Depressive disorders have emerged as a major public and occupational health problem, especially in high- and middle-income countries (1, 2), where major depressive disorders ranked second in years lost due to disability in 2010. This burden of depression, measured with disability-adjusted life years, is increasing (3). Mood disorders are amongst the most impairing conditions among the working-aged population: it is estimated that approximately 35–50% of employees with depression will take short-term sick leave at some point during their job tenure (4). A Swedish study concluded 88% of the average yearly costs per patient (€17 300) were productivity losses due to sick leave and early retirement caused by depression (5).

Work-related factors may affect mental health and increase the risk of mental disorders (2). One of these factors is temporary employment, which is believed to be associated with an increased risk of mental health problems (6, 7) although null findings have also been reported (7). The hypothesized psychosocial and material pathways through which temporary employment may adversely affect mental health include increased job insecurity, lower income level, financial adversity, lack of promotion prospects, and greater exposure to hazardous working conditions (8). Due to an unstable labor market status, employees with temporary job contracts may at a higher risk of job loss and exclusion from the labor market when ill (9).

One reason for this mixed evidence may be that non-permanent employees are not a homogeneous group and several factors, including sociodemographics, might modify the association between employment status and mental health (7–14). A previous study from the same dataset used in this study found consistent socioeconomic inequalities in the onset, duration, and recurrence of work disability (15). Moreover, many studies with positive findings have not been able to take into account the health effects of potential non-employment among temporary employees during the follow-up period. This is important because unemployment has been associated with higher morbidity and mortality (16–18).

The few studies that have examined the association in stratified analyses suggest that temporary employment might be more detrimental to mental health among women than men (13, 14, 19). A low education level was associated with an increased risk of declining self-rated health among temporary employees, but not among those with a permanent contract (11). Temporary employment per se was a risk factor for increased depressive symptoms, irrespective of the level of education (11).

A further limitation of the evidence is a lack of studies that use detailed measurements of the work disability outcome, that is, studies which (i) separate the associations of temporary employment with the first and recurrent episodes of work disability due to depression and (ii) examine associations between temporary work and the length of disability, ie, how quickly the employee returns to work after the onset of the depressive episode. It is possible that temporary employment is related to some but not all of these aspects of work disability due to depression.

To address the limitations of earlier studies and add novel aspects to the existing literature, for the first time we examined the difference between the length and recurrence of the depression-related work disability of temporary and permanent workers. To overcome problems such as the heterogeneity of employment characteristics among temporary employees (freelance employees, seasonal workers, employees with a contract with a temporary work agency), non-specific measures of work disability, and small sample sizes, we focused on public sector employees with either a permanent or temporary contract in their organization and chose a diagnosis-specific disability outcome. More specifically, we set out to examine the association of type of employment contract with the onset, length, and recurrence of work disability due to depression in a large register-based sample. Moreover, we examined whether this association, if it existed, was dependent on the continuity of employment (having an ongoing employment contract), and whether sex, age or level of education modified these associations. The specific study questions were as follows: (i) Is the type of employment contract at baseline associated with the onset, length, and recurrence of work disability due to depression during a seven-year follow-up? (ii) Is this association, if one exists, dependent on employment continuity, ie, time with an ongoing employment contract during the follow-up? and (iii) Does sex, age, or education modify the association between type of employment contract and the onset, length, and recurrence of work disability due to depression?

Methods

Study design

The Finnish Public Sector Study cohort consists of full-time employees working for ten municipalities and six hospital districts in Finland (20) for >6 months in any year between 1991–2005 (N=151 901). The ethics committee of the Helsinki and Uusimaa hospital district approved the study. For the current study, we selected those cohort members (N=130 533) who were alive and working-aged (18–65 years) and not on disability pension or old-age pension on 1 January 2005 (the beginning of follow-up). Employees were linked to employers’ employment contract records and national health registers, including data on temporary and permanent work disability. This was done through the unique personal identification codes assigned to all permanent residents in Finland. We excluded employees with missing data on covariates (N=60), those who had not worked in the participating organizations for >5 years (on 1 January 2005, N=19 007), and those who had a government-subsidized temporary employment contract (a heterogeneous group consisting of long-term unemployed people and trainees, N=3 638). This resulted in a final analytic sample of 107 828 employees (83% of the original sample).

Work disability due to depression

Information on the dates of all periods of absence from work due to work disability (sickness absence and temporary and permanent work disability) due to a depressive disorder was derived from the national registers of the Social Insurance Institution of Finland and the Finnish Centre for Pensions. These include diagnosis-specific sick leaves >9 days and diagnosis-specific data on temporary and permanent, full-time and part-time disability pensions. The Social Insurance Institution of Finland pays compensation for sick leaves lasting for 10–365 days. If the disability lasts for over a year, the employee can apply for a disability pension (registers kept by the Finnish Centre for Pensions). Disability pension is usually first granted as compensation for a fixed term, assuming return to the labor market after rehabilitation. The records used in this study thus covered all types of uninterrupted periods of absence from work.

The main diagnoses for disability periods assigned by the treating physician were available for all sick leaves and disability pensions and were coded according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) (21). We examined these data for disability due to a depressive episode (F32), a recurrent depressive disorder (F33), and persistent mood (affective) disorders (F34) during 2005–2011. We included the following variables in our study: (i) Onset of work disability episodes due to depressive disorder between 1 January 2005 and 31 December 2011 coded as 1=beginning of disability episode due to depressive disorder; 0=no disability episodes due to depressive disorder; (ii) Length of disability episode due to depressive disorder (from the beginning of disability compensation until the end of compensation). Length was categorized as <2 months, 2–4 months, 4–8 months, 8–12 months, and >12 months; (iii) A recurrent disability episode due to a depressive disorder among those who had ≥1 prior work disability period and returned to work, coded as 1=a new disability episode due to depressive disorder after the end of the preceding disability episode; 0=no new disability episodes due to depression, disability pension with diagnosis other than F32-F34, old-age pension, death, or end of follow-up.

Employment contract

Each individual was exclusively classified as either a permanent or temporary employee on 1 January 2005 (the beginning of follow-up). Temporary employment is always an employment contract of fixed duration set by the employer (includes ending day), and a permanent employment contract is an open-ended contract.

To investigate whether employment continuity (ie, the duration of employment during the follow-up) had an impact on the association between employment status and work disability, we calculated the percentage of time for which each employee was employed in the participating organizations during the follow-up. We obtained these data from the employers’ records.

Covariates and effect modifiers

To examine whether the association between temporary employment and depression-related work disability differed according to demographic background, we studied the possible effect modification of sex, age and level of education (assessed at baseline). This is important because earlier evidence suggests that the effects of temporary employment on health might be more adverse among women (13, 14, 19) and those with a lower level of education (11).

Additional covariates were chronic somatic disease and previous work disability periods due to any mental or behavioral disorder (ICD-10 codes F00-F99) during 2004 (yes versus no). Employees’ age and sex were obtained from the employers’ records. Age was classified into quartiles (1=18–35, 2=36–44, 3=45–52, and 4=53–65 years). Statistics Finland provided information on education classified as higher (tertiary level: polytechnic, university education), intermediate (upper secondary level), or basic (lower secondary level or less: nine years of comprehensive education), using the Finnish Standard Classification of Education 2011 (22).

The presence of chronic physical disease at baseline (no versus yes) was ascertained from the national health registers. Information regarding diagnosed prevalent hypertension, cardiac failure, ischemic heart disease, diabetes, asthma or other chronic obstructive lung disease, and rheumatoid arthritis were obtained from the Drug Reimbursement Register maintained by the Social Insurance Institution of Finland. Data on malignant tumors diagnosed during the preceding five years was obtained from the Finnish Cancer Register, which covers all diagnosed cancer cases in Finland.

Statistical analysis

To examine associations between the type of employment and the onset of work disability due to depression, we used Cox proportional hazard regression for recurrent events. In this way, we were able to analyze all the episodes of the same person, in cases where one person had several work disability episodes. Correlations between observations of the same person were taken into account by calculating standard errors using the robust sandwich variance estimate. This approach yields consistent estimates of the covariance matrix without making distributional assumptions, even if the assumed model is incorrect (23).

Follow-up began on 1 January 2005 and ended at the beginning of the disability episode due to a depressive disorder (codes F32-F34), disability pension with diagnosis other than F32-F34, old age pension, death, or end of follow-up (31 December 2011), whichever came first. We estimated hazard ratios (HR) with their 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for type of employment (temporary versus permanent), adjusted for age, sex, education, chronic somatic disease, and previous work disability periods due to any mental or behavioral disorder.

To analyze the length of the disability period (a variable with five categories) as outcome, we used a multinomial logistic regression procedure, calculating cumulative odds ratios (COR) and their 95% CI for type of employment as a predictor variable.

We used Cox proportional hazard models for recurrent events to examine the associations between type of employment and the recurrence of work disability due to depression. Follow-up was from the end of the prior disability episode (codes F32-F34) to the beginning of the next disability episode (codes F32-F34), disability pension with diagnosis other than F32-F34, old age pension, death, or end of follow-up (31 December 2011), whichever came first.

The data on the percentage of time employed, ie, with an ongoing employment contract, during the follow-up (prior to disability pension, old-age pension, or 31 December 2011) was used in a sensitivity analysis to investigate whether actually being employed during the follow-up had an impact on the association between employment status and work disability (study question ii). In two separate analyses, we excluded those employees who were employed >50% of the time and then those who were employed >75% of the time.

Possible effect modifications (study question iii) were tested using interaction terms (sex × employment contract; age × employment contract; education × employment contract) and were adjusted for covariates.

We used SAS statistical software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) for all analyses.

Results

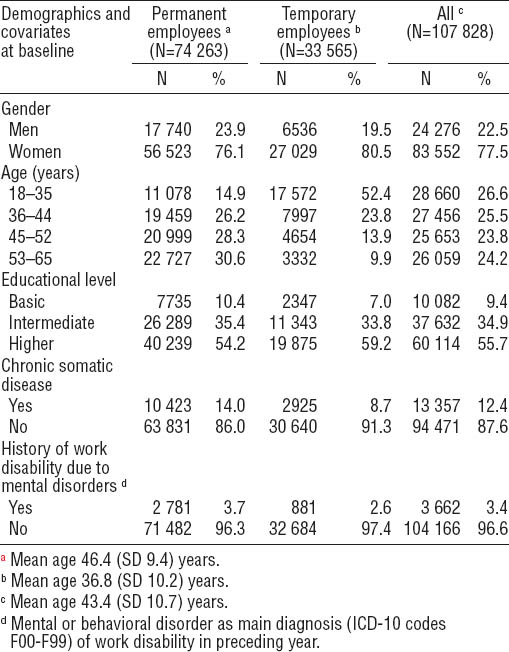

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics by type of employment contract. Of all the employees, 69% had a permanent and 31% a temporary contract. Temporary employees were younger, more often women, and more often highly educated than permanent employees. In this unadjusted comparison, temporary employees were less likely to have chronic somatic diseases or a history of work disability due to mental disorders than permanent employees.

At the beginning of the follow-up, 90% of the permanent (N=66 383) and 67% of the temporary (N=22 383) employees were employed by the participating organizations. The rest of the study participants (ie, 10% of permanent and 33% of temporary employees), although not employed by the participating organizations at the start date of the follow-up, had been employed during the preceding five years and thus were included in the analyses. The role of employment continuity is studied further in sensitivity analyses.

Temporary employment and onset, length, and recurrence of work disability due to depression

During the mean follow-up of 3.09 years [standard deviation (SD) 1.97], we detected 9146 episodes of work disability due to depression among 74 216 permanent employees (12.3%) and 3862 episodes among 33 559 temporary employees (11.5%). The time for the onset of an episode during the follow-up was slightly longer among temporary (mean 3.35, SD 1.96, years) than permanent (mean 2.98, SD 1.97, years) employees. The mean number of episodes were 0.12 (range 0–11) and 0.12 (range 0–14) for permanent and temporary employees, respectively. Temporary employment was not associated with the risk of depression-related work disability in the multivariable adjusted model (HR 1.02, 95% CI 0.97–1.08) (table 2).

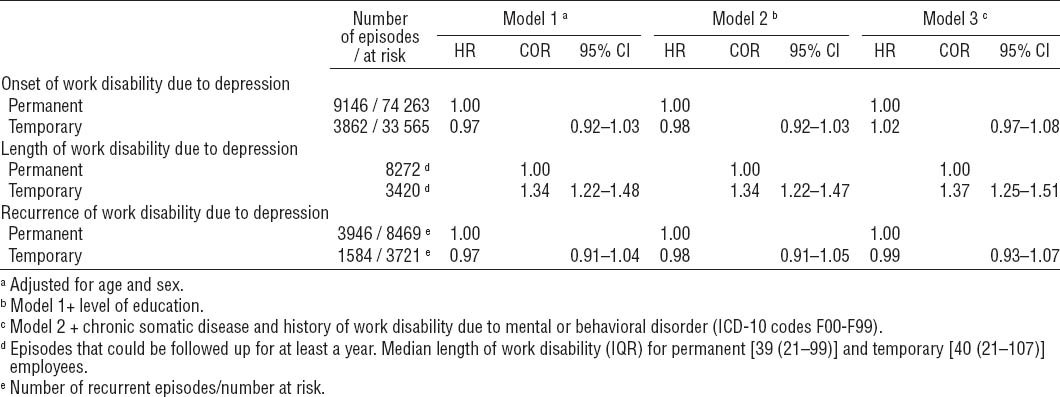

Table 2

Association between type of employment and onset, length, and recurrence of work disability due to depression (ICD-10 codes F32-F34). [HR=hazard ratio: 95% CI=95% confidence interval; IQR=interquartile range; COR=cumulative odds ratio]

A total of 8223 employees had at least one depression-related work disability episode. Of these, 2491 (30%) were temporary employees, which corresponds to the proportion of temporary employees in the study population. For the analyses of the length of work disability, we were able to follow up 11 692 disability episodes for at least a year [median length 40 days, interquartile range (IQR) 21–102]. Of these, 10 598 (91%) ended during the follow-up (median length 34 days, IQR 20–70). Of all disability episodes due to depressive disorder, 63% ended in <2 months, 14% in 2–4 months, 8% in 4–8 months, 4% in 8–12 months, and 11% lasted >12 months. The disability episodes that exceeded a year (including episodes that did not end during the follow-up) were temporary or permanent disability pensions. The distributions of the length of the work disability episodes according to employment contract, and to sex, age, and education stratified by type of employment contract, are presented in supplementary table A (www.sjweh.fi/data_repository.php). The median length of disability episode was 39 days (IQR: 21–99) among permanent employees, and 40 days (IQR: 21–107) among temporary employees. In the multivariable adjusted model, temporary employment was associated with a 1.37-fold (95% CI 1.25–1.51) increased risk of longer disability episode (table 2).

Of the depression-related work disability episodes that had ended in return to work, 45% (N=5530) (permanent: 47%; temporary: 43%) recurred. The follow-up time for the onset of a recurrent episode was 26 months on average (SD=23), with no difference according to type of employment contract. Type of employment contract was not associated with the recurrence of work disability due to depressive disorder (HR=0.99, 95% CI: 0.93–1.07) (table 2).

Role of employment continuity

To further examine the robustness of the associations between type of employment and work disability due to depression, we examined whether the continuity of employment, ie, the percentage of time for which the employee was employed (had an ongoing employment contract), had an impact on the association between type of employment and work disability. Those employees who were employed <50% of the time during the follow-up were excluded. There were 11 064 episodes of depression-related work disability: 8091 among permanent employees, and 2973 among temporary employees (95% of the original sample). In this sample, temporary employment was associated with a slightly decreased risk of depression-related work disability after adjustment for age, sex, level of education, presence of chronic somatic disease, and preceding work disability due to mental or behavioral disorder (HR 0.91, 95% CI 0.85–0.97). Temporary employment was marginally associated with the length of disability episodes (COR 1.11, 95% CI 1.00–1.23), and was not associated with the recurrence of work disability due to depressive disorder (HR 1.00, 95% CI 0.92–1.07). [Supplementary table B (www.sjweh.fi/data_repository.php].

We further excluded those employees who were employed <75% of the time during the follow-up. This sample had 10 436 episodes of work disability due to depression (89% of the original sample). The results resembled those presented in supplementary table B: Temporary employment was associated with a decreased risk of work disability due to depression after adjustments (HR 0.91, 95% CI 0.85–0.97). Temporary employment was not associated with the length of disability episode (COR 1.01, 95% CI 0.90–1.13), nor with recurrence of disability (HR 0.99, 95% CI 0.91–1.07). (Data not shown, but available upon request from the first author.)

Effect modification by sex, age, and education

We examined possible effect modifiers for the association between employment contract and the onset of depression-related work disability. No effect modification by sex, age, or education was observed in the association between employment contract and the onset of a work disability period (P>0.25) [supplementary table C (www.sjweh.fi/data_repository.php].

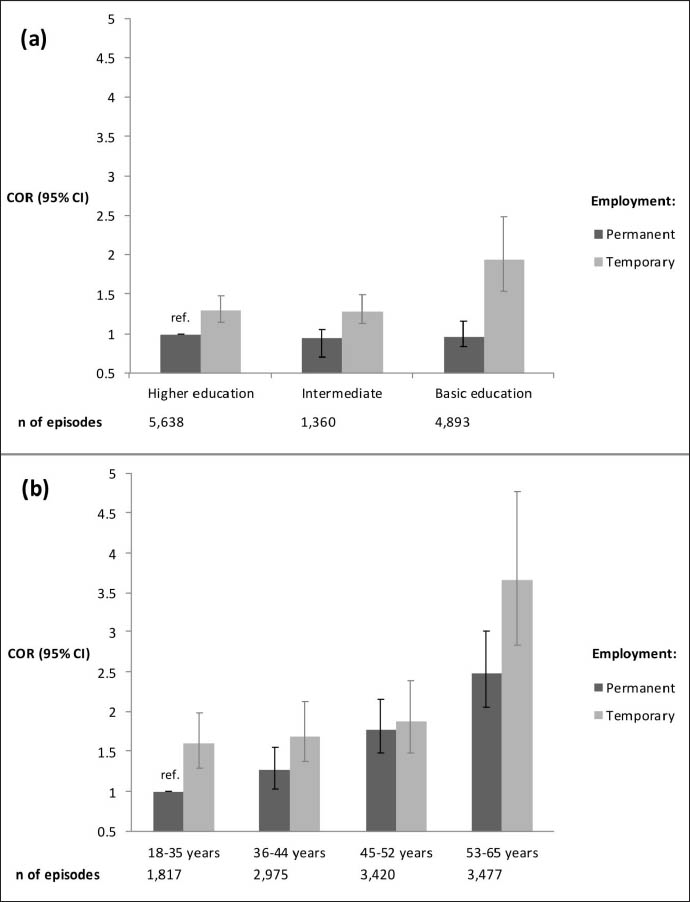

With regard to length of disability episode, there was an interaction between “education × employment contract” (P=0.02). This interaction is illustrated in Figure 1a. There were no differences in the length of disability episode according to education among permanent employees. As shown in supplementary table C, in the multivariable adjusted model, compared to permanent employees with higher education (ie, referent), temporary employment combined with higher or intermediate education was associated with a moderately increased risk of a longer disability episode (COR 1.30, 95% CI 1.14–1.48 and COR 1.29, 95% CI 1.12–1.49, respectively). However, temporary employment combined with basic education was associated with a 1.95-fold (95% CI 1.54–2.48) risk of longer disability episode compared to permanent employment combined with higher education (supplementary table C). The median length of disability episode was 41 days (IQR 21–98) among permanent employees with higher education, and 51 days (IQR 24–166) among temporary employees with basic education (supplementary table A).

Figure 1

Risk of longer disability episode due to depressive disorder: (1a) by level of education [reference category (1)=permanent employment, higher education]; (1b) by age [reference category (1)=permanent employment, age 18–35]. Cumulative odds ratio (COR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) adjusted for sex, somatic disease, and prior work disability due to mental or behavioral disorder.

We also found that age modified the association between type of employment and the length of work disability episode (P for interaction=0.04), which is illustrated in figure 1b. In the multivariable adjusted model shown in supplementary table C, age was associated with the length of disability episodes among both permanent and temporary employees, but aging (>52 years) temporary employees were at a considerably higher risk of longer disability episodes than young (18–35 years) permanent employees (COR 3.67, 95% CI 2.83–4.76). The median length of disability episodes was 31 days (IQR 19–59) among young permanent employees, and 61 days (IQR 25–354) among aging temporary employees. It is also noteworthy that of the disability episodes, the percentage of depression-related disability pensions (episodes lasting >12 months) was 3% among young permanent employees, and the corresponding percentage among aging temporary employees was 24%. (Supplementary table A).

No effect modification of sex, age, or education, explaining the recurrence of work disability due to depression, was observed (P>0.25) (Supplementary table C).

Discussion

In this prospective cohort study of 107 828 Finnish public sector employees, temporary employment was associated with slower return to work after a disability episode, as indicated by the length of the episode. This association was not attributable to chronic somatic diseases or a recent history of work disability due to other mental or behavioral disorder. However, type of employment was not associated with the onset or recurrence of work disability due to depression.

Our outcome variable was a composite measure of various indices of depression-related work disability, which might have slightly different determinants. The observed association in the analysis of the length of disability episodes is likely to particularly reflect the predictors of prolonged sick leave (4–12 months) with a depression diagnosis, as these were more prevalent among temporary than permanent employees. However, delayed return to work is also likely to imply a transfer from sick leave to work disability pension (either fixed-term or permanent). Therefore, work disability in the Finnish social security system comprises a continuum, justifying the composite measure of disability.

To control for bias caused by non-employment and the associated health hazards, in our sensitivity analyses we included only those employees who were employed (had an ongoing employment contract) >50% of the time during the follow-up. We found that among this group, temporary employment actually slightly decreased the risk of onset of depression-related work disability. Temporary employment has been associated with a lower rate of sick leave and fewer sick leave days in previous studies (7). While it is possible that lower levels of sick leave among temporary employees reflect their better health, lower sick leave rates may also be related to job insecurity and sickness presenteeism (24, 25). Possibly due to higher job insecurity, temporary employment has been associated with not taking sick leave despite fulfilling the criteria for depressive disorder (26). In the sensitivity analyses, the association between temporary employment and slower return to work was weaker but still significant. This result is in accordance with a previous study among individuals with a fixed-term disability pension, which showed that those who had an ongoing employment contract throughout the whole disability period were twice more likely to return to work after this period than those without such contracts (27). It thus seems that ongoing employment contract promotes return to work among temporary employees.

There at least three plausible explanations for the sensitivity analyses’ results with return to work as the outcome variable. First, being unemployed or otherwise outside the labor market may in itself increase the risk of depressive disorder (16). Second, those in employment for the majority of the follow-up may have been healthier at baseline due to health-related selection. This suggests that those with milder depression (healthier employees) had better working capacity than those with more severe depression. In sum, our findings may have been affected by the “healthy worker effect”: less healthy employees are more prone to select out, that is, they are ordinarily excluded from employment and less likely to gain new employment (7, 28). Third, it is possible that those in employment for the majority of follow-up time had already gained permanent employment, making return to work easier. Mental disorders reduce the likelihood of getting a permanent employment contract (29, 30) and increase the likelihood of unemployment (31). In a similar vein, those employees who gained a permanent employment during follow-up had lower mortality than those who constantly remained in permanent employment (17).

Finally, our study also shows several subgroups of temporary employees at a high risk of long disability episodes: although temporary employment increased the risk of longer disability episodes regardless of education level, the risk was more pronounced among those with a lower level of education and among employees >52 years. The chances of less educated and older people (re-)entering the labor market are rather poor across Europe, also in Finland, despite recent improvements (32–34). Hence, it is possible that in these cases, people may have no longer had a job to which they could return.

Since the length of the disability episode is a marker of the severity of depression, one explanation concerns treatment and access to care. It is possible that older and less-educated temporary employees do not seek help or receive equal treatment, or are not granted sufficient psychotherapy, for example. Inequality in access to care, in this case occupational healthcare, is a plausible explanation, especially when employment contracts are short and discontinuous.

Strengths and limitations

We were able to overcome some of the limitations of previous studies because we had a large register-based sample that allowed us to examine the relation ship between the employment contract and depression-related work disability without any loss of individuals at follow-up. Due to our large sample size, we had sufficient statistical power to detect interaction effects. Thus, our study contributed to existing evidence by examining the effect modifiers of the association between type of employment and work disability due to depression.

The study also has some limitations. The healthy worker effect may lead to underestimation of the effect of temporary employment, as health-related selection is likely to keep less-healthy employees in temporary positions (17, 29). Although the models were adjusted for recent episodes of work disability due to mental or behavioral disorders during the year prior to the study baseline, we were unable to control for all previous mental disorders over the life course. Thus, the temporal order of the associations cannot be determined.

Although we tested several effect modifiers, it is possible that some factors still confound, mediate, or moderate the observed associations. For example, an earlier study of the same cohort showed that temporary employees had a better psychosocial work environment than permanent employees (35). The authors concluded that this was possibly explained by differences in the structure of the work situation: while temporary employment may mean more insecurity, it may also provide more opportunities to focus on specific tasks at work. Permanent employees may be more obliged to maintain daily routines. Another study from a Swedish small town cohort (36) found that the association between temporary employment and psychological distress was partially explained by socioeconomic factors and perceived job insecurity. Yet another study of the same cohort (37) found that perceived job insecurity can lead to poorer mental health regardless of the type of employment contract.

We assessed employment contract at baseline only; some misclassification may have occurred due to changes in employment contract during follow-up. In a previous study (38), receiving a permanent contract after temporary employment was associated with an increased risk of medically certified sick leave, but no change was observed in health, health behavior, or work characteristics.

Finally, our study population was rather homogenous, comprising mainly female Finnish public sector employees (although the absolute number of men was also high), which may limit the generalizability of our findings. Future research should examine these associations in the private sector, other ethnic groups, and other countries.

Concluding remarks

In this study, we observed longer depression-related work disability episodes among temporary employees, which was especially pronounced among older workers and those with a low level of education. An ongoing employment contract might protect temporary employees from the risk of labor market exclusion. Further research is needed to determine whether interventions to promote return to work should focus on removing obstacles to maintaining or gaining employment or on improving the availability and effectiveness of therapy among temporary employees with depression.