Preventing and managing work-related musculoskeletal pain remains a challenge throughout Europe and the United States (1). Across different occupations, musculoskeletal pain is one of the principal reasons for work disability and sickness absence (2–8). Furthermore, the Global Burden of Disease Study shows that pain of the low back and neck is the leading global cause of disability (9). The economic burden of all forms of musculoskeletal conditions at the societal level is estimated to constitute 2.9% of the GDP (10). Several risk factors exist in the working environment for musculoskeletal pain and its associated consequences, eg, heavy lifting, work with bent or twisted back, repetitive and forceful work, and full-body vibration (11–14). However, individual psychological factors also play an important role (15). Importantly, negative beliefs and thoughts about pain and movement increase the risk of sickness absence, not returning to work, and sustaining chronic pain (16–18).

Short-term controlled workplace interventions focusing on psychological factors such as beliefs and thoughts about musculoskeletal pain have shown promising results. A randomized trial using psychosocial education found improvements of back beliefs among soldiers completing military training (19). Another randomized trial using a combination of physical training, cognitive training and mindfulness found improvements of work-related fear avoidance beliefs among laboratory technicians (20). A prospective study in a factory setting showed that distribution of an educational psychosocial pamphlet improved beliefs about pain control and consequences of low-back pain (21). A recent randomized controlled trial (RCT) among public-sector employees found reduced sickness absence due to low-back pain – in spite of unchanged low-back pain intensity – from group-based reassuring information and a non-threatening explanation for low-back pain to alter beliefs about back pain and activity (22). Hence, beliefs related to musculoskeletal pain, movement and work are modifiable and can lead to altered sickness behavior (22). However, the translation from research to practice – especially when going from a workplace study to the society level – can be challenging. Thus, several obstacles such as lack of reach, uptake, and sustainability in the population are seen across several scientific disciplines (23–25).

National campaigns are a method to reach a large proportion of the population. During the late 90s in the state of Victoria in Australia, Buchbinder and co-workers evaluated a media campaign concerning beliefs about back pain in the population and found both short- and long-term positive effects (26, 27). In Scotland, Waddel and co-workers evaluated the “Working Back Scotland” multimedia campaign and also found both short- and long-term effects of the campaign on back beliefs but not on sickness absence (28). In Norway, Werner and co-workers evaluated the “Active Back” media campaign targeted mainly towards the general public and health professionals, and found positive effects on back beliefs but not sickness behavior (29). Finally, in the province of Alberta, Canada, Gross and co-workers evaluated the media campaign “Don’t Take it Lying Down”, drawing on experiences from the campaigns in Australia and Scotland. In contrast to the previous campaigns, the Canadian campaign did not influence back beliefs (30). Therefore, evaluation of such campaigns in different contexts and countries are needed before solid recommendations can be provided.

During the first decade of the new millennium, it was the impression that many people in Denmark still had negative beliefs about pain, movement, and work. The opportunity to perform the national Job & Body campaign in Denmark came with the collective agreement “Kvalitetsreformen 2007” to improve the quality of the public sector. The Danish Working Environment Information Centre developed the campaign in close collaboration with researchers from the National Research Centre for the Working Environment. The campaign targeted prevention of (i) risk factors for musculoskeletal pain at the workplace, (ii) consequences for workers with musculoskeletal pain, and (iii) long-term sickness absence from work. In relation to this, the campaign highlighted five main messages: (i) stay physically active even in periods of musculoskeletal pain, (ii) prevention – and not only rehabilitation of musculoskeletal pain – is useful, (iii) perform physical exercise, (iv) create a good balance between demands of the job and the capacity of the body, and (v) physical wellbeing is a shared responsibility and should be managed together at the workplace. These messages were detailed, explained, discussed and exemplified in different ways. An overview of the campaign is summarized in a 3-minute YouTube video (31). The primary sources of knowledge for the campaign were the book The Back Pain Revolution (32); Danish reviews about sickness absence, return to work and risk factors related to physically demanding work (33, 34); previous campaigns from other countries (27–30); and best available knowledge and experience from Danish researchers in the field of musculoskeletal pain and work. An important part of the change theory of the campaign was to alter beliefs and behavior in relation to musculoskeletal pain and work through new and additional understanding of prevention in Denmark and thereby complement the more traditional approach relying on biomechanical risk factors such as heavy lifting. This was inspired by a biopsychosocial understanding of pain, ie, acknowledging that pain is multifactorial in origin and consequently that a single element would be insufficient to prevent musculoskeletal pain and its consequences effectively.

Because most of the accessible information at that time was written by and for researchers, the key facts were converted to easy-to-understand data, good advice, and a number of simple messages made accessible at the campaign website jobogkrop.dk. The content also presented “best practice” examples from different Danish workplaces having good experience with initiatives and practical tools to prevent and manage musculoskeletal disorders and its consequences. In this way, the campaign aimed to stimulate daily dialogues between co-workers, leaders, and health and safety representatives at the workplace to positively change beliefs and behavior related to musculoskeletal pain and work.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the Danish Job & Body campaign on beliefs about musculoskeletal pain and work. Because different time-wise effects may occur, and several activities were initiated at different time-points, follow-ups were performed three times within the first one-and-a-half years (short-term) and after three years (long-term).

Methods

Study design and respondents

The Danish national Job & Body campaign was initiated in 2011 and ran until until 2015. The last follow-up measurement for the present study was obtained in the second half of 2014. Thus, we were able to evaluate the first three years of the campaign. We used a prospective design with representative random cross-sectional samples of public-sector employees drawn at different time points throughout the campaign. The public-sector employees were drawn from “Epinions panel of Denmark” consisting of more than 200 000 Danes (35). Data collection was performed as web surveys, where people from the panel were invited with a web link to participate in one of the ongoing Epinion surveys. When a respondent clicks the link, s/he is directed towards the survey where there are still missing respondents within each category of gender, age, region and sector to reach the target number of representative respondents for that survey. Beforehand, the respondents do not know to which survey they will be directed. This method ensures the randomness of the sample representing gender, age, region, and sector. The inclusion criteria to be invited were (i) public-sector employee, (ii) currently employed, and (iii) age 18–70 years. Invitations continued until the number of responses were 1000. Because some respondents had an ongoing questionnaire session when 1000 responses were reached, the actual number of respondents typically exceeded 1000 a bit.

The Danish national Job & Body campaign

There were four broad elements of activities: (i) networking with employers’ associations and trade union organizations, (ii), comprehensive theme sessions with a specialized communication team, (iii) campaign tour, and (iv) mass media campaign. In addition there were a number of tools and materials to facilitate behavioral changes at the workplaces.

Campaign activities

Networking

A cornerstone of the campaign was to use existing networks to obtain a wide reach of the messages and make the local workplaces the center of action. In Denmark, the ministries, regions, and municipalities are the main point of entrance to public sector workplaces. To maximize reach, strategies for dissemination of the campaign was planned together with and spread through employers’ associations and trade union organizations as an intensive networking campaign aiming to reach as many public sector workplaces in Denmark as possible through the 21 ministries, 5 regions, and 98 municipalities – comprising close to 900 000 public-sector employees. Thus, the campaign used these networks rather than trying to establish contact with each individual workplace. Contact persons for the campaign were established in 19 of the 21 ministries, all 5 regions and all 98 municipalities. Using these networks, the campaign made contact with the existing and well-established structures at the local workplaces, ie, the health and safety organizations as well as the management, and thereby also the local health and safety representatives. In this manner, the target group was made aware of the campaign through several channels, ie, at their workplace as well as through the employers’ associations and trade union organizations. To maximize the chance of workplaces using the campaign material and messages, an important principle was that the campaign should be adaptable to the needs of each workplace. For example, the workplaces could participate whenever it best suited their plans and ongoing activities.

Communication team

The Danish Working Environment Information Centre had a specialized communication team who performed more comprehensive theme sessions – typically 2–3 hours, but sometimes the entire working day – for 9000 public-sector employees across 169 workplaces during the campaign period. The workplaces could contact the campaign team and order the visit. The theme sessions of the Communication Team were dialog-based and targeted towards taking action at the workplace and included all levels of the workplace, ie, leaders, employees as well as the health and safety organization. On a separate day before the theme session, a preliminary meeting was held with the respective workplace. During the preliminary meeting, a participatory approach to the theme sessions was emphasized – both in relation to involvement in the theme session as well as to the actions to take place afterwards. The actual theme sessions concerned three main points (i) dissemination of knowledge, (ii) dissemination of good practice examples, and (iii) hands-on activities working with methods and practical tools. The sessions typically started with a presentation about the knowledge base of the selected theme and afterwards there were questions from the audience, dialog, and work in smaller groups. The communication team facilitated the process of the dialogs and group work. The purpose of this process was to maximize the relevance of the theme session for the workplace. The sessions typically concluded with physical activities (eg, elastic band exercises) combined with knowledge of health benefits of physical exercise. After the theme session, the PowerPoint presentation as well as the materials produced during the session (eg, posters and agreement forms) were delivered to the workplace to facilitate the subsequent process of working with the chosen theme.

Campaign tour

A campaign tour was also performed, consisting of visiting larger public workplaces all over Denmark. The workplaces could contact the campaign team and order the visit. While workplaces could order the campaign tour as well as a visit from the communication team, both rarely occurred at the same workplace. Two associates travelling in a campaign bus performed a total of five campaign trips over the course of the tour. In the first and second half of 2012, the campaign bus visited 52 and 66 public sector workplaces, respectively. In the first half of 2013, the campaign bus visited 27 public sector workplaces. The activities consisted of delivering campaign materials, performing workshops, and inspiring local workplace involvement and implementation of the campaign. Typically the workplace visits were followed up by local PR about the campaign.

Mass media campaign

Finally, the campaign was supplemented by a mass media campaign to stimulate an even wider reach of the messages. In 2013, the first large mass media campaign was launched during weeks 10–16 and followed up with a large media campaign during weeks 38–40. During 2014, the mass media campaign was followed up again, although not as extensively as in 2013. First, this was targeted at media and magazines from the relevant employers’ associations and trade union organizations. Later, this was expanded to also include TV spots and online advertising. As part of this, web banners were included on major Danish news sites such as politiken.dk and ads were included on Facebook. The banners and ads delivered the campaign messages and provided a link to the campaign webpage (36). The Facebook page of the campaign (Job&krop) is still active with more than 18 000 followers as of February 2017. The content of the campaign website (www.jobogkrop.dk) has been transferred to the main website of The Danish Working Environment Information Centre (www.arbejdsmiljoviden.dk) where it will continue to be available for free.

Materials and practical tools of the campaign

A total of nine materials and tools (figure 1) were developed as part of the campaign to facilitate behavioral changes at the workplaces (i) the campaign site www.jobogkrop.dk acting as the main point of information, (ii) a dialog folder for the leaders and the health and safety organizations to facilitate joint identification of challenges and solutions, (iii) five short movies with the main messages of the campaign to put prevention of musculoskeletal pain on the agenda, (iv) a pocketbook for employees with easy-to-understand information, illustrations and explanations of physical exercises, and good advice, (v) elastic resistance bands and posters with illustrations of exercises for the neck, shoulder and back, (vi) posters for the workplace in different sizes, notepads, pens and small boxes of candy – all with the main messages of the campaign, (vii) a smartphone app with weekly updates of “good advice”, videos with physical exercises, and 1-minute movies with good advices from experts in the field (researchers and occupational physicians), (viii) an easy-to-use survey with six questions for workplaces to perform a quick evaluation of physical wellbeing at the workplace in order to stimulate the dialog about possible areas of action, and (ix) a catalog with inspiration and good advice to plan, initiate and maintain actions at the workplace to enhance physical wellbeing.

Figure 1

Illustration of the materials from the campaign, (i) the campaign site www.jobogkrop.dk, (ii) dialog folder, (iii) five short movies, (iv) pocketbook, (v) elastic resistance bands and posters with exericises, (vi) posters with the main messages, (vii) smartphone app, (viii) easy-to-use survey, and (ix) catalog with inspiration.

Budget of the campaign

The expenses during the campaign were 24 million Dkr (3.2 million Euros) to external consultants, announcements, ads, and materials. In addition, the in-house usage of working time for the Danish Working Environment Information Centre amounted to 3 full person-years per year of the campaign from 2011 to 2015, ie, a total of 15 person-years.

Outcome variable

The outcome variable – beliefs about musculoskeletal pain and work – was inspired by the Back Beliefs Questionnaire (37). Because the campaign concerned musculoskeletal pain and work in general, and was not limited to back pain only, the statements were phrased to fit the contents of the campaign and only two of the eight specifically mentioned back pain or back problems. The eight statements were: (i) Pain in muscles and joints should be prevented and actively dealt with together at the workplace, (ii) When having pain in muscles and joints, it is generally important to keep physically active, (iii) When having pain in muscles and joints, one should rest until the pain is gone, (iv) When having pain in muscles and joints, one should try to live as normally as possible, (v) Almost all people are affected at regular basis by pain in muscles and joints, but it is rarely dangerous, (vi) One can almost always go to work even if having back pain, (vii) Work is the reason that one gets back problems, and (viii) If there is imbalance between the physical demands of the work and our physical capacity, the risk of getting pain in muscles and joints increases. Respondents replied to the statements on a 5-point Likert scale of “completely agree”, “agree”, “neither agree nor disagree”, “disagree”, and “completely disagree”.

Control variables

From the register of “Epinions panel of Denmark” the following control variables were included: age (continuous), gender (woman, man), region of Denmark (North, Central, Southern Denmark, Zealand, Capital), sector of employment (municipality, region, state), occupational sector (industry, construction, transport, trading, social and healthcare, teaching and research, office and administration, agriculture and food, public service, other), and job position (employee, leader, other). In addition we asked whether the respondents had a representative role in relation to health and safety at the workplace (yes/no) by asking leaders whether they were members of the health and safety organization, MED (medindflydelse og medbestemmelse, which means influence) committee or cooperation organization and employees whether they had a position as health & safety representative, MED representative, or shop steward.

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). For the main analysis, the 8 responses about beliefs were normalized and averaged on a 0–100 scale where 100 equals completely agree for questions 1, 2, 4, 5, 6 and 8, and completely disagree for questions 3 and 7. The main analysis was the change over time in beliefs, ie, from 2011 to 2014 (including all five time points), modelled using general linear models (Proc GLM) with year 2011 as reference value. The analysis was controlled for the variables mentioned above. Estimates are reported as least square means and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each time point and differences of least square means and 95% CI for differences between time points. In an additional analysis, using the same statistical procedure and control variables, we tested the difference in beliefs at follow-up in 2014 between those who knew the campaign and those who did not.

For exploratory analyses of each of the 8 questions, the scale was dichotomized to “agree” (response options completely agree and agree) or “not agree” (the remainder response options) for questions 1, 2, 4, 5, 6 and 8, and to “disagree” (response options completely disagree and disagree) and “not disagree” (the remainder response options) for questions 3 and 7. The change in the odds for agreeing or disagreeing, respectively, from before the campaign in 2011 to the end of the campaign in 2014 was modelled using binary logistic regression (Proc LOGISTIC) with year 2011 as reference. Thus, these analyses used only the baseline (2011) and follow-up data (2014), and were also controlled for the variables mentioned above. Estimates are reported as odds ratios (OR) and 95% CI for agreeing (numbers 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, and 8) or disagreeing (numbers 3 and 7) with the beliefs statements.

Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated as the change score divided by the pooled standard deviation of all test rounds (38). For reference, Cohen’s d of 0.20, 0.50 and 0.80 corresponds to small, moderate, and large effect sizes, respectively.

Results

Table 1 shows descriptive characteristics of the study population. Because of missing values for some of the information the total number is not equal for all variables. The public-sector employees were on average 46.9 (SD 11.2) years and more than two thirds were women. All five regions of Denmark were represented, with the majority (31.8%) from the Capital Region. All three parts of the public sector were represented with the majority (55.0%) from the municipality. Furthermore, all relevant occupational sectors were represented with the majority from social and healthcare (36.1%), teaching and research (19.5%), office and administration (19.1%) and public service (16.4%). Thus, the sample largely reflected public-sector employees in Denmark. The respondents at baseline in 2011 and follow-up in 2014 were largely comparable.

Table 1

Descriptive characteristics of the study population of public sector employees in Denmark. Shown for all five rounds together, baseline in 2011 and the last follow-up in 2014, respectively. [SD=standard deviation.]

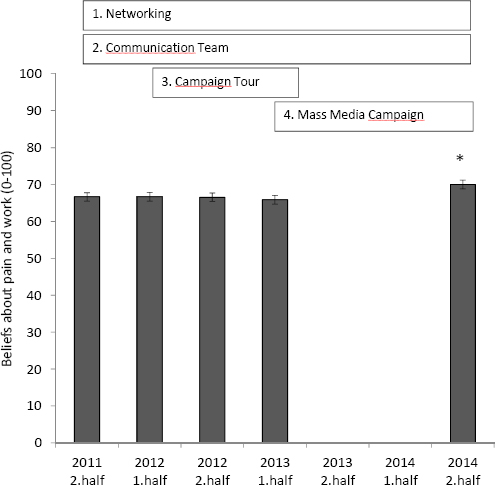

Effects of the campaign

figure 2 shows that beliefs about musculoskeletal pain and work improved 3.4 points (95% CI 2.4–4.3) – from 66.7 (95% CI 65.5–67.8) to 70.0 (95% CI 68.9–71.2) - on a scale of 0–100 from 2011 to 2014 with a significant improvement only for the last time point. The change of 3.4 points (SD 10.7) corresponds to an effect size of 0.31.

Figure 2

Beliefs about pain and work (normalized on a scale 0–100, where 100 is best) (2011–2014) among public sector employees in Denmark (N=5038). Average of the 8 questions from table 2, where complete agreement (no. 1, 2, 4, 5, 6 and 8) or complete disagreement (no. 3 and 7) is equal to 100. The analyses are controlled for age, gender, region of Denmark (North, Central, Southern Denmark, Zealand, Capital), sector of employment (municipality, region, state), occupational sector (industry, construction, transport, trading, social and healthcare, teaching and research, office and administration, agriculture and food, public service, other), job position (employee, leader, other) and having a representative role in relation to health and safety at the workplace (yes, no). Values are least square means and standard errors from the general linear model. *During the second half of 2014, beliefs about pain and work were more positive than during all the other time points (P<0.0001). The first four time-points were not significantly different from each other.

Table 2 shows that for the results of the exploratory analyses of the single questions. Out of the 8 questions, 4 showed improved odds for more positively beliefs at the last follow-up in 2014 compared with baseline in 2011 with OR ranging from 1.28 to 1.89.

Table 2

Unadjusted prevalence and adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for agreeing or disagreeing with the statements at follow-up in 2014 compared with baseline in 2011.

| Unadjusted prevalence of agreeing a or disagreeing b with the statements | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| 2011 (%) | 2014 (%) | OR c | 95% CI | |

| 1. Pain in muscles and joints should be prevented and actively dealt with together at the workplace | 53.1 | 67.8 | 1.89 | 1.56–2.29 |

| 2. When having pain in muscles and joints, it is generally important to keep physically active | 78.9 | 85.4 | 1.56 | 1.22–2.00 |

| 3. When having pain in muscles and joints, one should rest until the pain is gone | 66.1 | 70.6 | 1.28 | 1.05–1.57 |

| 4. When having pain in muscles and joints, one should try to live as normally as possible | 77.2 | 84.4 | 1.56 | 1.23–1.98 |

| 5. Almost all people are affected at regular basis by pain in muscles and joints, but it is rarely dangerous | 76.1 | 79.6 | 1.17 | 0.93–1.47 |

| 6. One can almost always go to work even if having back pain | 65.5 | 63.1 | 1.10 | 0.90–1.33 |

| 7. Work is the reason that one gets back problems | 37.6 | 33.2 | 0.88 | 0.73–1.07 |

| 8. If there is imbalance between the physical demands of the work and our physical capacity, the risk of getting pain in muscles and joints increases | 81.4 | 82.5 | 1.08 | 0.85–1.38 |

c Controlled for age, gender, region of Denmark (North, Central, Southern Denmark, Zealand, Capital), sector of employment (municipality, region, state), occupational sector (industry, construction, transport, trading, social and healthcare, teaching and research, office and administration, agriculture and food, public service, other), job position (employee, leader, other) and having a representative role in relation to health and safety at the workplace (yes, no).

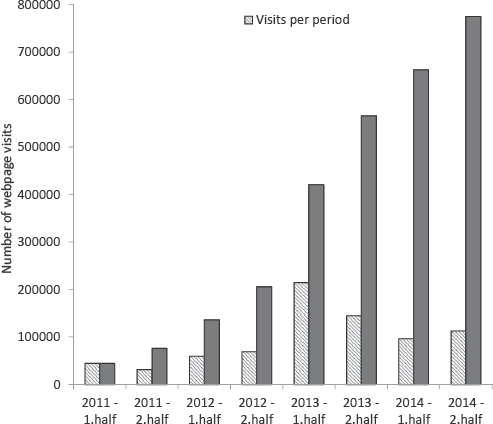

Reach of the campaign

figure 3 shows that there were some visits to the website in 2011 even before the main campaign activities were launched. Between 2011 and 2014, the highest number of visits occurred during 2013. The cumulative number of visits over time showed that at the last follow-up in 2014 nearly 800 000 visits were reached. The corresponding number of page views was approximately three times as high (not shown in figure). For the other materials in the campaign (figure 1), the movies were watched 34 000 times on YouTube, 15 000 dialogue folders were distributed, 125 000 pocketbooks were distributed, 25 000 elastic bands and 40 000 posters with exercises were distributed, 90 000 campaign posters, 40 000 pens, 60 000 notepads were distributed, the campaign app was downloaded 5000 times, the survey in digital and analogue format was ordered 248 and 1000, respectively, and 4000 samples of the catalog with inspiration were delivered.

Figure 3

Number of visits to the webpage of the campaign (www.jobogkrop.dk) during 2011 to 2014. Visits per period as well as the cumulative number of visits are shown.

Knowledge of campaign

At the last follow-up in 2014, 17.3% of the respondents replied “yes” to the question about whether they knew the Job & Body campaign. Those who knew the campaign scored 3.7 (95% CI 1.7–5.7) points higher on beliefs about musculoskeletal pain and work than those who didn’t know the campaign. Among those who knew the Job & Body campaign, 56% stated that the campaign had provided them with relevant research based knowledge about prevention and management of musculoskeletal pain, 60% stated that the campaign had provided them with methods and practical tools to prevent and manage of musculoskeletal pain, 37% stated that their workplace had initiated activities because of the campaign, and 49% stated that the campaign had led to dialogues with other colleagues about prevention and management of musculoskeletal pain. Corresponding percentages only among those having a representative role in relation to health and safety at the workplace was 24% (knowledge of campaign), 58% (provided relevant knowledge), 70% (provided methods and practical tools), 50% (initiated workplace activities), and 70% (campaign led to dialogs with colleagues).

Discussion

At the last follow-up of the Danish national Job & Body campaign, beliefs about musculoskeletal pain and work were more positive among public-sector employees in Denmark. Those who were familiar with the campaign at follow-up in 2014 scored higher on beliefs than those who didn’t know the campaign. Due to the time-wise mixture of several campaign activities, the isolated effect of each component cannot be disentangled. Whether changes in health occurred remain unknown.

The campaign was inspired by a biopsychosocial understanding of pain, ie, acknowledging that pain is multifactorial in origin and consequently that a single element would be insufficient to effectively prevent musculoskeletal pain and its consequences. For example, (i) the biological components of the campaign included biomechanical factors such as preventing unnecessary heavy occupational lifting and creating a better balance between the physical work demands and the physical capacity of the individual; (ii) the psychological components included factors such as staying active in spite of pain, relating to psychological phenomena such as “fear avoidance”, and (iii) the social components included factors such as dealing with the problems together at the workplace, involving the individual, group, organization, and management. Although the first of these – biomechanical factors – may also be viewed as an “injury model” approach, our point of view is that biomechanical factors are a natural part of a biopsychosocial approach. For example, staying physically active during periods of pain, but avoiding unnecessary heavy lifting, is not contradictory to nor in conflict with a biopsychosocial approach including biological, psychological and social components.

Based on effect size calculations, the overall effect of the Job & Body campaign on beliefs about musculoskeletal pain and work was small to moderate. In previous campaigns, effects have ranged from none to moderate (27–30). While single workplace interventions or clinical treatment of back patients often show larger effect sizes than campaigns, the present results are quite positive considering that they represent all public-sector employees of Denmark. However, whether the small to moderate change in beliefs about musculoskeletal pain and work leads to measurable changes in health or health behaviors are unknown. Buchbinder and co-workers have argued that campaigns are necessary to make changes in beliefs and attitudes in the society for highly prevalent conditions, eg, in the case of back, neck and shoulder pain (26, 27). By contrast, single efforts for preventing musculoskeletal pain and its consequences are unlikely to have the necessary reach to make a broad impact in society in terms of knowledge and beliefs. Because musculoskeletal pain is widespread across job groups, age and gender, campaigns may be the most practical tool to create changes in beliefs at the society level. However, in spite of positive results for pain beliefs in three out of four campaigns from other countries as well as from the Danish campaign, the overall impression is that such campaigns do not affect sickness absence or sickness behavior (27–30). Although not evaluated in the Danish Job & Body campaign, changes in sickness related outcomes at the national level likely require greater efforts than campaigns alone. Due to the complex nature of sickness absence behavior, the design of the present study does not allow for any type of valid evaluation of such outcomes.

Exploratory analyses of the single questions provided further information in the evaluation of the campaign. For the single questions, 4 out of 8 showed improved odds for more positive beliefs about musculoskeletal pain and work. The belief that musculoskeletal pain should be prevented and dealt with at the workplace was improved most with an OR of 1.89 (question 1) and was one of the main messages of the campaign. The questions concerning musculoskeletal pain and physical activity (questions 2, 3, and 4) were also improved. These questions were also central to the main messages of the campaign. By contrast, the questions that concerned back pain and work (numbers 6 and 7) – rather than musculoskeletal pain and physical activity in general – were not improved with the campaign. Only one third of the public-sector employees disagreed that work is the reason that one get back problems. Although prospective epidemiological studies show that work can indeed lead to back pain, eg, heavy lifting or work with bent back (12, 13), psychosocial factors at work, lifestyle, genetics etc, also influence the risk for back pain. Thus, from a scientific point of view it is difficult to argue that work is the reason for back pain, but rather that it is one of many reasons. The low prevalence of public-sector employees disagreeing with that specific question may reflect some deeply rooted beliefs about back pain and work in the population that are difficult to move at the society level. By contrast, the campaign by Buchbinder and co-workers succeeded in improving back beliefs based on the standardized Back Beliefs Questionnaire. The reason that we did not find improvements concerning the back specific questions may be that our campaign had a broader focus about musculoskeletal pain, physical activity and work, whereas the campaign by Buchbinder and co-workers had a more specific focus on the back. This suggests a certain level of specificity of the outcome in relation to campaign messages. For the last two questions, the prevalence agreeing with statements 5 and 8 were quite high at baseline (76% and 81%, respectively) and did not improve further, which may indicate a ceiling effect for these types of questions or that the campaign messages concerning these aspects did not get adequately through.

We also evaluated the campaign’s reach. At the end of 2014, the proportion of public-sector employees indicating that they knew the Job & Body campaign was 17.3%. Awareness among the target population in the previous campaigns – although evaluated using different methods and at different times points of the campaigns – have ranged from 39–86% (27–30), with the highest level in the Australian campaign. In the Danish Job & Body campaign, messages were spread in different ways and through different channels. Consequently, it is likely that the campaign messages reached a higher proportion than those indicating that they knew the specific Job & Body campaign. Thus, one may get the messages without consciously connecting this to or knowing the specific campaign. Nevertheless, that only 17.3% indicated that they knew the campaign may also reflect that we live in a society with exposure to huge amounts of information – so-called “information overload” – with concomitant difficulties in harvesting the most relevant parts. This phenomenon is for example well-known in healthcare (39). Those who indicated that they knew the Job & Body campaign reported that the information was relevant and behavioral changes had occurred at the workplace level. More than a third stated that their workplace had initiated activities because of the campaign, and about half stated that the campaign had led to discussions with other colleagues about prevention and management of musculoskeletal pain. This further supports that even without knowing the Job & Body campaign, the messages could have been spread through daily dialogs with colleagues who knew the campaign and through activities at the workplace initiated due to the campaign. The high cumulative number of visits to the website of the campaign – almost 800 000 at the end of 2014, in a country with about 5.7 million inhabitants of which about 900 000 are public-sector employees –also indicates that relatively many people were exposed to the website part of the campaign. Because the website is in Danish, it is unlikely that people from other countries have markedly influenced the number of visits. Although people may visit the website on several different occasions, the cumulative number of visits indicates that the campaign reached a high number of people.

Because different time-wise effects may occur, and several activities were initiated at different time-points, we performed both short- and long-term follow-up measurements. The change in beliefs became significant only at the end of 2014, ie, three years after commencement of the campaign. The cumulative number of website visits may be a good proxy measure for the overall reach of the campaign. The number of website visits was lowest in 2011, ie, the year when the website was finalized, which is not surprising considering that the mass media campaign had not begun. The number of visits became slightly higher in 2012 when the first wave of workplace visits had taken place. A marked boost in website visits was observed in the first half of 2013, ie, during the period with the first mass media campaign. In relation to this, beliefs about musculoskeletal pain and work only became significantly more positive at the last follow-up in 2014, which indicates that long-term campaigns targeting several channels – networking activities, workplace visits and mass media campaigns – are necessary to make changes at the national level. The results also indicate that the time from launching a campaign until the messages are spread in the society and take effect may take some years. However, due to the mixture of several campaign activities the isolated effect of each component cannot be disentangled. Timing of delivery of each component makes it difficult to know whether the observed changes were caused by the long-term efforts since 2011 or by the mass media campaign delivered during the later phase. Leavy and co-workers performed a systematic review of mass media campaigns for increasing physical activity in the population, which highlighted the importance of raising awareness of the campaign in the target group as a first step, eg, through mass media communication (40). Instead we chose to raise awareness through existing networks. In hindsight, an initial mass media campaign in 2011 in addition to the networking strategy might have provided even more positive results.

While the present campaign was ongoing, Gross and co-workers published an important paper summarizing the results and experiences from the previous campaigns (41). Through a workshop with leading experts in the field and a literature review, recommendations for future campaigns were put forward. A key message was that legislative and health policy changes should go together with public education for massive societal changes to occur. The most successful of previous campaigns, ie, the Australian, used both downstream approaches – consisting of efforts to influence individual behavior – and upstream approaches – consisting of efforts to influence behavior of governments and health policy-makers (26, 27). Gross and co-workers calls this combined down- and upstream approach “social marketing” (41). Our campaign had a strong involvement of the employers’ associations and trade union organizations in the initial phase of the campaign and in this way the campaign made contact with the existing and well-established structures at the local workplaces, ie, the health and safety organizations as well as the management, and thereby also the local health and safety representatives. Thus, the campaign was not only targeted to individual employees, but also to the entire structure and network around the employee, and thereby contained to a certain degree of both down- and upstream elements.

The changes in beliefs about musculoskeletal pain and work in response to the Job & Body campaign should be considered in the light of the costs. The networking activities involving employers’ associations and trade union organizations to reach all public sector workplaces in Denmark were comprehensive. Thus, the cost of the campaign was €3.2 million for external consultants, announcements, ads and materials, and additionally 15 person-years in time spent for employees in-house. However, rather than performing solely a mass media campaign – which would have been less costly – we expected that the networking activities would increase reach and that the workplace visits would maximize relevance for individual workplaces. Furthermore, the cost of the campaign should be seen in the light of the high cost of musculoskeletal disorders in Denmark, eg, the annual cost in Denmark for disability pensions alone is about Dkr40 billion (~ €5.3 billion) of which more than 20% of the cases are due to musculoskeletal disorders.

This study has both strengths and limitations. More than 20% of the respondents had a role in relation to health and safety at the workplace, suggesting that there may be a selection bias, ie, those working with health and safety at the workplace may have been more interested in participating. However, this was quite similar between baseline and follow-up. This was not an RCT, but an evaluation of a real-world large scale national campaign. Because a cornerstone of the campaign was to utilize existing networks that are already closely connected across Denmark, it was decided not to randomize in two groups of campaign / no campaign to different parts of Denmark. Even with a cluster randomized design, eg, randomizing different parts of Denmark to the campaign, marked contamination between groups would likely have occurred. In contrast to tightly controlled RCT designs, a number of uncontrolled variables exist in national campaigns. If simultaneous changes occurred in the general working environment, health or lifestyle in Denmark this would be able to influence the results. However, national surveillance data have shown that only minor changes – in both positive and negative direction – in the working environment, health and lifestyle of the working population have occurred during the period 2012–2014 (42). Altogether, general changes during this period are unlikely to explain the present findings of more positive beliefs about musculoskeletal pain and work among public-sector employees. Nevertheless, without a randomized design we cannot be certain about causality of associations. A strength of the study is this can be considered a real-world experiment. Although we did not have information on non-respondents, the study population at baseline and follow-up were quite comparable, and the analyses were controlled for a number of factors that may influence the belief scores. Furthermore, the results points in the same direction as three of the four previous campaigns with similar topics (26–30). Instead of a cohort study, we chose to use a prospective design with random cross-sectional samples at different time points. The strength of this design is that the respondents were not affected by having replied to same questionnaire previously. Together with the previous four campaigns from other countries, this strengthens the overall validity and generalizability of intensive and long-term national campaigns to influence beliefs about musculoskeletal pain and work in the population.

Concluding remarks

In conclusion, beliefs about musculoskeletal pain and work were more positive among public-sector employees in Denmark at the end of the Job & Body campaign. Due to the mixture of several campaign activities, the isolated effect of each component cannot be disentangled. Furthermore, timing of delivery of each component makes it difficult to know whether the observed changes were caused by the long-term efforts since 2011 or by the mass media campaign delivered during the later phase. Finally, the effect size of changes in beliefs was small to moderate, and whether this resulted in altered health remain unknown.