People’s cognitive and physical abilities have been reported to change with age. Although there is quite some variability (1–3), several authors describe a general decline in cognitive abilities with age (1, 2, 4–10). For example, Schaie (4) documents gradual age-related declines in the cognitive domains of verbal meaning, spatial orientation, inductive reasoning, numbers and word fluency. Relatedly, Salthouse (6) finds that such cognitive declines start as early as at age 25 and become gradually more pronounced as aging progresses. Other researchers have found evidence for neurological (9) and genetic (3) foundations for these age-related cognitive declines. Importantly, knowledge and experience are found to accumulate (or crystallized intelligence) with age, contrasting with the declines in more fluid aspects of cognitive abilities (11). Concerning physical abilities, evidence for age-related declines seems convincing as well. Although inter-individual variance increases with age (12, 13), at some point in early- to mid-adulthood, physical strength (14, 15), endurance (16), psychomotor abilities (17), sensory functions (18), and general health (19) begin to gradually decline across individuals. Thus, although “a gray head is a crown of glory”, natural aging seems to have negative physical and cognitive side-effects [see (20) and (21) for comprehensive overviews].

Age-related declines in abilities are frequently thought to affect functioning at work. A common stereotype about older employees is that they perform less well than younger employees (22). Although there are some studies that find such relationships (23), others do not report any relationship between age and job performance (24) or find positive associations (25, 26). These mixed findings can be understood by considering ways in which older employees can compensate age-related declines in abilities (eg, continuous learning and increased reliance on accumulated expertise) (27) as well as the irrelevance of some abilities for functioning at work (eg, because job types and requirements may differ with age) (28). Additionally, within-age-group differences appear to be larger than between-age-group differences (22). As such, there is little justification for the stereotypical idea that older workers function less well at work. Still, the idea that older workers function less well seems to persist among both employers and older employees themselves (29, 30) and affect employment decisions (22).

Aging and sustainable employability

Combined with ongoing population aging and an increasing retirement age, the presumed association between age and functioning at work has inspired research on sustainable employability (SE). SE focuses on individuals’ ability to function at work and on the labor market throughout their working lives (31, 32). Research on SE strives to identify the conditions that enable people to work until (or beyond) their formal retirement age. This is considered important in light of the increasing retirement age because, so goes the reasoning, working lives cannot simply be extended without any facilitation (eg, in the form of age-conscious human resources practices). Unsurprisingly, much of the early research on SE has focused on older employees (see 33 for a comprehensive overview), who are considered at most immediate risk of labor market withdrawal. Another key assumption underlying this focus is that as the workforce is aging, the prevalence of chronic health problems increases which, in turn, is thought to have consequences on employees’ SE (33). The question, however, is whether this focus on older employees is actually warranted by an association between age and SE.

As time plays a crucial role in the concept of SE, a potential association between age and SE would have several important implications. That is, the currently most progressive (34) approach to SE defines the concept as a multifaceted longitudinal construct (32). Specifically, the employability component of SE can be captured as a formative construct (35) consisting of nine complementary indicators of functioning at work and on the labor market (ie, perceived health status, need for recovery, fatigue, work ability, job satisfaction, motivation to work, job performance, skill gap and perceived employability). The sustainability aspect can then be captured by considering this formative construct at multiple points in time. Stability and growth in the construct indicate sustainability, whereas declines indicate a lack thereof (32). By extension, if development in these nine functioning indicators is entirely attributable to natural aging, very little can be done to promote SE. Additionally, if age affects SE to any extent, it is important to include age as a covariate when estimating effects of other employment characteristics on SE. Finally, as SE constitutes an integrative approach to functioning at work and on the labor market, research into the effects of age on SE provides broad insight into the relationships between age and a broad set of relevant occupational health variables. Thus, considering the relevance of age in the context of SE, our research question is: How does age affect SE and each of its dimensions?

Estimating the effect of age on sustainable employability

A major difficulty in assessing the effects of age on SE is that age effects can be distorted by time (in the literature predominantly referred to as “period effects”) and cohort effects. That is, when considering development in individual characteristics over time, three interrelated aspects of time are implicitly under study: age, time (ie, period), and cohort effects (36–40). Age effects concern the aforementioned changes in a variable that are due to aging (eg, on average, without any vision correction, 30-year-olds perform better on a vision test than 70-year-olds). Time effects are systematic differences between measurement moments that are not due to aging but rather some contextual conditions. That is, average scores on a variable could differ systematically between a first and a second measurement occasion (eg, on average, people’s stress levels are higher during an economic crisis than in a flourishing economy), and such differences could wrongly be ascribed to aging because as time passes age increases as well. Finally, cohort effects capture the effect of belonging to a specific generation regardless of age and time of observation (eg, people born in the 1950s might value organizational commitment more than those born in the 1980s). To avoid any bias in estimating the effects of age on sustainable employability, these three effects should ideally be estimated simultaneously in an Age-Period-Cohort model (APC).

Estimating APC models is problematic for two reasons. First, as argued by O’Brien (41), age, time and cohort effects are exactly mathematically confounded. Consequently, regressing a dependent variable on age, time, and cohort variables results in collinearity problems. Second, this first issue makes it impossible to achieve model identification of an unconstrained APC model (41). Although several researchers have developed approaches to handle these problems (eg, 38, 39, 42, 43), studies using empirical data (40) and simulations (42), but also logical arguments (43) suggest that APC models simply cannot be estimated without making assumptions that impose constraints. Therefore, researchers should carefully consider which constraints are theoretically reasonable given a certain research question.

Considering our research question, we constrain our approach by exploring age effects while controlling for time effects. As age is the main variable of interest in this paper it makes for an obvious candidate for inclusion. That is, we want to explore how age affects each of SE’s dimensions. Additionally, as time effects cover the specific conditions at a certain time point compared to those at another time point, they resemble broad differences in the employment context across time points, which is the main object of interest in predicting SE. Contrastingly, cohort is a fixed variable that can and does not change as time progresses. Therefore, when exploring the effects of age on SE, time effects (ie, how does age affect SE controlling for measurement moment?) are more interesting to control for than cohort effects (ie, how does age affect for year/period of birth?).

Methods

Sample

The analyses were performed using data from the prospective Maastricht Cohort Study (MCS). The ongoing MCS started in May 1998 as a large-scale longitudinal study on various relationships between aspects of work and the development of fatigue. At baseline (ie, 1998) it included 12 140 Dutch respondents, aged 18–65 years, working in 45 different organizations. All respondents provided written informed consent and data for all of the MCS waves were collected in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) and its later amendments (see 44, 45 for more information). The Medical Research and Ethics Committee of the Maastricht University Medical Centre approved the protocol for the MCS (MEC 08-4-032).

Specifically, data from the 2012 and 2014 measurement wave of the MCS were used. These waves were selected because they contained all of the self-report measures necessary for the analyses. Before exclusion, this dataset contained 4783 respondents in 2012 (1207 female, 3497 male, 85 missing), ranging in age from 34.6–79.0 [mean 57.6, standard deviation (SD) 8.4] years (N=4783). A total of 2111 respondents were excluded, either because they were not working at the time of survey completion, had more than one job, or exceeded the mandatory retirement age of 65 in 2014. These exclusion criteria were used because most of our main variables (ie, SE and its dimensions) were measured with instruments that make explicit reference to work and, in some cases, a single job. The latter could invite unusual interpretation of the items among people with multiple jobs and thereby invite biased responses. A total of 2672 respondents (829 female, 1781 male, 62 missing) ranging in age from 33.4–65.0 (mean 52.9, SD 6.6) years remained for inclusion in the analyses.

Instruments

The nine dimensions of SE (ie, perceived health status, need for recovery, fatigue, work ability, skill gap, employability, performance, motivation, and job satisfaction) were assessed using validated self-report questionnaires. See table 1 for an overview of all questionnaires. Importantly, as the study relied on existing data it also relied on the measures available in the dataset. Consequently, motivation and job satisfaction had to be operationalized with suboptimal instruments (ie, the motivation subscale of the Checklist Individual Strength and three work engagement items respectively). SE itself was constructed as a composite variable based on its nine dimensions (cf. 32, 35). That is, scores on all nine dimensions were standardized, coded in such a way that a high score on each dimension would indicate a positive contribution to SE, and then added with equal weighting. Age was captured as date of questionnaire completion minus self-reported date of birth. Finally, time was constructed by recoding the time of measurement (ie, 2012 or 2014) into a dichotomous variable where 2012 was coded to “1” and 2014 to “2”.

Table 1

Summary of scales used in analyses.

Analyses

The first part of the present study’s main analyses explored the effects of age on SE while controlling for time effects. These analyses consisted of ten separate multilevel regression models with age and time as independent variables and SE and each of its dimensions as single dependent variable. In these models, time of measurement (level one) was nested in participants (level two). Moreover, as two waves were included, time itself was included as a dichotomous variable. Additionally, age was included as a categorical variable with one-year categories (eg, every participant aged 35.0–35.99 years belonged to the age category “35”). Including one-year age categories was most elegant as, given our sufficiently large sample, it provided the optimal sensitivity for detecting non-linear age effects between any of the categories and in any direction, thus matching the explorative nature of our research question. Additionally, we opted for estimating ten separate models (ie, one for SE and one for each of its dimensions separately) because SE is a formative construct (35). The formative nature of SE implies that each of its dimensions may be affected by age and time differently, and that each dimension may have a different weight in SE depending on a participant’s occupation. Estimating the ten separate models enabled circumventing these issues while enabling the estimation of overall age and time effects on SE. Finally, for each of the ten, we estimated a fixed-effects only model, a random-intercept model and a random-intercept-random-slope model. The latter type of model allowed random slopes for the time variable only. This overall modeling approach enabled estimating both within (ie, time) and between (ie, age) subjects effects, while maintaining the optimal flexibility to match the explorative nature of this study. These analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 23 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and cross-checked with SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, BC, USA).

The second part of our main analyses consisted of ten separate repeated measures analyses of variance (ANOVA), which served to identify the relative percentages of within- and between-subjects variance in SE and each of its nine dimensions over the two times of measurement. These analyses were performed as, regardless of the magnitude and direction of the age and time effects in the first part of the main analyses, it is instrumental to establish the magnitude of the within-subjects variance over time. That is, low within-subjects variance over time would reduce the feasibility of modelling SE as a time dependent construct. These analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 23.

The main analyses were supplemented with three additional types of analysis. First, as the main analyses used data from later waves of the MCS (ie, 2012 and 2014), we checked whether our findings regarding the age effect were consistent with results of the same analyses using data collected in the earlier waves of the MCS. To this end, we estimated the same multilevel regression models as mentioned above, but now with a total of seven time points (ie, starting with the first wave of the MCS in 1998 to the most recent wave in 2014). However, as only three SE dimensions were included in these earlier waves, these analyses were restricted to the dimensions of perceived health status, need for recovery, and fatigue. Second, we analyzed whether drop-out of participants in these same earlier waves of the MCS was related to age, employment status and health to rule out (self-) selection bias. And third, using MCS data from the 2012 and 2014 waves, we estimated multilevel regression models with mild and heavier physical functioning impairments as dependent variable (ie, instead of SE and its dimensions) and age and time of measurement as independent variables. These latter analyses were performed to see if our data would reveal regular age-related impairments in general physical functioning, unrelated to functioning at work.

Results

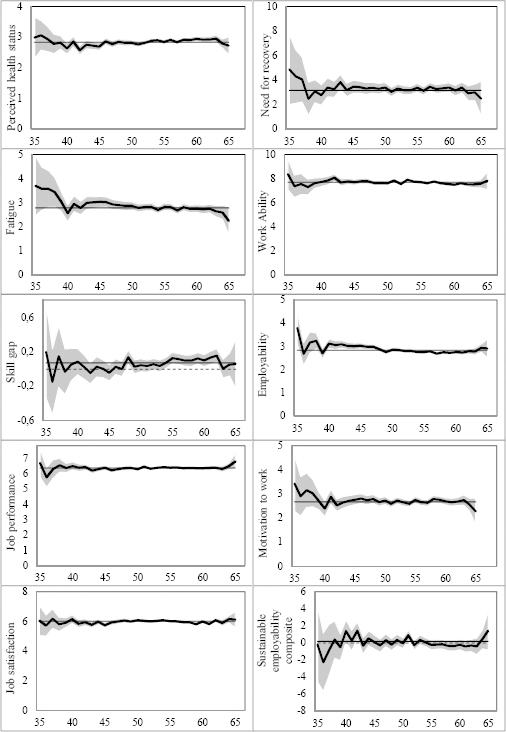

The main analysis revealed mixed result patterns for SE and each of its dimensions. First, the multilevel regression models revealed that of SE’s nine dimensions only perceived health status and employability were significantly affected by age (table 2). The overall SE construct was not affected significantly by age. For parsimonious reporting of results, estimated marginal means of SE and each of its dimensions are plotted per age group in figure 1 to illustrate age effects. As can be observed from these graphs, the age effects on perceived health status and employability were, although significant, small. That is, for perceived health status, the largest estimated marginal mean difference between two age groups was 0.49 while the overall SD was 0.75. Similarly, for perceived employability the largest difference (1.13) was only slightly higher than the SD (0.80). These differences in estimated marginal means might be inflated due to the lower number of participants in the age categories on which the differences were based [ie, the lower ages have wider confidence intervals (CI), see figure 1]. Additionally, time significantly affected fatigue (β=0.09, t(2, 579)=3.20, P<0.001, 95% CI 0.035–0.145), job performance (β=0.084, t(2, 475)=3.31, P=0.001, 95% CI 0.034–0.134), and skill gap (β=0.093, t(2, 454)=6.44, P<0.001, 95% CI 0.064–0.121). The overall SE construct was not affected significantly by time of measurement. Table 2 provides an overview of results regarding overall significance tests of age and time effects on SE and its dimensions. Second, the repeated measures ANOVA revealed that the within-between subjects variance ratios differed per dimension of SE. For all dimensions and SE itself, most variance exists between (61.4–85.0%) rather than within (15.0–38.6%) subjects (table 3).

Table 2

Overview of overall significance tests of age and time effects controlled for each other on sustainable employability and each of its aspects.

| F | P-value | df numerator | df denominator | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | ||||

| Perceived health status | ||||

| Age | 1.65a | 0.015 | 30 | 3320 |

| Time | 0.61 | 0.435 | 1 | 2713 |

| Need for recovery | ||||

| Age | 0.62 | 0.945 | 30 | 2974 |

| Time | 0.38 | 0.540 | 1 | 2575 |

| Fatigue | ||||

| Age | 1.25 | 0.165 | 30 | 3340 |

| Time | 10.24b | 0.001 | 1 | 2676 |

| Workability | ||||

| Age | 1.30 | 0.129 | 30 | 3479 |

| Time | 2.19 | 0.139 | 1 | 2387 |

| Skillgap | ||||

| Age | 1.27 | 0.152 | 30 | 3407 |

| Time | 41.51b | <0.001 | 1 | 2405 |

| Perceived employability | ||||

| Age | 2.89b | <0.001 | 30 | 3323 |

| Time | 0.28 | 0.597 | 1 | 2482 |

| Job performance | ||||

| Age | 0.81 | 0.764 | 30 | 3550 |

| Time | 10.97b | 0.001 | 1 | 2443 |

| Motivation | ||||

| Age | 1.03 | 0.427 | 30 | 3396 |

| Time | 0.09 | 0.759 | 1 | 2637 |

| Job satisfaction | ||||

| Age | 1.05 | 0.392 | 30 | 3055 |

| Time | 0.64 | 0.425 | 1 | 2513 |

| Sustainable employability composite | ||||

| Age | 1.17 | 0.227 | 30 | 2908 |

| Time | 1.46 | 0.241 | 1 | 2401 |

Table 3

Overview of within- and between subjects variance in sustainable employability and each of its dimensions based on repeated measures ANOVA with over two points in time. [SS=sum of squares; m=model; r=random; w=within subjects; b=between subjects; t=total].

Figure 1

Estimated marginal means of sustainable employability and each of its dimensions (vertical axis) for all age groups (horizontal axis; in 1 year categories), including 95% confidence intervals, overall mean line (straight), and zero-line (dashed).

The supplemental analyses revealed similar patterns for the available dimensions (ie, perceived health status, need for recovery, and fatigue) of SE in earlier waves of the MCS. Additionally, drop-out of participants from the cohort was only minimally related to age but not health. That is, from the first (1998) to the third (1999) wave of the MCS, a relatively larger number of mainly young participants (aged 18–25 years) chose to no longer participate in subsequent waves. However, in subsequent waves no further age-related drop-out was observed. Finally, the multilevel regressions with mild and heavier physical functioning impairments as dependent variables revealed that mild physical functioning impairments were related to age and heavy physical functioning impairments were not. For parsimonious reporting, specific results of these supplemental analyses are not reported here but can be requested from the corresponding author.

Discussion

The present paper aims to explore the relationship between age and sustainable employability (SE) while correcting for potential time effects. In line with previous literature on age as a predictor of functioning in work, we show that SE is only marginally affected by age. Specifically, only two SE dimensions (ie, perceived health status and employability) demonstrate significant, albeit small associations with age. Additionally, we find time effects on three SE dimensions (ie, fatigue, job performance and skill gap). Moreover, a substantial amount of within-subjects variance is observed in SE dimensions over a timespan of two years, with differing within-between subjects variance ratios across dimensions. These findings suggest that it is feasible to consider SE as a time-dependent construct in which sustainability is captured as development over time (cf. 32). Additionally, the prominent role ascribed to age in SE research may require reconsideration.

Limitations

A first potential limitation to the present study concerns generalizability. Although the sample includes employees with a large variety of job titles, employees facing the highest category of physical demands as part of their job are underrepresented. That is, only two employees in the sample could be considered to belong to this category. Therefore, our findings may not generalize to this specific group of employees (eg, those in the building trade), who are at higher risk of early labor market withdrawal (46). Nonetheless, based on job type the sample in this study does seem representative for at least 80% (47) to 98% (48) of the Dutch employees who do not work under the highest physical demands. Similarly, our findings may arguably not generalize to the self-employed [about 16.6% of the Dutch working population (49)] or those working in small businesses [about 34% of the Dutch working population (50)]. However, the actual job demands self-employed and small-business employees face are not necessarily different from those of employees employed in larger organizations. Relatedly, the findings may not generalize to people with multiple jobs as these were excluded from our sample. However, the exclusion of this group is not likely to have impacted our findings as they constituted only a small part of the initial sample. Still, future studies should look into age and time effects on sustainable employability for these specific groups.

A second potential limitation lies in the reliance on self-report measures. When completing self-report measures on, for example performance and health, employees may use their same age peers as reference points (51). This potential comparison to others could result in slightly biased findings. However, there is no way of estimating the magnitude of this bias as no viable alternatives to self-report questionnaires for studying the complex topic of SE in field settings are currently available, and the approach of using self-report questionnaires is common practice. Relatedly, since the study uses existing data, two of the measures used (ie, motivation to work and job satisfaction) are not ideal. That is, the measures for these constructs are commonly used to measure general motivation to engage in activities and work engagement respectively. This general motivation could be a proxy for motivation to work (ie, working is a core activity in most working individuals’ lives), but is not a perfect measure. Similarly, the work engagement items used to capture job satisfaction do measure a general appreciation individuals have for their work, but not job satisfaction itself in full specificity. However, no alternative measures for these constructs were available in the dataset and no other datasets with superior measures and an equally good sample could be identified. As such, we deemed it better to use these proxies for motivation to work and job satisfaction than to not include these dimensions at all. Nonetheless, future research on SE might benefit from developing alternatives to self-report data and use measures that target all SE dimensions with full specificity.

Third, the present study’s scope is entirely on age and time effects. Although many candidates may exist, the study does not report on any explanatory variables or alternative predictors. For example, chronic diseases might explain part of the age effects found in this study (33). Similarly, education level, socio-economic status and several other variables could predict SE. This study deliberately did not include such variables because age is so strongly assumed to be important in the context of SE that it requires a separate treatise. Additionally, including such variables would not affect the main conclusion of our article (ie, age is not as important as assumed), as they would only reduce the variance that age could explain (ie, age effects would be even smaller). Finally, age and time are givens and unchangeable, and thus, precede – or at least coincide with – any other variable in causal chains in the context of SE. By teasing these two effects apart without including other potential covariates, the present paper may pave the way for future studies on other predictors of SE and their potential interactions with age.

Finally, some caution is advised in interpreting this study’s findings for three reasons. First, absence of evidence does not equal evidence of absence. Although we find only limited effects of age on SE, we do not intend to contend that age is (nearly) irrelevant in the context of SE (eg, age may still be an important moderator of other employment characteristics). Still, it should be noted that, if anything, our analyses left plenty of room for age effects to emerge (ie, we could have controlled for correlation among dependents to reduce the age effects further and we liberally used age as a categorical variable). Thus we can conclude that, in our sample, age effects are minor indeed. Nonetheless, it remains impossible to prove that something – here age effects on SE in particular – does not exist. Second, our findings could arguably be biased by selection effects. We examined this by estimating age and time effects both for the available (predominantly health-based) constructs in earlier waves of the MCS and for general and severe physical functioning impairments in the current waves, as well as by considering age, health and employment status related attrition. As we find similar patterns in earlier waves, the expected general – but not severe – physical functioning impairments with age, and no indications of age, health, or employment status related attrition, these auxiliary analysis give no indication of selection effects. Moreover, based on the large variety of employees from various organizations across multiple sectors in our sample, it seems representative for Dutch employees (except for those in highly physically demanding jobs, and, arguably, those who are self-employed or working in small businesses). Third, one could argue that our study should include more measurement waves covering a larger timespan. This might indeed be favorable, but would mainly increase the likelihood of finding time – and not age – effects on SE. In conclusion, we advise some caution when interpreting our finding that age has only limited effects on SE, but given the aforementioned considerations we deem it unlikely that in a larger population more pronounced (direct) age effects would emerge. Nonetheless, we encourage other researchers to replicate our findings to see if age remains a modest predictor of SE in different samples covering larger timespans.

Implications

First, our findings imply that the focus on older employees as being less capable to function at work in the context of SE does not seem justified. As only two SE dimensions are significantly affected by age, these two effects are small and the overall construct of SE is not significantly affected by age, older employees do not seem less able to function at work and on the labor market. This echoes ideas from previous studies that document minor, no, or positive relationships between age and functioning at work (24–26, 52). Perhaps the notion that older employees would be less able to function at work or in the labor market is merely based on existing stereotypes (22), or meaningful declines in work-relevant characteristics only begin once people stop using them (eg, after retirement) (53, 54). Alternatively, our findings may suggest that despite cognitive and physical declines in some areas, older employees have excellent compensation strategies or their jobs are well adjusted to their needs and abilities (55, 56). Either way, our findings seem to suggest that the attention SE research and policy have directed to mainly older employees is not proportional. Instead, SE should be considered as an affair that is relevant across the lifespan (31, 32) and this message should be communicated to policy-makers, managers, and human resource professionals. Moreover, it seems advisable to offer human resource management practices regardless of age (57) and, appreciating the variance within age groups, to design them to match individual employees’ needs rather than the stereotypical needs of certain age groups.

Second, our findings suggest that modeling SE as a time-dependent construct is viable. Fleuren et al (32) propose that the sustainability component of SE can be modeled as development in SE and its dimensions over time. However, if no within-person variation over time would exist or if SE would be largely or completely determined by age, considering developmental trajectories would make little sense. By demonstrating that age only plays a minor role in the context of SE and SE dimensions exhibit substantial variation over time (changes occur over a period as short as two years), we show that this approach to SE is feasible. Relatedly, the differences in development and the extent to which each SE dimension is affected by age reconfirm SE’s nature as a formative construct (35). Therefore, in addition to the message that SE does not strongly decline with age, our findings suggest that recent developments in conceptualizing SE are promising.

Finally, the time effects in this study may point to the effects of the financial crisis that started in 2008 and their backlash on employees and the labor market. As the data used in our study were collected in 2012 and 2014 respectively, and we find concurrent overall increases in fatigue, skill-gap and job performance, our findings may reflect an impact of the financial crisis on employees. These overall increases could point to employees having to work harder, potentially to secure their job (ie, on average performance but also fatigue increases), while having reduced access to development opportunities (ie, on average skill gap increases). Alternative explanations of these time effects might be relevant as well, such as a requirement for people to remain working while being diagnosed with a chronic disease (58). However, if because of a structural change, a larger percentage of the working population would consist of people with chronic diseases, one would expect average health and functioning scores to differ structurally before and after the change. In our study, we did not find such time effects on most health variables, so the requirement to work longer with chronic diseases is a less plausible explanation of our findings.

In conclusion, this paper contributes to the literature by providing insights in age- and time effects on SE. By identifying only modest age effects and substantial variation in SE and its dimensions over two time points, the paper demonstrates the feasibility of modeling SE as the inherently time-dependent construct it is. Moreover, these fundamental insights in the age-time-SE relationships loosen the firm grip the age-issue has kept on SE research. Thereby, this paper may contribute to countering the negative stereotyping of older employees as well as form a prerequisite for more practice-oriented research on dynamic employment characteristics as predictors of SE. After all, the main goal of SE research is to identify work and work-contextual factors that may facilitate people in participating in employment longer in a beneficial way.