The majority of people spend a great part of their lives at work, therefore it is very important to address determinants of workplace-related mental health and develop effective strategies to preserve it. One of the major risk factors leading to poor mental health and well-being is work-related stress, affecting more than 40 million individuals across the European Union (1). Long-term exposure to work-related stress is associated with an increased risk of depression and may contribute to a range of other debilitating diseases, work injuries, and illnesses (2). Additionally, work-related stress and associated mental health problems lead to a number of major socioeconomic consequences such as absenteeism, increased turnover, loss of productivity, and high disability pension costs (3). Evidence shows that nurturing employee mental health and well-being is cost-effective for organizations and leads to higher job satisfaction, improves productivity, and contributes to lower absenteeism, resulting in increased profits for the corporation (4, 5). Thus, it is essential to develop, implement, and evaluate mental health promotion and disease prevention strategies in the workplace.

In order to implement appropriate interventions, it is necessary first to identify occupational hazards and assess both physical and psychosocial risks. This can be achieved by adopting the “systematic hierarchy of control” approach, which provides a structure for employers to select the most effective control measures (interventions) with the aim of removing or reducing the identified risk of certain hazards (6). This approach includes the following steps: (i) identifying the hazards – finding them and understanding the potential harm they can cause; (ii) assessing the risks – understanding their nature, the impact and likelihood of their occurrence; (iii) controlling hazards and risks – determining the control (ie, intervention) to eliminate or reduce the risk and selecting the best way to implement it; and (iv) checking the control – reviewing the implemented intervention(s) to ensure they are effective.

This approach does not need to include comprehensive and complex interventions, and the choice of interventions will depend on the complexity of hazards, the nature of the organization, and the way business is conducted. Different ways of controlling the risks can be ranked from the highest level of protection and reliability to the lowest. The most effective protection measure is to eliminate hazards or the associated risks, followed by efforts to reduce the remaining risks. The remaining measure involves influencing individual behavior and changing how they interact to reduce the risks (6). Since recent literature recognizes brief interventions as simple and time-efficient strategies that focus on changing behavior (7), they could be an appropriate solution for reducing the risk by influencing employee behavior.

Taking into account the fast-paced demands of modern life, it would be valuable to develop and implement appropriate and effective promotion and prevention strategies in organizational settings that do not interfere much with everyday tasks. Although there are no quick fixes in enhancing employee mental health and reducing their stress level, brief interventions could be part of the solution as a strategy for stress relief, implemented on their own or as a part of a more comprehensive organizational strategy. Additionally, their short duration and simplicity are potentially appealing characteristics for the employer, that could have a positive influence in overcoming common structural challenges and barriers of implementing mental health interventions in the workplace, such as stigma related to mental health and lack of commitment and interest on the part of employer (8).

Brief interventions are usually defined as being limited in time and focused on changing behavior (9). They emerged from addiction treatment research (10) and cover a broad range of strategies used to support people to create change over a short timeframe (11). Brief interventions can vary in session duration and frequency, usually consisting of one or multiple sessions lasting 5–60 minutes (11, 12, 13). They are often referred to as a heterogeneous entity (14) that can be delivered in various forms, such as psychoeducation, skills training, goal-setting, lifestyle changes, exercise, guided self-help, among others (11). There is substantial evidence that alcohol and tobacco-related brief interventions are effective in organizational settings (15, 16, 17). Moreover, previous studies have reported that brief interventions are practical and possibly sustainable, potentially producing beneficial results (18) at a low cost to the organization (19).

Although it would be essential for organizations interested in improving mental health and well-being of their employees to have an overview of corresponding effective brief interventions for their specific setting, no synthesis of the evidence is available so far. Previous reviews on mental health and well-being interventions conducted in organizations have mainly focused on prevention and promotion strategies (regardless of the length) (20, 21, 22), interventions for people with common mental health problems (2, 23), crisis interventions (24), and prevention of work disability (25).

The present systematic review focuses on brief interventions and includes both mental health and well-being prevention and promotion strategies. The main goal was to provide an overview of the effectiveness of brief workplace interventions carried out in organizational settings that addressed employee mental health and well-being. A relevant issue is whether brief interventions are as effective as corresponding interventions of usual length. Therefore, the additional goal is to compare the effectiveness between brief and corresponding common (ie, longer) interventions. This review will provide information about the current state of the art of brief mental health and well-being interventions in organizational settings and inform both policy and practice about the short- and long-term effects of these strategies on mental health and well-being outcomes.

Methods

A systematic review was carried out and reported following PRISMA guidelines (26).

Search strategy

The literature search was conducted in March 2016 on Medline and PsychINFO databases. The search strategy was built upon common strategies identified from relevant published articles (2, 20, 21) and was based on a combination of search terms related to workplace, mental health and well-being, interventions, and study design, both as freetext/keywords and MeSH terms. The search was not restricted to brief interventions since we aimed to include studies evaluating interventions of usual length (ie, longer, “common” duration) that matched the included brief interventions. The complete search string is presented in Appendix 1 (www.sjweh.fi/index.php?page=data-repository). The search included studies in English and German, published between 2000–2016. To identify further studies missed by the electronic search, the reference list of included articles was manually searched along with “grey literature” databases (SIGLE, NITS, reports of the Mental Health Commission of Canada/Australia/UK, MH AID New Zealand and Australia, SpringerLink database, and Google Scholar).

Selection criteria

Randomized-controlled trials (RCT) and quasi-experimental studies evaluating workplace interventions assessing mental health and well-being outcomes, such as perceived stress, resilience, job satisfaction, depressive and anxiety symptoms, positive and negative affect, and other related measures were eligible for inclusion. Primary and secondary interventions, targeting both individual and organizational levels, as well as individual and group interventions delivered face-to-face or through information technology (computer-based, smartphone applications) fit the inclusion criteria. Studies carried out among workers were considered and interventions conducted among the unemployed population or persons with diagnosed mental health conditions were excluded. Studies were included if they evaluated a brief intervention – consisting of up to five sessions with each session lasting up to an hour (12). Studies evaluating interventions of usual length – referred to as “common interventions” – were included post-hoc if they evaluated longer counterparts of included brief interventions and matched brief interventions by intervention type and assessed outcomes.

Eligibility assessment

Four researchers screened the retrieved abstracts of all studies fitting the criteria, regardless of the intervention’s duration, for relevance. In order to improve the quality and reliability of this process, an independent reviewer double checked 20% of abstracts. The fulltexts of relevant studies were retrieved and checked in two consecutive phases: (i) inclusion of studies evaluating brief interventions and (ii) inclusion of studies evaluating matched common (ie, longer) interventions. The second phase was carried out after data extraction of studies evaluating brief interventions. A second reviewer double checked all included studies regarding their eligibility and disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Data extraction and data synthesis

Extracted information about study characteristics included: aim of the study, design and study population, intervention, outcomes and assessment instruments, and findings. Additionally, data on the rationale of implementing the intervention in a particular setting were extracted. Extracted information about interventions included: name, number of sessions, duration and frequency, intervention level (individual or organizational), delivery mode (face-to-face, computer-based, online), and content. Where possible, effect sizes (Cohen’s d) of brief and common interventions were calculated and reported. Given the heterogeneity of included studies, an overall quantitative meta-analysis was not feasible. Data was synthesized by categorizing studies according to the type of intervention.

Methodological assessment

Two reviewers assessed the methodological quality of the studies using adapted checklists for RCT and quasi-experiments recommended by NICE guidelines (27). Since NICE guidelines do not provide clear cut-off criteria for methodological quality, we adapted it to the Groeneveld et al approach (28) and assessed each study as having high or low risk of bias, depending on how many relevant methodological quality criteria were fulfilled (table 1). When fulfilled and described properly, a criterion was rated as positive (+), otherwise criteria were rated as negative (-). Studies that rated positive on >50% of criteria (ie, ≥5) were considered to have low risk of bias. After independent assessment, existing disagreements between reviewers were resolved by consensus.

Table 1

List of criteria used for assessing the methodological quality of studies, adapted from checklists for randomized controlled trials and quasi-experiments recommended by NICE guidelines.

Strength of evidence

In order to draw conclusions about the effectiveness of identified intervention types, we followed the best-evidence synthesis approach adapted from Groeneveld et al (28). Four levels of evidence were distinguished depending on the methodological quality of studies and consistency of results: (i) level 1 (strong evidence) multiple RCT with low risk of bias with consistent outcomes; (ii) level 2 (moderate evidence) 1 RCT with low risk of bias and ≥1 RCT with high risk of bias, all with consistent outcomes; (iii) Level 3 (limited evidence) 1 RCT with low risk of bias or >1 RCT with high risk of bias, all with consistent outcomes; and (iv) Level 4 (no evidence) 1 RCT with high risk of bias, quasi-experimental designs or contradictory outcomes of the studies.

Consistency of results for a certain outcome measure would be reached when ≥75% of relevant studies reported significant improvement in the intervention group and no difference in the control group. In case of ≥2 high quality RCT, the conclusion was based on these RCT only. Otherwise, results of low quality RCT were taken into account.

Results

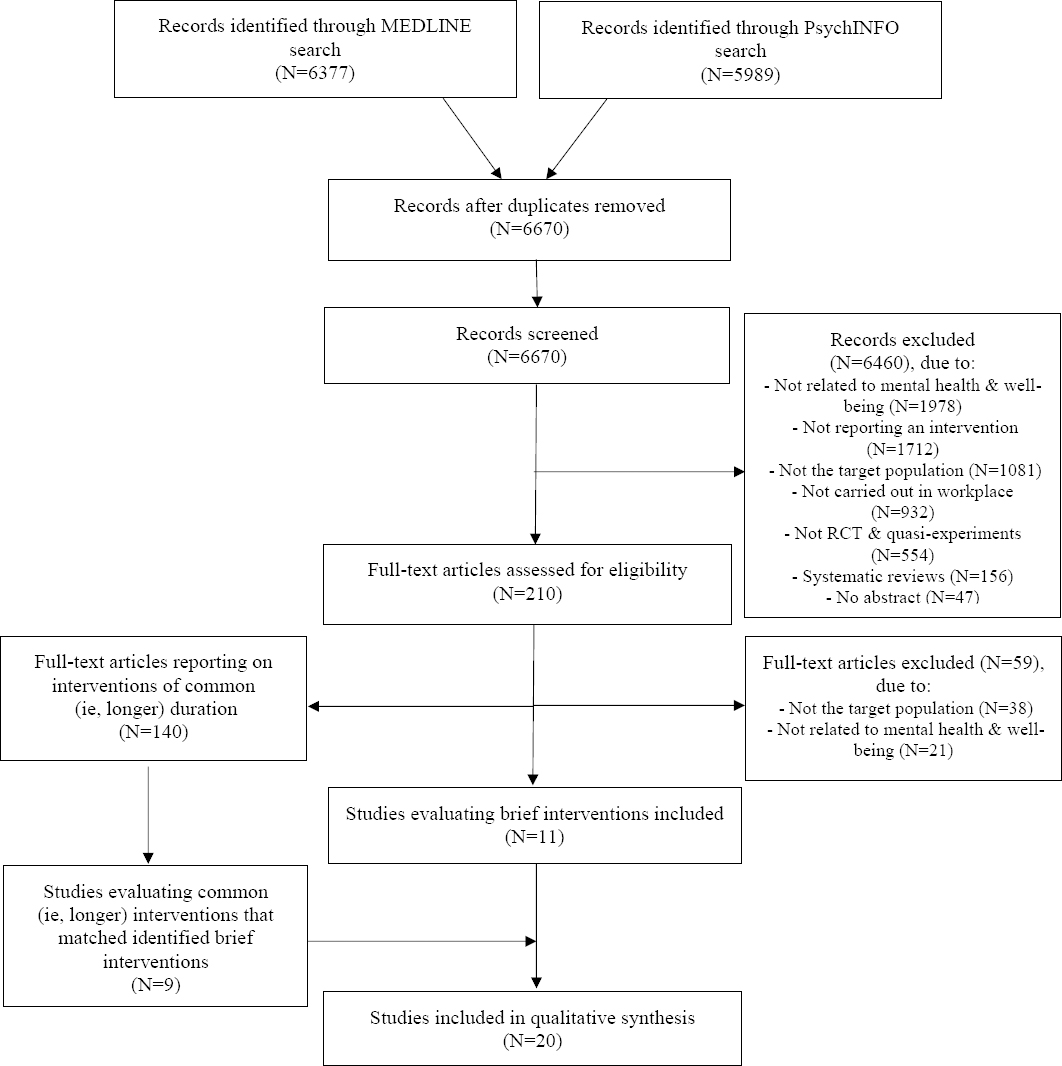

This systematic review comprised 11 studies evaluating brief workplace mental health and well-being interventions and 9 studies evaluating matched common (ie, longer) interventions. However, it is important to note that 10 studies evaluating brief interventions and 7 evaluating matching common ones had high risk of bias. The PRISMA flow diagram is presented in figure 1. A detailed description of included studies and their findings is presented in Appendix 2 (www.sjweh.fi/index.php?page=data-repository).

Summary of studies evaluating brief interventions

The sample size of the included studies ranged from 30–278 participants. All studies evaluated individual-level interventions carried out among a healthy, working population and none addressed working conditions or job stressors. Five studies included high-stress professions, such as police, healthcare staff or education professionals (29, 30, 31, 32, 33), four were carried out among office workers (34, 35, 36, 37) and two included manufacturing workers (38, 39). Studies were carried out mostly in high and middle-income countries.

Seven studies were RCT whereas the remaining had quasi-experimental designs (N=4). Four studies used pre-post-test measurements (30, 31, 32, 35) and six had follow-up ranging mainly from one week to one month (29, 33, 34, 36, 38, 39). One study implemented a 3-month follow-up (37). One study included two intervention groups (33) and the remaining studies included non-active (29, 34, 37), waiting-list (31, 39) or active (31, 32, 36, 39) control groups. One study did not involve a control group (35). Reported attrition rates ranged between 6.1–88%. Most brief interventions were delivered in weekly intervals (29, 30, 31, 33, 35, 38, 39), one was conducted daily (36), one on alternate days (32) and one every four weeks (34). One intervention was a single session (37). With regard to session duration, six interventions lasted ≤30 minutes (29, 30, 33, 35, 36, 37) and five between 30–60 minutes (31, 32, 34, 38, 39). Seven interventions involved face-to-face training (29, 31, 32, 33, 34, 37, 39), one was delivered online (35) and one was self-administered (36). Two interventions used mixed methods: face-to-face and computer-based (38), and participants receiving a CD of guided exercise after face-to-face training (30).

Types of brief interventions also varied substantially. Most studies reported on relaxation techniques (31, 33, 39) and stress management interventions (34, 35, 38), followed by positive psychology interventions (36, 37), mindfulness meditation (30), massage (29), and multi-dimensional intervention (32) which included relaxation, self-management and mood-management techniques. The assessed outcomes were mainly stress (N=5), anxiety symptoms (N=4), burnout symptoms (N=2), and well-being (N=2) (Appendix 2). Three studies included physiological outcomes, such as heart rate (31, 39), blood pressure, and cortisol level (29). No study applied clinical instruments in outcome assessment.

Summary of studies evaluating matched common (ie, longer) interventions

Based on the matching criteria, studies evaluating the following intervention types were included: meditation (40, 41, 42, 43), stress management (44, 45, 46), and positive psychology (47, 48). Their sample size varied between 40–296 participants. Four studies were carried out among office workers (40, 46, 47, 48), three included high stress professions (41, 42, 43), and two included manufacturing workers (44, 45). Similar to studies evaluating brief interventions, these studies were conducted predominantly in high and middle-income countries. Six studies were RCT (40, 41, 42, 45, 46, 48) and the remaining had quasi-experimental designs (43, 44, 47). One study included two intervention groups (40). Unlike the brief interventions, six studies had longer follow-ups of between 1–6 months (40, 41, 43, 45, 47, 48), and three studies used pre/post-test assessments (42, 44, 46). Common interventions were mainly delivered face-to-face (40, 41, 42, 44, 43, 46, 48), and two were computer-based (45, 47).

Strength of evidence

An important result of this systematic review is the high risk of bias found in 17 of the 20 included studies (table 2). Several studies were rated negatively on particular criterion due to lack of or unclear description of methodology, such as randomization and allocation procedure. Additionally, only five studies applied intention-to-treat analysis. Brief stress management (34, 35, 37), relaxation (31, 33, 39), massage (29), and one intervention with a multidimensional approach (32) were evaluated solely in studies with high risk of bias and no matched common interventions have been identified (Appendix 2). Therefore, the evidence on the effectiveness of brief interventions is considerably limited.

Table 2

Methodological quality checklist. When fulfilled and described properly, a criterion was scored as positive (+) or negative (-). Studies that rated positive for >50% of criteria (ie, ≥5) were considered to have low risk of bias; otherwise they were assessed as having high risk of bias.

Limited evidence, based on a single RCT (37), was found for brief positive psychology interventions. This RCT applied a blinding procedure, had comparable groups, analyzed if systematic differences in dropout rates were present, and had a low attrition rate and 3-months follow-up. The main aim of the study was to increase employee psychological capital, one of the core concepts of positive organizational behavior, defined as a “state-like psychological resource that comprises four components: optimism, hope, efficacy, and resilience” (37). The study consisted of a structured reading material-based brief intervention delivered in a single session. Results showed increased hope, optimism, efficacy, resilience, and job performance, but only the effect on hope remained in the 3-month follow-up. Effect sizes were small on hope and medium on overall psychological capital, resilience, and optimism. When reporting on the evidence of positive psychology, it is important to note that there is no standard definition of positive psychology interventions. The working definition applied in the present review was: “Positive psychology intervention may be understood as any intentional activity or method (training, coaching, etc.) based on (a) the cultivation of valued subjective experiences, (b) the building of positive individual traits, or (c) the building of civic virtue and positive institutions.” (49)

A relevant question in this systematic review was whether brief interventions are as effective as their common (ie, longer) versions. However, the evidence on the effectiveness of the matched common versions is limited as well. Two RCT evaluating common positive interventions were identified (47, 48), but only one had low risk of bias. This RCT evaluated the “Working for Wellness Program” (48) and showed long-term effectiveness by increasing participants’ subjective, psychological, and work-related well-being throughout a 6-month period. The study had small effects on positive and negative affect and a very large effect on affective well-being (Appendix 3, www.sjweh.fi/index.php?page=data-repository). Although both brief and common positive psychology interventions were effective, their effect sizes are hardly comparable due to the use of different outcome measures. Although we found no evidence that brief meditation interventions are effective, limited evidence based on one RCT was found on the effectiveness of common mindfulness interventions. This RCT with low risk of bias (40), carried out among media employees, showed significant improvements in general mental health and depressive symptoms but no change in job satisfaction and motivation.

Discussion

The current systematic review 11 studies evaluating brief workplace mental health and well-being interventions and 9 studies evaluating corresponding common (ie, longer) interventions. Based on these studies, there is no evidence on the effectiveness of brief stress management techniques, relaxation, mindfulness meditation, massage, or multidimensional interventions on employee mental health and well-being. We found limited evidence on the effectiveness of brief positive psychology interventions. A relevant question in this systematic review was whether brief interventions are as effective as their common (ie, longer) versions but the evidence on the effectiveness of matched common interventions is limited as well. Two RCT demonstrated the effectiveness of matched common positive psychology and mindfulness interventions. Although there is some evidence that both brief and common positive psychology interventions are effective, due to very different outcome measures, their effect sizes were largely incomparable.

An important finding of this systematic review is the high risk of bias in the vast majority of studies included. Studies were mainly assessed as having high risk of selection, performance, attrition, and detection bias, not only because of poor methodology but often due to insufficient and unclear description of methods, such as randomization, allocation, and blinding procedures. By not reporting information relevant for methodological quality assessment, studies were rated negative on particular criterion, which led to high risk of bias and hampered drawing conclusions regarding the effects of interventions on employee mental health and well-being. Therefore, there is the need for further, high-quality research with well-reported methodology to avoid potential bias and provide transparent evidence on the effectiveness of these interventions.

Based on two RCT, our review provides limited evidence on the effectiveness of brief and matched common positive psychology interventions in organizational settings. A previous systematic review and a meta-analysis, both focusing on positive psychology interventions regardless of their length, evaluated their effects on the individual’s well-being (49, 50). However, the narrative systematic review published in 2012 focused on the added value of the positive interventions in an organizational context “in the wide sense” (49) and neither appraised nor reported on the methodological quality of the 15 included studies. The meta-analysis (50) published in 2013, included 39 studies that evaluated the effectiveness of positive psychology interventions on well-being and depressive outcomes of the general public or people with specific psychosocial problems. The authors applied the Cochrane criteria in methodological appraisal of included studies. Similarly to our findings, the methodological quality of studies was rather poor, limiting the generalizability of results and leading authors to call for additional high-quality studies (50). Since positive psychology interventions are designed to build positive qualities and not treat decrements in mental functions, they are suitable for implementation in organizational settings – individually, embedded in wider programs and/or combined with other approaches. By focusing on positive aspects of an individual’s mental health, they may help reduce stigma related to mental health and could serve as a useful tool to enhance individual well-being and potentially improve individual and organizational performance (49). We further reinforce, therefore, the call of the aforementioned meta-analysis for future methodologically sound research that follows available reporting standards.

The overall number of studies evaluating brief interventions identified in our review covering scientific articles published between 2000–2016 was rather small. There might be several reasons for this scarcity. Companies are often under legal obligation to address working conditions, physical health, and safety but not specifically mental health and well-being. This could be one reason why research is aimed more towards physical health and risky behavior and less towards mental health. Additionally, employers might be concerned that addressing workers’ mental health could disclose potential mental health-related issues, such as high levels of stress, and lead to a negative impact on the company’s image. Another reason might be publication bias, understood as the increased likelihood of publishing studies reporting positive effects. However, in the present review, 50% of all included studies reported non-significant results and one study even reported on adverse effects of a common length intervention (44). Therefore, although the risk of publication bias is possible, it seems not to be a major issue in this area. Finally, one could argue that the few studies could reflect a new and perhaps growing area of research. Nevertheless, only 3 of the 11 included articles evaluating brief interventions have been published in the past five years, which speaks against this argument.

A striking finding of our review is that all identified studies evaluated individual-level interventions. According to the “systematic hierarchy of control” model, a stepped approach is required in protecting employee health and safety. The model considers elimination of risks and hazards as the most effective occupational health and safety measure, followed by efforts to reduce remaining risks and ultimately influencing individual behavior (6). Although elimination or management of hazards and risk is considered the most effective protection measure, employers tend to be more receptive to individual-level programs. A potential reason could be that organizational-level interventions, aiming to reduce psychosocial risks and hazards, are often more challenging in their implementation than individual interventions. It seems worthwhile to invest resources to further develop and evaluate individual-level brief interventions as these strategies could open the door for more comprehensive programs targeting psychosocial risks in the workplace. However, policy-makers should establish appropriate legislation to ensure that employers indeed invest more efforts in the implementation and evaluation of organizational-level interventions.

Although mental health problems at work are rising at a concerning speed, effective and feasible interventions targeting mental health and well-being are scarce. A recent OECD report (51) shows that up to 40% of workers experience high levels of job strain leading to long and frequent sickness absence. Moreover, mental health problems are linked to poor performance and high productivity losses (51). Brief interventions meet the challenge of the fast-paced modern life and are promising in organizational settings since they do not interfere much with everyday work tasks. However, evidence on their effectiveness remains inconclusive. The evidence, albeit limited, that positive psychology brief interventions are effective combined with the increasing extent of mental health problems at work point out that more attention should be given to the development and implementation of appropriate interventions as well as sound evaluation strategies that can indeed inform policy-makers about their effectiveness.

Limitations

The literature search was conducted using two databases and limited to publications in English and German. However, in order to complement the search, a very broad timeframe was considered and reference lists of included papers and additional databases were checked. Due to the high number of retrieved abstracts in this review covering a time-frame of 15 years, a second reviewer double-checked only 20% of abstracts. However, the agreement among reviewers was very high and indicates a high reliability of the abstract check process.

Implications for practice and future research

The present review provides limited evidence on the effectiveness of positive psychology interventions in organizational settings and no evidence for other types of brief interventions. We recommend further high quality research in this area for conclusive evidence on their effectiveness. Furthermore, although positive psychology is relatively new and an alternative approach in the field of workplace mental health, we recommend that employers remain open towards the implementation of such interventions.

Methodologically rigorous study designs, with greater sample size, control groups, longer follow-ups, standardized outcome measures and clear reporting of methods are needed to ensure comparison of the studies and stronger conclusions on their effectiveness. Researchers are encouraged to follow available guidelines, such as the CONSORT statement (51) for RCT, for complete and transparent reporting of their studies that would ensure a valid and comparable interpretation of obtained results. In addition, authors of future studies might pre-register their protocols containing clear descriptions of the study rationale, the need for specific interventions, and planned methodology.