According to the Global Health Observatory data repository of the World Health Organization (WHO), 788 000 deaths by suicide occurred worldwide in 2015, representing an annual age-standardized suicide rate of 10.7 per 100 000. Suicide is a multifactorial event, associated with characteristics of societies, communities, health systems and individuals (1). Among these, work characteristics appear to play a complex role. On the one hand, work is protective: individuals seeking employment have a higher risk of suicide than those who are employed (2). However the majority of suicides occur among individuals who are working (3) and some trades appear to confer especially high risk (eg, agriculture, the health sector, police and military) (4). Additionally, there is an occupational gradient in relation to suicide, whereby individuals in less qualified occupations are more likely to commit suicide than those who are at the top of the hierarchy (5). To date, despite abundant anecdotal evidence regarding the role of psychosocial work factors with regard to suicide, this association remains unclear (2, 6). Moreover, relations between long-term work patterns and suicide are not fully described.

Methods

Study population

The GAZEL cohort study was established in 1989 (7). Briefly, the target population consists of employees of the French national gas and electricity company (Electricité de France-Gaz de France – EDF-GDF) who, up until the company was privatized in the 2000s, benefited from job stability and opportunities for occupational mobility. Typically, employees were hired when they were in their 20s and stayed with the company until retirement (usually around 55 years of age). This offers the unique opportunity to characterize participants’ occupational trajectories across their whole career. Since inception, <1% of participants have been lost to follow-up.

In 1989, GAZEL recruited 20 625 volunteers (15 011 men and 5614 women), aged 35–50 years, who since then receive an annual questionnaire collecting data on health, lifestyle, individual, familial, social, occupational risk factors and life events. Prior to privatization, EDF-GDF had an occupational health department, a medical insurance, a detailed health surveillance system and paid employees’ retirement pensions thereby allowing for a thorough follow-up. The GAZEL study received approval from the national commission overseeing ethical data collection in France (Commission Nationale Informatique et Libertés).

For the present analyses, we restricted the study sample to 20 452 participants with data on occupational grade who were alive and part of the cohort in 1993 when key covariates were measured (figure 1). During the follow-up between 1993 and 2014 [median of 21.9, standard deviation (SD) 3.2, years], 2081 deaths occurred including 73 suicides.

Measurements

Mortality. The date of death was obtained from company records. The cause of death, available from the French national cause-of-death registry (CépiDC, INSERM) and linked to GAZEL, was available from baseline (ie, 1 January 1993) to 31 December 2014 and coded using the International Classification of Disease (ICD). Completed suicides correspond to the codes E950–E959 (9th revision) and X60–X84 (10th revision).

Occupational grade. Occupational grade was obtained from company records, from the time of hiring (between 1953 and 1988) to the baseline for this analysis (1993), leading to a mean time period of 25.0 years (SD 6.5), prior to suicide assessment (1993–2014, 22-year follow-up). Occupational grade was coded according to the French national job classification (Institut National de la Statistique et des Etudes Economiques: INSEE): high grade (managers), intermediate grade (associate professionals and technicians), clerks, and manual workers.

Covariates

Covariates were measured at baseline (1993), except retirement ascertained throughout the follow-up. Socio-demographic characteristics included age, sex, partner status (married/living with a partner versus single/divorced/separated/widowed) and retirement (no versus yes). Smoking and alcohol consumption were assessed using a self-administered questionnaire. Smoking status was categorized as: non-smoker, former smoker or smoker (≥1 cigarette/day). Alcohol use, assessed by the number of alcoholic drinks per week, was categorized as none, moderate (1–27 for men, 1–20 for women) or heavy (≥28 for men, ≥21 for women). Psychosocial characteristics included stressful life events 12 months prior the survey (hospitalization, relative’s death, relative’s hospitalization, relative’s unemployment; 0 versus ≥1), depressive symptoms were measured using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CESD) scale (continuous score 0–60) and cognitive hostility, a personality trait linked with increased suicide risk (8), was assessed with the Buss and Durkee Hostility Inventory (the sub-scales “resentment” and “suspicion” of the BDHI; continuous score 0–18).

Statistical analysis

Occupational trajectories from the time of hiring (1953–1988) to baseline (1993) were defined using group-based trajectory models (9). This method empirically groups together individuals with similar trajectories over time. Models including 2–6 trajectories were tested. The two criteria used to determine the optimal number of trajectories were (i): Bayesian information criterion (lower absolute values correspond to better fit) and (ii) posterior probabilities of group assignment (the likelihood that an individual belongs to a given trajectory; all trajectories should have a mean posterior probability ≥0.70 and each trajectory contains ≥5% of participants). We also verified that each trajectory included ≥5% of participants. This method was implemented with the traj package (available from http://www.andrew.cmu.edu/user/bjones/traj) for Stata 14 (StataCorp, College Station, YX, USA).

Missing covariate data were imputed using multiple imputations (40 datasets), with the fully conditional specification (FCS) method (10), based on all available data on suicide and covariates.

To examine relationships between occupational trajectories and suicide deaths we used Cox proportional-hazards regression models with age as the time scale. The proportional hazards assumptions were confirmed by Schoenfeld tests. Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of incident suicide were computed from 1993 to the date of suicide, death by another cause, or 31 December 2014, whichever occurred first. Statistical analyses controlled for potentially confounding variables selected based on the literature and formal bivariate tests (considered relevant at P≤0.1). In Model 1, HR were adjusted for socio-demographic factors (sex, partner status and retirement). Model 2 additionally controlled for smoking and alcohol use. Model 3 further controlled for psychosocial characteristics (depressive symptoms, stressful life events, cognitive hostility). Confounding variables were ascertained at baseline (1993), except retirement used as a time-varying covariate.

Sensitivity analysis

To test the robustness of our findings, we conducted further sensitivity analyses. First, in order to address the possibility that some people might describe conditions at baseline when they actually consider committing suicide, we repeated the Cox proportional-hazards regression models in the main analysis by delaying the start of the follow-up by one (follow-up 1994–2014), two (follow-up 1995–2014) and three years (follow-up 1996–2014). Second, in order to address the possibility that some people commit suicide in older age due to being alone (eg, widowed) or seriously ill (eg, cancer), we repeated the Cox proportional-hazards regression models in the main analysis by ending the follow-up at 70 and 65 years of age. Third, in order to address the possibility that occupational grade at one point in time might predict suicide risk similarly to occupational trajectories, we repeated the Cox proportional-hazards regression models in the main analysis using occupational grade at baseline (1993) as independent variable.

Results

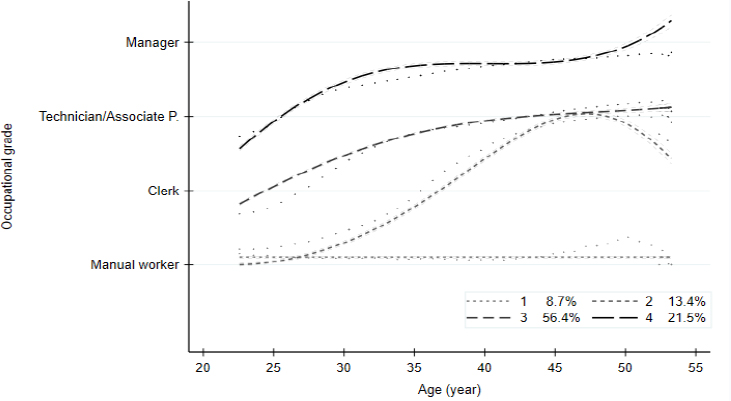

Figure 2 shows participants’ occupational trajectories. Four trajectories were identified (i): stable manual workers (8.7%) (ii); manual workers with career development (13.4%) (iii); clerks with career development (56.4%) (iv); intermediate/high occupational grade workers with career development (21.5%). Mean posterior probabilities were estimated between 0.85–0.97.

Figure 2

Occupational trajectories according to age from the time of hiring to 1993 (study baseline) of the GAZEL study participants (n=20,600). Trajectory 1, stable manual workers; trajectory 2, manual workers with career development; trajectory 3, clerks with career development; trajectory 4, participants with intermediate/high occupational grade with career development.

Baseline participant characteristics as a function of occupational trajectories are presented in table 1. Among the 20 452 GAZEL cohort members included in the analysis, 1755 (8.6%) were stable manual workers, 2315 (11.3%) were manual workers with career development, 12 434 (60.8%) were clerks with career development and 3948 (19.3%) were intermediate/high occupational grade workers with career development.

Table 1

Participants’ baseline characteristics (1993) by occupational trajectory: the GAZEL cohort study, N=20 452, chi-square (categorical variables) and t-tests (continuous variables), P-value. Results are of participants with imputed missing data. [CESD=Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression: SD=standard deviation].

| Variables | Trajectory 1a (N=1 755) | Trajectory 2b (N=2 315) | Trajectory 3c (N=12 434) | Trajectory 4d (N=3 948) | P-valuee | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

| N | % | Mean | SD | N | % | Mean | SD | N | % | Mean | SD | N | % | Mean | SD | ||

| Sex | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||||

| Men | 1727 | 98.4 | 2274 | 98.2 | 7497 | 60.3 | 3382 | 85.7 | |||||||||

| Women | 28 | 1.6 | 41 | 1.8 | 4937 | 39.7 | 566 | 14.3 | |||||||||

| Age | 47.8 | 0.07 | 48.4 | 0.06 | 46.9 | 0.03 | 47.7 | 0.05 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Partner status | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||||

| Married/living with a partner | 1597 | 91.0 | 2122 | 91.7 | 10657 | 85.7 | 3569 | 90.4 | |||||||||

| Single/divorced/separated/widowed | 158 | 9.0 | 193 | 8.3 | 1778 | 14.3 | 379 | 9.6 | |||||||||

| Smoking | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||||

| Non-smokers | 616 | 35.2 | 804 | 34.8 | 5913 | 47.6 | 1662 | 42.1 | |||||||||

| Former smokers | 719 | 40.9 | 1015 | 43.8 | 4067 | 32.7 | 1507 | 38.2 | |||||||||

| Smokers | 420 | 23.9 | 496 | 21.4 | 2454 | 19.7 | 779 | 19.7 | |||||||||

| Alcohol use | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||||

| None | 193 | 11.0 | 230 | 9.9 | 1836 | 14.8 | 326 | 8.3 | |||||||||

| Moderate | 1223 | 69.7 | 1686 | 72.9 | 9214 | 74.1 | 3133 | 79.3 | |||||||||

| Heavy | 339 | 19.3 | 399 | 17.2 | 1384 | 11.1 | 489 | 12.4 | |||||||||

| Stressful life events (previous 12 months) | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1025 | 58.4 | 1318 | 56.9 | 7226 | 58.1 | 2451 | 62.1 | |||||||||

| ≥1 | 730 | 41.6 | 997 | 43.1 | 5208 | 41.9 | 1497 | 37.9 | |||||||||

| CESD score | 13.5 | 0.27 | 12.5 | 0.21 | 14.0 | 0.11 | 11.8 | 0.15 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Cognitive hostility score | 7.3 | 0.11 | 6.5 | 0.09 | 6.2 | 0.04 | 4.9 | 0.06 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Suicide deaths | 0.032 | ||||||||||||||||

| No | 1743 | 99.3 | 2303 | 99.5 | 12394 | 99.7 | 3939 | 99.8 | |||||||||

| Yes | 12 | 0.7 | 12 | 0.5 | 40 | 0.3 | 9 | 0.2 | |||||||||

During follow-up (median of 21.9, SD 3.2, years), 73 suicide deaths occurred (0.4% of the sample): 12 (0.7%) among stable manual workers, 12 (0.5%) among manual workers with career development, 40 (0.3%) among clerks with career development and 9 (0.2%) among intermediate/high occupational grade workers with career development.

Table 2 shows associations between occupational trajectories and suicide. After adjustment for socio-demographic characteristics (Model 1), participants who were stable manual workers (HR 2.57, 95% CI 1.08–6.15) had an increased risk of suicide, compared with participants with intermediate/high occupational grade with career development. Additional adjustment for health behaviors (Model 2; HR 2.39, 95% CI 1.00–5.73) and psychosocial characteristics (Model 3; HR 2.02, 95% CI 0.82–4.95) reduced the magnitude of this association and rendered it statistically non-significant. The risk of suicide among manual workers (HR=1.99, 95% CI 0.83–4.76) or clerks (HR 1.59, 95% CI 0.76–3.30) who experienced career development was not statistically significant.

Table 2

Association between occupational trajectory and risk of suicide (1993–2014): the GAZEL cohort study, N=20 452, Cox proportional-hazards regression models. Results are of participants with imputed missing data. Confounding variables were used at baseline (1993), except retirement that was use as time-varying covariates in the analysis. [PY= person-years; IR=incidence rate; HR=hazard ratio; CI=confidence interval].

| Occupational trajectories | N suicide death/N | PY | IR per 100 000 PY | Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value | ||||

| Trajectory 1d | 12/1755 | 35 779 | 33.54 | 2.57 | 1.08–6.15 | 0.033 | 2.39 | 1.00–5.73 | 0.050 | 2.02 | 0.82–4.95 | 0.124 |

| Trajectory 2e | 12/2315 | 48 310 | 24.84 | 1.99 | 0.83–4.76 | 0.121 | 1.95 | 0.81–4.66 | 0.134 | 1.78 | 0.74–4.31 | 0.201 |

| Trajectory 3f | 40/12 434 | 262 293 | 15.25 | 1.59 | 0.76–3.30 | 0.218 | 1.52 | 0.73–3.17 | 0.266 | 1.40 | 0.67–2.95 | 0.373 |

| Trajectory 4g | 9/3948 | 83 929 | 10.72 | reference | reference | reference | ||||||

In the first sensitivity analysis (table 3), we delayed the start of the follow-up by one (follow-up 1994–2014), two (follow-up 1995–2014) and three years (follow-up 1996–2014). Statistical analyses were respectively based on 20 395 (69 suicides), 20 352 (63 suicides), and 20 305 (57 suicides) individuals. Overall, the results were similar to the main analysis. The magnitude of the association was highest for stable manual workers (fully adjusted association statistically significant when the start of the follow-up was delayed by three years) and for manual workers with career development

Table 3

Association between occupational trajectory and risk of suicide delaying the beginning of follow-up by one, two, or three years: the GAZEL cohort study, Cox proportional-hazards regression models. Results are of participants with imputed missing data. Confounding variables were used at baseline (1993), except retirement that was use as time-varying covariates in the analysis. [PY=person-years; IR=incidence rate; HR=hazard ratio; CI=confidence interval].

| Occupational trajectories | N suicide death/N | PY | IR per 100 000 PY | Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value | ||||

| Beginning of follow-up delayed by one year (1994–2014) | ||||||||||||

| Trajectory 1d | 12/1746 | 34 028 | 35.26 | 2.57 | 1.08–6.15 | 0.034 | 2.43 | 1.01–5.82 | 0.047 | 2.05 | 0.84–5.03 | 0.115 |

| Trajectory 2e | 11/2308 | 45 997 | 23.08 | 1.82 | 0.75–4.42 | 0.187 | 1.78 | 0.73–4.33 | 0.204 | 1.62 | 0.66–3.99 | 0.292 |

| Trajectory 3f | 37/12,399 | 249 876 | 14.81 | 1.48 | 0.71–3.10 | 0.299 | 1.43 | 0.68–3.00 | 0.345 | 1.32 | 0.62–2.79 | 0.471 |

| Trajectory 4g | 9/3942 | 79 973 | 11.25 | reference | reference | reference | ||||||

| Beginning of follow-up delayed by two years (1995–2014) | ||||||||||||

| Trajectory 1d | 12/1739 | 32 288 | 37.17 | 2.95 | 1.19–7.27 | 0.019 | 2.82 | 1.14–6.98 | 0.025 | 2.47 | 0.98–6.25 | 0.056 |

| Trajectory 2e | 11/2300 | 43 695 | 25.17 | 2.05 | 0.82–5.14 | 0.125 | 2.03 | 0.81–5.08 | 0.133 | 1.89 | 0.75–4.81 | 0.179 |

| Trajectory 3f | 32/12 376 | 237 491 | 13.47 | 1.41 | 0.64–3.10 | 0.394 | 1.37 | 0.62–3.02 | 0.434 | 1.29 | 0.58–2.86 | 0.536 |

| Trajectory 4g | 8/3937 | 76 035 | 10.52 | reference | reference | reference | ||||||

| Beginning of follow-up delayed by three years (1996–2014) | ||||||||||||

| Trajectory 1d | 12/1730 | 30 557 | 39.27 | 3.49 | 1.36–8.95 | 0.009 | 3.40 | 1.32–8.76 | 0.011 | 2.96 | 1.13–7.79 | 0.028 |

| Trajectory 2e | 11/2291 | 41 402 | 26.57 | 2.39 | 0.92–6.22 | 0.075 | 2.38 | 0.91–6.20 | 0.077 | 2.21 | 0.84–5.83 | 0.109 |

| Trajectory 3f | 27/12 358 | 225 126 | 11.99 | 1.38 | 0.59–3.23 | 0.452 | 1.36 | 0.58–3.17 | 0.479 | 1.27 | 0.54–2.99 | 0.586 |

| Trajectory 4g | 7/3926 | 72 105 | 9.71 | reference | reference | reference | ||||||

In a second sensitivity analysis (table 4), we censured the follow-up at 70 and 65 years of age. Statistical analyses were based on 20 452 individuals and respectively 70 and 65 suicides occurred. The magnitude of observed associations was reduced but conclusions were unchanged compared to the main analysis.

Table 4

Association between occupational trajectory and risk of suicide with the end of follow-up at 70 or 65 years of age: the GAZEL cohort study, Cox proportional-hazards regression models. Results are of participants with imputed missing data. Confounding variables were used at baseline (1993), except retirement that was use as time-varying covariates in the analysis. [PY=person-years; IR=incidence rate; HR=hazard ratio; CI= confidence interval].

| Occupational trajectories | N suicide death/N | PY | IR per 100 000 PY | Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value | ||||

| End of follow-up at 70 years | ||||||||||||

| Trajectory 1d | 12/1755 | 34 224 | 35.06 | 2.54 | 1.06–6.07 | 0.036 | 2.34 | 0.98–5.61 | 0.057 | 2.01 | 0.82–4.92 | 0.127 |

| Trajectory 2e | 10/2315 | 45 488 | 21.98 | 1.67 | 0.67–4.13 | 0.269 | 1.61 | 0.65–4.01 | 0.302 | 1.49 | 0.59–3.75 | 0.393 |

| Trajectory 3f | 39/12434 | 251 458 | 15.51 | 1.52 | 0.73–3.18 | 0.263 | 1.45 | 0.69–3.02 | 0.324 | 1.35 | 0.64–2.85 | 0.429 |

| Trajectory 4g | 9/3948 | 79 628 | 11.30 | reference | reference | reference | ||||||

| End of follow-up at 65 years | ||||||||||||

| Trajectory 1d | 10/1755 | 28 826 | 34.69 | 2.07 | 0.83–5.14 | 0.116 | 1.89 | 0.76–4.71 | 0.170 | 1.62 | 0.64–4.12 | 0.313 |

| Trajectory 2e | 8/2315 | 37 301 | 21.45 | 1.34 | 0.51–3.46 | 0.564 | 1.28 | 0.49–3.34 | 0.619 | 1.19 | 0.45–3.13 | 0.734 |

| Trajectory 3f | 38/12434 | 215 547 | 17.63 | 1.46 | 0.70–3.05 | 0.318 | 1.38 | 0.66–2.89 | 0.394 | 1.29 | 0.61–2.73 | 0.509 |

| Trajectory 4g | 9/3948 | 66 454 | 13.54 | reference | reference | reference | ||||||

In a third sensitivity analysis (table 5), we examined the association between occupational grade measured at one point in time (baseline, 1993) and suicide. After adjustment for socio-demographic characteristics (Model 1), manual workers (HR 2.58, 95% CI 1.07–6.27) and participants with intermediate grade (HR 2.34, 95% CI 1.20–4.53) had an increased risk of suicide, compared with participants with high grade. Additional adjustment for health behaviors (Model 2) and psychosocial characteristics (Model 3) reduced the magnitude of these associations leaving only the association between participants with intermediate grade and risk of suicide statistically significant (HR=2.03, 95% CI 1.04–3.99). Overall, the results were different from the main analysis.

Table 5

Association between occupational grade at baseline (1993) and risk of suicide (1993–2014): the GAZEL cohort study, N=20 452, Cox proportional-hazards regression models. Results are of participants with imputed missing data. Confounding variables were used at baseline (1993), except retirement that was use as time-varying covariates in the analysis. [PY=person-years; IR=incidence rate; HR=hazard ratio; CI=confidence interval].

| Occupational grade at baseline (1993) | N suicide death/N | PY | IR per 100 000 PY | Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value | ||||

| Manual worker | 9/1529 | 31 156 | 28.89 | 2.58 | 1.07–6.27 | 0.036 | 2.41 | 0.99–5.87 | 0.052 | 2.05 | 0.83–5.07 | 0.122 |

| Clerk | 5/1841 | 38 581 | 12.96 | 2.27 | 0.76–6.83 | 0.143 | 1.99 | 0.66–6.00 | 0.219 | 1.64 | 0.53–5.02 | 0.389 |

| Intermediate graded | 48/11 507 | 242 150 | 19.82 | 2.34 | 1.20–4.53 | 0.012 | 2.22 | 1.14–4.31 | 0.019 | 2.03 | 1.04–3.99 | 0.039 |

| High gradee | 11/5575 | 118 422 | 9.29 | reference | reference | reference | ||||||

Discussion

Using data from a 20 456 middle-aged workers participating in a long-term cohort study, we identified four career-long occupational trajectories, of which one was characterized by persistent low occupational grade with no career development and three identified individuals who experienced career development. Over the course of a 22-year follow-up, compared to workers with intermediate/high occupational grade who experienced career development, stable manual workers were at elevated risk of suicide. In addition, manual workers and clerks with career development displayed intermediate levels of risk, suggesting a gradient between career-long trajectories and suicide. This association was partly explained by psychosocial characteristics such as depression, stressful life events and personality characteristics. Finally, we showed that suicide risk associated with occupational trajectories was different than suicide risk associated with occupational grade at one point in time.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the association between long-term occupational trajectories and suicide, showing that beyond occupational characteristics at one specific point in time, long-term employment patterns shape suicide risk. The present findings should be interpreted in light of some limitations. First, although the GAZEL cohort covers most regions of France and a wide range of occupations, it is not representative of the general population. In particular, GAZEL only included salaried workers (farmers, the self-employed, the unemployed, or individuals with unstable jobs are not in the sample) and EDF-GDF employees did not experience downward career mobility or job loss. Additionally, GAZEL participants have been shown to be in better health than EDF-GDF employees and the general population of France (11). Lower mortality by suicide was observed in the GAZEL cohort compared to the French population with the same age and with similar follow-up, with a standardized mortality ratio for suicide of 0.72 [0.58–0.89]. Thus, relations between occupational trajectories and suicide in the population at large may be stronger than we report. Second, given the limited number of suicides in our study, our analyses may have lacked statistical power. Thus, the association between occupational trajectory and suicide became statistically non-significant after controlling for psychosocial characteristics, but the HR was nevertheless 2.02. Moreover, due to the trajectory profiles of the population studied, we were only able to compare stable trajectory and career development trajectory in manual workers. Our results indicate that stable manual workers had a higher risk of suicide than manual workers with career development but the difference was not statistically significant suggesting that more statistical power is needed to compare stable and upward career trajectories; therefore confounding by occupational grade cannot be ruled out. Third, the use of ICD codes to identify suicide deaths could be conservative, as coders may use alternative options when available (1). Fourth, although we controlled for a wide range of potentially confounding variables, we cannot exclude the possibility of residual confounding from unmeasured variables, such as prior suicide attempts.

Despite these limitations, the main strengths of this study include the large number of participants, a longitudinal design, complete data on participants’ mortality, and the possibility to control for key confounders. This study makes a unique contribution by suggesting that career-long occupational trajectories are associated to the risk of suicide over an extended follow-up period. It also underscores the importance of considering occupational trajectories rather than only occupational grade at one point in time in studies aimed at examining the role of long-term factors in relation to the risk of suicide in order to identify who is most at highest risk and to prevent suicide.

Persistently low occupational grade could be related to an elevated risk of suicide. The role of psychosocial characteristics such as depression and personality traits in this association suggests that some individuals could be especially vulnerable to the consequences of limited opportunities for occupational advancement. Moreover, the lack of career development could also contribute to depressive symptoms and hostility. Further studies are needed to identify specific aspects of the occupational environment that may contribute to the excess risk of suicide associated with persistent low occupational grade and ways to protect the most vulnerable workers.