The potential association between shift work and breast cancer has been of longstanding interest to the global cancer research community in pursuit of more detailed and precise evidence regarding risk. Several meta-analyses synthesizing the growing body of epidemiological evidence on this topic have been published since the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC)’s 2007 evaluation of shift work involving circadian disruption as a probable carcinogen for the female breast (1). Since these meta-analyses have been published in a short time span, it is important to amass, summarize, and critically evaluate the methods and conclusions of these reports regarding night shift work as a potential breast carcinogen and to reflect on how they may be interpreted by scientists and policy-makers.

We conducted a search for and quality assessment of all meta-analyses on shift work and breast cancer risk, published in peer-reviewed journals, in order to synthesize results, compare and contrast findings. This exercise also allowed us to identify research gaps and discuss implications for potential future hazard and risk assessments of shift work involving circadian disruption.

Methods

We searched PubMed and Embase for meta-analyses and systematic literature reviews published between 2007–2017 without language restrictions. Meta-analyses had to report at least one pooled effect size (ES) for any metric of exposure to shift work involving nights and breast cancer incidence or mortality risk. The stated objectives, methods, and conclusions of each meta-analysis were summarized. Pooled ES from each meta-analysis were extracted and qualitatively compared by the following characteristics of reviewed studies: night shift work exposure metric and method of exposure assessment, occupation, study design, and adjustment for multiple covariates. Test results for heterogeneity and publication bias were extracted from each meta-analysis. Among the reviews that reported on a given metric, the results were deemed to be consistent if ≥50% of the pooled ES were statistically significant [ie, the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the pooled ES was >1.0]. Pooled ES for the ever versus never night shift work exposure metric were found in most meta-analyses and were used to reach the overall conclusions.

The AMSTAR 2 critical appraisal checklist was used to rate the methods and reporting of each meta-analysis (2) in order to identify their potential strengths and deficiencies and to explore opportunities for future research. In the checklist, the term “intervention” was replaced with “exposure to night shift work”, and the term “comparator group” with “any shift work schedule aside from night shift work”.

Results

Seven meta-analyses published between 2013–2016 collectively included 30 cohort and case–control studies spanning 1996–2016 (3–9). One meta-analysis accounted for variation in exposure assessment between studies (3); two explicitly sought to evaluate breast cancer pooled ES associated with long- versus short-term night shift work (4, 5); two included prospective studies only (6, 7); one focused on studies of breast cancer morbidity and all-cause mortality (6); and one included studies of different sources of circadian disruption (8). In most meta-analyses (3–7, 9), multiple scientific databases were searched to identify eligible epidemiological studies.

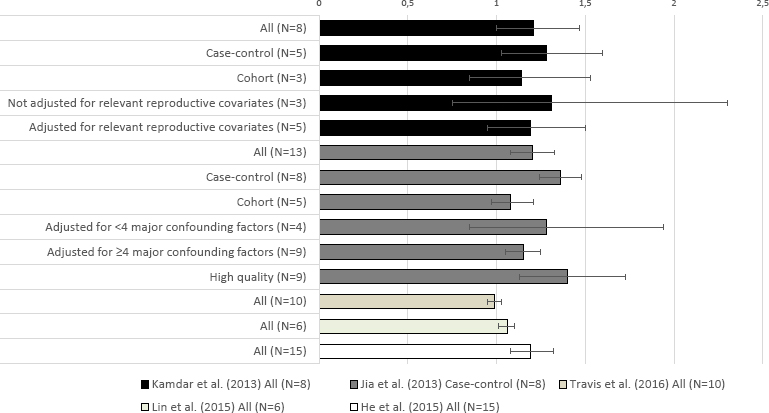

Meta-analyses largely showed positive associations between ever versus never shift work involving nights and breast cancer risk. In the five meta-analyses that reported on this metric (4, 6–9), pooled ES ranged from 0.99 (95% CI 0.95–1.03, N=10 cohort studies) (8) to 1.40 (95% CI 1.13–1.73, N=9 high quality studies] (9) (table 1). When studies were evaluated altogether or by certain study characteristics, over half of these positive associations were statistically significant (figure 1).

Table 1

Pooled effect sizes (ES) for breast cancer in association with ever versus never, duration, frequency, and cumulative night shift work exposure as reported in included meta-analyses of all studies [CI=confidence interval; NR=not reported].

| Meta-analysis first author (year of publication) | Night shift work exposure category | Pooled ES | 95% CI | Studies (N) included in pooled ES |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ever versus never night shift work exposure | ||||

| Jia et al (2013) a | Ever versus never | 1.20 | 1.08–1.33 | 13 |

| Kamdar et al (2013) b | Ever versus never | 1.21 | 1.00–1.47 | 8 |

| Travis et al (2016) c | Ever versus never | 0.99 | 0.95–1.03 | 10 |

| Lin et al (2015) c | Ever versus never | 1.06 | 1.01–1.10 | 6 |

| He et al (2015) | Ever versus never | 1.19 | 1.08–1.32 | 15 |

| Duration of night shift work exposure | ||||

| Ijaz et al (2013) a | Per 5-year increment | 1.05 | 1.01–1.10 | 12 |

| Kamdar et al (2013) b | <8 years versus never night shift work | 1.13 | 0.97–1.32 | 13 |

| ≥8 years versus never night shift work | 1.04 | 0.92–1.18 | 9 | |

| Wang et al (2013) a | Per 5-year increment | 1.03 | 1.01–1.05 | 10 |

| Jia et al (2013) a | ≥15 years versus never night shift work | 1.15 | 1.03–1.29 | 8 |

| Travis et al (2016)c | ≥20 years versus never night shift work | 1.01 | 0.93–1.10 | 8 |

| ≥30 years versus never night shift work | 1.00 | 0.87–1.14 | 4 | |

| Lin et al (2015) c | Per 5-year increment | 1.02 | 1.00–1.04 | 4 |

| <5 years night shift work versus daytime work | 1.03 | 0.97–1.09 | 4 | |

| 5-10 years night shift work | 1.03 | 1.01–1.04 | 4 | |

| 10-20 years night shift work | 1.07 | 1.01–1.14 | 4 | |

| >20 years night shift work | 1.09 | 1.01–1.17 | 4 | |

| He et al (2015) | Per 10-year increment | 1.06 | 0.98–1.15 | NR |

| Frequency of night shift work exposure | ||||

| Wang et al (2013) a | Per 3-night shifts/month increment | 1.02 | 0.97–1.09 | 3 |

| Cumulative night shift work exposure | ||||

| Ijaz et al (2013) a | rPer 300-night shifts increment | 1.04 | 1.00–1.10 | 8 |

| Wang et al (2013) a | Per 500-night shifts increment | 1.13 | 1.07–1.21 | 4 |

Figure 1

Pooled effect sizes [ES (horizontal axis)] for ever versus never shift work involving nights and breast cancer risk in meta-analyses that reported on this association. Error bars: 95% confidence intervals for pooled ES. * Statistically significant pooled ES.

Some individual epidemiological studies have found elevated risks of breast cancer among women who worked shifts involving nights for thirty years or more (10, 11). However, pooled ES for duration of night shift work exposure largely hovered around the null, and were not statistically significant, as reported in seven meta-analyses that calculated breast cancer risks for categorical or ordinal metrics of number of years of night shift work (3–9). Only one meta-analysis included a pooled ES for frequency (per three night shifts/month) (5) and two included pooled ES for cumulative lifetime night shift exposure (3, 5) and breast cancer risk; nearly all of these associations were null (table 1). Few reviews reported pooled ES for other exposure metrics. Of the reviews that did, the pooled ES were not directly comparable. Some were reported on as continuous (eg, breast cancer risk associated with every 5 years of shift work) and categorical (eg, breast cancer risk associated with >15 years of shift work) metrics. The respective intervals of these continuous and categorical metrics also differed between reviews. For these reasons, it was not possible to conclude about potential associations with breast cancer risk.

Considering exposure assessment of ever versus never night shift work, the pooled ES of breast cancer that used census or job-exposure-matrix-derived data (pooled ES=1.35, 95% CI 0.97–1.89, four studies) was higher than the pooled ES that used self-reported exposure data (pooled ES=1.14, 95% CI 0.89–1.47, three studies) and the pooled ES that used a combination of both exposure assessment approaches (pooled ES=1.00, 95% CI 0.90–1.47, one study) (4).

Few meta-analyses evaluated aggregate risks by occupation (4, 9). Among nurses, there were slight excesses of breast cancer associated with ever versus never night shift work (pooled ES=1.15, 95% CI 1.03–1.29, N=4 studies) (9) and eight or more years versus never night shift work (pooled ES=1.14, 95% CI 1.01–1.28, N=4 studies) (4). Meta-analyses of cohort (3–5, 8, 9), and more fully-adjusted studies (4, 9) generally resulted in lower pooled ES than case–control (3–5, 8, 9), or minimally-adjusted studies (4, 9).

Most meta-analyses were conducted using random effects models due to statistically significant between-study heterogeneity, reported as I2 values that were >50% in four papers (3, 4, 8, 9). Publication bias was not evident in any meta-analysis. Five meta-analyses appraised the quality of reviewed studies using different tools. The quality of these studies was generally rated as low (3–5, 8, 9). One meta-analysis included a sub-group analysis restricted to nine high-quality studies (9). Risk of bias was evaluated in two meta-analyses (3, 5) and reported as moderate overall in one paper (3).

Using the AMSTAR 2 quality assessment checklist, only Ijaz et al’s meta-analysis (3) was rated as high quality. The authors appropriately addressed several critical domains in the checklist; most importantly, they assessed and discussed the potential impact of risk of bias (using a standardized tool). The authors also cited a protocol established prior to executing the review, reported funding sources in individual epidemiological studies, and provided a list of excluded studies with reasons for exclusion. Additional deficits of the other reviews were potentially biased study selection and the study selection and data extraction by only one author.

Discussion

In this qualitative evaluation of seven meta-analyses, there was fairly consistent evidence for a positive association between ever versus never night shift work and breast cancer risk. However, confidence in the results of these meta-analyses was found to be low to moderate primarily because they did not include risk of bias assessment. There were insufficient and incomparable data on duration, frequency, and cumulative lifetime night shift work exposure and breast cancer risk. Like the authors of all papers, we acknowledge and agree that further high-quality research is needed.

Results from meta-analyses need to be interpreted with caution since the studies and relative risks that they reviewed were not directly comparable to each other and generally of low quality. As expected, epidemiological studies done in various settings and among diverse populations show substantial methodological variation. A major source of heterogeneity in meta-analyses was the varying methods used to define and assess night shift work exposure in reviewed studies. Meta-analyses of ever versus never night shift work likely yielded a range of results partly owing to this fact. Incomparable results found for other night shift work exposure metrics could also be somewhat due to differences in exposure assessment methods between studies. There is a need for several objective and standard approaches to capture relevant aspects of shift work in subsequent investigations. There was also inconsistent adjustment for known and potentially confounding variables of the association between shift work and breast cancer in the individual epidemiological studies included in meta-analyses, as well as in the methods used to ascertain covariate information. Lastly, the possibility of some residual bias cannot be ruled out. To capture the greatest number of epidemiological studies, it would be prudent for future systematic reviews to include publications in all languages, when possible; case–control and cohort designs; reports on workers in most occupations and industries; and papers that state a clear definition of “night shift work” in their evaluations of breast cancer risk.

Shift work involving circadian disruption is a priority for evaluation by the IARC Monographs program by the year 2019 (12). Whether meta-analyses published to date may help tip the scale towards a definite human carcinogen classification or not hinges on a meticulous and cautious review of their selection criteria, statistical analyses, and quality. The present review of seven meta-analyses indicates consistent associations between ever versus never night shift work and breast cancer risk, but with critical concerns regarding their quality and inadequate and incomparable information for duration, frequency, and cumulative lifetime exposure to night shift work. Important methodological advancements in both meta-analyses and individual epidemiological studies are crucial for gaining a better understanding of its potential impact on breast cancer risk. Any future evaluations of the carcinogenic potential or cancer risks of shift work need to consider results from high quality meta-analyses that exhaustively review all available studies, with better assessment of individual study quality.