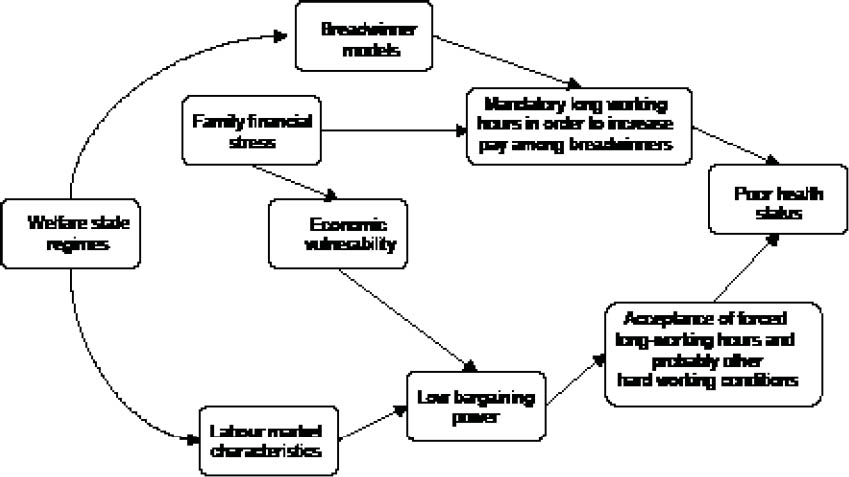

Although in recent years interest in health problems related to long working hours has increased, studies concerning the different areas of health are still scarce and have been focused on very long working hours, which are uncommon in Europe. The detrimental impact of extreme overtime work has often been demonstrated, but the unfavorable impact of moderately long working hours on health and well-being has not been consistently shown (1–6). Moderately long working hours and their impact on health have been related to family financial stress and the breadwinner role: in situations of family financial stress, breadwinners are likely to be forced to work long hours in order to increase the family income (7, 8). Therefore, apart from methodological reasons, the contradictory results of previous studies could be explained by different breadwinner models across countries.

Some studies have highlighted the crucial role of choice in determining a person’s response, in terms of health and well-being, to working long hours (7–13). Two theoretical approaches have been proposed to account for the obligation to work long hours: consumerism and bargaining power (14). Consumerism may lead families to desire and expect high levels of consumer spending that traps some family members in situations requiring them to work long hours (8, 15). The importance of family financial stress, not only related to consumerism but also to other aspects such as low wages, has been identified as a reason for being forced to work long hours that can lead to poor health outcomes (7, 8). A review about long working hours in the UK reported that those who worked longer hours were more likely to (i) be men with children, (ii) have large mortgages or a high cost of living, and (iii) have a partner who either does not work at all or does not work full time (16). Bargaining power considerations suggest that where employers hold greater leverage over employees, as in the case of non-unionized workplaces, workers who receive low pay, have temporary contracts, or are in situations of economic vulnerability, are more likely to be forced to work long hours. Many workers, primarily breadwinners, are obliged to accept high work demands simply to service their family debt (17–20).

Since breadwinner models and labor market characteristics related to bargaining power differ across European countries, the patterns of associations between long working hours and health status may also differ. It has been pointed out that Esping-Andersen’s (21) welfare regime approach contains important starting points for the explanation of the differences in family models of welfare states (22, 23). For this analysis, a family arrangements approach that deconstructs the breadwinner and caregiver family roles for both sexes has been proposed (24). The respective family arrangements, and the history of these, overlap in specific ways with the welfare state regime (22, 25). This framework fits with an approach of analysis of the long working hours and health status relationship based on the breadwinner role.

In Europe, liberal countries such as the UK and, to a lesser extent, Ireland, combine a deregulated labor market with a strong male breadwinner model, with the husband seen as being primarily responsible for work and the wife as responsible for running the private household (26). Although in the UK most married people are dual-earning couples, women’s wages are far below breadwinner levels (27). Corporative welfare regimes, such as Germany or France, and Southern European countries, have a “male breadwinner/caregiver part-time” model based on the acceptance of the limited integration of women into the labor market without involving the abandonment of males’ responsibility for many of the care activities. The “dual breadwinner/external care” model is a form especially promoted by Nordic countries that involves the participation of parents in the labor market, made possible by a major outsourcing of care services by the welfare state. Eastern European countries also have dual breadwinner models with high labor market participation of women and low gender-related pay gaps. However, within the family, traditional ways of constructing men and women’s roles remain. Moreover, the economic damage to state revenues has undermined the social policies that supported them as workers and mothers (28, 29).

European countries also differ in their workers’ bargaining power. Although collective bargaining in the EU states covers 66% of workers, there are great variations among countries, the lowest levels of coverage, around 30%, being found in the UK and most Eastern European countries (30). Figure 1 summarizes the conceptual model for understanding between-country differences in the relationship between long working hours and health status proposed in this study.

Figure 1

Proposed conceptual model for explaining between-country differences in the relationship between long working hours and health status.

The objectives of this study are to: (i) identify family responsibilities associated with moderately long working hours (41–60 hours a week); (ii) examine the relationship between moderately long working hours and three health outcomes (work-related poor health status, job stress and psychological distress); and (iii) analyze whether patterns differ by welfare state regimes in European countries.

Methods

The data have been taken from the 4th European Working Conditions Survey (EWCS) carried out in 2005 (31). The sample of the EWCS is representative of the persons in employment (employees and self-employed, according to the Eurostat definition) during the fieldwork period in each of the countries covered. In each country, the EWCS sample followed a multi-stage, stratified, and clustered design with a “random walk” procedure for the selection of the respondents at the last stage. Once a household was selected, it could not be substituted even if there was nobody at home, until four attempts to contact the interviewee had been unsuccessful (at different times and days). Non-eligible cases (35.4%) included vacant housing units, housing units with no workers, and housing units that were not residences. The refusal rate among eligible units was 24% and contact was not made in 9.4% of eligible units. These sample units were replaced until the target number of interviews was achieved. Trained interviewers conducted face-to-face interviews in the respondent’s own home. Details of the survey are reported elsewhere (32). For the purposes of this study, a subsample of all employees of the 25 EU Member States (EU-25) aged 16–64 years and working 30–60 hours per week was selected. In order to avoid the effect of extremely long working hours, people working >60 hours a week were excluded (1.5%). The final sample under analysis was composed of 9288 men and 6295 women.

Variables

Working hours were determined using two questions: “How many hours do you usually work per week in your main paid job?” and “How many hours a week on average do you work in job(s) other than your main paid job?”. Number of hours were summed and grouped into three categories (i) 30–40 hours (reference category), (ii) 41–50 hours, and (iii) 51–60 hours.

Country typology

Countries were grouped according to an adaptation of the Esping-Andersen typology (21), which was expanded to include all countries covered by the survey (33) and is similar to that used by Eikemo et al (34). There were five types of country groups: continental (Austria, Belgium, Germany, France and Luxembourg); Anglo-Saxon (Ireland and the United Kingdom); Eastern European (Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Lithuania, Latvia, Poland, Slovenia and Slovakia); Southern European (Cyprus, Greece, Spain, Italy, Malta and Portugal); and Nordic (Denmark, Finland, Sweden, and the Netherlands).

Health outcomes

Three health and well-being outcomes were selected. First, work-related poor health status was elicited through the question “Does your work affect your health, or not?” with two response categories. People who answered this question affirmatively were then asked “How does it affect your health?” consisting of checklist of 16 health problems. The second and third health outcomes were obtained based on this checklist, namely: work-related stress (a specific question of the checklist) and work-related psychological distress. The validity of a single-item measure of job stress has been already proven (35). Psychological distress was measured through four questions: overall fatigue, sleeping problems, anxiety, and irritability. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.77. People having at least one out of four psychological symptoms, were coded as having psychological distress.

Family responsibilities

Family responsibilities were measured through the partner/marital status (married or cohabiting and other), main contributor of household income (yes/no) and number of children at home (0, 1, and ≥2).

Employment conditions

Job category, assigned according to the respondent’s current occupation, was determined based on the 1988 International Standard Classification of Occupations 1 digit categories and subsequently grouped into three categories: upper (1 and 2), medium (3–5), and lower (6–9). Type of contract had five categories: permanent, fixed-term temporary, temporary employment agency, no contract, and other.

Data analysis

First, gender differences for all the dependent and independent variables were tested at the bivariate level using the chi-square test for categorical variables and the t-test for age. Second, family responsibilities associated with working 41–60 hours a week as compared to 30–40 hours were identified by fitting multiple logistic regression models for men and women separately and adjusting for age and employment conditions. Third, multiple logistic regression models adjusted for age and employment conditions were fitted in order to test the association between long working hours and family responsibilities. In order to test for an independent linear trend between health outcomes and working hours, logistic regression was performed fitting multivariate models including the predictor variable as continuous variable and the Wald test was used. All analyses included the weights derived from the complex sample design and were separated by gender and country group.

Results

General description of the sample

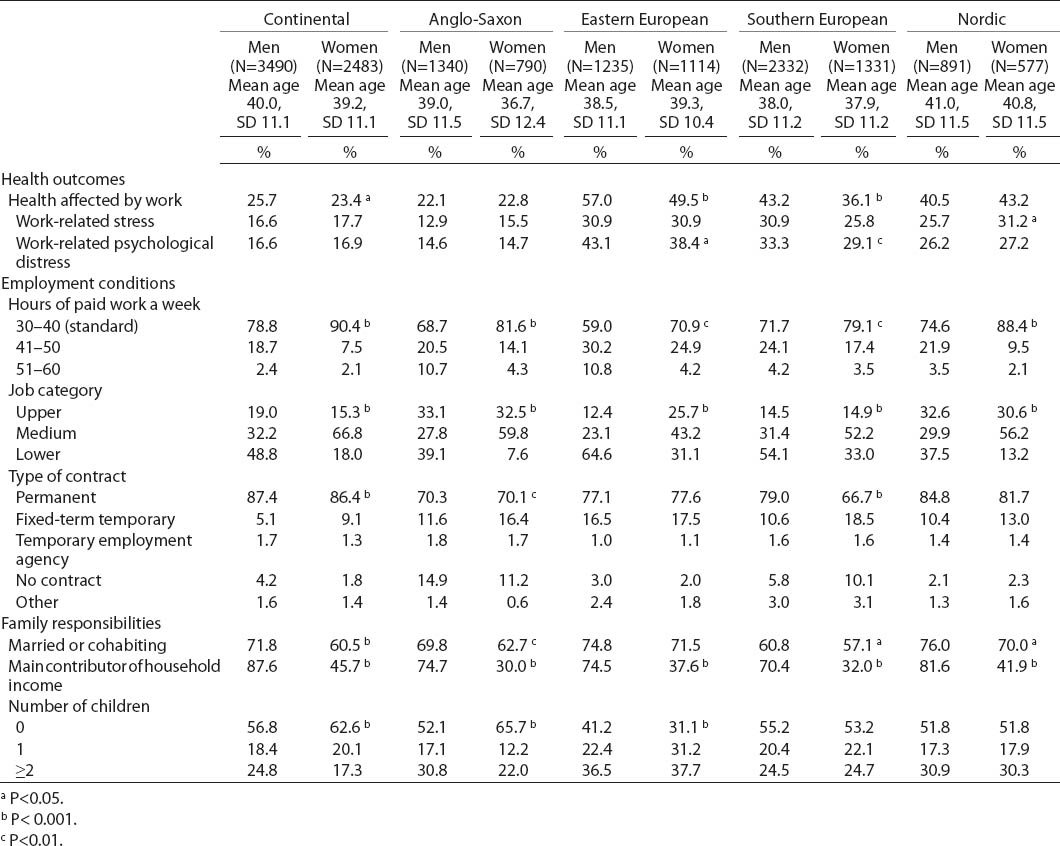

Table 1 shows a general description of the sample. Prevalence of poor work-related health outcomes was higher among Eastern and Southern European countries, whereas Continental and Anglo-Saxon countries had the best health outcomes. There were few gender differences. Working long hours was more frequent among men in Eastern European countries (41% of men and 29.1% of women) followed by Southern European countries (29.1% of men and 20.9% of women) and Anglo-Saxon countries (31.2% of men and 18.4% of women). The proportion of workers in the lower job categories was higher in Eastern and Southern European countries, mainly among men. Working with non-permanent contracts was also more frequent in these groups but, above all, among people from Anglo-Saxon countries. Additionally, the proportion of people with no contract was very high in Anglo-Saxon countries and among women from Southern European countries. Regarding family characteristics, in all countries, most people were married or cohabiting; being the main contributor of household income was more frequent among men.

Association between family responsibilities and long working hours

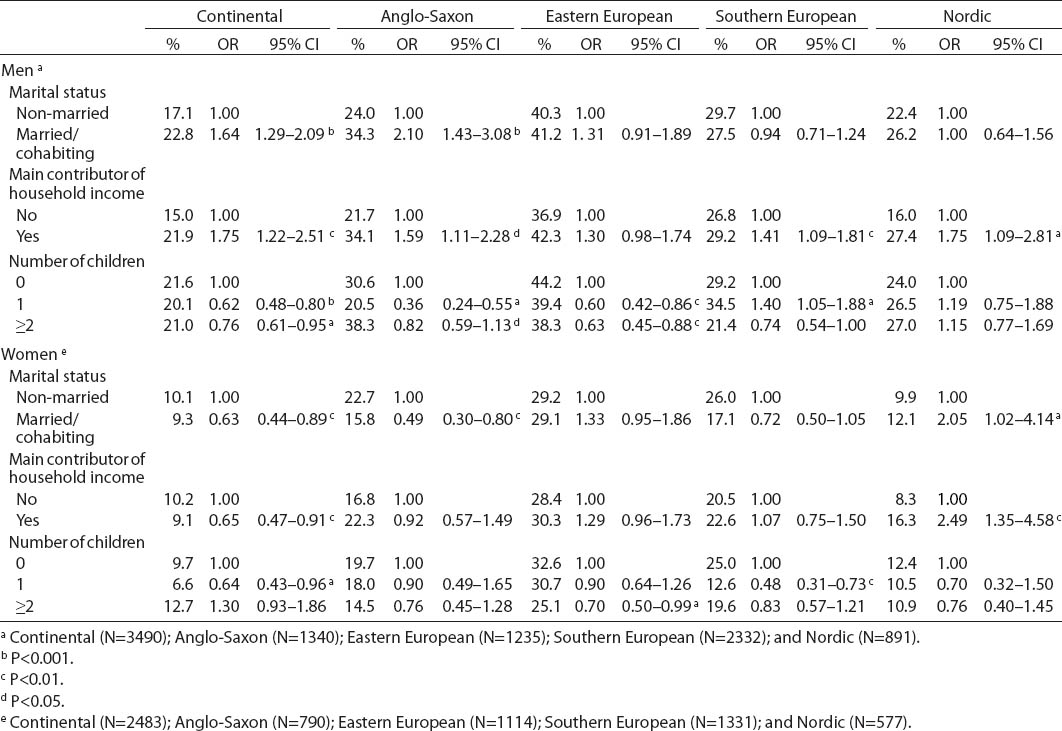

Table 2 shows family factors related to working 41–60 hours a week. Married or cohabiting men from Continental and Anglo-Saxon countries were more likely to work long hours, whereas the opposite was true for married women from these groups of countries. Conversely, being married was associated with long hours among women from Nordic countries [adjusted odds ratio (ORadj) 2.05, 95% confidence interval (95% CI) 1.02–4.14) but not among men. In Eastern European countries, being married or being the main contributor of household income was related to long working hours for both sexes, although the associations were only marginally significant. In all countries, being the main contributor of household income was associated with long working hours among men. Additionally, among women from Nordic countries, being the main contributor of household income was also related to working long hours (ORadj 2.49, 95% CI 1.35–4.58). In most groups, living with children was not significantly, with a few exceptions, associated with long working hours.

Table 2

Association of family responsibilities with working 41–60 hours a week compared with working the standard number of hours (30–40 hours) by sex and country group. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) adjusted for age and employment characteristics. Fourth European Working Conditions Survey, 2005.

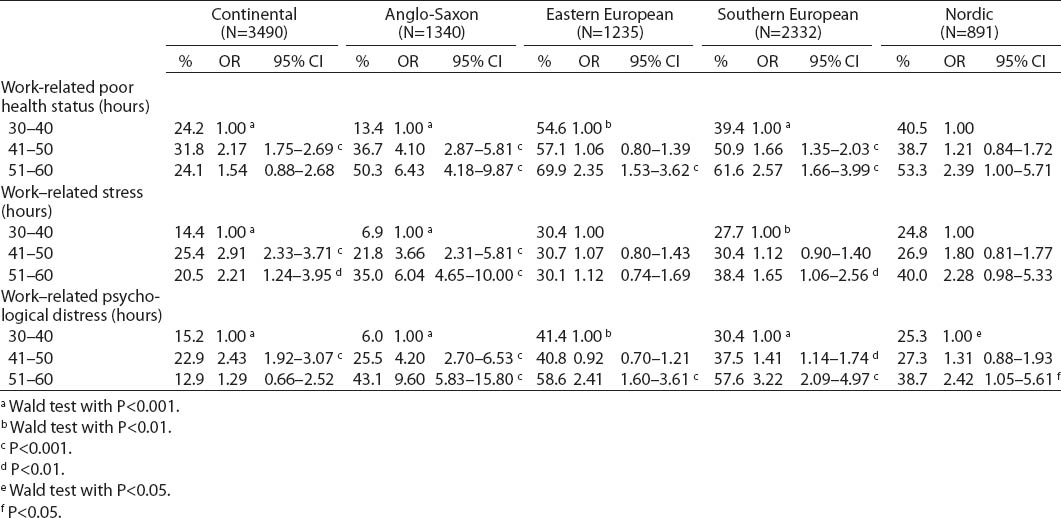

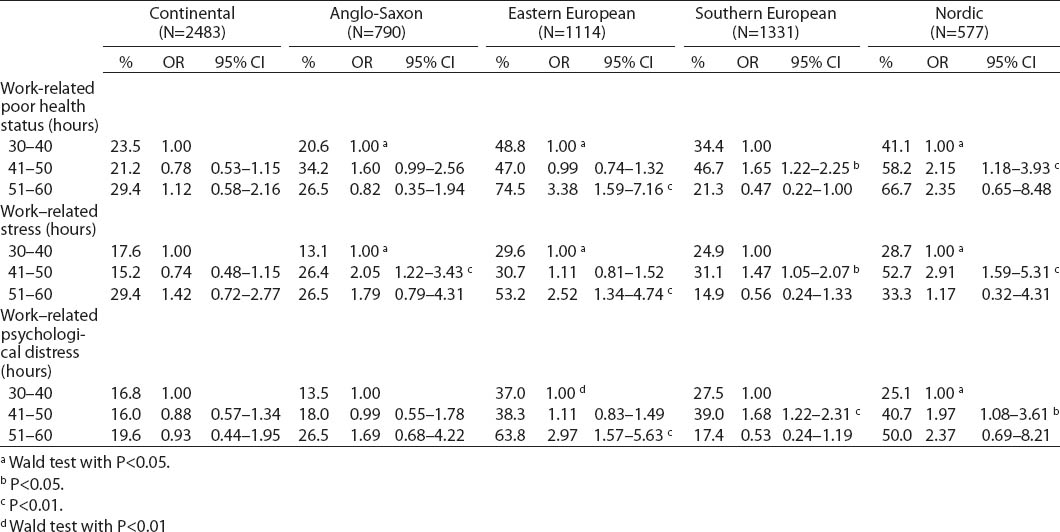

Association between long working hours and health

Long working hours were associated with almost all health indicators among workers of all groups of countries, except among women from Continental countries, and a gradient was found for most associations. Whereas in countries with male breadwinner models the association was stronger among men, it was similar among both sexes in Nordic countries and stronger among women in Eastern European countries. The number of significant associations was much higher among males (18 out of 30) than females (10 out of 30). Additionally, in most groups a positive trend between working hours and poor health status was found, but – among women from Southern European countries – the group with the highest weekly working hours (51–60 hours) showed the lowest prevalence of health problems. The magnitude of the associations was much higher among men from Anglo-Saxon countries (tables 3 and 4).

Discussion

As far as we know, this is the first study about moderately long working hours and health status carried out in a large and representative sample of the EU-25. There are three main findings: (i) Continental and Anglo-Saxon countries showed a typical male breadwinner model: married or cohabiting men were more likely to work long hours while the reverse was true among women; in countries with dual-breadwinner family models, married women were more likely to work long hours; (ii) except for females from Continental countries, in all countries, working long hours was related to poor health outcomes and a gradient was found, but the association was stronger and more consistent among men from Anglo-Saxon countries; and (iii) the association between long working hours and health was stronger among men in countries with male breadwinner models, similar among men and women from Nordic countries, and stronger among women from Eastern European countries.

Between-country differences in the association between family responsibilities and long working hours

According to the sexual division of labor, in all countries working long hours was more frequent among men. The pattern of associations with family responsibilities differed by country typology. As expected, in Continental and Anglo-Saxon countries that have male breadwinner models, married males were more likely to work long hours whereas the opposite was observed among married women. In Southern European countries, long working hours were not associated with marital status for either sex, but was related to being the main contributor of household income among men. As has been mentioned before, family financial stress is one of the main reasons for working long hours (14, 16–18) and in male breadwinner models, men are more likely to increase their working hours when families face economic difficulties.

Conversely, according to the dual breadwinner model, in Nordic countries being the main contributor of household income was positively related to working long hours among both sexes. Additionally, among women it was also associated with being married or cohabiting. In Eastern European countries – for both sexes – people who were the main contributor of household income as well as those who were married or cohabiting were more likely to work long hours, although the associations were only marginally significant. These similar gender patterns of associations between long working hours and family responsibilities are consistent with the expected findings in dual breadwinner models.

Working long hours was not associated with living with children in either group. Other studies have reported that the presence of young children has become less important over time as a reason for working long hours. Instead, in many countries household debt is associated with house prices (hence mortgage commitments) (18). According to a study of 17 industrialized economies between 1970–2003, most of the countries experienced a house price boom after the mid-1990s. During this period, housing price growth was particularly strong in Ireland, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom followed closely by Australia, Spain and a number of Nordic countries, where the pace of growth accelerated in more recent years (36).

Between-country differences in the association between long working hours and work-related health status

Previous studies have reported a damaging health effect of moderately long working hours that was attributed to their obligatory nature derived from family financial stress, as well as from low bargaining power (7, 8). They suggest that when family financial stress exists, breadwinners are forced to work long hours in order to increase household income. Additionally, due to their economic vulnerability they are likely to accept hard working conditions in order to keep their employment (17, 18).

In the present study, different patterns of association between long working hours and health by country typology emerged. The association between long working hours and poor health outcomes was much stronger among men from Anglo-Saxon countries. However, it should be noted that in these countries, among men working 30–40 hours a week (and to a lesser among women), the prevalence of poor health indicators was much lower than in the rest of the countries. Actually, among men working 30–40 hours a week, logistic regression models separated for sex and adjusted for job category, showed statistically significant differences between countries with Anglo-Saxons having the best situation for all health outcomes, whereas few between-country differences were observed among men working long hours (results not shown). Therefore, it seems that in Anglo-Saxon countries there is a dual labor market for men: people working 30–40 hours having a low prevalence of work-related health problems, whereas people working long hours are probably exposed to other poorer working conditions and have much poorer health status. These results are consistent with other studies that observe a polarization of jobs in the UK (37).

The UK is traditionally characterized as having limited state intervention and high salience of collective bargaining. As a result, worktime regulation is patchy and the UK is seen as a country typified by long male weekly working hours and a relatively high use of overtime (38). There is an individual “opt out clause” that permits individual employees to voluntarily work hours in excess of the 48-hour average weekly limit established by the European Working Time Directive (39–41). However, it has been suggested that workers may “opt” to work beyond this threshold not voluntarily but forced in different ways due to the need to earn more money or pressure exerted by the company for which they work (19, 42, 43).

In Continental countries, also with a male breadwinner model but with a much more regulated labor market, long working hours were associated with the three health outcomes among men, whereas there was no association among women. In these countries, the magnitude of the associations between long hours and health indicators among men were much lower than in Anglo-Saxon countries. The gender differences between these two country groups’ typologies can be explained by a male breadwinner model that presses men to work long hours more often when family financial stress exists (8) whereas the addition of a deregulated market in Anglo-Saxon countries could explain the large health inequalities among men with different working hours.

In Southern European countries, also with a male breadwinner model, long working hours were associated with poor health outcomes among both sexes but no gradient was observed among women. It should be noted that in these countries long working hours were not associated with marital status among either men or women. Nonetheless, men who were the main contributors of household income were more likely to work long hours. This can be the reason for a more consistent association between long working hours and health status among men.

In Nordic countries, people working long hours were more likely to report poor health outcomes and the magnitude of the association was similar for both sexes, although some differences were not statistically significant probably due to lack of statistical power. In Eastern European countries, which also have dual breadwinner models, unlike Nordic countries, the association between long hours and health outcomes was stronger among women. The different patterns found among women in these dual breadwinner typologies can be explained by the reduction in the support for families and children in a range of areas in Eastern European countries: family allowance, nursery provision, sick child leave, and parental benefits (28, 44). Moreover, traditional family values are much more common in post-communist countries than Western industrialized countries (29). Since long working hours were more frequent among married women, work conflict and overload derived from the double burden of job and family demands could partly explain our findings (45, 46). Moreover, these mechanisms probably act along alongside others such as impeded recovery. Women who work long hours and additionally have to allocate their non-working time to activities with a somewhat obligatory nature (such as household activities) are exposed to an additional source of strain impeding the recovery process during after-work hours (47).

Limitations

We have attributed the relationship between long working hours and health status to their mandatory nature derived from family financial stress but no information about their voluntary or involuntary nature or about family financial stress was collected in the EWCS. The consistency with previous studies as well as the association between long hours and the proposed conceptual model for understanding the relationship between long working hours and health status supports our interpretation. However further research is needed in order to confirm our hypothesis.

There are different welfare state regime typologies. Although there is no categorization that has been generally accepted as the standard, the one used in this paper has been highlighted as one of the most empirically accurate (48) and is consistent with the hypothesis about breadwinner typologies proposed in our study (22, 25).

We have measured health outcomes through three questions from the EWCS that have not been validated. However, they have face-validity, previous studies have showed the validity of a single-item measure of self-perceived health status (49) and of job stress, (35) and the scale used for measuring psychological distress had a good reliability. It can be argued that a common variance effect could exist since respondents were asked whether work affected their health instead of being asked about their health status. Nonetheless it should be noted that these are general questions that do not specifically ask about the relationship of health status with long working hours. Moreover, although the question is highly subjective, the predictor variable, long working hours, is self-reported but not subjective. Therefore, we can reasonably rule out a common variance effect related to negative affectivity. Finally, patterns of association differed by welfare state typologies according to the proposed conceptual model. Unfortunately, the EWCS did not include information about differences between respondents and non-respondents. However, the response rate was acceptable for the random walk procedure (32).

Finally, the EWCS collects information about being married or cohabiting but does not include more information about partner/marital status that could be related to economic vulnerability and family financial stress such as being separated, divorced, or widowed. For example, a previous study reported a detrimental health effect of long working hours among women who were separated or divorced (7). Moreover, the EWCS did not collect information about those health-related behaviors, such as smoking, shortage of sleep and no leisure-time physical activity that have been shown to be associated with working long hours (7, 8).

Concluding remarks

In the EU-25, working moderately long hours is associated with poor health outcomes although with varying magnitudes and gender patterns depending on welfare state regime typologies that could be related to family responsibilities and breadwinner models. The association between long working hours and health status is stronger among men in countries with male breadwinner models, primarily in Anglo-Saxon countries, similar in both sexes in Nordic countries and stronger among women in Eastern European countries. Finally, in all country typologies, among groups with stronger associations between long working hours and health status, working 41–60 hours a week was associated with having family responsibilities. This suggests that pressure to work long hours related to family financial stress may be a source of poor occupational health.