Work-related stress has shown to be a major risk factor for a range of adverse health outcomes, such as depression (1), coronary disease (2) and related mortality (3). The efficacy of interventions for occupational stress has been demonstrated in a large number of randomized controlled trials (4, 5). In spite of the availability of evidence-based interventions, the majority of stressed employees remain untreated. Using the internet to provide self-help interventions may help to overcome some of the limitations of traditional stress-management interventions (SMI) such as limited availability, high threshold for participation and delivery costs (6, 7). Internet-based interventions have been shown to be effective in clinical settings including the treatment of depression (8, 9, 10), anxiety (11), and risky alcohol use (12).

However, only a few interventions have been developed and evaluated to address the specific needs of the working population (13). A recent randomized trial found moderate effect sizes with regard to the reduction of depressive symptoms among stressed teachers (6, 14), whereas another trial did not find beneficial effects of a problem-solving training on depression or work-related outcomes (15, 16). So far, randomized controlled trials (RCT) on internet-based SMI show mixed results with some studies reporting significant results with moderate effects sizes on perceived stress (17–19) and others yielding non-significant outcomes (20, 21). Our group recently conducted a RCT testing the efficacy of an internet-based stress management intervention (iSMI) among employees with heightened levels of perceived stress (22, 23). The intervention proved to be effective in reducing perceived stress and other mental and work-related health outcomes. However, given the conflicting results for iSMI so far, replication is essential before a widespread dissemination can be considered. Furthermore, the aforementioned study evaluated an intervention that provided participants with substantial professional support (≤4 hours of guidance from a mental health expert for each participant). Although this requires significantly fewer resources than most individual CBT interventions, there might still be room for reducing this costly component even further. In the face of ample evidence that internet-based interventions (IBI) without guidance are less effective than guided interventions (24), and that unguided stress management interventions fail to show significant effects (25–27), it remains a challenging task to develop and disseminate iSMI that require only a minimum of guidance in order to produce a significant outcome.

One way to enhance the cost-efficacy of these interventions is to use the cost-intensive guidance component exclusively to foster adherence to the self-help intervention and not to provide detailed feedback on the exercises participants complete (28, 29). In such an adherence-focused guidance concept, participants are supported in the regular completion of the intervention sessions (ie, e-mail reminders); however, feedback is only provided upon request of the participant. This format may be promising in maintaining the positive effects of guidance whilst keeping the time spent per participant at a minimum; thus, producing a more economic version of iSMI. However, it has not been evaluated whether an iSMI using adherence-focused guidance can be effective.

Purpose of the present study

This study aims to strengthen the evidence base for internet- and mobile-based SMI by investigating the acceptability, effectiveness and mechanism of change of an adherence-focused guided iSMI among employees with heightened levels of perceived stress. We hypothesized the iSMI to be more effective in reducing perceived stress when compared to a waitlist control group (WLC). In secondary explorative analyses, we examined whether the iSMI and WLC groups would differ with regard to important work-related outcomes [work engagement, psychological detachment from work, emotional exhaustion, number of days with reduced productivity at work (presenteeism), number of days on sick leave (absenteeism)], the improvement of relevant skills (general distress- and specific emotion-regulation skills), mental health (depression, anxiety, insomnia, worrying) or quality of life concerning mental and physical health. We also hypothesized that initially achieved changes remain stable at a 6-month follow up and that changes in perceived stress from baseline to post-treatment would be mediated by changes in emotion regulation competencies regarding general distress.

Methods

Design

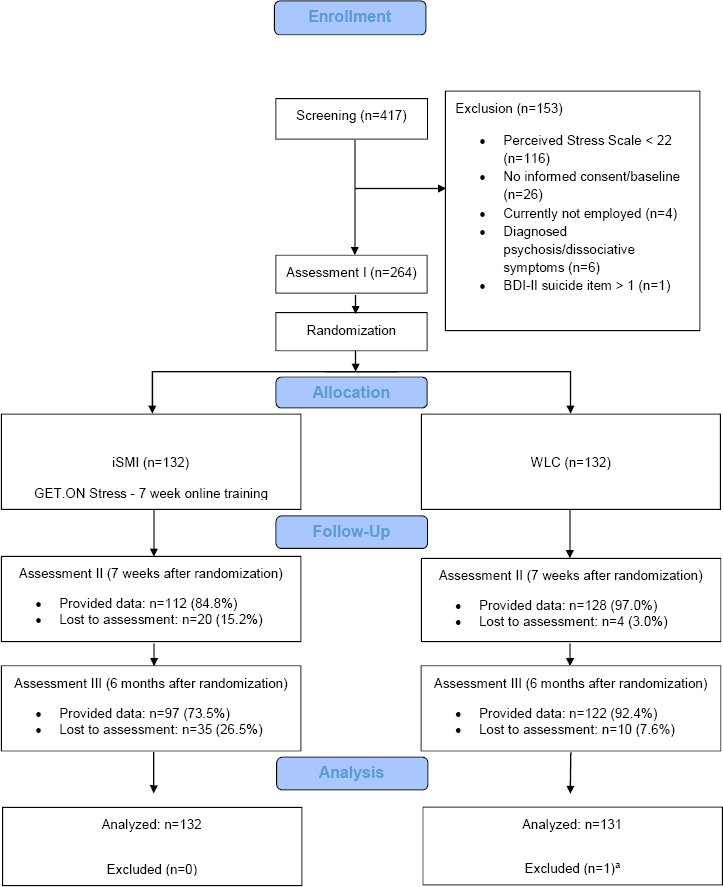

A two-armed RCT was conducted to compare adherence-focused guided iSMI (GET.ON Stress) with a WLC. Both conditions had full access to treatment-as-usual. Assessments took place at baseline (T1), post-treatment (7 weeks, T2), and 6-month follow-up (T3; see Figure 1 for a detailed overview of assessments; trial register: DRKS00005112).

Recruitment

Participants were primarily recruited via the occupational health program of a large health insurance company in Germany. Recruitment was directed at the general working population and not restricted to members of the healthcare insurance company. It occurred through announcements on the healthcare insurance company’s website, newspaper articles and advertisements in the membership magazine of the insurance company. Moreover, the insurance company’s occupational health management workers informed human resource departments of collaborating small- and medium-sized companies about the possibility for their employees to participate in the trial.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included (i) currently employed individuals, (ii) ≥18 years, (iii) with scores ≥22 on the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10), (iv) who had internet access, and (v) sufficient German skills in reading and writing (self-report). We excluded subjects who (a) reported to have been diagnosed with psychosis or dissociative symptoms in the past, (b) showed a notable suicidal risk as indicated by a score >1 on Becks Depression Inventory (BDI) item 9.

Assessment of eligibility and randomization

Individuals who contacted us via e-mail for study participation received an online information letter via e-mail with detailed information about the study procedures and were asked to complete an online screening questionnaire.

Individuals who met all of the inclusion criteria were invited to complete the informed consent form and the baseline assessment. Following this, they were randomly allocated to one of the two study conditions. Randomization took place at an individual level, using an automated computer-based random integer generator (randlist).

Study condition

Intervention condition

The IBI GET.ON Stress [for a detailed description see (22)] was based on Lazarus’ transactional model of stress (30). Problem-focused coping is used to actively influence a stress situation in a positive way through the use of cognitive or behavioral efforts. Emotion regulation refers to a variety of processes whereby individuals attempt to control and manage the spontaneous flow of their emotions to accomplish their needs and goals. Emotion-focused coping primarily serves the function of managing difficult emotions such as anger, disappointment, frustration and sadness in relation to the specific situation. On the one hand, many problems employees often encounter can theoretically be solved. Problem solving is an evidence-based method for dealing with such problems that has been proven to be successful in improving mental health (31). On the other hand, employees are also frequently faced with situations that require dealing with unsolvable problems; such situations are often associated with strong negative affective reactions and require effective regulation strategies. Numerous studies indicate that deficits in emotion regulation may be a relevant factor for the development and persistence of mental health symptoms (32, 33). Emotion regulation skills have been shown to be promising for reducing a broad range of such symptoms (34). While problem-focused coping by means of problem-solving techniques is a well-established component of most cognitive behavorial therapy (CBT) stress management trainings, the emotion-focused ways of coping could be regarded as the forgotten component. Only recently, emotion regulation gained more attention and elaborated concepts were developed. The intervention consisted of eight modules (see table 1 for an overview). Each session could be completed in approximately 45–60 minutes. If desired, the participants received automatic motivational text messages and exercises on their mobile phones. These messages aimed at supporting the participants in transferring the training exercises into their daily lives (eg, short relaxation exercises: “Relax your muscles in your hands and arms for 3 seconds now. Follow your breathing and each time you breathe out, relax a little more.”). Participants were supported by an e-coach applying an adherence-focused guidance concept. For a detailed description see (28). The purpose of the guidance was to support participants to adhere to the treatment modules whilst keeping it to a minimum in order to minimize costs. In line with the supportive accountability model (35), it is assumed that adherence to an IBI (and therefore the effectiveness) can be enhanced via human support through accountability to a coach who is seen as legitimate, trustworthy, benevolent, and having expertise. The e-coach guidance consisted of two elements: (a) adherence monitoring and (b) feedback on demand. Adherence monitoring included offering participants support in adhering to the intervention by regularly checking whether participants have completed intervention sessions on time, and if not, to remind them to do so. The e-coaches sent reminders in the event that participants had not completed at least one session within seven days. Both personal and automatic reminders have shown to improve adherence to self-guided health promotion and behavior change interventions (36, 37), but it is assumed that personal as opposed to automatic reminders from a coach are perceived as more benevolent and more effective. According to the model, it is made clear to the participant that the aim of adherence monitoring is to provide feedback and that feedback in turn provides opportunities for self-reflection, thus aiming to help to achieve personal goals rather than exposing or punishing the participant. Feedback on demand provided the participants with the opportunity to contact the coach via the internal messaging system of the platform and to receive individual support/feedback whenever such a need may arise. Within 48 hours, the participants received personalized written feedback. Feedback is not assumed to have a direct influence on the effectiveness of the intervention. Instead, it aims at creating perceived legitimacy of the coach and a sense that the coach has the participant’s best interest at heart. Individuals are assumed to respond more positively to adherence demands from a coach who is perceived as legitimate (35, 38). Hence, perceived legitimacy of the coach is believed to further increase adherence and constitute a necessary precondition for adherence monitoring to have a positive effect. In total, the e-coaches sent 463 reminders which corresponded to a mean of 3.51 reminders per participant [range: 0–13, standard deviation (SD) 1.98]. Interestingly, only few participants (N=3, 2.27%) requested feedback, resulting in only 8 content feedbacks for the entire sample. This corresponds to an average of 0.06 feedback demands per participant (range: 0–5, SD=0.46). Thus, most time spend per participant was related to check the adherence and to provide reminders.

Table 1

Content of the training GET.ON Stress.

| Session | Intervention content | Optional modules a |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Psycho-education | n/a |

| 2 | Problem-solving I (learning phase) |

Choice of one additional topic in each of the modules 2–6: • time management • rumination and worrying • psychological detachment from work • sleep hygiene • rhythm and regularity of sleeping habits • nutrition and exercise • organization of breaks during work • social support. |

| 3 | Problem-solving II (maintenance phase) | |

| 4 | Emotion regulation I (muscle- and breathing relaxation) | |

| 5 | Emotion regulation II (acceptance and tolerance of emotions) | |

| 6 | Emotion regulation III (effective self-support in difficult situations) | |

| 7 | Plan for the future | n/a |

| 8 | Booster session (4 weeks after completion of the training) | n/a |

Primary outcome measure

Perceived stress

The primary outcome was level of perceived stress as measured by the PSS-10, (39). Cronbach’s α was 0.88 at T2 and 0.90 at T3 in this study. The items were answered on a 5-point Likert scale (0=never; 1=almost never; 2=sometimes; 3=fairly often; 4=very often). Accordingly, the sum score ranges from 0–40.

Secondary outcome measures

In secondary analyses, the effect of the below-mentioned outcomes between iSMI and WLC group is reported. The number of items, range of items and reliabilities found at T2 in this study are shown in parentheses. Secondary outcomes included the following:

Mental health:

depression (Center for Epidemiological Studies’ Depression Scale, CES-D, (40); 20 items; range 0–60; α=0.89), anxiety (anxiety subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scales, HADS-A, (41); 7 items; range 0–21; α=0.79); insomnia severity (Insomnia Severity Index, ISI, (42); 7 items; range 0–28; α=0.87), worrying (Penn State Worry Questionnaire-Ultra Brief Version-past week, PSWQ-PW, (43); 3 items; range 0–18; α=0.85).

Work-related outcomes

emotional exhaustion (subscale emotional exhaustion of the Maslach Burnout Inventory, MBI- EE, (44); 5 items; range 1–6; α=0.89), work engagement (Utrecht Work Engagement Scale, UWES, (45); 9 items; range 0–6; α=0.95), psychological detachment from work (subscale of the Recovery Experience Questionnaire, REQ-PD, (46); 4 items; range 1–5; α=0.92). To assess the number of “work loss” days (absenteeism from work) and the number of “work cut-back” days (reduced efficiency at work while feeling ill; presenteeism) we used the respective items of the German Version of the Trimbos and Institute of Medical Technology Assessment Cost Questionnaire for Psychiatry (TiC–P-G) (47).

Skills/competencies

To assess emotion regulation skills we used the subscales comprehension, acceptance, and emotional self-support of the ERSQ-27 [-C,-A,-SS (48, 49); 9 items, range 0–4; α=0.85, 0.88, 0.89] and the subscale regarding emotion regulation skills for general distress of the German Emotion Regulation Skills Questionnaire (using the Emotion Specific Version, ERSQ-ES-GD, (49); 12 items, range 0–4; α=0.88).

Additional measurements

Additional questionnaires included demographic variables and client satisfaction [German version of the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire, adapted to the online context, CSQ-8; (50) 8 items].

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed with SPSS version 22 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). A significance level of 0.05 (two-sided) was used for all outcome variables. Multiple imputation was used to handle missing data (51).

Differences in change in the outcomes between iSMI and WLC groups over time were assessed using repeated measures ANOVAs with time (T1, T2, T3) as a within-subject factor. If the overall effect became significant, we continued with investigating individual differences in change from T1 to T2, and from T1 to T3. Thereby, we report the corrected F-values according to the conservative Greenhouse–Geisser adjustment method. Cohen’s d with its 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) was calculated as a measure of the size of the effect.

Response

To determine the number of participants achieving a reliable positive outcome we coded participants as responders or non-responders according to the widely used Reliable Change Index (RCI) (PSS-10 change > -5.16) (52). Additionally, the number needed to treat (NNT) was calculated. To determine potential negative effects of the intervention (53, 54) we also assessed the number of participants with reliable symptom deterioration according to the RCI.

Symptom-free status

A cut-off point indicating symptom-free status was calculated. This was defined as scoring >2 SD below the mean (T1) of the stressed population (Mean 25.26, SD 4.37); ie, in this study by having a score of ≤16.52 on the PSS-10 at the post-assessment and at the 6-month follow-up, respectively.

Maintenance of gains

Stability of the effects were concluded when (i) the 95% CI of the between-group effect size at post-treatment and 6-month follow-up effect overlapped and (ii) the decline in the effect size from post-treatment to follow-up was not greater than d= -0.10.

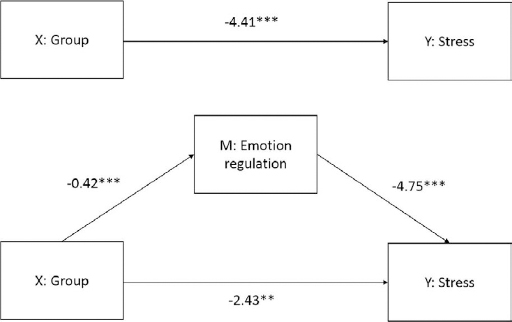

Mediator analysis

Emotion regulation competencies were tested as one core assumed mechanism of change of this multi-component intervention using a mediator model with age and sex as covariates. We hypothesized that the intervention effect on the primary outcome – change in perceived stress – is mediated by a change in stress-specific emotion regulation competencies. We used the PROCESS macro for SPSS (version 2.13.1) with bias-corrected bootstrapping (1000) to obtain 95% CI for testing the indirect effect. An indirect effect was considered significant if the 95% CI for the coefficient estimate did not include zero.

Results

Participants

The enrollment and flow of participants throughout the study is summarized in Figure 1.

Baseline characteristics

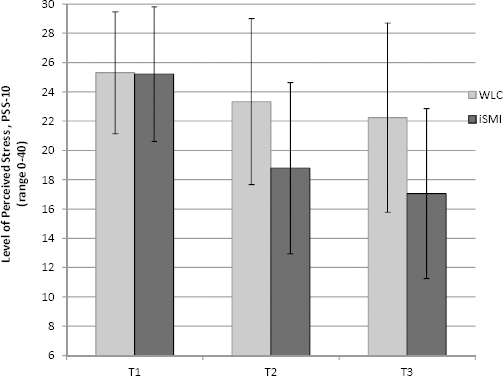

Table 2 presents detailed baseline characteristics of the study participants. Interestingly, a total of 153 (58.2%) were first-time-helper-seeker (ie, never took part in a mental health promotion training or psychotherapy). Table 3 shows descriptive data for all outcome variables at all assessment points. Figure 2 displays a graph of the level of perceived stress at each assessment point for both groups.

Table 2

Baseline characteristics. [iSMI=internet-based stress management intervention; WLC=waitlist control group; SD=standard deviation; IT=information technology].

| Characteristics | All participants (N=263) | iSMI (N=132) | WLC (N=131) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

| N | % | Mean | SD | N | % | Mean | SD | N | % | Mean | SD | ||||

| Socio-demographics | |||||||||||||||

| Age, years | · | · | 42.9 a | 9.8 | · | · | 42.6 | 9.4 | · | · | 43.2 b | 10.2 | |||

| Gender, female | 226 | 85.9 | · | · | 113 | 85.6 | · | · | 113 | 86.3 | · | · | |||

| Married/in a relationship | 149 | 56.7 | · | · | 80 | 60.6 | · | · | 69 | 52.7 | · | · | |||

| Ethnicity | |||||||||||||||

| Caucasian/white | 217 | 82.5 | · | · | 108 | 81.8 | · | · | 109 | 83.2 | · | · | |||

| Asian | 2 | 0.8 | · | · | 1 | 0.8 | · | · | 1 | 0.8 | · | · | |||

| Prefer not to say | 44 | 16.7 | · | · | 23 | 17.4 | · | · | 21 | 16.0 | · | · | |||

| Educational level | |||||||||||||||

| Low | 5 | 1.9 | · | · | 2 | 1.5 | · | · | 3 | 2.3 | · | · | |||

| Middle | 69 | 26.2 | · | · | 36 | 27.3 | · | · | 33 | 25.2 | · | · | |||

| High | 189 | 71.9 | · | · | 94 | 71.2 | · | · | 95 | 72.5 | · | · | |||

| Working characteristics | |||||||||||||||

| Full-time | 200 | 76.0 | · | · | 103 | 78.0 | · | · | 97 | 74.0 | · | · | |||

| Part-time | 61 | 23.1 | · | · | 28 | 21.2 | · | · | 33 | 25.2 | · | · | |||

| On sick leave | 2 | 0.8 | · | · | 1 | 0.8 | · | · | 1 | 0.8 | · | · | |||

| Work experience in years | · | · | 18.0 | 10.9 | · | · | 18.1 | 10.6 | · | · | 18.0 | 11.2 | |||

| Working sectors | |||||||||||||||

| Social | 64 | 24.3 | · | · | 28 | 21.2 | · | · | 36 | 27.5 | · | · | |||

| Service | 63 | 24.0 | · | · | 30 | 22.7 | · | · | 33 | 25.2 | · | · | |||

| Economy | 43 | 16.3 | · | · | 27 | 20.5 | · | · | 16 | 12.2 | · | · | |||

| Health | 38 | 14.4 | · | · | 23 | 17.4 | · | · | 15 | 11.5 | · | · | |||

| IT | 11 | 4.2 | · | · | 7 | 5.3 | · | · | 4 | 3.1 | · | · | |||

| Others | 44 | 16.7 | · | · | 17 | 12.9 | · | · | 27 | 20.6 | · | · | |||

| Income in euros/year | |||||||||||||||

| <10 000 | 10 | 3.8 | · | · | 4 | 3.0 | · | · | 6 | 4.6 | · | · | |||

| 10 000–30 000 | 68 | 25.9 | · | · | 37 | 28.0 | · | · | 31 | 23.7 | · | · | |||

| 30 000–40 000 | 65 | 24.7 | · | · | 33 | 25.0 | · | · | 32 | 24.4 | · | · | |||

| 40 000–50 000 | 47 | 17.9 | · | · | 21 | 15.9 | · | · | 26 | 19.8 | · | · | |||

| 50 000–60 000 | 28 | 10.6 | · | · | 19 | 14.4 | · | · | 9 | 6.9 | · | · | |||

| 60 000–100 000 | 15 | 5.7 | · | · | 6 | 4.5 | · | · | 9 | 6.9 | · | · | |||

| >100 000 | 6 | 2.3 | · | · | 3 | 2.3 | · | · | 3 | 2.3 | · | · | |||

| Prefer not to say | 24 | 9.1 | · | · | 9 | 6.8 | · | · | 15 | 11.5 | · | · | |||

| Experience | |||||||||||||||

| Previous health training | 37 | 14.1 | · | · | 17 | 12.9 | · | · | 20 | 15.3 | · | · | |||

| Previous psychotherapy | 77 | 29.3 | · | · | 36 | 27.3 | · | · | 41 | 31.3 | · | · | |||

| Current psychotherapy | 21 | 8.0 | · | · | 10 | 7.6 | · | · | 11 | 8.4 | · | · | |||

| First-time help seeker | 153 | 58.2 | · | · | 79 | 59.8 | · | · | 74 | 56.5 | · | · | |||

Table 3

Means and standard deviations (SD) for the internet-based stress management intervention (iSMI) and waitlist control group (WLC) (intention-to-treat sample) at pre- (T1), post-treatment (T2) and 6-month follow-up (T3).

| Outcome | T1 | T2a | T3a | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| iSMI | WLC | iSMI | WLC | iSMI | WLC | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Primary outcome | ||||||||||||

| Perceived stress (low to high 0–40) b | 25.21 | 4.59 | 25.31 | 4.16 | 18.79 | 5.85 | 23.33 | 5.66 | 17.05 | 5.81 | 22.24 | 6.46 |

| Mental health (low to high scores) | ||||||||||||

| Depression (0–60) c | 23.17 | 9.27 | 24.27 | 8.39 | 17.69 | 8.21 | 22.46 | 9.17 | 15.52 | 7.05 | 22.75 | 9.78 |

| Insomnia (0–28) d | 13.21 | 5.72 | 13.20 | 5.88 | 9.05 | 5.16 | 11.88 | 5.65 | 8.90 | 5.17 | 11.97 | 6.04 |

| Anxiety (0–21) e | 10.65 | 3.35 | 11.12 | 3.25 | 7.67 | 3.37 | 10.38 | 3.45 | 6.86 | 3.28 | 10.04 | 3.92 |

| Worrying (0–18) f | 10.05 | 4.00 | 10.58 | 3.56 | 7.35 | 4.00 | 9.58 | 3.67 | 6.47 | 3.47 | 9.06 | 4.34 |

| Quality of life (physical health) g, h | 46.82 | 8.75 | 47.15 | 9.12 | · | · | · | · | 48.21 | 8.09 | 47.61 | 8.39 |

| Quality of life (mental health) g, i | 35.38 | 8.84 | 34.54 | 9.28 | · | · | · | · | 44.64 | 8.40 | 37.17 | 10.61 |

| Work-related health (low to high scores) | ||||||||||||

| Emotional exhaustion (1–6) j | 4.73 | 0.77 | 4.73 | 0.75 | 4.03 | 0.89 | 4.65 | 0.79 | 3.73 | 0.94 | 4.48 | 0.91 |

| Work engagement (0–6) g, k | 3.22 | 1.36 | 3.11 | 1.25 | 3.26 | 1.34 | 3.08 | 1.32 | 3.41 | 1.24 | 3.21 | 1.30 |

| Psychological detachment (1–5)g, l | 2.37 | 0.85 | 2.34 | 0.87 | 2.81 | 0.93 | 2.48 | 0.94 | 2.93 | 0.95 | 2.51 | 0.95 |

| Absenteeism (days)m, n | 4.87 | 11.04 | 3.59 | 8.83 | · | · | · | · | 7.37 | 14.71 | 5.17 | 10.52 |

| Presenteeism (days) m, o | 15.58 | 14.92 | 14.64 | 14.12 | · | · | · | · | 10.31 | 9.85 | 12.02 | 11.93 |

| Emotion regulation skills/competencies (low to high 0–4) g, p | ||||||||||||

| Comprehension | 2.52 | 0.91 | 2.39 | 0.91 | 3.00 | 0.68 | 2.56 | 0.91 | 3.10 | 0.66 | 2.71 | 0.83 |

| Acceptance | 2.11 | 0.97 | 1.94 | 0.85 | 2.67 | 0.78 | 2.16 | 0.94 | 2.83 | 0.72 | 2.28 | 0.90 |

| Self-support | 2.20 | 0.92 | 2.09 | 0.84 | 2.66 | 0.78 | 2.25 | 0.94 | 2.76 | 0.79 | 2.35 | 0.85 |

| General distress q | 1.88 | 0.60 | 1.84 | 0.54 | 2.40 | 0.57 | 1.94 | 0.62 | 2.42 | 0.57 | 2.01 | 0.65 |

Figure 2

Levels of perceived stress according to the Perceived Stress 10-item Scale (PSS-10) for the internet-based stress management intervention (iSMI) and waitlist control group (WLC) at all assessment points for the intention-to-treat (ITT) sample at pre-test (T1), post-test (T2), 6 months (T3).

Adherence to the intervention & client satisfaction

Session 1 was completed by 125 (94.7%), session 2 by 119 (90.2%), session 3 by 111 (84.1%), session 4 by 101 (76.5%), session 5 by 97 (73.5%), session 6 by 92 (69.7%), session 7 by 91 (68.9%) and session 8 by 65 (49.2%) of the participants. On average, participants of the iSMI group completed 5.58 modules (SD 2.33) which equals to 79.7% of the intervention and worked 6.55 weeks (SD 5.41; range 0–33) on the intervention. In the majority of the sessions (85.5%) in which an elective module was available, participants completed an optional module. With regard to the completion of specific optional modules, 45.5% (N=60) of the participants completed rumination and worrying, 43.2% (N=57) psychological detachment from work, 37.1% (N=49) nutrition and exercise, 34.8% (N=46) time management, 31.1% (N=41) sleep hygiene, 21.2% (N=28) sleep restriction and stimulus control, 22.0% (N=29) organization of breaks during work, and 21.2% (N=28) chose social support. Overall client satisfaction was very high (see table 4).

Table 4

Client’s rating of their satisfaction with intervention.a

Primary outcome analyses

Changes in perceived stress

As hypothesized, the repeated measures ANOVA for the primary outcome revealed a highly significant overall effect (F1.99,520.05=25.22, P<0.001; see table 5). In the following separate ANOVA, the iSMI group showed lower scores on the primary outcome PSS-10 at post-test (T2; F1,261=33.09, P<0.001) and at the 6-month follow-up (T3; F1,261=40.19, P<0.001) as compared to the WLC. Large effect sizes of Cohen’s d were observed at post-test (d=0.79; 95% CI 0.54–1.04) and the 6-month follow-up d=0.85; 95% CI 0.59–1.10).

Table 5

Results of the repeated measures analysis of variances (ANOVA) and Cohen’s d for the primary and secondary outcome measures (ITT sample) at post-test and 6 months follow-up (between group effects). [95% CI=95% confidence interval.]

| Outcome | ANOVA a,b overall effect | ANOVA T1–T2 | T2 a Between-groups effect | ANOVA T1–T3 | T3 a Between-groups effect | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| F | df | P | F(1,261) | P | Cohen’s d | 95% CI | F(1,261) | P | Cohen’s d | 95% CI | |

| Primary outcome | |||||||||||

| Perceived stress c | 25.22 | 1.99, 520.05 | <0.001 | 33.09 | <0.001 | 0.79 | 0.54–1.04 | 40.19 | <0.001 | 0.85 | 0.59–1.10 |

| Mental health | |||||||||||

| Depression d | 18.60 | 1.87, 486.88 | <0.001 | 13.54 | <0.001 | 0.55 | 0.30–0.79 | 29.46 | <0.001 | 0.85 | 0.60–1.10 |

| Insomnia e | 16.39 | 1.87, 488.49 | <0.001 | 24.03 | <0.001 | 0.52 | 0.28–0.77 | 21.16 | <0.001 | 0.55 | 0.30–0.79 |

| Anxiety f | 29.77 | 1.90, 495.28 | <0.001 | 41.47 | <0.001 | 0.79 | 0.54–1.04 | 42.42 | <0.001 | 0.88 | 0.63–1.13 |

| Worrying g | 9.91 | 1.99, 518.22 | <0.001 | 12.16 | <0.01 | 0.58 | 0.33–0.83 | 16.03 | <0.001 | 0.66 | 0.41–0.91 |

| Quality of life (physical health) h | · | ·· | · | · | · | · | ·· | 0.95 | 0.332 | 0.07 | -0.17–0.31 |

| Quality of life (mental health) i | · | ·· | · | · | · | · | ·· | 29.14 | <0.001 | 0.78 | 0.53–1.03 |

| Work-related health | |||||||||||

| Emotional exhaustion j | 30.00 | 1.87, 486.96 | <0.001 | 48.17 | <0.001 | 0.73 | 0.48–0.98 | 44.13 | <0.001 | 0.81 | 0.56–1.06 |

| Work engagement k | 0.27 | 1.96, 511.62 | 0.761 | 0.30 | 0.584 | 0.14 | -0.11–0.38 | 0.44 | 0.508 | 0.15 | -0.09–0.40 |

| Psychological detachment l | 7.96 | 1.94, 507.46 | <0.001 | 9.77 | <0.01 | 0.34 | 0.10–0.59 | 13.32 | <0.001 | 0.44 | 0.20–0.69 |

| Absenteeism m | . | .. | . | . | · | · | ·· | 0.22 | 0.641 | -0.17 | -0.41–0.07 |

| Presenteeism n | . | .. | . | . | . | . | .. | 1.90 | 0.169 | 0.16 | -0.09–0.40 |

| Skills/Competencies regarding emotion regulation o | |||||||||||

| Comprehension | 5.85 | 1.89, 493.85 | <0.01 | 9.89 | <0.01 | 0.55 | 0.30–0.80 | 6.07 | <0.05 | 0.52 | 0.28–0.77 |

| Acceptance | 8.41 | 1.90, 496.10 | <0.001 | 10.87 | <0.01 | 0.59 | 0.34–0.84 | 11.80 | <0.01 | 0.68 | 0.43–0.93 |

| Self-support | 5.06 | 1.81, 472.30 | <0.01 | 7.61 | <0.01 | 0.47 | 0.23–0.72 | 5.99 | <0.05 | 0.50 | 0.26–0.75 |

| General distress p | 19.69 | 1.90, 495.88 | <0.001 | 36.34 | <0.001 | 0.78 | 0.53–1.03 | 21.00 | <0.001 | 0.68 | 0.43–0.92 |

Treatment response

Significantly more participants of the iSMI group were classified as responders N=72 (54.5%) compared with the WLC at post-test (N=31, 23.7%; Chi2=26.32; P<0.001; NNT=3.24, 95% CI 2.38–5.08) and the 6-month follow-up, (iSMI: N=85; 64.4%; WLC: N=49; 37.4%; WLC; Chi2=19.16; P<0.001; NNT=3.71, 95% CI 2.59–6.51).

Symptom-free status

Symptom-free status was shown by significantly more participants of the iSMI group (N=47;35.6%) as compared to the WLC (N=13; 9.9%; Chi2=24.63, P<0.001, NNT=3.89, 95% CI 2.83–6.23) at post-treatment and 6-month follow-up, (iSMI: N=61; 46.2%, WLC: N=24; 18.3%; Chi2=23.38, P<0.001; NNT=3.59, 95% CI 2.59–5.84).

Symptom deterioration

Only few participants experienced symptom deterioration during the trial period. The number of participants did not significantly differ between the groups at post-treatment (iSMI: N=5, 3.8%; WLC: N=9, 6.9%; P=0.266), but rather at 6-month follow-up (iSMI: N=3, 2.3%; WLC: N=13, 9.9%; Chi2=6.74; P<0.01).

Secondary outcome analysis

Table 5 presents the results of the intention-to-treat analyses for the secondary outcomes. The repeated measures ANOVA revealed significant effects (all P<0.01) in favor of the intervention group for all outcomes that were assessed both at T2 and T3 apart from work engagement (P=0.761). In the following analyses of the simple effects, the ANOVA showed significant effects for all outcomes at both assessment points (all P<0.05), except for quality of life concerning physical health, absenteeism and presenteeism.

Mechanism of change

Results for each of the partial chains within the mediator model are presented in Figure 3. As hypothesized, there was a significant indirect effect (β= -1.98, SE=0.41, 95% CI -2.82– -1.20) of emotion regulation on the reduction in perceived stress. The direct effect of the intervention on the reduction of perceived stress remained significant even after the inclusion of emotion regulation as mediator in the model (β= -2.43, SE=0.74, 95% CI -3.89– -0.97). This indicates evidence for a partial mediation.

Discussion

Results of the present study confirm the primary hypothesis that the intervention effectively reduces symptoms of perceived stress. Secondary explorative analyses indicate beneficial effects also on a range of relevant mental-health-related (ie, depression, anxiety, worrying, insomnia severity, mental health component of quality of life), work-related health (ie, emotional exhaustion, psychological detachment from work) and skill-related (ie, general emotion regulation skills, emotion specific emotional regulation skill for general distress) outcomes. No significant effects were found for absenteeism, presenteeism, work engagement and the physical component of quality of life. A mediator analysis showed that changes in emotion regulation with regard to general distress partially mediated the effect of the intervention on perceived stress.

The effects found in the present study were larger than those found for iSMI in previous trials using other interventions. These trials yielded mixed results, ranging from non-significant for a web-based psychoeducational intervention in the general working population (21), small-to-moderate for a smartphone-based acceptance and commitment intervention for middle managers (55), to moderate effect sizes for a viable mind-body stress reduction intervention (56). Moreover, our results are comparable to post-treatment results found for face-to-face occupational stress management interventions in the latest meta-analysis on this topic (d=0.73 for stress-reduction, d=0.68 for anxiety, d=0.44 for mental health such as depression) (4), but are slightly lower for stress reduction than mean results for CBT-based interventions in this meta-analysis (d=1.15, for stress-reduction, d=0.71 for mental health such as depression), although the 95% CI for the effect sizes in the present study overlap with those of effects found in that meta-analysis. Comparing long-term effects of the present intervention to meta-analytic findings for face-to-face interventions is not possible as the most recent meta-analysis on this topic was not able to examine those due to a lack of sufficient number of studies assessing a long-term follow up (>6 months). Thus, the present study provides further evidence that CBT-based interventions can have enduring effects that go beyond immediate short-term effects, and can also prevent further aggravation of symptoms. Remarkably, the effect sizes for most outcomes were similar to those found in the pilot-evaluation study of the novel intervention (23). Thus, the present study replicated the results of this study in a large-scale randomized controlled trial. Moreover, whilst in the pilot evaluation the intervention was delivered with substantial human support from a psychologist (approximately four hours per participant), the present study found also clinically meaningful effects without providing regular written feedback on each session. Instead of providing detailed feedback on the weekly exercises the participants had completed, the e-coach only monitored the adherence to the intervention and provided feedback on the content only on request of the participants. Surprisingly, few participants demanded content feedback (across all 132 participants, only 8 content feedbacks were provided which corresponds to an average of 0.06 feedbacks per participant). The maximum time spent per participant was approximately one hour, and most of the resources spent for coaching were necessary to monitor the adherence to the intervention. With regard to the cost-effectiveness of the intervention this finding is promising. Although four hours of coaching per participant (23) is already much less than an individual face-to-face CBT intervention, even more employees could get access to interventions for the same costs if meaningful results can be also achieved in a less intensive guidance format. The large effects found in the present study are in line with the assumption that the responsible factor for the higher effect sizes which are frequently found for guided versus unguided self-help interventions (15, 57, 58) is attributable to the adherence-promoting factor of human support. This has also been stated previously in the supportive accountability model of human support in IBI (35). However, RCT that compare adherence-focused guidance format with regular content feedbacks are needed to support such an assumption and to determine whether or not adherence-focused guidance formats can result in equivalent outcomes as more intensive content-focused guidance formats. However, even if a less intensive guidance format should yield lower effects in direct comparisons, their potential on a population level might still be higher as such interventions have a greater reach and more participants can be treated for the same costs (28, 59). On the other hand, it may very well be the case that employees are less willing to participate in an intervention if no regular content feedback is provided, which would result in lower overall effects in the target population (60, 61). Thus, future studies should compare the acceptability, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of different guidance formats for iSMI (19, 62).

Relevant work-related health outcomes, such as emotional exhaustion and psychological detachment from work, improved significantly. However, no significant effects were found for the number of days of absenteeism and presenteeism, respectively. These findings suggest that even a substantial improvement in mental health does not automatically lead to a reduction in absenteeism and presenteeism. This finding is in line with findings for face-to-face CBT interventions for occupational stress (63). Adding optional modules on coping with sick leave or working whilst being sick might be beneficial, especially for participants seeking help in these matters.

This study has the following limitations. First, the present trial applied an open recruitment strategy, meaning that participants were actively recruited from the general working population and the intervention was delivered from an external institution (the university). We cannot rule out a potential selection bias and it may be possible that employees are less willing to utilize such an intervention and/or may react differently to it if it is delivered, for example, from an occupational health department within a company. Future studies are therefore needed that evaluate iSMI applying different recruitment strategies. Third, although a mediator analysis indicated emotion regulation skills with regard to general distress to be one important mechanism of change, the design of the trial did not allow to test for causal mechanisms (64) as the mechanism and the outcome were assessed at the same measurement points. Future longitudinal studies with repeated assessments of putative mediators are clearly needed in order to confirm the finding and test other potential relevant mechanisms, ie, changes in self-efficacy. Fourth, several of the mental-health-related outcome measures were highly correlated and it might be the case that they actually measure a similar latent construct (eg, emotional exhaustion / depression). Fifth, due to feasibility reasons, we did not include any objective measurements. The study might have benefited from an inclusion of physiological measures and future studies could consider complementing self-reports with objective measurements (such as cortisol levels). Sixth, although the current study replicated the results of the pilot study on this newly developed intervention, future studies are needed to reliably estimate the potential effects of iSMI in different target populations, eg, among employees on sick leave.

In conclusion, the present study adds to the growing evidence that IBI have a high potential for delivering low-threshold evidence-based occupational health interventions. However, absenteeism and presentism were not affected and more research is clearly needed to investigate the potential of iSMI for these important work-related outcomes. Results of the present study also indicate that iSMI can be delivered with only limited human support involved without a substantial loss of effects; thus, potentially reaching a much greater population for the same costs than interventions with more intensive human support.