Common mental disorders (CMD) refer to two main diagnostic categories: depressive and anxiety disorders. Both disorders are diagnosable health conditions although symptoms range in terms of their severity (from mild to severe) and duration (from months to years). The number of persons with CMD is increasing globally. It was 416 million in 1990 and reached 615 million in 2013, including working-age population (1, 2). The cost of lost productivity in the workplace due to depression and anxiety is very high, approximately US$1 trillion per year (2). However, comparatively little is known about work-related risk factors that affect the risk of CMD.

Night work is an organizational arrangement needed to cope with modern civilization and tailored consumer demands. The proportion of night workers was reported to be 19% in the European Union in 2015 (3). Night work and shift work have been associated with various negative consequences for health and well-being, such as increased risk of cardiovascular disease, fatigue, reduction in the quantity and quality of sleep, anxiety, depression, exhaustion, gastrointestinal disorders, increased risk of miscarriage, low birth weight and premature birth, and cancer (3–5). Some studies suggest that a fixed night shift and shift work may be associated with greater risks of mental health problems (6) and other psychological and psychosocial symptoms (7–9). However, estimating this association accurately is challenging as CMD may affect the choice of continuing to work night shifts. To date this has not been taken into account in data analysis. Other limitations found in literature concerning this topic include small sample size, small periods of observation for the exposure and/or the outcome, and the reliance on self-report only to measure the outcome (9–20).

To address those limitations there is a need for more sophisticated epidemiological treatments and larger sample sizes to be implemented (21). In this study, we applied a novel approach to investigate night work and CMD. Using observational data with three waves of data collection enabled us to simulate a non-randomized pseudo trial to investigate potential causal association between night work as a risk factor for CMD (22). We created separate models to assess each of the following three hypotheses: (i) moving from non-night work to night work increases the risk of acquiring CMD, (ii) the odds of recovery from CMD is higher among night workers who move to non-night work compared to those who continue working night shifts, and (iii) among night workers, developing CMD increases the likelihood of moving to non-night work.

Methods

Overall study design

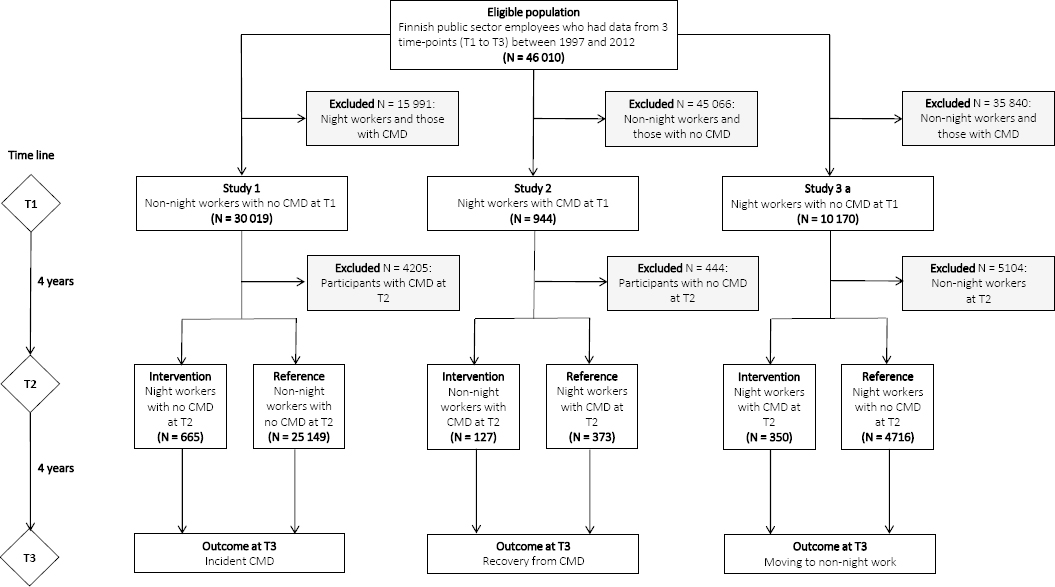

The pseudo trial consists of three models mimicking a quasi-experiment design. Study 1 examines the effect of moving from non-night to night work on subsequent risk of CMD. Study 2 examines the impact of moving from night to non-night work on the recovery from CMD. The aim of study 3 is to obtain a bias-corrected estimate for the effect examined in study 1. For this, we determined the extent to which developing CMD among night workers increases the likelihood of moving to non-night work, a source of selection bias. This information was then taken into account to re-estimate the effect of moving from non-night to night work on subsequent risk of CMD.

All three studies used data from the observational Finnish Public Sector study (FPS). FPS includes all employees from ten towns and six hospital districts in Finland and has collected repeat survey data at 4-year intervals from 1997−98 onwards on work-related, behavioral, physical and psychological health factors with response rates that have ranged from 66−71%. Assessment of CMD is register-based in the overall design.

FPS participants represent a wide range of occupations from semi-skilled cleaners to physicians and mayors (23). The base population includes 76 615 employees to whom a questionnaire was sent in 2−4 survey waves between 1997−2012 and who were linked to electronic health records. Of these, 46 010 participants working in social and healthcare sector who had responded to ≥2 surveys and had a 4-year follow-up for CMD after the second survey comprised the eligible population for the present pseudo trials (supplementary table S1, www.sjweh.fi/show_abstract.php?abstract_id=3733).

For a participant to be included in the first and second pseudo trial, we selected those who responded to at least one cycle covering three consecutive study waves (figure 1). A candidate was accepted in the pseudo trial if they responded to two consequent surveys (time 1 and time 2) and had linked data ≥4 years after the latter survey (time 3), a full data cycle. Adopting this design allowed us to have a 4-year window for the onset of exposure and a 4-year period to follow up the outcome. The analyses were conducted on pooled data from three cycles: (i) time 1=1997−1998, time 2=2000−2002 and time 3=2001/2003−2004, (ii) time 1=2000−2002, time 2=2004 and time 3=2005-2008; and (iii) time 1=2004, time 2=2008 and time 3=2009−2011/2012. Study 3 used a cohort of night workers at time 1 and time 2 with no CMD at time 1 and known status of night work at time 3 (figure 1).

Figure 1

Flow chart of cohort selection for pseudo trials examining the effect of moving from non-night work to night work on acquiring common mental disorders (CMD) (study 1), the effect of moving from night to non-night work on CMD remission (study 2), and the effect of acquiring CMD on choice of work schedule among night workers (study 3).

Participants

In study 1, we addressed the effect of working in night shifts on the development of CMD using a study design that simulates an experiment where the exposure is working in night shifts and the outcome is developing CMD. The quasi experiment started at time 1 with a population of 30 019 non-night workers with no CMD within four years before time 1. They were monitored for CMD via linked records over a 4-year period (from time 1 to time 2). Participants who developed CMD by time 2 (N=4205) were excluded. We then divided the participants who did not develop any CMD by time 2 (N=25 814) based on their work schedule into two groups, non-night (N=25 149) and night (N=665) workers. At this point, we were mimicking the effect of an intervention moving from non-night to night work and considering those who continued as non-night workers to be the reference group and those who moved to night shifts (night workers) as the intervention group. The two groups were then monitored for another 4-year period for incident CMD by time 3.

In study 2, we addressed the effect of the removal of a potential risk factor (working in night shifts) on recovery from CMD using a pseudo trial design that also simulates an experiment where the participants have a CMD and the treatment (ie, exposure) is a change from night to non-night work. Would this affect the status of their mental disorder? At time 1, the experiment started with a population of night workers with CMD (N=944). Of these, those who still suffer from CMD at time 2 continued in the experiment (N=500) while those who had recovered from such disorders were excluded (N=444). The continuing participants were divided at time 2 according to their work schedule into two groups, those who continued as night workers (the reference group, N= 373) and those who moved to non-night work (the intervention group, N=127). The two groups were then monitored for another 4-year period for prevalent CMD by time 3.

In study 3, we addressed the selection bias arising from reverse causation in the association between night work and risk of CMD, that is, that night workers who develop CMD may be more likely to return to non-night work than those who remain free of CMD. The study population included 10 170 night workers at time 1, no CMD at time 1 and no missing data on CMD and status of night work at time 2 and time 3. We examined whether those who developed CMD by time 2 were more likely to move back to non-night work by time 3 compared to those night workers who did not have CMD at time 2.

Assessment of night work

In all surveys, information on the working time model was requested by a single question with the following alternatives: (a) regular day time hours, (b) shift work, no night shifts (two shifts), (c) shift work, including night shifts, (d) regular night work, and (e) other form of irregular working hours. Those choosing options c and d were defined as night workers, while options a, b, and e were defined as non-night workers.

Assessment of common mental disorders

All FPS participants have been linked to national health registers. We used two sources to identify participants with CMD: (i) records of sickness absence due to mental disorders (24) from the Sickness Absence Register of the Social Insurance Institution of Finland (this is an electronic record of the beginning and ending dates of all periods of sickness absences with diagnosis); and (ii) antidepressant purchase (25) from the Drug Prescription Register which is an electronic pharmacy-claims database. CMD was defined as a composite of disorders indicated by sickness absence with an ICD-10 F00-F99 diagnosis (mental and behavioral disorders) or prescribed antidepressant treatment with ATC code N06A (25), or both. The ICD-10 F00-F99 category includes depressive episode, anxiety disorders, reaction to severe stress and adjustment disorders, nonorganic sleep disorder, neurotic disorders among other disorders represented in the study sample in small percentages (supplementary table S2, www.sjweh.fi/show_abstract.php?abstract_id=3733).

Both at time 1 and time 2, participants were defined as CMD cases if they had a record of CMD at the year or during the three preceding years of the survey. Participants with no CMD at time 1 and time 2, but recorded CMD during the four years following time 2, were considered incident CMD cases at time 3. Recovery from CMD after time 2 was indicated for participants with CMD at time 1 and time 2 if they had no record of CMD during the 4-year period following time 2 (ie, time 3).

Assessment of covariates

In all three studies, covariates were drawn from the year of the baseline survey of each individual. Information on sex, age, and marital status (married or cohabiting versus other) was obtained from the employers’ registers. The highest educational degree (high = university degree, intermediate = high school or vocational school, low = comprehensive school) was obtained from Statistics Finland’s register of completed education (26) through linkage using personal identification codes. From the baseline study wave questionnaires, we were able to obtain information on factors possibly affecting mental health: physical inactivity (based on weekly hours spent on leisure or commuting physical activity multiplied by the activity’s typical energy expenditure expressed as daily metabolic equivalent task hours, <14 hours/week was used as a cut-off point based on physical activity recommendations (27), smoking (current smoker versus not), and heavy alcohol consumption (>16 drinks/week for women, >21 drinks/week for men corresponding to the medium risk levels of daily consumption set by the World Health Organization) (28), as well as height and weight. Using height and weight we calculated body mass index (BMI) as weight in kg/height in meters squared (29). We also obtained information on chronic disease namely; diabetes, coronary heart disease, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and rheumatoid arthritis from the Drug Reimbursement Register, which contains information on persons entitled to special reimbursement for treatment of chronic conditions. As for cancers, we obtained information from the Finnish Cancer Registry, which covers all diagnosed cancers in Finland.

Statistical analyses

The overall analysis was divided into three steps.

Analysis 1

Using data from study 1, we examined the association between exposure to night work and the odds of incident CMD using logistic regression with generalized estimating equation (GEE). We used GEE-based approach to account for within-person correlation from those participants who contributed observations to two or three cycles. The analysis was adjusted for sex, age, education, marital status, body mass index, physical activity, current smoking, alcohol consumption and chronic disease.

Analysis 2

Using data from study 2, we examined the association between the exposure (moving from night to non-night work) and the outcome (the recovery from CMD) using logistic regression with GEE. The analysis was adjusted for the same covariates as Analysis 1.

Analysis 3

This analysis was carried out as a follow-up of study 1 results to investigate a potential selection bias and estimate the extent to which that bias was likely to alter the odds ratio (OR) of developing CMD of Study 1. Analysis 3 first examined the extent to which night workers who develop CMD tend to change their schedule back to non-night work (Study 3a). Using these results along with further calculations, we estimated the percentage of night work leavers and then derived formulae to recalculate the estimated OR of acquiring CMD after moving to night work in comparison to remaining in non-night work accounting for those leavers. We estimated the magnitude of turnover among new night workers (ie, those moving from non-night work at time 1 to night work at time 2) utilizing the observed proportion (P, %) of participants who moved back to non-night work between time 2 and time 3 (study 3a). Bias in study 1 would occur and remain undetected if this pattern of moving from non-night work to night work and back occurred proportionally more in those who developed CMD in night work and if their return to non-night work occurred before the next survey (and thus is not detected by 4-yearly measurements). To take the latter into account, the excess turnover in CMD cases was estimated conservatively based on a 2-year time window, ie, from half of the time 2 to time 3 quitters’ proportion (Pest = P/2, %) when correcting the estimated effect of moving to night work on CMD risk. Formulae for bias-corrected numbers are shown in table 1. To incorporate the uncertainty in the estimation, we modelled various scenarios varying this proportion from assumed underestimation to assumed overestimation, in addition to the best estimate. This was calculated based on study 1 population.

Table 1

Formula to calculate bias-corrected effect of moving from non-night work to night work on developing CMD: NTmis = Pest / (100 – Pest) × NT2 and NCmis = OR3 × O2 × NTmis / (OR3 × O2 + 1) where Pest=proportion of participants who moved from non-night to night work and back to non-night work before time 2 in Study 1; OR3=the effect of acquiring CMD on moving to non-night work among night workers based on Study 3a; NTmis=number of night workers misclassified as non-night workers at time 2 in Study 1; NCmis=number of CMD cases among the misclassified night workers in Study 1.

| Exposure | Observed numbers | Bias-corrected numbers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||

| N (total) | N (cases) | Odds | N (total) | N (cases) | Odds | OR | |

| Non-night work at T1 and T2 (reference) | NT1 | NC1 | O1 | NT1esta | NC1estb | O1estc | 1 |

| Non-night work T1 and night work at T2 (intervention) | NT2 | NC2 | O2 | NT2estd | NC2este | O2estf | ORestg |

Results

The eligible population of 46 010 employees for this study differed little from the base population (N=76 615) in terms of mean age (44.9 years vs 44.5 years), proportion of women (92% vs 89%), proportion of participants with high education (55% vs 52%) and prevalence of CMD (10% vs 11%). Participants in Study 1 (N=25 814), Study 2 (N=500) and Study 3 (N=5066) were drawn from the eligible population (figure 1). Their characteristics are shown in table 2.

Table 2

Characteristics of participant in studies 1, 2 andd 3 and their pseudo intervention and reference groups. [CMD=common mental disorder]

| Characteristic time 1 | Study 1a,b | Interventiona,b | Referencea,b | Study 2a,b | Interventiona,b | Referencea,b | Study 3aa,b | Interventiona,b | Referencea,b | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Night work | ||||||||||||||||||

| No | 25 814 | 100 | 665 | 100 | 25 149 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 500 | 100 | 127 | 100 | 373 | 100 | 5066 | 100 | 350 | 100 | 4716 | 100 |

| CMD | ||||||||||||||||||

| No | 25 814 | 100 | 665 | 100 | 25 149 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5066 | 100 | 350 | 100 | 4716 | 100 |

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 500 | 100 | 127 | 100 | 373 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||||||||

| Men | 2240 | 9 | 50 | 8 | 2190 | 9 | 40 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 32 | 9 | 400 | 8 | 34 | 10 | 366 | 8 |

| Women | 23 574 | 91 | 615 | 92 | 22 959 | 91 | 460 | 92 | 119 | 94 | 341 | 91 | 4666 | 92 | 316 | 90 | 4350 | 92 |

| Level of education | ||||||||||||||||||

| Low | 2480 | 10 | 31 | 5 | 2449 | 10 | 11 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 80 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 74 | 2 |

| Intermediate | 9265 | 36 | 262 | 39 | 9003 | 36 | 250 | 50 | 59 | 46 | 191 | 51 | 2102 | 41 | 155 | 44 | 1947 | 41 |

| High | 14 068 | 55 | 372 | 56 | 13 696 | 54 | 239 | 48 | 65 | 51 | 174 | 47 | 2884 | 57 | 189 | 54 | 2695 | 57 |

| Marital status | ||||||||||||||||||

| Cohabiting | 20 126 | 79 | 466 | 71 | 19 660 | 79 | 322 | 65 | 78 | 61 | 244 | 66 | 3841 | 76 | 240 | 69 | 3601 | 77 |

| Other | 5466 | 21 | 191 | 29 | 5275 | 21 | 173 | 35 | 49 | 39 | 124 | 34 | 1187 | 24 | 107 | 31 | 1080 | 23 |

| Physical activity | ||||||||||||||||||

| Active | 21 179 | 83 | 567 | 86 | 20 612 | 83 | 383 | 77 | 99 | 79 | 284 | 77 | 4273 | 85 | 294 | 85 | 3979 | 85 |

| Inactive | 4383 | 17 | 92 | 14 | 4291 | 17 | 113 | 23 | 27 | 21 | 86 | 23 | 757 | 15 | 53 | 15 | 704 | 15 |

| Current smoking | ||||||||||||||||||

| No | 21 498 | 85 | 532 | 82 | 20 966 | 85 | 357 | 73 | 97 | 79 | 260 | 71 | 4089 | 83 | 259 | 76 | 3830 | 83 |

| Yes | 3678 | 15 | 118 | 18 | 3560 | 15 | 130 | 27 | 26 | 21 | 104 | 29 | 848 | 17 | 80 | 24 | 768 | 17 |

| Heavy alcohol use | ||||||||||||||||||

| No | 23 089 | 90 | 602 | 91 | 22 487 | 90 | 420 | 84 | 106 | 83 | 314 | 85 | 4562 | 90 | 303 | 87 | 4259 | 91 |

| Yes | 2619 | 10 | 60 | 9 | 2559 | 10 | 78 | 16 | 21 | 17 | 57 | 15 | 493 | 10 | 46 | 13 | 447 | 9 |

| Chronic disease | ||||||||||||||||||

| No | 24 112 | 93 | 625 | 94 | 23 487 | 93 | 445 | 89 | 118 | 93 | 327 | 88 | 4849 | 96 | 329 | 94 | 4520 | 96 |

| Yes | 1702 | 7 | 40 | 6 | 1662 | 7 | 55 | 11 | 9 | 7 | 46 | 12 | 217 | 4 | 21 | 6 | 196 | 4 |

| Outcome (CMD) | ||||||||||||||||||

| No | 22 541 | 87 | 573 | 86 | 21 968 | 87 | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 3273 | 13 | 92 | 14 | 3181 | 13 | ||||||||||||

| Recovery from CMD | ||||||||||||||||||

| No | 400 | 80 | 91 | 72 | 309 | 83 | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 100 | 20 | 36 | 28 | 64 | 17 | ||||||||||||

| Move from night work to non-night work | ||||||||||||||||||

| No | 4103 | 81 | 254 | 73 | 3849 | 82 | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 963 | 19 | 96 | 27 | 867 | 18 | ||||||||||||

a Mean age: study 1 − 44.9 [standard deviation (SD) 7.9] years; intervention − 41.1 (SD 9.1) years; reference − 45.0 (SD 7.8) years. Study 2 − 44.7 (SD 7.3) years; intervention − 44.1 (SD 7.3) years; reference − 44.9 (SD 7.4) years. Study 3 − 42.1 (SD 7.6) years; intervention − 42.6 (SD 7.3) years; reference − 42.1 (SD 7.6) years.

b Body mass index: Study 1− 24.9 (SD 4.0) kg/m3; intervention − 24.9 (SD 4.0) kg/m3; reference − 24.9 (SD 4.0) kg/m3. Study 2 − 25.7 (SD 4.4) kg/m3; intervention − 24.6 (SD 4.0) kg/m3; reference − 26.1 (SD 4.4) kg/m3. Study 3 − 24.9 (SD 3.9) kg/m3; intervention − 25.2 (SD 4.0) kg/m3; reference − 24.9 (SD 3.9) kg/m3.

Analysis 1. Changing from non-night to night work as a risk factor for CMD

Of the 30 019 employees who reported working in non-night shifts at time 1 and who are not recorded to suffer from CMD at time 1 and time 2, 25 149 were in the reference group of non-night workers and 665 in the intervention group of night workers. At time 3, the incidence of acquiring CMD in the reference group was 12.7% with a total number of 3181 cases while the incidence of acquiring CMD in the intervention group was recorded as 13.8% with a total of 92 cases. The OR of acquiring CMD having non-night workers as the reference group is 1.03 (95% CI 0.82–1.30, P=0.46) (table 3, study 1). An OR of 1.03 with wide CI indicates that there was no evidence to suggest a higher odds of acquiring CMD among night compared to non-night workers.

Table 3a

Results from pseudo trials to examine the effect of (i) moving from non-night work to night work on acquiring common mental disorder (CMD) (study 1), (ii) moving from night to non-night work on CMD remission (study 2), (ii) acquiring CMD on choice of work schedule among night workers (study 3a).

| Outcome: Incident CMD at T3 | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Study 1 (exposure) | Na (total) | N (cases) | Incidence (%) | ORb | 95% CI | ORc | 95% CI |

| Non-night work at T1 and T2 (reference) | 25 149 | 3181 | 12.7 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Non-night work at T1 and night work at T2 (intervention) | 665 | 92 | 13.8 | 1.08 | 0.87–1.35 | 1.03 | 0.82–1.30 |

|

|

|||||||

| Outcome: Recovery from CMD at T3 | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Study 2 (exposure) | Nd (total) | N (cases) | Recovery (%) | ORb | 95% CI | ORc | 95% CI |

|

|

|||||||

| Night work at T1 and T2 (reference) | 373 | 64 | 17.2 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Night work at T1 and non-night work at T2 (intervention) | 127 | 36 | 28.4 | 1.93 | 1.23–3.02 | 1.99 | 1.20–3.28 |

|

|

|||||||

| Outcome: Moving from night work to non-night work at T3 | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Study 3a (exposure) | Ne (total) | N (cases) | Return from night to non-night work (%) | ORb | 95% CI | ORc | 95% CI |

|

|

|||||||

| Night workers with no CMD at T1 or T2 (reference) | 4716 | 867 | 18.4 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Night workers with no CMD at T1 but new CMD at T2 (intervention) | 350 | 96 | 27.4 | 1.68 | 1.31–2.15 | 1.68 | 1.30–2.17 |

Table 3b

Results from pseudo trials to examine the bias-corrected effect of moving to night work on acquiring CMD (Study 3b).

| Study 3b (exposure) | Observed numbers in study 1 | Bias-corrected numbers outcome: CMD at T3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| N (total) | N (cases) | Odds | N (total) | N (cases)a | Odds | ORb | 95% CI | |

| Non-night work at T1 and T2 (reference) | 25 149 | 3181 | 0.145 | 24 983 | 3146 | 0.144 | 1.00 | |

| Non-night work T1 and night work at T2 (intervention) | 665 | 92 | 0.161 | 831 | 127 | 0.180 | 1.25 | 1.03–1.52 |

Analysis 2. The impact of moving from night to non-night work on the recovery from CMD

Of the 500 participants with CMD at time 1 and time 2, 373 were in the reference group of night workers and 127 in the intervention group of non-night workers. At time 3, the recovery from the CMD in the reference group was 17.2% with a total number of 64 cases and the recovery from CMD in the intervention group was recorded as 28.4% with a total of 36 cases. The OR of recovery from CMD having night workers as the reference group was 1.99 (95% CI 1.20–3.28, P=0.004) (table 3, study 2). This indicates that night workers who had CMD have substantially higher odds of recovering from CMD when moving their work schedule to non-night work compared to maintaining a night work schedule. This finding remained in a subsidiary analysis in which CMD was defined using only records of sickness absences (3.66, 95% CI 1.16–11.5, N=84).

Analysis 3. Estimation of bias-corrected association between night work and CMD

Study 3a in table 3 shows results from the analyses addressing the question whether night workers tend to change their work schedule and move to non-night work if they found out they suffer from one or more CMD. Night workers who developed a CMD had higher odds of moving their schedule back to non-night work compared to night workers who did not develop CMD (OR 1.68, 95% CI 1.31–2.15). We then re-estimated the OR of acquiring CMD for those moving from non-night to night work compared to those remaining in non-night work under the assumption that night workers who developed CMD did not remain as night workers but moved their schedule back to non-night work before the next survey four years later. In all, 199 (39%) of new night workers at time 2 (N=511) moved their work schedule back to non-night work between time 2 and time 3. The estimated proportion of new night work leavers after time 1 who had quit night work before time 2 was 20%.

With this estimated number, we accounted for those leavers in the results of study 1. The results from the estimated situation showed that if leavers were 20%, the corrected OR of acquiring CMD having non-night workers as the reference group would be 1.25 (95% CI 1.03–1.52), suggesting higher odds of acquiring CMD among night compared to non-night workers in a statistically significant way (table 3, study 3b). In a sensitivity analysis of alternative assumed proportions of leavers, the corresponding OR are 1.30 (95% CI 1.08–1.56) with this proportion being 25%, 1.33 (95% CI 1.12–1.60) with a proportion of 30% (assumed overestimate of leavers). It would be 1.22 (95% CI 1.00–1.49) with a proportion of 15%, and 1.18 (95% CI 0.96–1.46) with 10% (assumed underestimate). Thus, the bias-corrected excess CMD risk among those who start night work appears to be robust to alternative scenarios of returning back from night to non-night work as a consequence of CMD.

Discussion

This study shows a doubling of odds of recovery from CMD when affected night workers change their schedule to non-night work compared to affected night workers who continue to work night shifts. We found no elevated odds for developing CMD among night compared to non-night workers, but the lack of association was mainly attributable to the greater likelihood of night workers with CMD to move back to non-night work. An estimation assuming no night worker moved back to non-night work suggested that change from non-night to night work is associated with a 1.2-fold increased risk in CMD.

A randomized controlled trial is the most effective design to infer causality. However, for ethical obligations, it can only be used to investigate the effect of a protective factor. The methods we used in the present paper allowed us to simulate the effect of a non-randomized controlled trial to investigate the effect of a risk factor as an intervention (night work, covered in study 1) because it was conducted on observational data as a pseudo trial. This means that no one was obliged to endure the effect of the risk factor. Using the same design, we then investigated the effect of a potential protective factor (moving from night to non-night work, covered in study 2). Applying this method was only possible because of the existence of observational data with ≥3 data collection time points. Our method does not rely on randomization and is, therefore, subject to confounding and bias, but probably to a lesser extent than traditional prospective studies with a single baseline assessment and follow-up of the outcome.

The sample used in the study covered employees from different occupations exposed to night work within the social and healthcare sectors and from different towns within Finland and any differences between the base population and the eligible sample were small. These issues support generalizability of our findings in this specific context. The duration of the follow-up is one of the strength of this study − using a longitudinal design with a 4-year window for the exposure and 4-year period to follow-up the outcome − compared to other studies that base their results on information collected at one time point. This can be a valuable source to assess the current situation and prevalence of a certain outcome in relation to a specific risk/protective factor but limits the possibility to infer causality between them.

We assessed the outcome (acquiring CMD or recovery from CMD) objectively to minimize the problems related to self-reports of mental health, which may vary substantially among individuals and invalidate results. We used two indicators to assess mental health, records of sickness absence due to mental disorders and records of anti-depressants purchase. As the exposure was assessed with self-reports, risk of common methods bias was minimized. However, the register-based indicators may not provide a conclusive status of the outcome. The significant difference in the number of participants allocated to reference and intervention groups in all three studies was unavoidable in this study design since it is a reuse of an existing observational data mimicking a non-randomized trial. The assessment of night work was done in 4-year interval by a rather crude measure with one of the response options (“other form of irregular working hours”) not allowing detection of night workers. This may have caused some misclassification, although the proportion of participants with unspecified “irregular working hours” was only 2%.

Studies show that resilience to the effect of night work is different among individuals and characteristic groups, for example, a study conducted on a population level stated that women’s mental health was more adversely affected by varied shift patterns, while night work had a greater negative impact on men’s mental health (30). A German study stated that about 15% of all healthy adults are insufficiently adaptable to night shift work and that those individuals carry a particularly high health risk if regularly participating in night shift work (31).

Taken together, the findings from observational repeat data analyzed as a series of pseudo trials suggest that moving from non-night to night work may increase the risk of CMD, but − due to the tendency of affected individuals to move back to non-night work − no excess risk was observed. For night workers with CMD, moving to non-night work was found to be associated with substantially improved recovery rates. Future studies may use similar designs to the ones used in this paper on populations from different parts of the world and present evidence that could be beneficial for following systematic reviews and meta-analyses to reach definite conclusions concerning night work and CMD. Also developing psychometric tools to assess the degree to which an individual is resilient to the adverse effects of irregular work patterns, including shift and night work, would be useful facilitating preventive interventions for the safety of those prone to shift work disorder and better allocation of human resources.