japanese sample (32, 33). The participants were asked to answer a six-item questionnaire that included items such as “During the past 30 days, how often did you feel (a) nervous, (b) hopeless, (c) restless or fidgety, (d) so depressed that nothing could cheer you up, (e) that everything was an effort, or (f) worthless?” The questions were rated on a five-point scale (0=never to 4=all of the time). We then calculated the sum of the reported scores (range: 0–24) and defined it as the K6 score, whose Cronbach’s alpha varied 0.876–0.883 for each wave. Higher K6 scores reflect higher PD levels, and K6 scores ≥13 indicate serious mental illness in a Japanese sample, as validated by previous studies (29, 31). We constructed a binary variable for PD by assigning a value of 1 to those with K6 scores ≥13 and 0 to the others. We did not include data from respondents who did not report all six items.

Regarding SRH, the participants were asked to rate their current health condition as follows: 1 (very good), 2 (good), 3 (somewhat good), 4 (somewhat poor), 5 (poor), or 6 (very poor). SRH is correlated with morbidity and is predictive of changes in functional ability (31, 32). We constructed a binary variable for poor SRH by allocating 1 to those who chose 4–6 and 0 to the others.

We further constructed a binary variable for HRR by allocating 1 to those who answered that they stopped working for health reasons in the concerned wave and 0 to the others. This definition corresponded to a temporary leave from the workplace in most cases because the survey provided other reasons for leaving a job, such as being fired and mandatory retirement, and 95.3% of those who had resigned for health reasons resumed working in later years, allowing us to compare the results regarding sickness absence (11–13).

Covariates

We considered a set of participant-level covariates evaluated for each wave. Specifically, we constructed binary variables for gender (female=1; male=0) and marital status (having a spouse =1; otherwise=0). For age at baseline, we constructed binary variables for each age (for instance, 1=age 50 years, 0=otherwise). Occupational status was divided into six categories (managers, regular employees, non-regular employees [such as part-time, temporary, and contract worker], other, and unemployed) and constructed binary variables for each category (for instance, 1=managers, 0=otherwise). Similarly, we constructed binary variables for each category of educational qualification (junior high school, high school, junior college, college or above, other, and unanswered) and health behavior (currently smoking, heavy alcohol consumption, and no physical activity). We also considered household spending as a proxy for household income and adjusted it for household size by dividing it by the square root of the number of household members (34). We categorized them into quartiles and constructed binary variables for each quartile. For respondents who did not answer questions about household spending, we allocated a binary variable to unanswered questions. We also included binary variables for each wave to control for wave-specific effects. We did not use occupational status in wave t as a covariate when estimating HRR in wave t, because current occupational status (especially, no job and self-employed) may be a result of HRR in many cases.

Statistical analysis

For descriptive analysis, we compared the prevalence of each health outcome between those who were satisfied with their jobs and those who were not, and examined the extent to which the prevalence of each health outcome was correlated with JD duration.

For regression analysis, we estimated two logistic mixed models, Models 1 and 2, to predict the probability of each health outcome by JD, according to the choice of JD variables. For participant i in wave t, Model 1 is given by

where H is a binary variable for each health (PD, poor SRH, or HRR), JDT is a binary variable for JD duration of one year or longer, ɛ1 represents participant-specific factors, and u1 is an error term. Meanwhile, Model 2 is given by

where JD1, JD2, and JD3 are binary variables for JD duration of one, two, and three years or longer, respectively, ɛ2 represents participant-specific factors, and u2 is an error term.

In both models, we focused on the association between health outcomes in the concerned wave and JD experience to mitigate simultaneity bias. We also removed the respondents with PD or poor SRH in the previous year because they may have been psychologically distressed or unhealthy due to reasons other than JD. To check the robustness of the logistic mixed model results, we estimated the linear versions of Models 1 and 2 by replacing the binary health variable, H, with its continuous score.

Additionally, we estimated the logistic mixed model (Model 3) to predict JD in the concerned wave. Model 3 is given by

where JD is a binary variable for JD. PD, poor SRH, and JDT are binary variables for PD, poor SRH, and JD duration of one year or longer, respectively, all of which were evaluated in the year before each concerned wave. ɛ3 represents participant-specific factors, and u3 is an error term. This regression was aimed at examining the reverse causation from health to JD. To check the robustness of the estimation results, we estimated the logistic mixed model to predict JD using K6 and SRH scores instead of their binary variables. For all statistical analyses, we used the Stata software package (Release 15).

Results

Descriptive analysis

The proportion of participants who were dissatisfied with their jobs for ≥1 year before the concerned wave declined from 32.9% in the 2nd wave to 20.9% in the 14th wave. Table 1 summarizes the distribution of JD experience among the participants in the 7th wave, which was around the middle of the total number of waves, and compares the prevalence of each health outcome between those who were satisfied with their jobs and those who were dissatisfied with them. As seen in this table, 27.4% of men and 21.9% of women were dissatisfied with their job for ≥1 year before the 7th wave. The mean length of JD duration was 1.7 [standard deviation (SD) 1.1] years for men and 1.8 (SD 1.2) years for women. As expected, JD was associated with a higher prevalence of adverse health outcomes; for example, 3.8% of men who were dissatisfied with their jobs in the previous year experienced PD in the seventh wave, compared to 1.2% of men who were satisfied with their jobs. We also observed similar patterns in the other waves.

Table 1

Distribution of the study sample in terms of job dissatisfaction and health outcomes in the 7th wave.

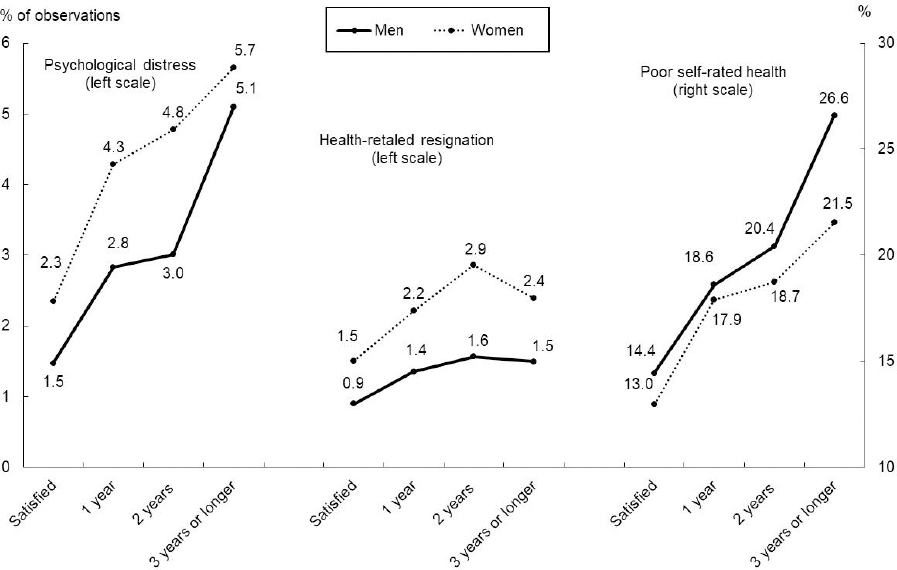

Based on pooled observations, figure 1 graphically illustrates a positive relationship between JD duration and the prevalence of each poor health outcome for both men and women. The slopes of the curves were not substantially different between genders for each health outcome, although the levels of the women’s curves were higher than those of men for PD and HRR and lower for poor SRH. These results suggest a limited interaction between JD and gender.

Figure 1

Prevalence of psychological distress by duration of job dissatisfaction. Note: a Indicated % prevelance of each health outcome among the observations with each duration of job dissastisfaction among the pooled observations (N=156 823 observations of 24 056 participants [13 177 men and 10 879 women.]

Regression analysis

Table 2 presents the results of Model 1 for each health outcome. The odds ratios (OR) of reporting PD, poor SRH, and HRR in response to JD for ≥1 year were 1.96 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.75–2.20], 1.33 (95% CI 1.26–1.40), and 1.57 (95% CI 1.40–1.73), all of which indicated a positive association between JD and poor health outcomes. We conducted a likelihood-ratio rate test to test the null hypothesis that there were no individual-level random effects. If this hypothesis is rejected, the mixed model must be applied; otherwise, we can use the pooled cross-sectional model. The test showed that the null hypothesis could be rejected (P<0.001) for all health outcomes, indicating that the mixed model was consistently preferred to the pooled cross-sectional model. In addition to these key results, the model showed that having no spouse, heavy alcohol consumption, and the lowest educational qualification (graduating from junior high school) were positively associated with poor health outcomes.

Table 2

Estimation results of logistic mixed models (Model 1 to predict health outcomes (N=147 830 observations of 23 498 participants. [OR=odds ratio; CI=confidence interval].

| Psychological distress | Poor self-rated health | Health-related resignation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| OR a | 95% CI | OR a | 95% CI | OR a | 95% CI | |

| Dissatisfied for ≥1 year | 1.96 | 1.75–2.20 | 1.33 | 1.26–1.40 | 1.57 | 1.40–1.75 |

| Female | 1.30 | 1.11–1.52 | 0.61 | 0.55–0.67 | 1.52 | 1.34–1.72 |

| Having no spouse | 1.96 | 1.75–2.20 | 1.33 | 1.26–1.40 | 1.57 | 1.40–1.75 |

| Health behavior | ||||||

| Smoking | 0.97 | 0.83–1.13 | 0.77 | 0.71–0.84 | 0.87 | 0.75–1.01 |

| Heavy alcohol consumption | 1.72 | 1.36–2.18 | 0.90 | 0.79–1.03 | 0.78 | 0.58–1.05 |

| No exercise | 1.91 | 1.70–2.15 | 1.51 | 1.43–1.62 | 0.78 | 0.69–0.87 |

| Occupational status | ||||||

| Manager | 0.73 | 0.54–0.97 | 0.89 | 0.78–1.02 | ||

| Non-regular employee | 0.94 | 0.80–1.09 | 0.95 | 0.89–1.03 | ||

| Self-employed | 1.14 | 0.89–1.45 | 0.91 | 0.80–1.03 | ||

| Other | 0.96 | 0.72–1.29 | 0.99 | 0.86–1.13 | ||

| No job | 2.20 | 1.82–2.66 | 1.81 | 1.65–1.99 | ||

| Household expenditure in quartiles (ref. = 4th quartile [highest] | ||||||

| 1st (lowest) | 0.98 | 0.83–1.16 | 0.83 | 0.77–0.91 | 1.71 | 1.45–2.02 |

| 2nd | 0.83 | 0.70–0.98 | 0.80 | 0.75–0.87 | 1.56 | 1.33–1.84 |

| 3rd | 0.94 | 0.81–1.09 | 0.90 | 0.84–0.97 | 1.28 | 1.08–1.50 |

| Unanswered | 1.01 | 0.80–1.28 | 0.94 | 0.84–1.05 | 1.10 | 0.86–1.40 |

| Educational attainment (ref. = college or higher) | ||||||

| Junior high school | 1.39 | 1.09–1.78 | 2.80 | 2.39–3.26 | 1.94 | 1.56–2.40 |

| High school | 1.06 | 0.87–1.29 | 1.76 | 1.56–1.99 | 1.56 | 1.30–1.87 |

| Junior college | 1.28 | 0.94–1.75 | 1.16 | 0.94–1.44 | 1.35 | 1.03–1.78 |

| Other or unanswered | 1.27 | 0.72–2.24 | 2.29 | 1.60–3.28 | 1.68 | 1.03–2.73 |

| Log likelihood | –9795.02 | –42472.06 | –8766.76 | |||

| Including the interaction between job dissatisfaction and women | ||||||

| Dissatisfied for ≥1 year | 2.06 | 1.76–2.41 | 1.31 | 1.22–1.41 | 1.42 | 1.21–1.67 |

| Female | 1.35 | 1.13–1.61 | 0.61 | 0.55–0.67 | 1.43 | 1.24–1.65 |

| Dissatisfied for ≥1 year × female | 0.90 | 0.71–1.13 | 1.03 | 0.92–1.15 | 1.21 | 0.96–1.51 |

| Log likelihood | –9794.56 | –42471.94 | –8765.41 | |||

The bottom of table 2 presents the key estimation results obtained after including the interaction term between JD and being female. The OR of the interaction term was not significantly different from that in all models, while the OR of the interaction term in logistic regression models could not be interpreted in a straightforward manner (35). Thus, we present the regression results for the entire sample, rather than separately for men and women in what follows.

Table 3 summarizes the key results of Models 1 and 2, adjusted for covariates, and compares the results between the logistic and linear models. These three findings are noteworthy. First, JD was positively associated with poor health outcomes in all model specifications. Second, a longer JD duration was associated with poorer health outcomes in most model specifications, a result consistent with the observations in table 1 and Figure 1. For instance, as JD duration increased from 1 to ≥3 years, the OR of reporting PD increased from 1.67 (95% CI 1.42–1.96) to 2.49 (95% CI 2.09–2.96) in the mixed model. Third, the results obtained using the linear models were consistent with those obtained from the logistic results.

Table 3

Estimation results of mixed models (Models 1 and 2) to predict health outcomes (N = 147 830 observations of 23 498 participants). [OR=odds ratio; CI=confidence interval]

| Psychological distress | Poor self-rated health | Health-related resignation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| OR a | 95% CI | OR a | 95% CI | OR a | 95% CI | |

| Logistic mixed models | ||||||

| Model 1 | 1.96 | 1.75–2.20 | 1.33 | 1.26–1.40 | 1.57 | 1.40–1.75 |

| ≥1 year | ||||||

| Model 2 (years) | ||||||

| 1 | 1.67 | 1.42–1.96 | 1.19 | 1.10–1.28 | 1.34 | 1.14–1.57 |

| 2 | 1.76 | 1.40–2.22 | 1.30 | 1.17–1.45 | 1.71 | 1.38–2.13 |

| ≥3 | 2.49 | 2.09–2.96 | 1.61 | 1.46–1.77 | 1.61 | 1.35–2.91 |

|

|

|

|

||||

| K6 score b(range: 0–24) | Self-rated health score c(range: 1–6) | Health-related resignation (range: 0–1) | ||||

|

|

|

|

||||

| Coefficent | 95% CI | Coefficent | 95% CI | Coefficent | 95% CI | |

|

|

|

|

||||

| Linear mixed models | ||||||

| Model 1 | ||||||

| ≥1 | 0.27 | 0.24–0.31 | 0.05 | 0.04–0.06 | 0.006 | 0.004–0.007 |

| Model 2 (years) | ||||||

| 1 | 0.16 | 0.12–0.21 | 0.03 | 0.02–0.04 | 0.004 | 0.002–0.006 |

| 2 | 0.27 | 0.21–0.34 | 0.05 | 0.04–0.07 | 0.007 | 0.004–0.011 |

| ≥3 | 0.45 | 0.39–0.52 | 0.10 | 0.08–0.11 | 0.006 | 0.004–0.008 |

Table 4 presents the results of Model 3, which explains a binary variable for JD in the concerned wave by one-year lagged variables for PD, poor SRH, and JD. The table showed that JD was positively associated with both PD and poor SRH in the previous year with an OR of 1.50 (95% CI 1.35–1.67) and 1.37 (95% CI 1.30–1.43), respectively. The bottom panel of the table confirms that replacing binary variables for health with the continuous variables obtained results that were consistent with those in the binary model.

Table 4

Estimation results of logistic regression models (Model 3) to predict job dissatisfaction (N=136 998 observations of 22 058 participants). [OR=odds ratio; CI=confidence interval].

| OR a | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

| Using binary variables of health | ||

| Psychological distress (lagged) | 1.50 | 1.35–1.67 |

| Poor self-rated health (lagged) | 1.37 | 1.30–1.43 |

| Job dissatisfaction (lagged) | 3.28 | 3.16–3.41 |

| Using continuous variables of health | ||

| K6 score b(lagged, range: 0–24) | 1.18 | 1.16–1.20 |

| Self-rated health score c (lagged; range: 1–6) | 1.13 | 1.11–1.15 |

| Job dissatisfaction (lagged) | 3.23 | 3.11–3.36 |

a Odds ratio for reporting job dissatisfaction (for K6 and self-rated health scores, in response to their 1-standard deviation increases). Adjusted for covariates (gender, marital status, health behavior, occupational status, household expenditure, educational attainment, age at baseline, and waves).

Discussion

In this study, we examined the association between JD and health outcomes among middle-aged workers, controlling for individual attributes. To take full advantage of repeated measures for each participant over time, we conducted a mixed model analysis of the 14-wave longitudinal data of middle-aged workers. As hypothesized, the results indicated that JD is a key predictor of adverse health outcomes in workers.

These results were generally consistent with those obtained in previous studies (3–13), most of which were based on cross-sectional or prospective cohort studies. In addition, the observed impact on HRR was in line with that reported in previous studies on the impact of JD on negative outcomes in the workplace (11–16). We confirmed the validity of the conventional view that JD is an important determinant of occupational health, even when controlling for participant-specific attributes.

Second, we observed that a longer JD duration moderately added to the risks of each poor health outcome, as shown in both the descriptive and mixed model analyses. While studies have shown that JD tended to discourage workers from staying in the workplace (11–16), the results suggest that a prolonged JD duration was associated with an average deterioration in health outcomes.

Third, behind this accumulating effect of JD duration, there may be cumulative causation between JD and health outcomes. As seen in table 4, JD was not only affected by JD duration until the previous year but also by the previous year’s PD and poor SRH, which had been affected by JD duration beforehand, as suggested by the results in table 3. The existence of the latter route suggests that PD and poor SRH may mediate the impact of previous PD experience on current PD. This mediation mechanism is likely to enhance JD’s self-sustainability and thus make JD adversely affect health over time.

This study focused on middle-aged workers, who were more exposed to the onset of health problems compared to other age groups (36, 37). Hence, the observations in this study may help assess the potential magnitude of the association between JD and health in all age groups. However, many studies have shown that age can be a moderator in the association between work characteristics and occupational well-being indicators (38); for instance, JD is known to be more sensitive to job instability among younger than older workers (39). Hence, it is reasonable to suspect that the association between JD and health outcomes may differ across age groups, suggesting the need to expand the analysis to cover workers of all ages.

This study has several limitations. First, we ignored the possibility that JD may have various aspects and that each may affect health outcomes independently and differently because we combined three aspects of JD – dissatisfaction with ability utilization, workplace relationships, and working conditions – into a single-item measure. Previous observations that job dissatisfaction is substantially affected by psychosocial work factors, such as support from superiors and colleagues (40, 41), suggest a closer association of dissatisfaction with workplace relationships. Therefore, the relative effect of each JD aspect on PD and their relationships should be examined in future research.

Second, the association between job satisfaction and health outcomes is likely to be confounded by job status, especially in full-time and part-time jobs. Low job satisfaction and poor health status are more common among part-time than full-time workers (42), and the confounding effects of job status may be affected by socio-institutional factors related to equal treatment between full- and part-time workers. The analysis of these effects remains a topic for future research.

Third, this study ignored potential biases due to attrition. The proportion of participants who were dissatisfied with their job declined over the waves, suggesting the possibility that the observed association between JD and health outcomes may have been underestimated. Mixed models in this study focused on the short-term association between JD and health, but the analysis of the long-term impact of JD on health should control for potential attrition biases considering the possibility that unhealthy participants were more likely to have dropped out of the survey.

Concluding remarks

Despite these limitations, we can conclude that JD is modestly associated with poor health among middle-aged workers. Policymakers and managers should regularly monitor employees’ job dissatisfaction and make efforts to improve their work environments to enhance their occupational health.