Young adults living with episodic disabilities can experience

unpredictable disruptions to their employment as they enter and advance

within the labor market. The most prevalent physical (e.g., juvenile

arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease) and mental health (e.g., anxiety,

depression) chronic conditions are often categorized as episodic, with

periods of good health interrupted by flares of poor health (1). Some estimates suggest one out of six

of working-aged adults with disabilities report fluctuating and

unpredictable limitations (2).

The unpredictability of an episodic disability can be stressful and

impact the health and quality of life of young adults. Finding and

sustaining employment can also be challenging, especially managing

fluctuations in symptoms while also navigating the changing demands of

work (3–5). Many episodic conditions have few visible signs

creating challenges communicating about work support needs (6, 7). Living and working with an episodic disability may

have different impacts at various life stages; difficulties at the early

career phase can have an economic scarring effect that impact both

employment opportunities and health across the life course (8, 9).

To manage their health and well-being, many young adults with episodic

disabilities rely on employment not only for income but also for resources

(e.g., extended health benefits, drug coverage) that may improve or

sustain good health (9). To examine

this further, our study reviewed employment and income support

interventions and their impact on the health and well-being of young

adults living with episodic disabilities.

Methods

A systematic review addressed the study aim (10). To inform the search strategy and synthesize key

findings, consultations with knowledge users were held. The review was

registered with PROSPERO (CRD42021268354) and met 2020 PRISMA

Guidelines.

Literature search

The search strategy captured employment or income support

intervention studies for young adults [i.e., sample mean age 16–35

(range 16–45) years] living with any episodic disability (Table 1). Our search was restricted

to intervention studies conducted in OECD countries, those that used

quantitative methodologies, and were published in the last 20 years in

English, French or Spanish. We examined the effect of employment or

income support inteventions on any health outcome. Medline, Embase,

PsycINFO, CINAHL, Sociological Abstracts, ASSIA, ABI Inform, and Econ

lit were searched using database-specific controlled vocabulary terms

and keywords (Supplementary material, www.sjweh.fi/article/4133,

Table S1).

Table 1

Inclusion and exclusion criteria using PICO

framework

|

PICO category |

Inclusion criteria |

Exclusion criteria |

|

Population |

Young adults (sample mean age 16-35 years and age

range 16 and 45 years)

Living with any episodic health

condition

Study sample located in an OECD labor market

country |

Study sample not classified as a young adult or

with an episodic disability

Study sample located in a

non-OECD context |

|

Intervention |

Any intervention that targeted

employment or income support |

Intervention with no employment

or income support component |

|

Comparison |

Any comparator group (population

not taking part or exposed to the intervention) |

No comparison group |

|

Outcome |

Any physical or mental health outcome, measure of

health-related quality of life or assessment of

well-being |

Studies evaluating the effectiveness of an

intervention which did not assess outcomes of interest |

Relevance screening

Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts and

full-texts for relevancy using DistillerSR (11). Disagreements were discussed in meetings.

Reference lists of included articles were checked to identify

additional relevant articles.

Quality appraisal and data extraction

A quality appraisal tool for studies in work and health was used to

assess the internal, external, and statistical validity of eligible

articles (10). The tool

assessed risk of bias in study design and objectives, recruitment

procedures, outcome and exposure measurement and analysis

(Supplementary Table S2). Two reviewers appraised each relevant

article. A final weighted sum score of the quality criteria was

generated, converted to a percentage score, and categorized as high

(≥85% of quality appraisal score), medium (50–84% of total quality

appraisal score) or low quality (<50% of quality appraisal total

score). Consensus on scores was reached in a team meeting.

Evidence synthesis

The limited number of eligible studies identified by the review

coupled with variability in the observation length, intervention type,

sample characteristics, outcomes meant that we were unable to

calculate pooled effect estimates. Instead, a narrative synthesis

described the findings.

Results

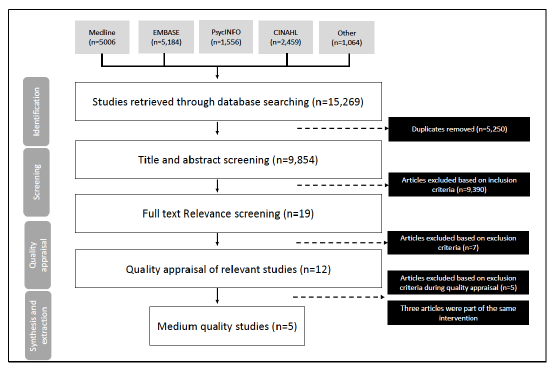

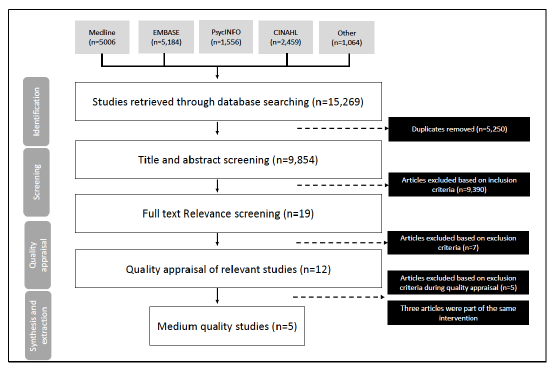

Our search yielded 15,269 articles published between years 2001–2021.

Only five eligible employment interventions focused on young adults with

an episodic disability and assessed health impacts (Figure 1). All

articles were appraised as medium quality. A summary of each study is

provided in Table 2.

Table 2

Description of studies identified in systematic review

examining income and employment interventions on health

Author,

Year,

Country |

Study objectives |

Study design, length of data collection, and

setting |

Sample size description |

Episodic disability group |

Employment and income outcomes (measures

utilized) |

Health and well-being outcomes (measures

utilized) |

Geenen

et al,

2015,

USA |

To examine whether youth who participated in the

Better Future’s project showed improved outcomes when compared

to youth randomized to a control group who were offered standard

services. |

Randomized

controlled trial

16

months

Community setting |

N=67 (36

intervention; 31

control)

Mean age 16.8 ± 0.62 years

52.2%

female |

Youth with mental health challenges in foster

care |

Employment status

Career decision

self-efficacy |

Improvements in mental health (Youth

Efficacy/Empowerment Scale- Mental Health)

Mental health

recovery (Mental Health Recovery Measure)

Hopelessness

(modified Hopelessness Scale for Children)

Quality of

life (Quality of Life Questionnaire) |

Liljeholm et al,

2020,

Sweden |

To determine how the Södertälje

Supported Employment and Education model, an integrated mental

health and vocational support intervention, can impact mental

health among young adults with mood disorders. |

Prospective Longitudinal pre-post

intervention study

12 months

Community

setting |

N=42

Mean age 21 (range

18–28)

years

64.3% female |

Young adults with major depressive

(93%) or bipolar disorder (7%) |

Engagement in everyday life

(Profiles of Occupational Engagement in people with Severe

mental illness [POES]) |

Mental health symptomology and

recovery (Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating

Scale)

Quality of life (Manchester Short Assessment of

Quality of Life [MANSA]) |

Menrath

et al,

2019

Germany |

To study the efficacy and impact

of the Modular Transition (ModuS-T) patient education program,

designed to support young adults living with chronic conditions

manage their disease and transition to adulthood, when compared

to young adults in usual care. |

Quasi-randomized control

study

4 weeks

Clinical setting |

N=300

Mean age 17.6 ± 1.6

years

47% female |

Young people with chronic

conditions: asthma (5.3%), attention deficit disorder

/hyperactivity disorder (18.7%), type 1 diabetes (19.7%),

phenylketonuria (2.3%), inflammatory bowel disease (16.0%),

cystic fibrosis (2.7%), chronic kidney disease (4.0%), epilepsy

(7.7%), organ transplantation (7.3%), juvenile idiopathic

arthritis (7.7%), esophagus atresia (12.0%), Ehlers-Danlos

syndrome (2.7%) |

Work preparedness (Transition

Competency Scale) |

Health-related quality of life

(DISABKIDS Chronic Generic Measure; SF-8)

Self-reported

health

Engagement in health care (German Patient

Activation Measure for Adolescents)

Health

condition-related knowledge (Transition Competence

Scale)

Health care competence (Transition Competence

Scale) |

Kane et al,

2016

USA

Rosenheck et al,

2017

USA

Rosenheck et al, 2017

USA |

To compare the NAVIGATE

coordinated specialty care program on receipt of disability

income support benefits, employment, treatment and first-episode

psychosis outcomes when compared to usual community care. |

Clustered randomized

trial

24 months

Clinical setting |

N=404 (223 intervention; 181

community care)

Mean age: (intervention) 23.18 ± 5.21

years; (community care) 23.08 ± 4.90 years

27%

female |

Individuals with first episode of

psychosis |

Work participation

Number

of days participating in work

Receipt of disability

income support |

Schizophrenia symptom severity

(Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale)

Depression

symptoms (Calgary Depression Scale for

Schizophrenia)

Mental health illness severity (Clinical

Global Impressions Severity Scale)

Quality of life

(Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale) |

Sveindottir et al,

2020

Norway |

To study the role of the Individual placement and

support (IPS) approach for young adults with mental and

behavioural conditions, at risk of early work disability when

compared to traditional vocational rehabilitation. |

Two-armed randomized control trial

12

months

Community setting |

N=96 (50 intervention group; 46 control

group)

Mean age: (intervention) 23.96 ± 3.46 years

(control) 23.85 ± 3.04

32% female |

Individuals with mental and behavioral

conditions |

Paid competitive employment

Proportion of

participants working ≥20 hours per week

Total number of

hours worked |

Disability (World Health Organization Disability

Assessment Schedule [WHODAS] 2.0)

Psychological distress

(Hopkins Symptom Checklist)

Severity of subjective health

complaints (Subjective Complaints Inventory)

Fatigue

(Chalder Fatigue Questionnaire)

Coping, helplessness, and

hopelessness (Theoretically Originated Measure of the Cognitive

Activation Theory of Stress [TOMCATS])

Alcohol

consumption (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test

consumption questions [AUDIT-C])

Drug use (Drug Use

Disorders Identification consumption questions

[DUDIT-C])

Global well-being (Cantril Ladder Scale) |

Figure 1

Systematic review flowchart.

The five employment interventions found improvements in health

outcomes (Table 3). A randomized

controlled trial (RCT) of a personalized coaching initiative in the

United States offered mentorship to young adults with mental health

conditions to meet career and educational goals and build career

self-determination. Although the intervention did not contribute to a

change in employment over the six months following the ten-month

intervention period, it was associated with improved career

self-efficacy. Intervention recipients reported greater mental health

but no difference in quality of life when compared to the control group

(12).

Table 3

Description of study interventions and their impact on income

and employment outcomes and health outcomes

|

Study |

Description of intervention |

Intervention’s impact on income and employment

outcomes |

Intervention’s impact on health and well-being

outcomes |

Quality appraisal |

Geenen

et al, 2015 |

The Better Futures project is a personalized

coaching intervention program that provides foster youth with

mental health challenges to identify and work on their personal,

education or career goals, build self-determination skills

through mentorship workshops with advisory peers who have had

similar experience in foster care and dealing with their mental

health challenges. |

No significant difference in the proportion of

participants who were employed at follow-up when comparing the

intervention group to the control group.

Over the study

period, the intervention group reported significantly greater

career decision self-efficacy when compared to the control group

F (3, 124)=6.06; P=0.0007. |

Over the study period, the intervention group

reported significantly greater efficacy in mental health care

management when compared to the control group F(3, 118)=9.07;

P<0.0001).

While the intervention group reported

greater mental health recovery over the study period when

compared to the control group, the difference was

non-significant F (3, 180)=2.55, P=0.06).

There was no

difference between intervention and control groups in quality of

life over the study period F (3, 118)=2.29,

P=0.82).

There was a significant decline in hopelessness

among the intervention group, when compared to the control group

over the study period F (3, 62)=2.79, P=0.048). |

Moderate |

Lijeholm

et

al, 2020 |

The Södertälje Supported

Employment and Education model is an integrated intervention

targeted towards young adults with major depressive or bipolar

disorders to improve their mental health and support employment.

Intervention included integrated vocational services with mental

health services, personalized benefit counselling and employer

relationship building. All services were delivered by a case

manager and aligned with the client’s preferences and

needs. |

Participants reported

statistically significant improvements to engagement in everyday

life activities at 12-months when compared to baseline

(P=0.002). |

Although depression symptomology

decreased at follow-up when compared to baseline, the

relationship was not statistically significant

(P=0.241).

Participants indicated greater quality of life

at follow-up when compared to baseline (P=0.007).

At 12

months, participants who reported engagement in everyday life

activities were significantly less likely to report depression

severity (r=-0.313, P<0.05) and reported higher quality of

life (r=0.470, P<0.05). |

Moderate |

Menrath

et al,

2019 |

The Modular transition (ModuS-T)

education program aims at empowering patients with chronic

conditions to take responsibility in managing their disease.

Modules on insurance, the health care system, career, social

networking, coping and stress management, health promotion

behaviours, were delivered participants and their

parents/caregivers. Group discussions, role playing, and case

studies were utilized to deliver the training. |

Young adults in the intervention

group observed significantly greater scores for work

preparedness (TC-a) over the duration of the study when compared

to those in the control group F=27.3 (p < 0.001). |

No significant difference existed

when comparing the intervention group to the control group on

health-related quality of life when using the

DISABKIDS.

Young adults in the intervention group showed

significantly higher engagement in health care when compared to

the control group over the study period F=8.1,

P<0.001).

Young adults in the intervention group

showed significantly higher health condition-related knowledge

when compared to the control group over the study period F=22.9,

P<0.001).

Young adults in the intervention group

showed significantly higher health care competence when compared

to the control group over the study period (F=56.9,

P<0.001). |

Moderate |

Kane et al,

2016

Rosenheck et al, 2017

Rosenheck et al,

2017 |

NAVIGATE intervention is a

four-component training approach that includes: 1) customized

medication management training; 2) family psychoeducation 3)

self-management training focused on building resilience and 4)

supported employment and education. |

Compared to community care,

intervention participants were significantly more likely to

report work participation. However, the main effect by time was

most significant for those who participated in >3 supported

employment/education sessions (t=0.16, P<0.05).

No

significant differences between intervention and community care

when comparing number of days

in work (t=0.097,

P=0.16).

No significant differences between intervention

and community care when comparing receipt of disability income

support (t=4.25, P=0.71). |

Intervention participants

experienced significantly greater improvement in quality of life

over the study period than those in community care (t=2.45,

P=0.015).

Intervention participants reported a

significant decrease in schizophrenia symptom severity when

compared to those in community care (t=-2.41,

P=0.02).

Intervention participants indicated a

significant decrease in depressive symptoms when compared to

those in community care (t=-2.15, P=0.032).

No

significant difference in mental health illness severity between

intervention participants when compared to those in community

care over the study period (t=-1.52, P=0.13). |

Moderate |

|

Sveindottir et al, 2020 |

The individual placement and support (IPS) model of

supported employment is an intervention approach that is

targeted towards enhancing competitive employment outcomes for

patients with severe mental health illness through focusing on

patient goals and preferences, providing long-term personalized

support, access to integrated services and counselling. The

intervention was facilitated by a job specialist who matched the

candidate with a job and provided ongoing support following a

job through established IPS principles. |

IPS participants were significantly more likely to

hold competitive employment at 12-month follow-up compared to

the traditional vocational rehabilitation group (OR=10.39, 95%

CI 2.79-38.68).

A significantly higher proportion of IPS

participants reported working ≥20 hours per week at the 12-month

follow-up compared to the traditional vocational rehabilitation

group (OR=8.75, 95% CI 1.83-41.75).

A significantly

higher proportion of IPS participants reported working more

hours at the 12-month follow-up compared to the traditional

vocational rehabilitation group (Cohen’s D=0.70, p=0.002). |

Participants in the intervention group reported

significantly less health complaints (P=0.017), helplessness

(P=0.017) and hopelessness (P=0.006), and drug use (P=0.036)

when compared to the traditional vocational rehabilitation group

at 12-months.

Participants in the intervention group

reported significantly less disability (P=0.038) and greater

perception of future well-being (P=0.038) when compared to the

traditional vocational rehabilitation group at 12-months. |

Moderate |

Three supported employment interventions in community and clinical

settings for young adults with mental health conditions were identified

(13–15). The interventions provided employment placement

services, career counselling and health-related self-management

assistance. Findings highlighted improved occupational engagement,

participation in employment, and hours worked (13–15), as well

as improvements in quality of life and well-being, declines in

depressive symptom severity, fewer health complaints, and less

disability. Supported employment embedded within a specialty health care

program for individuals with psychosis and their families showed a

dose–response relationship such that attending a greater number of

sessions increased the likelihood of participating in employment (16). Intervention participants also

reported greater quality of life and a decrease in mental health

symptoms when compared to the control group.

Finally, a German patient education program within a clinical setting

for young adults with diverse chronic health care conditions (a majority

were episodic) included a specific career development module (17). Intervention participants were

more likely to report greater work-preparedness as well as better

health-related quality of life when compared to the control group.

Discussion

The unpredictable and dynamic nature of an episodic disability in

young adulthood can contribute to early and sustained exclusion from the

labor market and intermittently disrupt the pathway between employment

and health. Past research has highlighted the health-related benefits

attributed to promoting employment (18). This systematic review examined whether employment

or income support interventions could benefit the health and well-being

of young adults with episodic disabilities.

We found an absence of high-quality evidence-based employment or

income support interventions for young adults living with episodic

disability that focuses on health-related impacts. Only five studies

were identified which met our eligibility criteria, despite a large body

of research highlighting the importance of employment as a critical

social determinant of health in young adults with and without

disabilities (19, 20). Results underscore the need to

elaborate on the health and well-being implications of employment

interventions for young adults with different episodic health

conditions. Most interventions identified in our review focused on young

adults with mental health conditions. Findings could reflect a growing

acknowledgment of the relationship between poor mental health and

difficulties participating in employment among young adults (21, 22). Episodic disabilities like juvenile arthritis or

inflammatory bowel disease are among the most prevalent among young

adults and are characterized by variable physical symptoms (e.g., pain,

fatigue, and activity limitations) and can considerably impact

employment (3). Moving forward,

tailored interventions should be designed to account for the employment

challenges of young people living with diverse episodic health

conditions.

Although we uncovered a small body of evidence, our review suggests

that involvement in employment interventions could provide benefits for

the health of young adults with episodic disabilities, all interventions

included employment and disability-specific support components which may

have explained the health-related benefits. Interventions that promote

employment for young adults with episodic disabilities may benefit from

providing specific training on balancing health and work demands.

Additional longer-term research is needed to better understand the

elements of employment interventions that may be valuable to health, as

well as the reciprocal relationship between work and health outcomes

that can emerge over time. Participation in supported employment offers

a promising practice which may foster employment engagement and improve

health. Supported employment interventions aid with finding work and

they offer regular counselling and job-related training which has been

previously shown to be beneficial for the employment of young adults

with disabilities (23). As our

findings suggest, the benefits of supported employment interventions

could extend to health and well-being of young adults with episodic

disabilities at the early career phase.

The fluctuating nature of episodic disabilities represents a unique

challenge to sustaining employment (6). Interventions in our systematic review did not

explicitly address the varying activity limitations and employment

restrictions that can emerge. There is a need to study the unpredictable

employment challenges related to an episodic disability and develop

relevant programing tailored to those at the early career phase.

Additionally, most interventions focused on helping participants find

employment. There was limited focus on employment conditions, including

managing jobs of different quality, access to support and job

accommodations, and health and safety which may shape health outcomes.

For instance, young adults with an episodic health condition may

experience challenges finding full-time permanent employment that offers

income and resources that are beneficial to health (16). There is a need to expand

employment interventions to ensure young adults living with episodic

disabilities can navigate aspects of the work environment which could

pose challenges to sustained employment and also adversely impact

health.

A study strength includes a rigorous systematic review methodology. A

limitation of our systematic review is that we did not include

qualitative studies or grey literature. Capturing broader forms of

evidence can be used to elaborate on the different employment

intervention that can promote health.

Concluding remarks

Our systematic review highlights the need to elaborate on the

impact employment programs can have on the health and well-being of

young adults living with diverse episodic disabilities. Additional

insights are needed to understand how interventions can be designed to

tailor and expand employment services to young adults living with

episodic health conditions to fully optimize the pathways to better

health.

Funding statement

Dr. Jetha’s salary is partially supported by a Stars Career

Development Award (20-0000000014) from the Arthritis Society (Canada).

The funding body had no role in study design, data collection, data

interpretation or manuscript writing. Several members of the authorship

team are employees of the Institute for Work & Health, which is

supported through funding from the Ontario Ministry of Labour,

Immigration, Training and Skills Development (MLITSD). The analyses,

conclusions, opinions, and statements expressed herein are solely those

of the authors and do not reflect those of the MLITSD; no endorsement is

intended or should be inferred.

Competing interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval

No ethics approval is required for the systematic review process.

References

Accommodating and Communicating

about Episodic Disabilities (ACED), Institute for Work & Health

(IWH). Project overview: what are episodic disabilities? [online].

2023 Available from: https://aced.iwh.on.ca/project-overview

Morris S, Fawcett G, Timoney

LR, Hughes J. The dynamics of disability: progressive, recurrent or

fluctuating limitations. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada;

2019.

Jetha

A,

Gignac

MA,

Bowring

J,

Tucker

S,

Connelly

CE,

Proulx

Let

al. Supporting arthritis and

employment across the life course: a qualitative

study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken)

2018

Oct;70(10):1461–8.

[CrossRef]

[PubMed]

Gmitroski

T,

Bradley

C,

Heinemann

L,

Liu

G,

Blanchard

P,

Beck

Cet

al. Barriers and facilitators to

employment for young adults with mental illness: a scoping

review. BMJ Open 2018

Dec;8(12):e024487.

[CrossRef]

[PubMed]

O’Brien

KK,

Davis

AM,

Strike

C,

Young

NL,

Bayoumi

AM.

Putting episodic disability into context: a qualitative

study exploring factors that influence disability experienced by

adults living with HIV/AIDS. J Int AIDS

Soc 2009

Nov;12(1):5. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

Gignac

MA,

Jetha

A,

Ginis

KA,

Ibrahim

S.

Does it matter what your reasons are when deciding to

disclose (or not disclose) a disability at work? The association of

workers’ approach and avoidance goals with perceived positive and

negative workplace outcomes. J Occup

Rehabil 2021

Sep;31(3):638–51.

[CrossRef]

[PubMed]

Jetha

A,

Tucker

L,

Backman

C,

Kristman

VL,

Bowring

J,

Hazel

EMet

al. Rheumatic disease disclosure

at the early career phase and its impact on the relationship between

workplace supports and presenteeism. Arthritis

Care Res (Hoboken) 2022

Oct;74(10):1751–60.

[CrossRef]

[PubMed]

Jetha A, Gignac M. Changing

Experiences, Needs, and Supports Across the Life Course for Workers

Living with Disabilities. Handbook of Life Course Occupational Health

Handbook Series in Occupational Health Sciences. New York, N.Y.:

Springer; 2023. p. 1–22.

Strandh

M,

Winefield

A,

Nilsson

K,

Hammarström

A.

Unemployment and mental health scarring during the life

course. Eur J Public Health

2014

Jun;24(3):440–5.

[CrossRef]

[PubMed]

Geenen

S,

Powers

LE,

Phillips

LA,

Nelson

M,

McKenna

J,

Winges-Yanez

Net

al. Better futures: a randomized

field test of a model for supporting young people in foster care with

mental health challenges to participate in higher

education. J Behav Health Serv Res

2015

Apr;42(2):150–71.

[CrossRef]

[PubMed]

Liljeholm

U,

Argentzell

E,

Bejerholm

U.

An integrated mental health and vocational

intervention: A longitudinal study on mental health changes among

young adults. Nurs Open

2020

Jul;7(6):1755–65.

[CrossRef]

[PubMed]

Sveinsdottir

V,

Lie

SA,

Bond

GR,

Eriksen

HR,

Tveito

TH,

Grasdal

ALet

al. Individual placement and

support for young adults at risk of early work disability (the SEED

trial). A randomized controlled trial. Scand J

Work Environ Health 2020

Jan;46(1):50–9.

[CrossRef]

[PubMed]

Kane

JM,

Robinson

DG,

Schooler

NR,

Mueser

KT,

Penn

DL,

Rosenheck

RAet

al. Comprehensive versus usual

community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the

NIMH RAISE early treatment program. Am J

Psychiatry 2016

Apr;173(4):362–72.

[CrossRef]

[PubMed]

Shahidi

FV,

Jetha

A,

Kristman

V,

Smith

PM,

Gignac

MA.

The Employment Quality of Persons with Disabilities:

Findings from a National Survey. J Occup

Rehabil 2023

Dec;33(4):785–95.

[CrossRef]

[PubMed]

Menrath

I,

Ernst

G,

Szczepanski

R,

Lange

K,

Bomba

F,

Staab

Det

al. Effectiveness of a generic

transition-oriented patient education program in a multicenter,

prospective and controlled study. J Transit

Med

2018;1(1):20180001.

[CrossRef]

Moore

TH,

Kapur

N,

Hawton

K,

Richards

A,

Metcalfe

C,

Gunnell

D.

Interventions to reduce the impact of unemployment and

economic hardship on mental health in the general population: a

systematic review. Psychol Med

2017

Apr;47(6):1062–84.

[CrossRef]

[PubMed]

Norström

F,

Virtanen

P,

Hammarström

A,

Gustafsson

PE,

Janlert

U.

How does unemployment affect self-assessed health? A

systematic review focusing on subgroup effects.

BMC Public Health 2014

Dec;14(1):1310. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

Vancea

M,

Utzet

M.

How unemployment and precarious employment affect the

health of young people: A scoping study on social

determinants. Scand J Public Health

2017

Feb;45(1):73–84.

[CrossRef]

[PubMed]

Bartelink

VH, Zay

Ya K,

Guldbrandsson

K,

Bremberg

S.

Unemployment among young people and mental health: A

systematic review. Scand J Public

Health 2020

Jul;48(5):544–58.

[CrossRef]

[PubMed]

Fiori

F,

Rinesi

F,

Spizzichino

D, Di

Giorgio

G.

Employment insecurity and mental health during the

economic recession: an analysis of the young adult labour force in

Italy. Soc Sci Med 2016

Mar;153:90–8. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

Jetha

A,

Shaw

R,

Sinden

AR,

Mahood

Q,

Gignac

MA,

McColl

MAet

al. Work-focused interventions

that promote the labour market transition of young adults with chronic

disabling health conditions: a systematic review.

Occup Environ Med 2019

Mar;76(3):189–98.

[CrossRef]

[PubMed]