Over the past three decades, the number of workers in precarious employment (eg, fixed-term, temporary contract, or contingent jobs) has increased globally (1, 2). According to statistics from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, more than half the labor force in low-income countries is currently working on limited temporary contracts or without formal contracts (3). Further, precarious employment is increasing in high-income countries, including those in Europe and North America (2, 4, 5). In South Korea, precarious workers have continuously increased from 6.1 million in 1997 to 8.7 million in 2015, comprising about half of total waged workers (6, 7).

A growing body of empirical evidence shows that precarious employment is related to worsening mental health, including psychological distress, depression, and minor psychiatric morbidity (8–20). For example, a prospective study in South Korea found that risk of depression increased among workers who changed from permanent to precarious employment compared to those who maintained permanent employment (13).

However, few studies have paid attention to the relationship between precarious employment and suicidal behaviors (ie, suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, or suicide rate) (20–25), and these studies have shown inconsistent results. A study in Germany found that temporary workers with limited-period contracts were more likely to die by suicide than permanent workers (24). On the other hand, a Japanese study showed that female temporary workers had lower prevalence of suicidal ideation than permanent workers, but noted no difference among male workers (22).

Further, most prior studies have analyzed cross-sectional datasets (20–23), which are vulnerable to potential reverse causation. We found only one cohort study of 27 446 participants in Canada reported that part-time workers and unemployed individuals were more likely to attempt suicide compared to full-time workers (25). Importantly, though, that study assessed employment status at baseline and assumed that this status did not change in the following 3.5 years. This assumption is a weakness in the study because it may have misclassified employment status that changed throughout the study.

To fill these knowledge gaps, this study examined the association between change in employment status and suicidal ideation using a nationally representative panel of data from South Korea that included baseline and follow-up employment status. We classified follow-up employment status into four categories – permanent employment, full-time precarious employment, part-time precarious employment, and unemployment – among workers who had permanent jobs at baseline.

Methods

Dataset

We employed data from the ongoing Korean Welfare Panel Study (KOWEPS), which is a nationally representative longitudinal study. The 1st wave of the dataset included 18 856 participants from 7072 households residing in South Korea who have been followed since 2006; 1800 new households were added to the panel at the 7th wave (2012) to replenish participants who were lost to follow-up during the 1st to 6th waves to maintain its representativeness. To date, data from the 1st (2006) through 10th (2015) waves of KOWEPS have been publicly released (www.koweps.re.kr), and the follow-up rate was 67.3% of original household at the 10th wave (2015) (26). This study received exempt status from the Korea University Institutional Review Board because the dataset was publicly available.

Study population and change in employment status

All study participants were workers who had permanent jobs at baseline and provided information about employment status in the following year. Employment status was classified into four categories: permanent employment, full-time precarious employment, part-time precarious employment, and unemployment. Participants were considered permanent workers if they were directly hired by an employer (not subcontracted, dispatched, or self-employed workers); did not have a fixed-term contract (not temporary workers); and had a full-time position (not part-time workers). If individuals did not meet any of these three criteria, they were defined as precarious workers and then further divided into full-time and part-time precarious workers based on working hours. Part-time precarious workers are people who work part-time hours (usually <36 hours a week), whereas full-time precarious workers are people who work regular time. Participants were considered unemployed if they were without a job at the time of survey and had been actively looking for a job during the preceding four weeks.

Change in employment status among permanent workers at baseline was categorized into four groups based on participants’ responses in the following year: permanent employment (reference group); full-time precarious employment; part-time precarious employment; and unemployment.

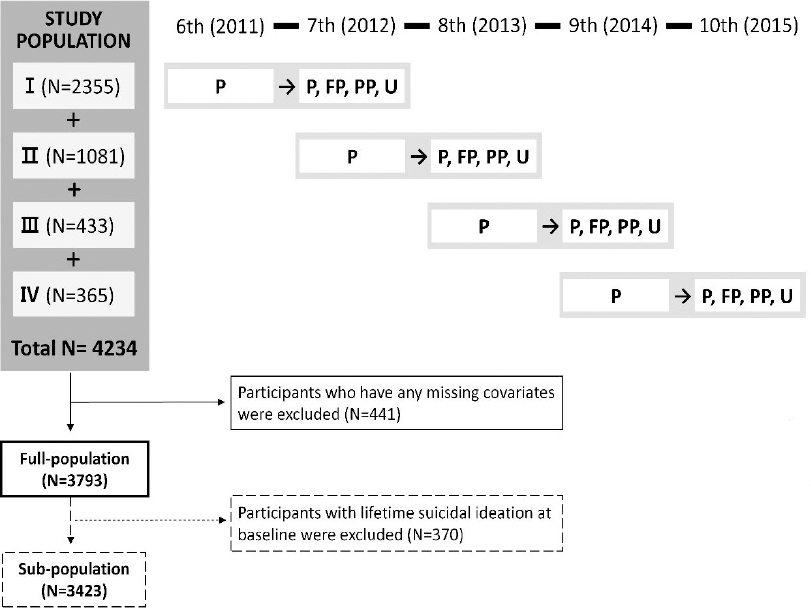

Because there were a small number of workers in certain categories who changed from permanent employment to part-time precarious employment or unemployment in the following year, we pooled four datasets (study populations I–IV) extracted from the 6th, which measured lifetime suicidal ideation at first time, to the 10th wave of the KOWEPS to maximize power of analysis (figure 1). For example, study population I included workers who had permanent jobs at baseline (6th wave, 2011) and provided information about employment status at follow-up (7th wave, 2012). We created four study populations, one for each baseline (2011, 2012, 2013, and 2014) and corresponding follow-up (2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015, respectively) year. To avoid the same person being counted more than once, we successively excluded workers who were members of the previous study population. For example, workers who were included in study population I were not considered potential members of study populations II, III, or IV (figure 1).

Figure 1

Flow-chart of study population selection from data from the Korean Welfare Panel Study (KOWEPS). Workers were divided into groups based on employment status, including permanent (P), full-time precarious (FP), and part-time precarious (PP) employment, as well as unemployment (U).

A total of 3793 participants were included in the full-population analysis, after excluding participants with missing covariate information at baseline or follow-up. When we additionally excluded individuals who had reported lifetime suicidal ideation at baseline, 3423 participants were included in the sub-population analysis.

Experience of suicidal ideation

Suicide-related variables were measured at the 6th wave of the survey for the first time. Lifetime suicidal ideation was measured with the question “Have you ever thought about dying by suicide in your life time?”, with the response options “yes” and “no”. This question was also posed to all participants who were newly added to waves 7–10. In addition, from wave 7 onwards, all participants were asked about suicidal ideation in the past year by the question “Have you ever seriously thought about dying by suicide in the past year?”, with the response options “yes” or “no”. The response to this question was the outcome measure in this study (ie, the experience of suicidal ideation at follow-up). Thus, for each of the four study populations (I, II, III, and IV) experience of suicidal ideation was measured in 7–10th wave (2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015, respectively) and was used for analyses.

Covariates

Covariates were measured at each baseline wave (6–9th) and included three kinds of variables: (i) demographic and socioeconomic variables, such as gender, age, education, marital status, equalized household income, residential area, and occupation; (ii) health-related variables, such as chronic disease and disability; and (iii) lifetime suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms at baseline.

Age was classified as <25, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, and ≥65 years old. Education was divided into junior high or less, high school graduate, college graduate, and university graduate or more. Marital status was divided into currently married, never married, and previously married including widowed and divorced. Equalized household income was calculated by dividing household income by the square root of number of household members. It was divided into four equally-sized quartiles: <1Q, 1Q–2Q, 2Q–3Q, and >3Q. Residential area was divided into metropolitan and rural areas. Health-related variables (ie, chronic disease and disability) were included as dichotomous variables (having any versus none). Occupation was categorized as eight groups: senior manager, professional/technical, clerical, service, sales, skilled, machine operator, and unskilled. Agriculture/fisheries and armed forces were not included in the analysis because there were no workers with suicidal ideation in those groups.

Lifetime suicidal ideation is an important confounder that can influence future experience of suicidal ideation and change in employment status as well. It was measured at the 6th wave (2011) and, from the 7th wave of the survey, experience of past year suicidal ideation was measured. For the newly added survey participants after 6th wave, they were asked about experience of lifetime suicidal ideation in initial wave and past year suicidal ideation in subsequent waves. We created a variable of lifetime suicidal ideation by combining the responses on lifetime suicidal ideation in initial wave (wave 6, or the later waves for newly added participants) with the responses on past year suicidal ideation in follow-up waves. Depressive symptoms were measured using the 11-question version of the Centers for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D11). The summed score of CES-D11 ranged from 0–33 and was included as continuous variables.

Statistical analysis

Multivariate logistic regressions were applied to examine associations between change in employment status and suicidal ideation. We estimated robust standard error to consider clustering among the people from same household by using a household identifier (27). Further, we checked associations in sub-populations after excluding participants who had ever seriously thought about dying by lifetime suicide at baseline. All analyses were performed using STATA/SE version 13.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Data were reported as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

Results

Table 1 shows distribution of the study population and the experience of suicidal ideation in the past year with each covariate. Overall experience of suicidal ideation in the past year was 2.1% (N=81) and tended to be higher for females, less educated individuals, previously married individuals, and individuals with lower household incomes. Service or unskilled workers, compared to other occupational groups, and individuals with chronic disease or disability, compared to individuals without chronic disease or disability, were more likely to have suicidal ideation. Suicidal ideation also appeared to be more common among individuals who had ever thought about dying by suicide in their lifetime at baseline (table 1).

Table 1

Distribution of study population and suicidal ideation by key covariates among baseline permanent workers in South Korea (N=3793). [SD=standard deviation.]

| Characteristics | Distribution | Suicidal ideation in the past year | Mean | SD | Range | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| N | % | N | % | P-value a | ||||

| Gender | <0.05 | |||||||

| Male | 2188 | 57.7 | 33 | 1.5 | ||||

| Female | 1605 | 42.3 | 48 | 3.0 | ||||

| Age (years) | <0.05 | |||||||

| <25 | 244 | 6.4 | 5 | 2.1 | ||||

| 25–34 | 981 | 25.9 | 9 | 0.9 | ||||

| 35–44 | 1202 | 31.7 | 25 | 2.1 | ||||

| 45–54 | 841 | 22.2 | 28 | 3.3 | ||||

| 55–64 | 375 | 9.9 | 11 | 2.9 | ||||

| ≥65 | 150 | 4.0 | 3 | 2.0 | ||||

| Education | <0.001 | |||||||

| Junior high or less | 629 | 16.6 | 29 | 4.6 | ||||

| High school graduate | 1471 | 38.8 | 31 | 2.1 | ||||

| College graduate | 544 | 14.3 | 5 | 0.9 | ||||

| University graduate or more | 1149 | 30.3 | 16 | 1.4 | ||||

| Marital status | <0.001 | |||||||

| Currently married | 2618 | 69.0 | 46 | 1.8 | ||||

| Never married | 861 | 22.7 | 11 | 1.3 | ||||

| Previously married | 314 | 8.3 | 24 | 7.6 | ||||

| Household income (%) | <0.001 | |||||||

| <1Q | 235 | 6.2 | 23 | 9.8 | ||||

| 1Q–2Q | 831 | 21.9 | 21 | 2.5 | ||||

| 2Q–3Q | 1236 | 32.6 | 21 | 1.7 | ||||

| >3Q | 1491 | 39.3 | 16 | 1.1 | ||||

| Residential area | 0.462 | |||||||

| Rural | 1909 | 51.5 | 45 | 2.3 | ||||

| Metropolitan | 1803 | 48.5 | 36 | 2.0 | ||||

| Chronic disease | <0.05 | |||||||

| No | 2751 | 72.5 | 49 | 1.8 | ||||

| Yes | 1042 | 27.5 | 32 | 3.1 | ||||

| Disability | <0.05 | |||||||

| No | 3559 | 95.8 | 74 | 2.0 | ||||

| Yes | 153 | 4.2 | 7 | 4.4 | ||||

| Occupation | <0.001 | |||||||

| Senior manager | 150 | 4.0 | 3 | 2.0 | ||||

| Professional/technical | 682 | 18.0 | 8 | 1.2 | ||||

| Clerical | 822 | 21.7 | 9 | 1.1 | ||||

| Service | 327 | 8.6 | 14 | 4.3 | ||||

| Sales | 266 | 7.0 | 5 | 1.9 | ||||

| Skilled | 372 | 9.8 | 3 | 0.8 | ||||

| Machine operator | 409 | 10.8 | 8 | 2.0 | ||||

| Unskilled | 765 | 20.2 | 31 | 4.1 | ||||

| Lifetime suicidal ideation | <0.001 | |||||||

| No | 3423 | 90.3 | 45 | 1.3 | ||||

| Yes | 370 | 9.8 | 36 | 9.7 | ||||

| Depressive symptoms (CES-D11) | ||||||||

| Sum of scores (≤33) | 2.64 | 3.59 | 0–25 | |||||

After adjusting for covariates that could be important confounders, including baseline depressive symptoms and lifetime suicidal ideation, our analyses showed that the odds of suicidal ideation among individuals who became part-time precarious workers were 2.4 times higher (OR 2.37, 95% CI 1.07–5.25, P=0.033) than among individuals who maintained permanent employment. Individuals who changed from permanent to full-time precarious employment also had higher odds of suicidal ideation (OR 1.41, 95% CI 0.78–2.56, P=0.256) (table 2).

Table 2

Change in employment status and its association with suicidal ideation among permanent workers at baseline in South Korea (N=3793). [OR= odds ratio; 95% CI=95% confidence interval].

| Change in employment status | Total | Suicidal ideation | Unadjusted | Model 1 a | Model 2 b | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Baseline | Follow-up | N | N | % | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI |

| Permanent | Permanent | 2899 | 45 | 1.6 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| Full-time precarious | 654 | 24 | 3.7 | 2.42 c | 1.45–4.01 | 1.67 | 0.94–2.98 | 1.41 | 0.78–2.56 | |

| Part-time precarious | 173 | 11 | 6.4 | 4.31 d | 2.21–8.40 | 2.70 c | 1.22–5.97 | 2.37 c | 1.07–5.25 | |

| Unemployed | 67 | 1 | 1.5 | 0.96 | 0.13–7.10 | 0.87 | 0.10–7.55 | 0.89 | 0.10–7.61 | |

Additionally, excluding respondents who had thought about dying by suicide in their lifetime at baseline strengthened the association of part-time precarious employment (OR 3.94, 95% CI 1.46–10.64, P=0.007) and full-time precarious employment (OR 2.33, 95% CI 1.09–4.99, P=0.029) with suicidal ideation (table 3).

Table 3

Change in employment status and its association with suicidal ideation among workers without lifetime suicidal ideation at baseline in South Korea (N=3423). [OR=odds ratio; 95% CI=95% confidence interval].

| Change in employment status | Total | Suicidal ideation | Unadjusted | Model 1 a | Model 2 b | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Baseline | Follow-up | N | N | % | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI |

| Permanent | Permanent | 2658 | 24 | 0.9 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| Full-time precarious | 561 | 14 | 2.5 | 2.81 c | 1.43–5.52 | 2.55 c | 1.19–5.46 | 2.33 c | 1.09–4.99 | |

| Part-time precarious | 145 | 6 | 4.1 | 4.74 c | 1.95–11.54 | 4.00 c | 1.51–10.62 | 3.94 c | 1.46–10.64 | |

| Unemployed | 59 | 1 | 1.7 | 1.89 | 0.25–14.30 | 2.02 | 0.23–18.11 | 1.89 | 0.21–17.48 | |

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to show an association between loss of permanent employment and suicidal behaviors. This study found that change from permanent to precarious employment was associated with suicidal ideation. Workers who changed from permanent employment to part-time precarious employment were more likely to experience suicidal ideation compared to those who maintained permanent employment, even after adjusting for potential confounders including depressive symptoms and lifetime suicidal ideation at baseline. When we restricted analysis to workers without lifetime suicidal ideation at baseline, change to either full-time or part-time precarious employment was still a risk factor for suicidal ideation even with higher odds ratio than in the main analyses (table 3).

These results are consistent with previous studies reporting that change to precarious employment may aggravate mental health outcomes. In a longitudinal cohort study conducted in Korea, Kim et al (11) found that female workers without disability or chronic disease at baseline and without depressive symptoms in the two previous years who changed from permanent to precarious employment had higher odds of developing depressive symptoms than those who maintained permanent employment. In addition, Yoo et al (13) reported that both male and female workers who became precarious employees following permanent employment were more likely to experience depression if they were the head of household.

Higher risk of suicidal ideation among individuals who became precarious workers could be explained by job insecurity or poor working conditions compared to those who maintained permanent employment. For example, precarious workers tend to work for relatively lower wages and with little protection under social security systems, such as social insurance coverage and fringe benefits (28–31). According to the Korean statistic, precarious workers are more likely to have lower incomes and poor working conditions (7). For example, precarious workers in Korea are paid only half the wages of permanent workers. Further, about 62% of precarious workers have no unemployment insurance and 81% are not eligible for overtime pay for extra hours worked, while 85% of permanent workers take out unemployment insurance and 70% are paid extra for overtime. These poor working conditions among precarious workers in Korea could negatively affect workers’ mental health, including suicidal ideation.

When we excluded participants with lifetime suicidal ideation, instead of adjusting for this variable, the OR became stronger. This might have been due to the lower number of cases per exposure group. Further studies are necessary to explain the change in those association.

Strengths and limitations

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, there was lack of statistical power to examine the association between unemployment and suicidal behaviors, although previous studies have demonstrated that unemployment is associated with higher suicidal behaviors (32–35). This result may be influenced by our small sample size of unemployed participants. In addition, although this study analyzed the longitudinal dataset, we cannot completely rule out the possibility that the suicidal ideation has occurred and afterwards the employment status has changed during the one year between baseline and following year, because there could be partial-overlap in reference period of exposure and outcome. One alternative to control this issue is to assess employment status in three waves (baseline, the following year, and the year after that) and examine its association with suicidal ideation. However, it was not feasible because an exposure variable should have 16 categories (4×4 categories) considering the change of employment status between the following year and the year after that. So, we would not have had enough number of cases in each category to examine the association. Finally, we assessed only suicidal ideation rather than ideation frequency, severity, or other suicidal behaviors such as plan or attempt of suicide. Suicidal ideation, however, can function as one of the most important predictors of suicide (36–40), so these results have practical implications for prevention or policy-making for the enormous public health problem of suicide (41, 42).

Despite these limitations, we can also note several strengths of this study. First, this is the first study to examine the association between change of employment status and suicidal ideation. Compared to previous studies with cross-sectional designs, our study is less vulnerable to potential reverse causation. Second, this study more thoroughly classified precarious employment, which reflects the current social context of the Korean labor market. Compared with previous studies that defined precarious employment using just one criterion, such as working hours (full- versus part-time) (25) or contract duration (permanent versus temporary) (22, 24), our study defined precarious employment based on three criteria: contract type, contract duration, and working hours. Additionally, we divided precarious employment into full- and part-time in effort to better reflect the disparity of working conditions between the two groups. Third, we investigated an association of suicidal ideation with employment change after adjusting for lifetime suicidal ideation at baseline as well as other potential confounders including depressive symptoms and health-related variables at baseline. Finally, we additionally examined an association of change in employment status with suicidal ideation even after excluding participants with lifetime suicidal ideation at baseline, further strengthening the association.

Concluding remarks

This study found that negative changes in employment status – from permanent to precarious employment – increase the risk of suicidal ideation. These effects were clearly identified when we restricted analysis to workers without lifetime suicidal ideation at baseline. It shows that legal or governmental protection is necessary for precarious employees who lose their permanent employment status, and further studies are necessary to investigate which kind of protection would be in urgent need for these employees.