Premature exit from paid employment is a serious concern at both the individual and societal level. On the individual level, exit from paid employment might not only increase the risk of financial and social problems, it might also increase the likelihood of experiencing health problems (1). On the societal level, there is a need to increase work participation and sustain a productive workforce because of decreasing birth rates and increased life expectancy in most industrialized countries (2). Therefore, many countries are developing policies to stimulate labor force participation, particularly to encourage older workers to remain at work longer. In order to develop successful interventions to reduce exit from the labor force, insight into the main determinants of exit from paid employment is needed.

From previous research it is known that poor health plays a role in exit from paid employment, particularly due to disability pension (3–6). Several studies also reported that workers with a poor health are more likely to become unemployed (4, 7–11) and, to a smaller extent, to retire before the statutory retirement age (4, 11, 12).

Unhealthy lifestyle behaviors as well as physical and psychosocial work demands might also play a role in exit from paid employment (10). However, the evidence concerning these factors is less consistent. In a cross-sectional analysis, an unhealthy lifestyle was associated with unemployment and early retirement (13). In longitudinal studies, a slightly increased risk of early retirement was found among obese workers and workers with high physical and psychosocial work demands (4, 9, 14). Smoking and obesity have been found to be a determinant of disability pension (6, 15–18). Work-related characteristics underlying Karasek’s job demand–control model (19) and Siegrist’s effort–reward imbalance model (20) seem to predict exit from paid employment (4).

Determinants of exit from paid employment might differ between the main pathways of leaving the labor force, particularly between the involuntary (ie, disability pension, unemployment) and more voluntary routes (ie, early retirement) of exit from work. In the current study, we aim to get insight into the role of health, health behaviors, and work characteristics on exit from paid employment due to disability pension, unemployment, and early retirement. Hereby, determinants of different routes of exit from work can be studied simultaneously. The hypothesis is that different factors play a role in different routes of exit from work. We hypothesize that poor health and unhealthy behaviors (particularly obesity and smoking) and unfavorable work characteristics (particularly low job control) will increase the likelihood of ending paid employment due to involuntary routes of exit from work.

Methods

Study design and study population

Determinants of exit from paid employment were investigated in a longitudinal study with a 4-year follow-up. The study population consisted of participants of the Survey of Health, Ageing, and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). SHARE is a longitudinal study that aims to collect health, social, and economic data on the population aged ≥50 years; it started in 2004 and 2005 in 11 European Union countries (Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, France, Italy, Spain, and Greece) (21). In the participating SHARE countries, the institutional conditions with respect to sampling were so different that a uniform sampling design for the entire project was not feasible. Different registries at the national or local level were used, enabling stratification by age. The sampling designs varied from simple random selection of households to complicated multistage designs.

Information from three waves of data collection was used for the analyses. The first wave was collected by interviews in 2004 and 2005. The overall household response across the 11 SHARE countries was 62%, although substantial differences among countries were observed (21). The available dataset from the first wave of data collection (SHARE release 2.4.1) contains 28 517 respondents, with 13 429 (47%) respondents aged between 50 years and the country specific-retirement age. For 118 individuals, employment status was unknown, resulting in a study population of 13 311 individuals, of which 7233 (54%) had paid employment at baseline. Of these 7233 respondents, 1748 (24%) did not participate in the second (2006/2007) or third waves (2008/2009), and an additional 456 individuals were excluded because of conflicting (N=220) or missing (N=236) information on work status, resulting in 5029 employees or self-employed respondents aged ≥50 years with baseline and follow-up information on work status. For 106 respondents (2%), information on potential determinants of exit from work was missing. Finally, 4923 employed respondents aged ≥50 were included in the analyses.

Labor force participation

The primary outcome measure in this study is self-reported work status. In the second wave of data collection, a single question asked: “In general, which of the following best describes your current employment situation? Retired, employed or self-employed, unemployed and looking for work, permanently sick or disabled, homemaker, other”. Furthermore, the month and year of exit were asked. In the third wave, a life-course approach was used and all periods of paid employment and exit from paid employment were assessed by the question: “Which of these best describes your situation after you left your last job?”. In case of exit from paid employment, the year of exit was asked.

Paid employment includes all individuals who (i) worked until they reached the statutory retirement age or (ii) were still at work at the end of the follow-up period. The disability pension category includes individuals stating they are permanently sick or disabled. The unemployed category includes those individuals who became unemployed from their last job before they reached the statutory retirement age. Early retirement is defined as self-reported retirement before the statutory country-specific retirement age. An overview of country-specific retirement ages at baseline is presented in table 1. The category “other” includes persons who stopped working during follow-up due to reasons other than disability pension, unemployment, or retirement. The analysis is restricted to the first route of exit from paid employment and does not take into account re-entering paid employment. Most workers who exited work remained out of the labor force since it has been shown that about 20% of those who became unemployed returned to paid employment during the follow-up, and corresponding figures for disability pension and early retirement were close to zero (22). In case of multiple events, only the first event was considered. When multiple events took place at the same point in time, the following hierarchy was used: (i) disability pension, (ii) unemployment, (iii) other events, or (iv) early retirement.

Health and health behaviors

Self-perceived health was measured, using a 5-point scale, asking “Would you say your health is…” Answers ranged from “excellent” to “very poor”. Poor health was defined as “less than good”. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing body weight in kilogram by the square of body height in meters. BMI was categorized into normal weight (<25 kg/m2), overweight (≥25–<30 kg/m2), and obese (≥30 kg/m2) (21). Physical activity was measured with separate questions on regular participation in moderate and vigorous intensity activities by asking “How often do you engage in activities that require a low or moderate level of energy such as gardening, cleaning the car, or doing a walk?” and “How often do you engage in vigorous physical activity, such as sports, heavy housework, or a job that involves physical labor?”. Answers were rated on a 4-point scale ranging from “more than once a week” to “hardly ever, or never”. Those who reported moderate or vigorous physical activity less than once a week were considered to have a lack of physical activity. Smoking status was measured with a single question and categorized into three categories (non-smoking, ex-smoker, and current smoker) (21). Excessive alcohol use was defined by an alcohol consumption of >2 glasses of alcohol beverages ≥5 days a week in the past 6 months by asking “During the last 6 months, how often have you had >2 alcohol drinks in a single day?” (21).

Work-related characteristics

Physical work demands were measured using a single question: “My job is physically demanding. Would you say you strongly agree, agree, disagree or strongly disagree?” (23). Those individuals who (strongly) agree were considered to have a physically demanding job. Psychosocial work-related characteristics were assessed by a short battery of items derived from the Job Content Questionnaire on the demand–control model (24) and the effort–reward imbalance model questionnaire (23). All items were measured on a 4-point scale ranging from 1=strongly agree to 4=strongly disagree. Time pressure was measured using a single item: “I am under constant time pressure due to a heavy workload. Would you say you strongly agree, agree, disagree or strongly disagree?” (23). Those individuals who (strongly) agree were considered to have a high time pressure. Job control was measured by using the sum score of two items: (i) “I have very little freedom to decide how I do my work” and (ii) “I have an opportunity to develop new skills” (24). Country-specific median values were used to define a lack of job control. Rewards were measured by using the sum score of five items addressing support, recognition, salary/earnings, job promotion prospects, and job security (23). Country-specific median values were used to define a lack of rewards. The job demand–control model was defined as the combination of the efforts and control items, using the country-specific median values distinguishing four groups: high control and low demands, high control and high demands, low control and low demands, and high control and low demands. Effort–reward imbalance was defined as the country-specific upper tertile of the ratio of the sum score of the effort items and the sum of the reward items, both adjusted for the number of items.

Demographics

In the interview, sex, birth month and year, educational level, and marital status were asked. The highest level of education was coded according to the 1997 International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED-97) and categorized into low (pre-primary, primary, and lower secondary), intermediate (upper secondary) and high (post secondary) education. Marital status was used to categorize individuals into those who were living with a spouse or partner in the same household (cohabitation) and those living alone.

Statistical analysis

In order to calculate rates of exit from paid employment, the number of events were expressed by person-years at risk in the study population and presented as events per 1000 person-years. Descriptive statistics were used to present country-specific information on labor force participation and general characteristics of the study population.

The effect of poor health, unhealthy behaviors, and unfavorable work characteristics on labor force exit due to unemployment, disability pension, and early retirement was analyzed with Cox proportional hazards regression analyses. For each pathway out of paid employment, the event was compared with the population who stayed at work until the end of follow-up or until they reached the statutory retirement age. An individual was censored at the moment the country-specific statutory retirement age was reached, when the individual was lost to follow-up, or at the end of the follow-up period. A random intercept was used to allow the baseline hazard function to differ between countries (25). The proportional hazards assumption was evaluated using time-dependent variables. None of the variables included in the analyses violated the proportional hazards assumption.

First, univariate relations were explored after adjustment for sex, age, educational level, and cohabitation status. All variables that were statistically significantly (P<0.05) related with a pathway of exit from paid employment were investigated in multivariate analyses. In order to increase the comparability between the models for the different pathways of exit from paid employment, any variable with a statistically significant relation with one pathway in the univariate analyses was also included in the multivariate model for the other pathways. A hazard ratio (HR) greater than one indicated an increased likelihood of labor force exit. The statistical analyses were carried out with IBM SPSS Statistics version 20 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

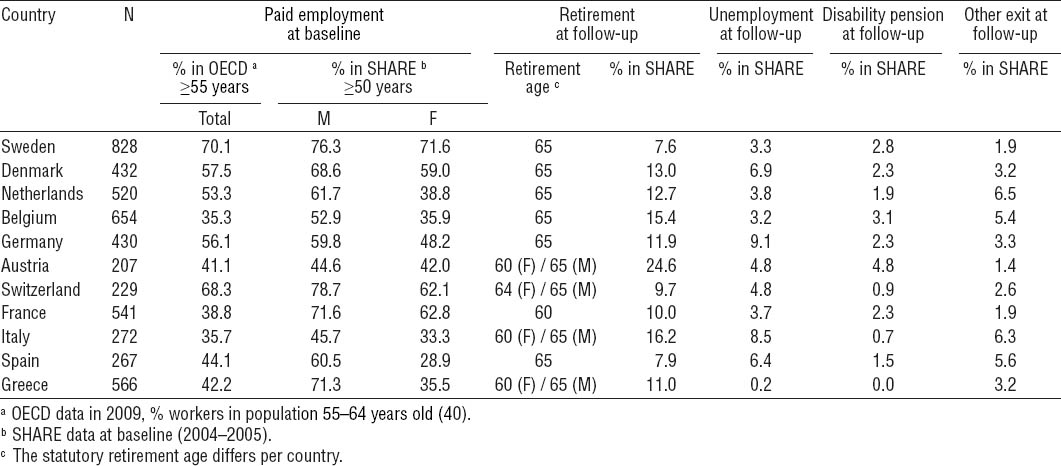

The study population consisted of 4923 employees with a follow-up time of 16 550 person-years. In total, 22% of the workers exited the workforce (66.0 per 1000 person-years). Most of the workers left paid employment because of early retirement (12%, 35.6 per 1000 person-years), followed by unemployment (4%, 13.2 per 1000 person-years). A less frequent pathway of exit from paid employment was due to disability pension (2%, 6.2 per 1000 person-years). Four percent left the labor force through other pathways (11.0 per 1000 person-years), in most cases due to becoming a homemaker. Table 1 shows considerable differences in labor force participation and pathways of exit between the participating countries. The proportion of workers in paid employment corresponded strongly with the reported national figures on labor force participation (Pearson’s r=0.73, P=0.01). On the country level, the proportion of exit due to disability pension correlated positively, although non-significantly, with the proportion of exit due to early retirement (Pearson’s r=0.57, P=0.07). Non-significant and weak correlations were found between the other pathways of exit and labor force participation (Pearson’s r<0.30).

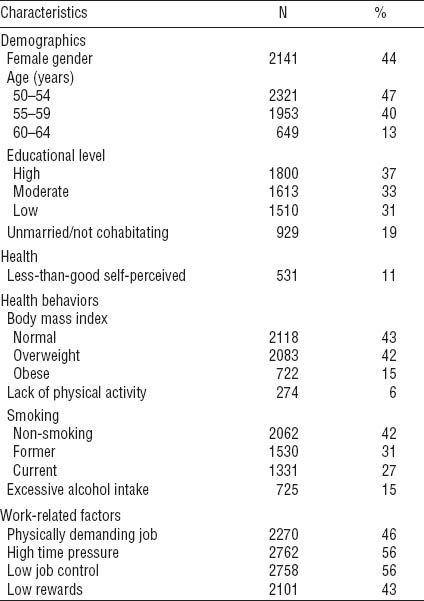

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the study population. The mean age of the study population was 55.2 years [standard deviation (SD) 3.5 years], with more male than female respondents. Older individuals and participants with a low educational level were more likely to exit from work due to disability pension, unemployment, and early retirement. Eleven percent of the participants had a less-than-good self-perceived health, and the mean BMI was 26.1 kg/m2 (SD 4.1 kg/m2). Poor health, a lack of physical activity, obesity, and all work characteristics were modestly interrelated (Pearson’s r<0.20).

Table 2

Individual, health, and work characteristics among N=4923 employed individuals in Europe at baseline.

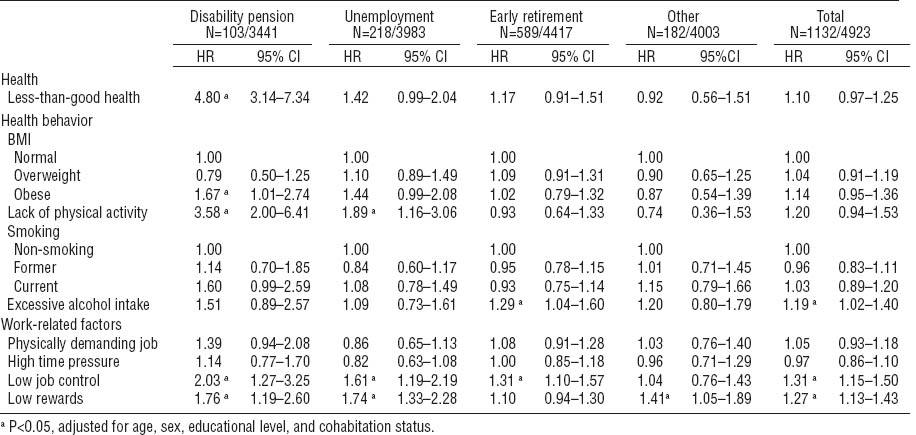

Individuals with a poor health, obesity, and a lack of physical activity had a higher risk of exit from paid employment through disability pension, and, almost statistically significantly, through unemployment after adjustment for sex, age, educational level, and cohabitation status (table 3). No statistically significant relations were found between these factors and early retirement. Excessive alcohol intake was related with early retirement. Of all studied work characteristics a lack of job control showed the highest increased risk for all three pathways of exit (HR 1.31–2.03), followed by low rewards (HR 1.10–1.76). Having physical job demands was not found to be related with exit from work after adjustment for demographics. Those workers with a low job control in combination with high demands (data not shown) were more likely to exit from paid employment (job demand–control: disability pension: HR 2.88, 95% CI 1.50–5.50; unemployment: HR 1.32, 95% CI 0.89–1.96, early retirement HR 1.25, 95% CI 0.99–1.58), but the strength of the relation was comparable with the influence of low job control only. A combination of high efforts with low rewards did not lead to higher HR than the single effects of low rewards on exit from paid employment (effort–reward imbalance: disability pension: HR 1.53, 95% CI 1.03–2.26; unemployment: HR 1.49, 95% CI 1.14–1.95, early retirement HR 0.99, 95% CI 0.83–1.18).

Table 3

Cox proportional hazard analyses on the influence of health, health behaviors, and work characteristics among employed persons on the likelihood of exit from paid employment during a follow-up period of 4 years after adjustment for demographics. All analyses adjusted for sex, age, educational level, and cohabitation status. [BMI=body mass index; HR=hazard ratio; 95% CI=95% confidence interval]

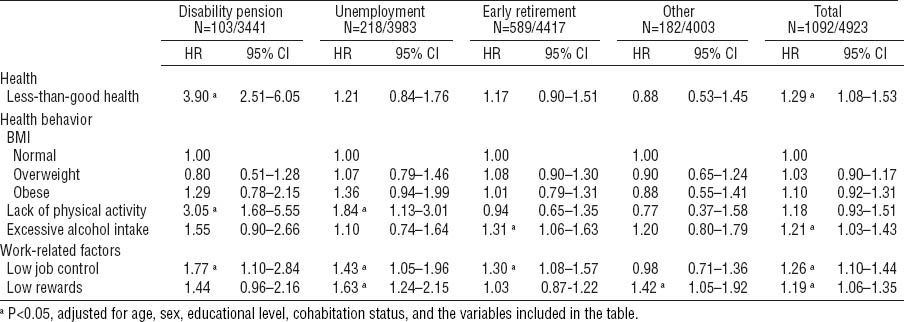

The univariate analysis shows that poor health is an important determinant of exit through disability pension (HR 4.80, 95% CI 3.14-7.34), but adjustment for lifestyle (HR 4.33, 95% CI 2.80-6.69) and work (HR 3.90, 95% CI 2.51-6.05) factors attenuated the strength of the relation (table 4). The relation between a lack of physical activity with disability pension and unemployment remained statistically significant, whereas the increased risk of obesity on these pathways decreased substantially after adjustment for demographics and self-perceived health. A lack of job control showed the highest increased risk for all three pathways of exit (HR 1.30–1.77), and a lack of rewards was related with unemployment (HR 1.63, 95% CI 1.24-2.15). These associations between psychosocial factors and exit from paid employment were attenuated after adjustment for demographics and self-reported health.

Table 4

Multivariate cox proportional hazard analyses on the influence of health, health behaviors, and work characteristics among employed persons on the likelihood of exit from paid employment during a follow-up period of 4 years. [BMI=body mass index; HR=hazard ratio; 95% CI=95% confidence interval]

Discussion

Poor health, unhealthy behaviors, and unfavorable work characteristics played a role in exit from paid employment, but their relative importance differed by pathway of labor force exit. Poor health increased the risk of disability pension, but was not related to early retirement. A lack of physical activity was a determinant of disability pension and unemployment. A lack of job control increased the likelihood of exit from paid employment through disability pension, unemployment, and early retirement.

This study investigated the effects of poor health on different pathways of exit from paid employment. It was hypothesized that poor health is an important risk factor for exit by the involuntary routes of disability pension and unemployment. In the univariate analyses, poor health was related to disability pension and with borderline significance to unemployment, and not to early retirement, which can be seen as a more voluntary pathway of exit from paid employment. The relation between poor health and disability pension is in agreement with other studies (4, 26–29) and is not surprising since health problems are a requirement for disability pension. Several studies have reported a significant effect of poor health on unemployment (10, 11, 14, 30), similar to the strength of the relation we found in the analysis after adjustment for demographic characteristics. Demographics attenuated the relation between poor health and unemployment from 1.56 to 1.42. Health behaviors and psychosocial work characteristics further attenuated the relation between poor health and unemployment. Poor health might particularly be a determinant of long-term unemployment, while many other factors might play a role in shorter periods of unemployment. In the current study, we did not distinguish between unemployment durations, which might explain the difference with studies using another definition. Previous research showed large differences between countries concerning the role of poor health on unemployment, which could partly be explained by national unemployment levels (11). In the current study, no major differences were found between countries with high or low labor force participation among older individuals (data not shown).

There is considerable debate concerning the role of health in retirement and specifically early retirement. In a systematic review, poor health was found to be a risk factor for early retirement (31). Based on our results, early retirement is not driven by health problems. Other factors, like financial arrangements and social factors, might be of greater importance for voluntary routes of exit (5). The discrepancy between studies on the influence of poor health on early retirement might partly be explained by different definitions of early retirement. In the current study, early retirement was defined as retirement before the official full retirement age. In other studies early retirement also includes disability pension or unemployment (12, 32). No differences were found in the relation between poor health and unemployment after stratifying Bismarckian countries (Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Netherlands, Switzerland), Scandinavian countries (Sweden, Denmark), and Southern Europe (Greece, Italy, Spain). Within countries, workers with different occupations might be handled differently. This could explain why workers in jobs with low job control are more likely to exit paid employment through disability pension.

The role of unhealthy behaviors in the working population has mostly been studied in relation to work ability, productivity loss at work, and sick leave, showing that lifestyle factors and a healthy body weight are of importance in keeping the workforce healthy and productive (16, 33–35). It has been shown that particularly smoking and obesity were determinants of disability pension (6, 15–18). In a study among employees in the construction industry, an unhealthy lifestyle predicted unemployment (10). The current study shows that the role of health behaviors differ between the pathways of leaving paid employment. A lack of physical activity was related with exit from paid employment due to disability pension and unemployment, but not due to early retirement. In the univariate analyses, obese workers also had a higher risk of exit, and after adjustment for potential confounders the estimate of obesity on exit from paid employment still indicates an increased, although non-significant, risk on disability pension and unemployment. The role of lifestyle factors on exit from work differs between countries. Overweight and obesity were more likely to be related with exit from work due to disability pension and unemployment in Bismarckian and Scandinavian countries than in Southern Europe (data not shown). Furthermore, smoking was only significantly related with exit from work in the Scandinavian region. Promoting a healthy lifestyle, particularly physical activity, might be a way to prevent workers from leaving the work force prematurely. To gain insight into the role of lifestyle on sustained labor participation, studies with a long follow-up period and repeated measurements are needed.

Another important issue is how to keep those workers with health problems at work without deteriorating their health. Favorable working conditions might play an important role in keeping workers healthy and keeping workers with health problems in paid employment. This implies that the work and working conditions need to be improved to sustain employability (36). In previous studies, a lack of job control and an imbalance between efforts and rewards were found to be associated with exit from paid employment (32, 37). This is in accordance with the current study. A lack of job control as well as low rewards were related to several pathways of exit from paid employment. The relation between these single underlying factors of respectively the job demand–control model and the effort–reward imbalance model with exit from paid employment was, except for disability pension, stronger than the combined factors. In contrast with the psychosocial work factors, no relation was found between physical job demands and exit from work after adjustment for demographic and health factors. This result might be biased due to the healthy worker effect, in which workers with physically demanding jobs had to exit their job or paid employment before reaching the age of 50 years.

There are some limitations in this study. The first is the household response of 62%, which is comparable with other European studies (38). The proportion of workers in paid employment in the study population corresponded strongly with the reported national figures on labor force participation. However, bias due to non-response cannot be ruled out in the current study. Additionally, 30% of the included respondents at baseline were lost to follow-up. In the analyses between respondents and non-respondents at follow-up, no major differences were found in health, health behaviors, and work characteristics. A second limitation is the large variation between European countries in the association between poor health and exit from paid employment (13). These variations might reflect differences between countries in the definitions of the specific pathways of exit from paid employment and institutional arrangements. Since there is a lack of power to study the determinants of labor force exit per country, countries were considered as different strata in the multivariate analyses. In Greece, none of the respondents stated they exited paid employment due to disability pension. Therefore, the Greek respondents were not included in the analysis on exiting through this specific pathway. A third limitation is that all data rely on self-reports. The assessment of self-perceived health has been found to be useful in evaluating health status in large epidemiologic studies and shown to be a strong predictor of mortality (39). A fourth limitation is the combination of employees and self-employed individuals, particularly concerning the “rewards” work factor. It was not possible to distinguish the self-employed individuals from the employees. Another limitation is potential confounding. For example, a lack of job control may be linked to other important job characteristics that are not measured in SHARE. Furthermore, in the analysis on work-related factors one must bear in mind that the self-rated psychosocial factors may reflect a large variety of particular work processes and situations that contribute differently to the observed role of these factors in exit from paid employment.

In conclusion, poor health, a lack of physical activity, and lack of job control played a role in exit from paid employment, but their relative importance differed by pathway of labor force exit. Primary preventive interventions focusing on promoting physical activity as well as increasing job control may contribute to reducing premature exit from paid employment. To maintain a productive workforce, it should be considered to integrate health promotion activities with activities aimed at occupational health and safety.