Sickness absence (SA) indicates poor health in working populations. Research has shown that workers with frequent long-term SA are at high risk for disease-related and all-cause mortality (1–3). Moreover, certain health-related conditions such as severe depressive symptoms and physical complaints, and high physical job demands prolong the duration of SA for workers who are already on sick leave for more than four weeks (4–6). Long-term SA is medically-certified and may last for several consecutive weeks or months. The duration of long-term SA varies across countries and may start for example at three weeks in Denmark or four weeks in UK and US (7, 8). Short-term work absences typically last one to two weeks at most and may be related to an acute illness, work stress or to fulfill family or social responsibilities (9, 10).

Social insurance agencies and institutions bear an enormous cost burden related to SA, including medical care, paid sick leaves, staff replacements and overtime, and therefore strive to minimize them. For example, employers in Sweden are responsible during the first two weeks for compensating employees who are on sick leave, after which the financial responsibility is transferred to the social insurance agency (11). In Netherlands, the compensation period covered by the employer is much longer, lasting 104 weeks, after which the sick employee becomes eligible for work disability (12), a condition that is more permanent and indicates exit from the labor workforce. Conversely, there are no federal legal requirements for paid SA for employees in the US. Ten US states mandate paid SA but these mostly depend on employment contracts and benefits (13, 14).

SA management is a major challenge because a myriad of personal, workplace, and economic factors are at play (15). Fatigue as a risk factor for SA has been of research interest in the occupational literature. Three decades ago, Hackett and colleagues (16) conducted one of the earlier studies on absenteeism, examining Canadian hospital nurses to show the prospective association between feeling tired (as an absence-inducing event) and actual absence from work.

Fatigue is prevalent in the workforce. In Europe, 22.5% of workers reported overall fatigue, which was one of the most commonly reported symptoms after backache (24.7%) and muscular pains (22.8%) (17). In the US, fatigue was estimated at 37.9% over a period of two weeks (18). In the workplace, fatigue creates a safety hazard not only for the workers but also for others and the environment (eg, oil spills, fires).

A simple perspective of fatigue views it as a symptom of tiredness, but it can also be viewed as a condition with multiple components. With the latter being more accepted, fatigue is conceptualized as a subjective experience where feelings of tiredness weaken or impair an individual’s physical, mental and/or psychosocial functioning (19–21). Most of the fatigue resulting from work activities is transient, and resolves with rest and sleep (ie, acute fatigue). However when recovery is incomplete during non-work hours, fatigue accumulates and becomes more chronic in nature. In a study of Finnish industrial workers who were followed over a period of 28 years, incomplete recovery from work was found to increase the hazard for cardiovascular mortality by 1.54 times (22). Fatigued employees are also susceptible to developing psychological problems and stress-related illnesses (23).

Often the words fatigue and sleepiness are used interchangeably among workers. Despite commonalities, each phenomenon is different from the other. Sleepiness is a normal physiologic condition defined as the propensity to fall asleep and is relieved only by sleep (24, 25). Fatigue on the other hand is a response to extended periods of wakefulness, sleep loss, and prolonged physical and mental exertion that is relieved by rest and sleep (24). From an occupational standpoint, most fatigue arises from circadian misalignments (sleeping at a time other than during the night due to shiftwork), lack of sleep depth, high workload and an adverse work environment (24). Other risk factors such as health problems and certain personal characteristics (eg, age, marital and caregiver status) also contribute to fatigue.

A number of longitudinal studies primarily from Europe have examined the association between fatigue and SA in different occupations. However, no systematic review of this relationship has been done to date. This gap may be related to the outcome of SA that is strongly rooted in legislation and culture, compensation benefits, SA insurance practices, and employer-employee contracts, as well as researchers’ study objectives. In a systematic review on measures of SA, Hensing (26)reported five different approaches to quantifying this outcome: frequency, length, incidence rate, cumulative incidence, and duration of SA days within SA episodes. This presents a challenge to compare and contrast study findings across countries that have different legal SA systems. Another gap may be related to the symptom of fatigue that is non-specific in nature and can be a precursor to or byproduct of illness and/or working conditions.

Therefore, the purpose of this paper was to examine and synthesize the existing literature on fatigue and SA in workers. We presented the synthesis by country because of SA differences in social insurance systems and culture. This systematic review aimed to determine: (i) if there is a conclusive evidence of this prospective relationship, (ii) the duration of SA that can be of long-term or short-term and (iii) the type of fatigue that is related to SA. Finally, we conducted a meta-analysis to quantify the relationship between fatigue and SA in the working population.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis followed the PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses) guidelines for reporting of findings. No ethical approval was needed since the meta-analysis is based on published data.

Eligibility criteria

Longitudinal cohort studies (prospective and retrospective) that examined the prospective relationship between fatigue and SA in the working population were eligible for this review. The inclusion criteria were: (i) fatigue being defined as a symptom (eg, tiredness, being tired, lack of energy, or weariness) or construct (unidimensional or multidimensional in nature), (ii) SA or absenteeism defined as being absent from scheduled work, of short, intermediate or long-term in duration (absent days), or by the number of absence episodes from work, (iii) the population of interest being workers or employees from all occupations and disciplines, and (iv) published in English only. There were no restrictions on publication date. The exclusion criteria included studies of cross-sectional in design, studies that focused on “chronic fatigue syndrome” cases, if assessment of fatigue as an item was part of a sleep or depression scale, data not in aggregate form, SA in patient groups, and employees who were already on sick leave.

Search strategy

The first author and a librarian conducted a literature search independently. Five databases were searched: PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and Cochrane CENTRAL. The main keywords were: fatigue, tired, exhaustion, weariness, worker, employee, work, sickness, absence, absenteeism, sick leave, and absent. The last day of retrieval was 17 March 2016. A hand search of reference lists of systematic reviews on SA yielded no additional papers. Using the same search strategy, the literature search was updated on 2 May 2018 to include any recent studies that were published since the primary search of this review.

We present here the electronic search strategy for PubMed.

(fatigue[tiab] OR “fatigue”[mesh] OR exhaust*[tiab] OR tired*[tiab] OR weariness[tiab] OR burnout[tiab] OR “burnout, professional”[mesh] OR “work schedule tolerance”[mesh])

AND (absent*[tiab] OR absence[tiab] OR absenteeism[mesh] OR sick[tiab] OR sickness[tiab] OR “sick leave”[mesh]) AND (work*[tiab] OR workplace[mesh] OR employ*[tiab] OR job[tiab])

A complete list of the search strategies for the 5 databases are presented in a supplementary table S1, www.sjweh.fi/show_abstract.php?abstract_id=3819)

Study selection

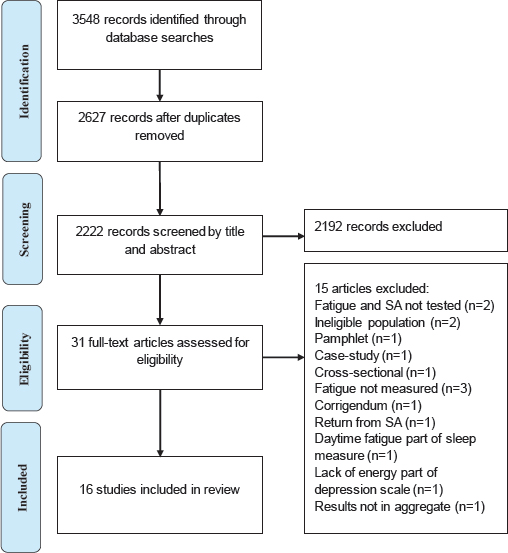

The primary search identified 3011 references. After removing duplicates, the reference list included 2222 studies. Two authors independently screened the titles and abstracts of the studies and retrieved 30 potentially relevant articles, which they then reviewed based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. Each article was evaluated independently, and disagreements were resolved by consensus; 15 studies were identified that were longitudinal in design. The second search included 405 new references after removing 132 duplicates. Following the same screening process, 1 study was identified and added to list, thus yielding a total of 16 studies. The PRISMA flow diagram illustrates the steps of the literature search to the final selection of the studies for the systematic review (figure 1).

Data extraction

The first author extracted data from the studies while the second author audited the data independently against the studies. Data extraction included: author, publication date, country, study design, follow-up period (years), sample size, sex, age, fatigue measurement, SA outcome, and specific variables (sleep, health and depression) that were accounted for in the adjusted final model. Data for study estimates when reported included adjusted odds ratio (OR), risk ratio (RR), hazard ratio (HR), rate ratio, and 95% confidence intervals (CI) as well as regression coefficients (β), and standard errors (SE). The data were used to depict visual representation of study findings using forest plots and to run meta-analyses. Our source of data was restricted to the published articles, thus no authors were contacted for additional information.

Risk of bias assessment

Study quality was scored using the Newcastle Ottawa criteria, with points for selection given to studies where selection of both fatigued and non-fatigued participants were drawn from the same population (1 point) and representative of the average employed adult in the community using a population-based sampling method (1 point). Ascertainment of fatigue was not scored as fatigue is a subjective phenomenon not amenable to objective ascertainment as required by the Newcastle Ottawa criteria. Measuring and controlling for prior history of sickness absence at study onset was given 1 point to offset selection bias. Comparability of fatigued and non-fatigued workers by design or analysis was assessed; the important factors of age and gender were consistently controlled in studies so points were given for occupational grade (or education as a proxy) (1 point) and doctor-diagnosed or validated survey of disease state (1 point). Points for outcome assessment were given for medically-certified absences, compensation databases, registries, or contemporaneously reported sickness absence to employer (ie, not retrospectively reported) (1 point); ≥6 months of follow up (1 point); and complete follow up or study retention ≥80% with loss to follow up adequately explained (1 point). The total possible score was 8 (see table 1). Two reviewers independently scored the quality of the studies and discrepancies were resolved by consensus. A detailed scoring using the modified Newcastle Ottawa scale is presented in a supplementary table S2 (www.sjweh.fi/show_abstract.php?abstract_id=3819).

Table 1

Characteristics of longitudinal studies on fatigue and sickness absence (SA) in the working population (N=16) [SA=sickness absence; SD=standard deviation; NOS=Newcastle Ottawa Scale assessment of risk of bias].

| Study | Country | Design Follow-up | Total N (% Men) | Age mean (SD) | Measures of fatigue | Measures of SA | Adjusted variables | NOS a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sagherian et al 2017 (36) | United States | Retrospective 1 year | 40 (0.0) | 30.90 (7.86) | Occupational Fatigue Exhaustion Recovery: chronic and acute fatigue | Registry-based absence Work shift: absent or present | Age, marital status, race, education, dependents, alcohol use, smoking, body mass index, sleepiness, sleep problems, health problems, depression, nursing experience, unit of practice, workload, shift type, second job, number of breaks | 6 |

| Roelen et al 2015 (31) | Netherlands | Prospective 1 year | 633 (62.0) | 44.4 (9.3) | Checklist Individual Strength: chronic fatigue | Registry-based absence High: ≥30 days (yes) High: ≥3 episodes | 5 | |

| Roelen et al 2014 (33) | Netherlands | Prospective 1 year | 633 (62.0) | 41.5 (9.6) | Checklist Individual Strength: chronic fatigue | Registry-based absence Long-term (medically-certified): ≥30 days | Age, gender, job type, work hours per week, years of employment | 6 |

| Roelen et al 2014 (34) | Netherlands | Prospective 1 year | 633 (62.0) | 41.5 (9.6) | Checklist Individual Strength: chronic fatigue | Registry-based absence Short-term: 1−7 consecutive days per episode Long-term: >7 consecutive days per episode Total number of SA episodes | Age, gender, job grade, history of SA | 5 |

| Roelen et al 2013 (35) | Norway | Prospective 1 year | 1506 (8.9) | Not mentioned as total sample | Chalder’s Fatigue Questionnaire: physical and mental fatigue | Self-reported absence High: >30 days (yes) |

Model 1: age, gender, marital status, children at home, coping Model 2: exercise, smoking, alcohol, caffeine use, body mass index Model 3: physical and mental health-related functioning, history of SA Model 4: nurse experience, work hours, shift schedule Model 5: job demand, job control, job support, role clarity, role conflict, fair leadership |

4 |

| Bültmann et al 2013 (7) | Denmark | Prospective 1 year | 6538 (49.0) | 42.6 (10.5) | SF-36 vitality subscale: general fatigue/energy | Registry-based absence Long-term: ≥21 days | Gender, age, cohabitation, children, occupational grade, survey method, smoking, alcohol use, physical activity, body mass index, physician-diagnosed disease, depressive symptoms, sleep disturbances | 8 |

| Roelen et al 2010 (29) | Netherlands | Retrospective 2 years | 470 (not mentioned) | 45.2 (9.8) | Health complaints scale: fatigue | Registry-based absence Short-term: 1−7 consecutive days per episode Medium-term: 8−42 consecutive days per episode Long-term: >42 consecutive days per episode | Age, gender, education | 5 |

| Akerstedt et al 2007 (37) | Sweden | Prospective 2 years | 8300 (~50.0) | Not mentioned for total sample | Tired and listless | Registry-based absence Intermediate-term: 14-89 days Long-term: ≥90 days | Age, gender, marital status, children at home, socioeconomic group, heavy physical work, twisted work posture, shiftwork, fulltime/part-time, job demands, low job control, overtime, disturbed sleep | 6 |

| De Croon et al 2005 (30) | Netherlands | Prospective 2 years | 755 (99.0) | 39.2 (9.5) | Trucker strain monitor subscales: work-related fatigue and sleeping problems. | Self-reported absence Total number of SA due to psychological health complaints: >14 days | 4 | |

| Bültmann et al 2005 (43) | Netherlands | Prospective 1.5 years | 6403 (83.0) | Men 41.6 (8.6) Women 37.2 (9.1) | Checklist Individual Strength: chronic fatigue | Registry-based absence Long-term: ≥42 days | Age, education, living alone, chronic disease | 8 |

| Mohren et al 2005 (40) | Netherlands | Prospective 0.67 years | 5531 (39.6) | Not mentioned for total sample | Checklist Individual Strength: chronic fatigue | Self-reported absence SA from common cold, flu-like illness or gastroenteritis (yes or no) | Age, gender, education, smoking, job demands, decision latitude, work situation, schedule, commitment, job satisfaction, executive function, job insecurity, chronic disease | 6 |

| Huibers et al 2004 (41) | Netherlands | Prospective 2 years | 2108 (75.0) | 40.6 (8.7) | Checklist Individual Strength: chronic fatigue | Registry-based absence Long-term: ≥42 days | Age, education, exhaustion, decision authority, skill discretion, supervisor support, gender, shift type, history of SA, fatigue complaints, health complaints, chronic diseases, sleep disturbances, self-rated health, life events, depressed/anxious mood, psychological distress | 7 |

| “Did you suffer from fatigue complaints in the previous 4 months?” If yes, fatigue causes: physical, psychological, and unknown attribution | ||||||||

| Janssen et al 2003 (39) | Netherlands | Prospective 0.5 years | 7495 (74.5) | 40.36 (8.86) | Checklist Individual Strength: chronic fatigue | Registry-based absence Short-term: 1−7 days Long-term: >42 calendar days | Age, education, gender, psychological job demands, decision authority, skill discretion, supervisor support and co-worker support | 7 |

| Andrea et al 2003 (42) | Netherlands | Prospective 1.5 years | 1271 (74.4) | Not mentioned for total sample | Checklist Individual Strength: chronic fatigue | Registry-based absence SA: no/short 1−7 days, 8-29 days, 30-89 days, 90-179 days, ≥180 days | Age, gender, education, health problems, job satisfaction, job demands, decision latitude, social support | 6 |

| Sluiter et al 2003 (23) | Netherlands | Prospective 1 year Prospective 2 years | N1=614 (22.0) N2=625 (not mentioned) | 39.36 (9.00 39.11 (10.12) | Need for Recovery: acute fatigue | Source of data not mentioned SA treated as continuous variable | Age, work hours per week, physical demands, mental/emotional demands, lack of decision latitude, lack of autonomy | 2 |

| De Croon et al 2003 (38) | Netherlands | Prospective 2 years | 526 (99.0) | 39.00 (9.40) | Need for Recovery: end-of-shift fatigue (i.e., acute fatigue) | Self-reported absence Total number of SA: >14 days | Age, marital status, education, history of SA, company size, job control, psychological job demands, physical job demands, supervisor job demands | 4 |

Statistical analysis

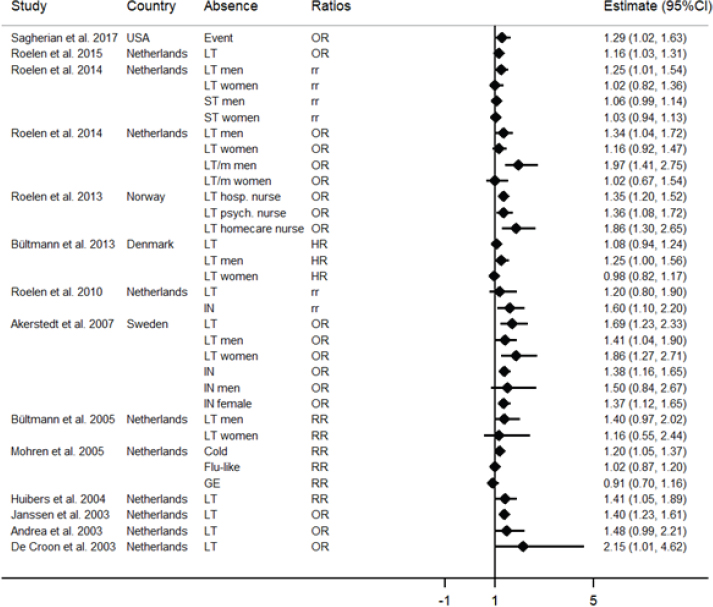

For the systematic review, we presented the results of the individual studies graphically using a forest plot (figure 2).

Figure 2

The forest plot represents the studies included in the systematic review. The estimates of 14 of 16 studies were possible to be shown graphically. The 33 estimates consisted of odds ratios (OR), rate ratios (rr), risk ratios (RR) and hazard ratios (HR). Sickness absences represent long-term (LT) or mental long-term (LT/m), short-term (ST), intermediate (IN) and related to cold, flu-like symptoms or gastroenteritis (GE).

For the meta-analysis, first we included studies with independent samples and studies that published data from the same cohort however with different time points and inclusion criteria. If studies were published using the same cohort and had identical study design and follow-up period, we included the study that was most similar in outcome with the rest of the included studies. Second, when a study provided estimates for regression models that were adjusted for different clusters of covariates, the estimate for the adjusted model with covariates similar to the rest of the studies were included. Third, when analyses were stratified by gender, the risk estimates for men and women were included separately in the meta-analysis. Fourth, results reported as regressions coefficients and SE were transformed to OR and 95% CI using an online calculator (www.danielsoper.com/statcalc/calculator.aspx?id=26) whenever possible. Fifth, studies that did not report the duration of SA such as long-term or short-term were not included in the meta-analysis.

Using STATA 14.2 software (StataCorp, College station, TX, USA), we conducted random-effects meta-analysis using the metan command. Random-effects (DerSimonian & Laird method) models were appropriate and best fit to data considering the methodological variations between the studies (27). Risk estimates (OR, HR, RR) and 95% CI were log transformed and random-effects meta-analyses with the eform option were conducted to obtain pooled estimates of the relationship between fatigue and SA (long-term and/or short-term). Also, random-effects meta-analyses were conducted for men and women separately (depending on available data). We note that rate ratios were excluded when pooled effects were estimated (one study only). The heterogeneity across the studies was assessed by I2 statistics. An I2 value of 0% indicates no heterogeneity, 50% is considered moderate and ≥75% indicates high heterogeneity (28). Analyses with P<0.05 were considered significant. Sensitivity analyses were conducted by country and risk type to identify any possible sources of heterogeneity. Publication bias was assessed by the funnel plot (log estimates plotted against SE of log estimates) and Egger’s test.

Results

Study selection and methodological rigor

The PRISMA flow diagram illustrates the steps of the review process and the final selection of the 16 longitudinal studies (figure 1). At first, 31 studies were identified and the full-text articles were reviewed. Of these, 15 were excluded for a number of reasons such as cross-sectional design, ineligible/patient population, and absence of fatigue measurement, and 2 were excluded because fatigue was measured as part of a sleep and depression scale. The 16 eligible studies were published between 2003 and 2017 with the majority being prospective in design and from Netherlands (12 studies) followed by Scandinavia (3 studies) and United States (1 study). Participants represented diverse working populations of white- and blue-collar workers, insurance workers, truck drivers, nurses, and eldercare employees. The primary aim of most studies was to examine the relationship between baseline fatigue and future SA. However, one study measured fatigue as part of a health questionnaire (29). Two other studies focused on establishing the criterion validity of an instrument that consisted of work-related fatigue and sleeping problems subscales in relation to future SA (30) and whether fatigue contributed significantly to a SA prediction model in risk reclassification analyses (31).

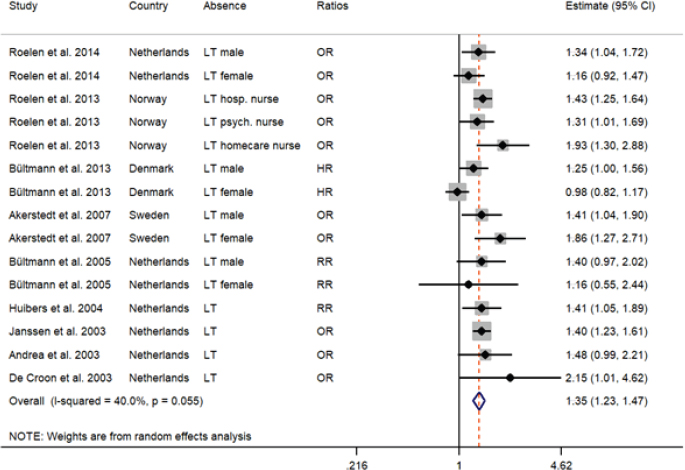

Figure 3

The forest plot represents the meta-analysis of the prospective association between fatigue and long-term (LT) sickness absence (9 studies providing 15 estimates). The risk estimates under the ratios column are odds ratios (OR), relative risk (RR) and hazard ratios (HR).

The Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to assess risk of bias. Studies ranged from 2−8 on a 0−8 point scale. Considering selection, this grading schema favored the generalizability of population based samples such as the Maastricht Cohort Study over occupation-specific samples of truck drivers or nurses. Although prior SA is known to be a predictor of future SA (32), this factor was not measured or controlled for in 6 studies. For comparability, the authors selected occupational grade/education, and presence of a disease state as factors to be made comparable by design or analysis. These items accounted for a lessening of NOS scores including the presence of disease at baseline (6 studies), occupational/educational grade (11 studies). The measurement of SA was subjectively recalled by participants in 5 studies, otherwise register-based objective data were used. All studies were of ≥6 months duration. Study retention rates were >80% in all but 4 studies (see supplementary table S2 for detail).

Study characteristics

A descriptive summary of the 16 studies is presented in table 1. Two studies provided a conceptual definition of fatigue as “an overwhelming sense of tiredness, lack of energy, and a feeling of exhaustion associated with impaired physical and/or cognitive functioning” (33, 34). Most studies measured fatigue either as a unidimensional or multidimensional construct. Six different instruments were used: (i) the Checklist Individual Strength (CIS) measured chronic fatigue and consisted of fatigue severity, reduced motivation and concentration, and decreased physical activity dimensions; (ii) the Need for Recovery scale (NFR) measured end-of-shift or acute fatigue; (iii) the Chalder’s Fatigue Questionnaire (CFQ) measured physical, mental and total fatigue; (iv) the Occupational Fatigue Exhaustion Recovery (OFER 15) scale measured chronic fatigue, acute fatigue and intershift recovery concurrently; and (v) as part of the Short Form (SF)-36, the vitality subscale measured an individual’s own perception of fatigue and energy level and 6) specific to truck drivers, the Trucker Strain Monitor measured work-related fatigue and sleeping problems separately. In most studies, evidence of reliability and adequate information about the validity of the scales in the general workforce were reported.

Regarding SA, a conceptual definition was not present in most studies, a weakness commonly reported in the literature (26). In four studies, SA was defined as “an absence or paid leave from work because of work or non-work related illness or injury” (31, 33–35), and in one study as “failure to report for scheduled work” (36). As shown in table 1, SA was measured by the duration and frequency of SA episodes with the duration of absences varying across countries. This variation in cut points that indicates long-term is related to legislation and social insurance systems for paid leaves unique to each country, whether SA was self- or medically-certified, as well as prior research and study objectives. Long-term SA was defined as the number of consecutive or cumulative absence days lasting for 14, 21, 30, 42, and ≥90 days. In two studies, long-term SA was also defined as episodes: >7 consecutive days over one year or >42 days over two years (29, 34). Short-term SA was measured in two studies with a duration lasting 1–7 days. Two studies had SA defined as medium (8–42 days) or intermediate (14–89 days) in duration (29, 37). SA data were objective in nature extracted from company-based and national insurance registries, while two studies used self-reports with a recall period of 12 months (35, 38) that raises concerns for recall bias.

Descriptive summary by country

Figure 2 shows a graphic representation of the 14 studies (providing 33 estimates) included in the systematic review (2 studies could not be presented graphically). Overall, 14 of the 16 studies reported a significant relationship between fatigue and SA in the working population. The follow-up period in these studies ranged from six months to two years. There was more supportive evidence on the relationship between chronic fatigue and long-term SA where most studies focused on this outcome. Gender influenced the relationship between fatigue and SA with an increased risk for long-term SA in men than women.

Netherlands. Three studies with different SA measures were published using an identical insurance dataset of white-collar employees who were invited to perform an occupational health checkup. The results were similar where after 1-year of follow-up, men with high chronic fatigue had an increased risk for the number of long-term (>7 days) and total SA episodes (34). Men with high chronic fatigue and fatigue severity were at higher odds for medically-certified and mental long-term (≥21 days) SA than those with low chronic fatigue (33). When evaluating the contribution of fatigue in a SA prognostic model, for every 10 point increase in chronic fatigue scores, insurance employees were 16% and 14% more likely to have high SA (≥30 days) and high SA episodes (≥3) (31). Also, fatigue measured as a subjective health complaint was associated with intermediate-SA episodes in blue- and white-collar workers after two years of follow-up (29).

In 1998, the Maastricht cohort study was initiated to explore the phenomenon of prolonged fatigue over time and develop preventive measures in the working population. A total of 12 161 employees from 45 companies participated and were followed over a period of three years. Five studies were published on the relationship between fatigue and SA that differed by inclusion/exclusion criteria and follow-up period. The first study followed participants over six months and found that chronically fatigued workers had quicker onset to first short-term (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.81–0.90) and first episode (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.81–0.88) of SA, and significantly increased the odds for long-term (>42 days) SA (39). The second study reported an increased risk for SA due to common cold but not flu-like illness or gastroenteritis in employees who experienced elevated chronic fatigue over eight months of follow-up (40). The third study focused on 1681 fatigued employees and found that physical attribution of fatigue at baseline increased the risk of long-term SA over a period of 18 months (41). Contrary to these results, the remaining two studies reported no significant relationship after adjusting for health problems. In the fourth study that included 1271 employees who visited the occupational physician and/or general practitioner in relation to work, chronic fatigue did not predict long-term SA of any duration (1–3, 3–6, ≥6 months) when compared to no/short-term SA after adjusting for health problems and the psychosocial work environment (42). Similarly, the fifth study reported that being a case of chronic fatigue (CIS scores >76) alone did not significantly predict long-term SA after accounting for chronic diseases after 18 months of follow-up (43).

A few studies from Netherlands focused on end-of-shift fatigue (ie, acute fatigue) that was measured by the NFR scale. One study showed that acute fatigue increased the number of SA days in hospital nurses (β=0.19, P<0.001) and truck drivers (β=0.11, P=0.021) (23). Two other studies were published using the same dataset on Dutch truck drivers with data on the NFR scale, TSM subscales and self-reported SA. In the first study, truck drivers with high NFR scores had double the odds of reporting SA (>14 days) after two years of follow-up (38). In the second study, baseline TSM work-related fatigue scores significantly correlated with SA due to psychological health complaints (Spearman rho 0.21, P<0.01) after two years of follow-up (30).

Scandinavian countries. Three studies from Scandinavia showed that fatigue significantly predicted long-term SA in the general workforce that consisted of white- and blue-collar workers and healthcare providers. From Denmark, the results showed that fatigue increased the risk of long-term SA (≥21 days) in men but not women after 1-year of follow-up (7). From Norway, the study focused on nurses from hospital, psychiatric and nursing home care settings and found that elevated physical and total fatigue increased the odds of self-reported high SA (>30 days) after 1-year of follow-up (35). In a national study from Sweden, fatigued workers were more likely to have intermediate (14–89 days) and long-term (≥90 days) SA after a period of two years. When stratified by gender, only fatigued women were more likely to have intermediate SA, whereas both fatigued men and women were more likely to have long-term SA (37).

United States. The most recent study was from the US where 40 female hospital nurses were followed over 12 months. This period resulted in 5745 work shifts and 312 absences. Accounting for multiple covariates and effects of time, the results showed that acute fatigue measured at baseline and not chronic fatigue significantly predicted SA (36).

Meta-analysis

Nine prospective studies that provided 15 estimates were eligible and included in the meta-analysis of which four studies were stratified by gender (34 353 participants included). The duration of SA in these studies were of long-term. Figure 3 presents the forest plot of study-specific estimates and 95% CI. The pooled estimate was 1.35 (95% CI 1.23–1.47). This result shows that baseline fatigue increased the risk of long-term SA by 35%. The I2 was 40% indicating low-moderate level of heterogeneity. Sensitivity analyses were conducted by country and risk type and the results were similar. The heterogeneity was primarily attributed to the study from Denmark that reported hazards ratios (see figures S1 and S2, www.sjweh.fi/show_abstract.php?abstract_id=3819).

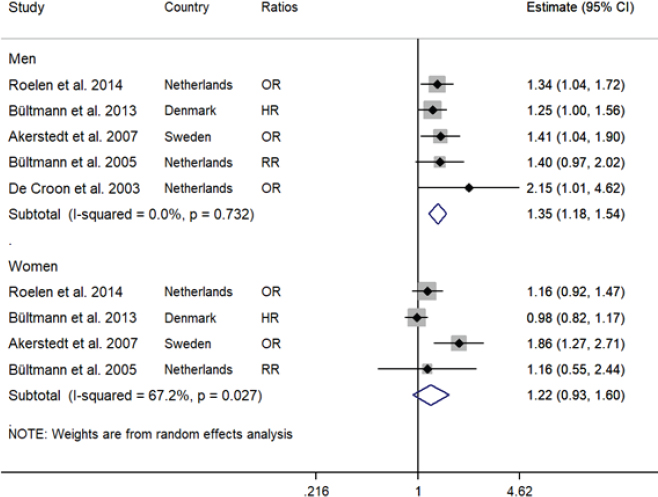

We also conducted meta-analyses for men and women. For men, the meta-analysis included five studies (1 study had 99% male). The pooled estimate was 1.35 (95% CI 1.18–1.54) with no evidence of heterogeneity (I2 =0%). For women, the meta-analysis included four studies and the pooled estimate was 1.22 (95% CI 0.93–1.60) but statistically not significant. Heterogeneity was considered moderate-high with an I2 of 67.2% (figure 4). These results indicate that baseline fatigue increased the risk of long-term SA by 35% in men only.

Figure 4

The forest plot represents the meta-analysis of the prospective association between fatigue and long-term sickness absence in men (N=5) and women (N=4). The risk estimates under the ratios column are odds ratios (OR), relative risk (RR), and hazard ratios (HR).

Publication bias was assessed by the funnel plot which showed some asymmetry to the right (figure 5). However, the Egger’s regression test showed no sign of publication bias where the intercept was not significant (P=0.292).

Discussion

This systematic review followed by the meta-analysis provided supportive evidence for the relationship between fatigue at baseline and future SA in the general workforce. Most studies measured fatigue as chronic in nature and SA of long-term (figure 2). Based on nine prospective cohort studies that were mostly of high quality, the meta-analysis showed that fatigue was significantly associated with 35% increased risk for long-term SA in the general workforce. This pooled estimate was stronger in men (35%) than women (22%) and was statistically significant in men only.

The duration of long-term SA varied across the studies with >14, 21, 42, 90, and even 180 days that together with different follow-up periods may have influenced the magnitude of the relationship with fatigue. Most researchers aligned these cut points according to their country’s social insurance systems for employee benefits and paid sick leaves. In this review, research on the relationship between chronic fatigue and long-term SA was predominantly from the Netherlands where Dutch employees who are on SA are compensated by their employers for up to two years. Thus, addressing chronic fatigue can help lower the duration of SA episodes and decrease the enormous financial burden associated with absenteeism. We note that only one study originated from the US, which contrary to European countries has less generous SA compensation benefits. It is probable that this condition may lead to frequent short-term SA in fatigued employees or even presenteeism where fatigued employees present to work while being sick (44), however more research is needed.

It is also important to note that fatigue measurement remains a challenge for occupational researchers in the absence of an agreed upon definition, thus leading to the use of different fatigue instruments or single item questions. In the meta-analysis, this measurement heterogeneity was highly evident and resulted in inconclusive evidence with regards to chronic fatigue but supported the measurement of fatigue as a construct. Despite this challenge, fatigue instruments such as the CIS for chronic fatigue, CFQ for physical, mental and total fatigue, and the NFR for end-of-shift acute fatigue elucidate a better understanding of workers’ fatigue experiences and their influence on long-term SA (34, 35, 38). Although more research is needed in this area, findings such as chronic fatigue and its physical intolerance and reduced concentration or motivation dimensions in workers (34) are highly informative and can help researchers in designing fatigue interventions that address specific areas of fatigue in the workplace.

Another factor to consider when developing fatigue intervention programs is gender differences with respect to fatigue published in the literature. Fatigue has been reported to be more common and to be present at higher levels in women than men (18, 45). In the Bensing et al study (45), whereas most of the fatigue in women was attributed to psychological problems, family responsibilities, biological complaints and employment, fatigue in men was related to more severe or chronic problems. This trend is similar in SA where the incidence is higher in women than men. However, the duration of SA is more short-term in women and long-term in men (46). Despite an increased risk of 22%, the relationship between fatigue and long-term SA did not reach significance in women (four studies) in our meta-analysis. In addition to having small number of studies, this may be related to the type of fatigue (ie, chronic versus acute) or to occupation/job type where men held higher grade positions with higher cognitive demands than women in the samples under study. However, two studies that were not part of the meta-analysis in women found that physical fatigue (91% women; OR 1.36, 95% CI 1.24–1.50) and acute fatigue (100% women; OR 1.29, 95% CI 1.02–1.63) significantly increased the likelihood of SA in female nurses (35, 36). It is probable that this type of fatigue is elevated because of family responsibilities and social demands during non-work hours, in addition to the demands of work. Thus, more research is needed in profiling differences in fatigue experienced by male and female workers and in examining its relationship with the duration of SA.

One area that remained under-reported in most of the studies was the assessment of sleep in workers (three studies only) (7, 37, 41), a limitation that may be related to secondary data. Often sleep, a biological need is jeopardized because of shiftwork, economic pressures and second jobs, and family responsibilities that lead to elevated fatigued states (47, 48). Sleep disorders such as sleep apnea and insomnia, which are commonly reported in workers (49), are also related to SA (36, 50). This stressful synergy between work-related fatigue and sleep deficiency/sleep disorders creates a platform for developing physical and/or psychological health problems (51) and increases the risk of absenteeism from the workplace. Consequently, the inclusion of sleep disorders screening and sleep health promotion for workers becomes vital as researchers and organizational leaders seek ways to develop effective fatigue mitigation strategies in the workplace.

Strengths and limitations

Overall, the included studies had a number of strengths related to design, sample size, use of fatigue instruments with good reliability and validity, application of statistical rigor and decreased risk for recall bias. Moreover, most of the prospective cohort studies included in the random-effects meta-analysis were of high methodological rigor. The longitudinal design established the temporal sequence of events where fatigue at baseline predicted future SA. Most studies had a large number of participants from multiple sites that were representative of the average worker in the community. The possibility of recall bias was minimal since most researchers used SA data from registries, which gives validity to the data and the findings.

On the other hand, we also acknowledge a number of limitations that should be addressed in future research. One limitation was related to selection bias in most studies because of low response rates at baseline during participant recruitment. However, the large-scale studies addressed this limitation by non-respondent analyses when data were available (34, 38, 40, 41, 43). It is also probable that selection of sub-populations based on certain conditions related to fatigue such as employees with an infection (40), employees who are severely fatigued (41) or employees who visit the occupational physician possibly due to work-related problems (42) may lead to collider bias and result in biased estimate of the relationship between fatigue and SA, however this effect cannot be determined.

Also, external validity in a few studies was jeopardized where the data were collected from one institution (33, 34, 36). While the majority used SA company records and registries, the risk for recall bias was still present in four studies (30, 35, 38, 40). Depending on the duration of personal recall, self-reporting of SA can either under or overestimate the results. In some studies, detection bias was possible where fatigue was measured as a single item. This may cause either under or overestimation of fatigue levels, thus leading to possible misclassification between fatigued and non-fatigued subgroups.

Based on their study objectives, most statistical models adjusted for personal and work variables that gave confidence in the results. Whereas it is not possible to control for all confounders and risk for model overfitting or even collider bias, variables such as having second jobs, overtime, shiftwork characteristics, sleep, depressive symptoms, and health problems when applicable are important to be factored into the relationship of fatigue and SA. In two Dutch studies, the relationship between fatigue and long-term SA lost significance when adjusted for chronic diseases (41, 42). This effect may be related to progression of disease where workers can experience a cluster of symptoms including fatigue which makes it difficult to separate from work-induced fatigue. Thus, exploring the role of fatigue as a mediator rather than an exposure variable becomes more appropriate in some studies.

On a final note, the majority of the studies used either Poisson regression or Cox proportional hazards models in analyzing SA data, and only one study used random intercept models to account for nesting effects. In a simulation study, Christensen and colleagues (52)used in addition to the two methods, frailty models (ie, random effects model for time-to-event data) that accounted for the dependence between events and person effects when analyzing SA data. The results showed that Cox proportional hazards followed by Poisson regression models underestimated the true effect sizes when compared to frailty models where the heterogeneity between subjects was accounted for (52). It is conclusive that random effect models can yield better risk estimates (52), however the statistical approach is dependent on the study objectives and the type of available SA data.

Concluding remarks

Based on our results, we conclude that fatigue in workers significantly increases the risk of long-term SA by 35%. Work-related fatigue is a subjective experience with physical, mental, emotional, and behavioral components. Thus, we recommend the use of psychometrically sound measures to better capture this complex phenomenon which will subsequently help in tailoring SA management strategies and facilitate employees’ quick return to the workplace.

Most research in this review has examined the relationship between fatigue and long-term SA, while a few studies have focused on short-term SA. Frequent short-term absences from work are also common and costly and can impact the work environment and team morale. Whereas chronic fatigue is associated with long-term SA, it is likely that acute fatigue, which is primarily the byproduct of day-to-day work stressors and transient due to rest and sleep is related to short-term SA. More research is needed to explore this hypothesized relationship where only two studies in the systematic review have measured acute fatigue in relation to long-term SA in truck drivers (38) and SA events but without differentiating between long- and short-term durations in hospital nurses (36).

From the Netherlands, Huibers et al (41) found that chronically fatigued employees had periods of fatigue remissions and relapses when followed over the same time frame as SA. One potential area of future research is to explore the patterns of acute and chronic fatigue and SA together over time and identify the triggers related to chronic fatigue development or relapses. Based on allostatic load theory, researchers hypothesize that prolonged exposure to acute fatigue leads to the development of chronic fatigue. Since SA suggests a need to recover, examining its mediating or moderating role in terms of frequency and duration can be of great importance. For example, employers or occupational therapists can strategically prescribe off-days to high-risk employees and prevent a cycle of chronic fatigue relapse and higher and longer duration of SA.

Finally, our meta-analysis showed a significant association between fatigue and long-term SA in men only. More studies are needed to better understand the differences in this relationship between men and women in different working groups. To date, there is no generic approach to reducing SA where the outcome is multi-factorial in nature. Occupational health interventions such as consultation with healthcare services or occupational physicians have shown to be effective in decreasing the duration of SA in workers who are at high-risk for long-term SA (53, 54). However, gender-specific approaches to managing work-related fatigue levels may help further in reducing both the frequency and duration SAs, however more research is needed in this area.