There are more than 3 million welders worldwide, and welding is an important source of occupational artificial ultraviolet radiation (UVR). UVR is part of the electromagnetic radiation spectrum with wavelengths from 100 nanometers (nm) to 400 nm. There are three types of UVR: UV-A 320–400 nm, UV-B 280–320 nm and UV-C 100–280 nm. The wavelength range is 400–780 nm for visible light and 780 nm–1 mm for infrared radiation. The cornea absorbs 100% of the UV-C light (1–3). Animal studies show that UVR in the range 295–370 nm is absorbed in the lens, and wavelengths from 295–320 nm are the most effective in producing lenticular damage (4).

An outdoor worker in Denmark (gardener) will receive on average 22 400 J/m2 per year (min-max 5400–66 900 J/m2 per year) of solar UVR, while an indoor worker on average receives 13 200 J/m2 per year (min-max 1700–84 100 J/m2 per year) (5). For comparison, if a welder were to receive the same amount of UVR as an outdoor worker in Denmark, then the welder should be exposed to the welding flame between 1-4 seconds per working day for UV-B radiation and 4–30 seconds per day for UV-A radiation (6–8). Unlike outdoor workers, welders risk exposure to UV-C radiation.

Welders are exposed to radiation both directly and indirectly. Welding radiation can penetrate the welding gear from the side (9). Also, welders may be exposed when the protective gear is off, eg, by accidental ignition or exposure as a bystander (10). Using a questionnaire, a study of 181 Danish welders in 1983 found that only 1.7% did not use protective eye gear at all, 76% had ever had photo keratitis, and within the last year, 49% had had photo keratitis. Photo keratitis was caused by own welding light in 24% of cases, 29% by others welding light, and 47% by both own and others welding light (6). In another study, 116 welders with >10 years of work experience had, on average, 12 episodes of photo keratitis in their work life (11).

Like UVR, infrared radiation has been shown to cause cataract in animal studies (12). Few studies of glassblowers and steelworkers have reported an increased frequency of cataract when exposed to infrared radiation from hot glass or metal (13, 14). Both the sun and welding emit infrared radiation. However, the intensity of infrared radiation from welding is considered to be low and probably does not constitute a risk in causing cataract (6).

A clouding or opacity of the lens, cataract is a multifactorial illness associated with increasing age, diabetes, exposure to ionizing radiation, family history of cataracts, previous eye trauma or inflammation, previous eye surgery in the posterior part of the eye, prolonged use of corticosteroid medication, low socioeconomic status, smoking and excessive exposure to UV-B (sunlight) (15). Studies have shown that UV-B from sunlight can cause changes in the lens protein and impair cell functions resulting in oedema and vacuolization (16). During a lifetime, it is the accumulated amount of UV-B radiation that causes damage to the lens (17). For 48 years, cataract has been treated by phacoemulsification and replacement surgery.

The prevalence of cataract replacement surgery was reported in two large studies. The Blue Mountain’s Eye Study included 3654 persons from two geographical areas in Australia and reported a prevalence of 1.6% for those aged <65 years, 4.4% for 65–74 years, 17.2% for 75–84 years and 35.4% for >85 years (18). The US Framingham Eye Study included 2477 persons aged 52–85 years and found a cataract prevalence of 4.5%, 18.0% and 45.9% for <65, 65–74, and 75–85 years, respectively (19).

We identified seven cross-sectional studies with 31–117 welders addressing the risk of cataract and one case–control study with 168 welders. Findings are conflicting with three studies reporting an increased risk (11, 20, 21) and five studies reporting no risk (10, 22–25). In many studies, the power to detect an increased risk for cataract is limited and only three adjusted for potential confounders of age and diabetes (21, 23, 25).

The aim of this study was to examine if occupational exposure to UVR from metal welding increases the risk of cataract by a design taking several limitations of earlier studies into account. In addition to effects of ever-welding, we examine risk according to cumulated years of welding.

Methods

The study is a register-based follow-up that examines the risk of a diagnosis of cataract according to welding exposure.

The cohort of welders was originally designed to identify the risk of lung cancer and welding conferred by stainless steel welding and later was also used for studying cardiovascular diseases, asthma, and infertility (26–30). The construction of the metal welders’ cohort is comprehensively described in earlier publications (27, 28, 30) and briefly summarized here.

Cohort of welders

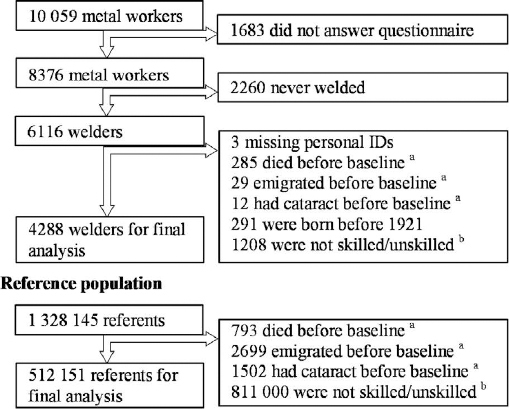

A cohort of 10 059 metalworkers, who had been employed for ≥1 year between April 1964 and December 1984 in ≥1 of 75 different metal shops in Denmark, was established in 1984 based upon company roster and records from the Danish Pension Fund (27). The 75 metal shops employed about 60% of all Danish stainless steel (SS) welders and five of the larger metal shops also handled mild steel (MS). Shipyards were excluded due to possible asbestos exposure. All participants were employed as MS welders, SS welders, SS grinders or non-welding/grinding production workers. Figure 1 provides an overview of exclusions resulting in a final database of 4288 metal arc welders with complete information. In autumn 1986, the cohort was mailed a questionnaire that included work history in the years 1950–1985, years of welding per decade in MS and/or SS, and hours of welding per day. Baseline was defined as 1 January 1987. Social group was identified from Statistics Denmark’s registration in 1985 and defined by job title. The categories for social groups were chief executive, self-employed, white-collar worker, skilled blue-collar worker, unskilled blue-collar worker, student or retired. Approximately 80% of the welders belonged to social group skilled and unskilled workers. For a better match between welders and reference group, we excluded all other social groups from both welders and referents.

Reference population

We established an external reference group based upon the Danish population registry including all males born between 1 January 1921–1 April 1964, who had worked for ≥1 year in any Danish company between April 1964–December 1984, and who were alive on 1 January 1985, resulting in a total of 1 328 145 referents. Figure 1 provides an overview of exclusions resulting in a final database of 512 151 referents for the final analysis. Self-report data were not obtained from this external reference group.

Outcome ascertainment

Using registry linkages, we retrieved data on cataract diagnosis and operations from public hospitals recorded in the National Patient Registry (NPR) since 1977, which from 2004 also included examinations at private hospitals. Moreover, we retrieved data on cataract operations from private ophthalmologists recorded in The National Health Insurance Service Registry (NHI) since 1990. Patients that paid for the operation without reimbursement were registered in the DUSAS register since 2002. Before 2002 such privately paid operations were rare (31). Thus, almost all cataract operations were performed at public hospitals before 2002 (31) and the registers are almost complete for operations performed between 1977–2002. In 2002–2004, some operations are missing from the registers since at that time it was not mandatory for private hospitals to register and there was a politically induced shift from public to private hospitals. However, even after reporting to public health registers became mandatory for all cataract operations performed from 2004 onwards, the health registers are not complete because of underreporting of cataract operations performed in private hospitals (31). The number of operations performed in private hospitals from 2002–2012 without registration is unknown and lost to our study.

Until the end of 1993, diagnoses were coded according to an extended Danish version of the International Classification of Diseases, Revision 8 (ICD-8), and after that date according to ICD-10. Private ophthalmologists coded no diagnoses, but only operations performed using a unique coding. Operations were coded according to the Danish Operations and Treatment Classification before 1996 and the Danish SKS Classification after 1996.

All dates for cataract operations and/or diagnoses were linked to the personal identification numbers. Cataract was divided into two groups, regular cataract and irregular cataract. Irregular cataract was defined as cataract with known causes such as trauma, juvenile/congenital, diabetes or other illness or medication. Regular cataract was defined as not containing a main or secondary code for irregular cataract and, if there were an operation code, it was for an ordinary phacoemulsification cataract surgery (table 1).

Table 1

Categorization of regular and irregular cataract. [Meds=medication.]

The first date for first cataract diagnoses or operation was used as the outcome date. If only the operation date was available, then the operation date was used as diagnosis date. It is not possible to differentiate between the different kinds of cataract, since too many cataract diagnoses are registered with the general diagnose code.

Since diabetes may cause cataract, all hospital diagnoses in the NPR register with diabetes or illnesses caused by diabetes were linked to the personal identification numbers. Persons that ever had a diabetes code were presumed to have diabetes, regardless whether the diagnosis was made before or after cataract diagnose. Diabetes patients often have diabetes years before they are diagnosed. The registry is not complete, since many patients only are treated at their general practitioners and never come into contact with a hospital. There are no codes in NHI for diabetes diagnoses.

Welders’ and referents’ personal identifications numbers were linked with Statistics Denmark registers with birth, emigration, death, and social group.

The questionnaire gave information about how many years per decade of welding in MS and/or SS. Welding-years was the accumulated amount of years working as a welder over the decades. There was no information about the use of protective gear.

Statistical analysis

We examined the risk of diagnosis and/or operation for cataract in welders and the reference group from 1 January 1987 through 31 December 2012 using Cox regression. The outcome date was taken as date of the first registration of cataract diagnosis and/or operation during follow-up. Data were censored by date of death, first date of emigration or diagnosis of cataract, which ever came first. There was no loss to follow-up since Danish registers are complete. SAS 9.3 was used for Cox regression analysis conditioned on years from the start of follow-up (1 January 1987) with welding status (ever welded yes/no) as the independent variable and with adjustment for age (continuous), diabetes (yes/no), and social group (skilled/unskilled blue-collar labor). In subsequent analyses, we examined the association between cumulative number of welding years (continuous) and risk of cataract.

Results

Characteristics of the welders and the referents are shown in table 2. There were 4288 male welders [mean age 40.6, standard deviation (SD) 10.4, years] and 512 151 male referents (mean age 40.3, SD 11.6, years) included in this study. There were no differences in mean age at death, percentage with diabetes diagnosis, or emigration between welders and referents. The percentage of skilled workers was higher among the welders than referents.

Table 2

Characteristics of welders and referents.

| Welders | Referents | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| N | % | N | % | |

| At baseline | 4288 | 14.9 | 512 151 | . |

| Age (years) a | ||||

| <25 | 227 | 5.3 | 46 128 | 7.9 |

| 26–35 | 1127 | 26.3 | 160 579 | 30.7 |

| 36–45 | 1580 | 36.9 | 142 985 | 27.8 |

| 46–55 | 917 | 21.4 | 94 874 | 19.2 |

| 56–66 | 437 | 10.2 | 67 585 | 14.6 |

| Dead | 1029 | 24.0 | 111 215 | 29.5 |

| Emigrated | 120 | 2.8 | 14 725 | 2.9 |

| Skilled | 3271 | 76.3 | 245 296 | 47.9 |

| Unskilled | 1017 | 23.7 | 266 855 | 52.1 |

| Diagnosis of diabetes | 403 | 9.4 | 47 645 | 9.3 |

| Years welded | ||||

| 1–10 | 1743 | 40.7 | . | . |

| 11–20 | 1324 | 30.9 | . | . |

| 21–30 | 879 | 20.5 | . | . |

| 31–48 | 342 | 8.0 | . | . |

The number of cases with regular cataract operation and/or diagnosis was 266 (6.2%) for welders, of which 242 (5.6%) had a cataract operation, and 29 007 (5.7%) referents had a cataract diagnosis and/or operation, of which 25 722 (5.0%) had a cataract operation. For irregular cataract operation and/or diagnosis, it was 54 (0.6%) for welders and 7359 (1.4%) for referents.

The incidence of a cataract diagnosis was not higher among welders compared to referents (table 3) and similar results were obtained for cataract operation (data not shown). We performed a sensitivity analysis only including welders and referents aged >50 years at baseline (N=814 welders and 111 297 referents). The crude and adjusted HR were 1.07 (95% CI 0.95–1.21) and 1.10 (95% CI 0.93–1.30), respectively. The unadjusted HR for cataract diagnosis and/or operation per ten years of welding was 1.18 (95% CI 1.11–1.25), but this effect disappeared when the model included age, diabetes, and social group [HR 1.04 (95% CI 0.98–1.09)].

Table 3

Risk of cataract in welders compared to a reference group of skilled and unskilled workers. [HR=hazard ratio.]

| N | Person-years at risk | Cataract a | % | Incidence rate | HRcrude | 95% CI | HRadj | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Welders | 4288 | 98 065 | 266 | 6.2 | 2.7/1000 years | 1.07 | 0.95–1.21 | 1.08 | 0.95–1.22 |

| Referents | 512 151 | 11 537 225 | 29 007 | 5.7 | 2.5/1000 years | 1.00 | .. | 1.00 | .. |

The risk of cataract was higher among men with diabetes [HR 1.73 (95% CI 1.7–1.8)] and the risk increased by age [HR 3.2 (95% CI 3.1–3.2) per 10 years increase in age]. Being a skilled worker protected against cataract [HR 0.93 (95% CI 0.91–0.96)].

Discussion

In this large study of metal arc welders, we did not find an elevated risk for being diagnosed or operated for cataract during a 25 years follow-up period. Strengths of this study include the prospective cohort design with a clearly defined group of welders, a large reference group, a long follow-up period of up to 25 years, and a well-defined registry-based outcome with either a hospital diagnosis or operation for cataract.

The study also has some limitations. Welders in the reference group could not be identified and this non-differential misclassification of exposure might cause bias towards null. However, welders constitute <5% of the entire population of male skilled and unskilled workers in Denmark (32, 33). Therefore exposure misclassification due to presence of welders in the reference population is considered of marginal importance.

Cataract diagnoses and operations are performed in both private and public hospitals. Until 2002, most operations were performed in public hospitals, and the records of the NPR are believed to be nearly complete. After 2002, private hospitals performed many of the operations, and studies have shown that reporting to the NPR has been incomplete (31). Welders and referents have equal and public paid access to the private hospitals if the waiting lists become sufficiently long at the public hospitals. There is no reason to believe that welders would visit private clinics more or less than the reference group with a similar socioeconomic position, so the missing data is expected to represent the same fraction for both groups. Registers are generally of high standard in Denmark, but changing variables from year to year and missing data due to lack of reporting from, eg, hospitals are well known limitations in register based studies.

A review from 2014 of 25 epidemiological studies about cataract and sunlight strongly supports that UV-B radiation is a risk factor for developing cortical cataract. UV-B has also been suggested as a risk factor for nuclear and posterior sub capsular cataract (PSC), but a positive association has not been shown in larger epidemiologic studies (17). In our study, it was not possible to differentiate between the different kinds of cataract which in a French study had the following distribution: cortical (12%), nuclear (22%), PSC (28%), mixed (20%) and unknown (18%) (21).

One study found that 76% of the welders have had photokeratoconjunctivitis during their work life, which indicates that acute high exposure of the eyes to UV-B or UV-C among welders does occur (6). However, no studies have reported data on how much UVR welders’ eyes are exposed to during a working day. Thus, we do not know whether welders are more or less exposed to UVR than outdoor workers. This study found that welders do not have an increased risk of cataract. Based on this, it is inferred that welders are not exposed to large amounts of UVR during their work life, in spite of the photokeratoconjunctivitis incidents.

Ophthalmologists have different criteria for diagnosing cataract and determining when a cataract operation is required. In the 1970s and 80s, the criteria for operation were different from today’s criteria, and cataract was supposed to “hyper mature” before an operation was performed. The threshold for operation has changed through the years and today an operation is offered at earlier stages of cataract. This effect is similar for both welders and referents and should not influence the results.

The questionnaire information on being a welder is highly reliable because exposure status was checked by company visits and rosters of employees when the cohort was created in 1985 (27). The welding work after 1985 is not estimated in this study. The lack of information on welding after 1985 causes misclassification of exposure, which most likely may bias the risk estimate toward null. However, a sensitivity analysis only including welders and referents aged >50 years at baseline revealed similar risk estimates. This is an indication that information bias is not an important issue.

It is not possible to adjust our data for all potential confounding factors because of lacking information. Diabetes is common after 60 years of age, and previous studies of the prevalence in Denmark have shown that using NPR register data identifies approximately 65% of all patients with diabetes (34–36). Persons with dysregulated diabetes and diabetes with multiple complications come into contact more often with hospitals and will also have a greater cataract risk. However, we found the same percentage of welders and referents with hospital-diagnosed diabetes.

Of the welders, 80.2% were smokers in 1985. This is a higher percentage than found in Denmark in 1987 for the lower socioeconomic group, where only in average 60–64% was active smokers (37). Smoking has since decreased in all social groups, and, in 2005, 29–49% of the lower social groups were smokers. If welders smoke more often than the referents and if smoking is causing cataract this would result in a falsely increased risk of cataract in welders – which was not observed (38).

Another potential confounding factor is the exposure to UVR from other sources, mostly the sun. Activities as working outdoor, sunbathing, use of sunglasses/hat, holidays etc, are unknown factors. Again, there is no reason to believe that welders would be exposed to these sources more or less than the reference group with similar socioeconomic position.

Our reference group had a higher percentage of unskilled workers (76.28% versus welders 47.90%). Higher socioeconomic status has been associated with decrease in cataract (15). However, the analyses were adjusted for social group, and confounding by social class seems unlikely.

It is not possible to take into account selection bias where workers with preexisting eye problems avoid welding, but our hospital record date back to 1977, and men diagnosed with eye disease between 1977 and the baseline in 1987 were excluded.