Part-time sick leave is used in all Nordic and some European countries to enable continued working when health reasons prevent full-time work (1, 2). Part-time return to work (RTW) supported by partial sickness benefit has in many studies resulted in enhanced return to full-time work and reduced sickness absence (SA) in the long term (3–8). We are not aware of studies looking at the economic aspects of part-time sick leave.

The legislative framework for the use of part-time sick leave differs between countries. In most Nordic countries, part-time sick leave is used to compensate for the proportional loss of work ability, and the sickness benefit will, respectively, range from a few to close to 100 percent of full sickness benefit. In Finland, however, part-time sick leave is a voluntary option for those who have been assessed by a physician to be incapable of performing their full duties, but are able to work 40–60% of full time. The partial sickness benefit is always set at 50% of full benefit. The application for the benefit is made jointly by the employer and the employee and granted by the Social Insurance Institution (SII). Part-time sick leave was introduced in Finland as late as 2007, and in 2010 the criteria for its use were widened.

Earlier we carried out a quasi-experiment looking at the effectiveness of the use of part-time sick leave at the early stage of work disability due to a musculoskeletal disease or mental disorder. During the two-year follow-up, the proportion of time at work was higher and sick leave and disability retirement lower among those who had had part-time sick leave compared with those on full-time sick leave. In the former group, the proportion of those with full disability retirement was about a third of those in the latter group (9).

In the current paper, we compare the accumulation of social security costs during two years between recipients of partial and full sickness benefit.

Methods

We utilized a 70% random sample of the working age population in Finland on 31 December 2010. Data on compensated SA, with dates and diagnoses, were obtained from the SII. The Finnish Centre for Pensions (FCP) provided information on disability and other retirement, employment, and unemployment periods. Information on vocational rehabilitation periods was obtained from both SII and FCP. Demographic information and information of annual earnings, unemployment benefits and pension benefits were provided by Statistics Finland. Data were linked with social security numbers and provided to the researchers in unidentifiable form.

In Finland, the SII compensates SA after a so-called employer period of ten full SA days. Before 2010, part-time sick leave was available only for persons with a preceding full SA of 60 compensated days. The legislation was changed in 2010, enabling the use of part-time sick leave already from the first compensated day. Still, about 80% of recipients of the partial sick leave benefit at an early stage have a preceding compensated full-time sick leave period. We therefore chose the participants among those with a preceding full SA. Because about 70% of part-time sickness absences are prescribed due to a musculoskeletal disease or mental disorder (10), we further limited our study population to these two disease groups.

As described in our previous paper (9), there were a total of 1879 persons, who during a two-year recruitment period (1 January 2010–31 December 2011) had part-time sick leave due to a musculoskeletal disease or mental disorder, immediately following a continuous full-time SA of 1–59 compensated days. For each case with part-time sick leave, a control was selected among those who had a full-time sickness absence period continued with another full-time sickness absence. Propensity score matching was carried out within the four diagnostic group × gender strata to make the part-time and full-time groups comparable regarding sociodemographic factors (age, major region, employment sector, industrial sector, socioeconomic status, annual gross income in the year preceding the SA, number of days being employed or unemployed during the preceding two years) and the number of preceding SA days. This resulted in 1878 persons with part-time sick leave matched with 1878 controls with full-time sick leave. All participants were followed for two years. The complete register information enabled us to assess the “work participation status” for each participant for each follow-up day. Overall, we considered seven work participation statuses: (i) at work, (ii) full-time SA, (iii) partial work disability (including part-time sickness absence and partial disability retirement), (iv) receiving vocational rehabilitation benefit, (v) unemployed, (vi) full disability retirement, and (vii) other (outside labor force, status not known). Persons with partial work disability were considered to be working 50% of their working time.

The primary outcome for the present study was the difference in social security costs between the part-time (intervention) and full-time (control) sick leave group, expressed in absolute and relative values. We looked at the distribution of the costs of the different types of the benefits separately for the first and second follow-up year. We used percentile bootstrapping method with 5000 intervention–control pairs to estimate 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the relative difference in the costs (10). Due to a skewed distribution and a wide range of the costs, we also used the bootstrapping method to estimate the 95% CI for the difference in the mean costs per person per year.

The costs of the examined social security benefits were calculated as follows: the cost of a compensated full-time SA day was assessed for each person based on the person’s earned income total in state taxation for the preceding year in question using year-specific formulae provided by the SII (11–14). The cost of a compensated part-time SA day was calculated as 50% of a full-time sickness absence day. The cost of vocational rehabilitation benefit day was estimated as annual mean cost paid by the Finnish Centre for Pensions (15–18). The cost of an unemployment day was calculated based on the person’s unemployment income and number of unemployment days for the year in question. The cost of a day on retirement (including work disability, old-age, and other) was calculated based on the person’s pension income for the year in question (total pension income from all types of pensions for each group member, provided by Statistics Finland).

We looked at the cost difference in the entire study group and for the two diagnostic groups by gender. We further stratified by age group and selected industry. A preliminary scrutiny identified a few persons with very high unemployment or retirement costs (one in part- and five in full-time sick leave group). We carried out a sensitivity analysis of the total costs where we removed these six persons and their matched pairs.

Results

During the two-year follow-up, the number of full-time SA days was lower and both the part-time SA days and the overall SA costs were higher in the intervention than the control group (table 1). In total, about €9 million less social security costs were observed in the intervention compared with the control group, resulting in a cost ratio of 0.512 (95% CI 0.511–0.513) and a cost difference of -€2395 (95% CI -2890– -1899) per person per year. Apart from SA, the highest costs in both groups were due to retirement and vocational rehabilitation, however, the absolute difference in costs was highest for retirement and the relative difference highest for vocational rehabilitation.

Table 1

Total number of days on ill-health-related, unemployment and retirement benefits, their social security costs (€) and relative cost differences (cost ratio) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) during two years of follow-up in the intervention (N=1878) and control group (N=1878). Cost distribution (%) of the benefits during the first and second follow-up year in the intervention and control group. [SA=sickness absence.]

| Number of pairs | Total number of days | Total costs (€) | Cost ratio (95% CI)a | Cost distribution (%)b | Cost distribution (%)b | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Intervention | Control | |||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | 1st year | 2nd year | 1st year | 2nd year | |||

| All | 1878 | |||||||||

| Full-time SA | 67 148 | 94 061 | 4 253 626 | 5 541 539 | 0.768 (0.767–0.769) | 23.8 | 15.2 | 23.8 | 6.5 | |

| Part- time SA | 61 897 | 1718 | 2 176 746 | 62 901 | 35.94 (35.74–36.15) | 26.2 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.2 | |

| Vocational rehabilitation | 9626 | 65 569 | 688 098 | 4 478 926 | 0.154 (0.153–0.155) | 0.6 | 4.8 | 9.1 | 12.5 | |

| Unemployed | 25 137 | 42 853 | 494 567 | 1 803 257 | 0.275 (0.274–0.279) | 1.9 | 8.7 | 5.3 | 7.7 | |

| Retiredc | 62 651 | 133 778 | 1 753 386 | 6 474 449 | 0.272 (0.271–0.273) | 4.0 | 14.3 | 13.9 | 20.0 | |

| Total | 9 366 423 | 18 361 072 | 0.512 (0.511–0.513) | 56.6 | 43.4 | 53.1 | 46.9 | |||

| Musculoskeletal diseases (men) | 233 | |||||||||

| Full-time SA | 7922 | 11 717 | 537 460 | 744 026 | 0.725 (0.722–0.727) | 21.8 | 16.6 | 22.2 | 6.8 | |

| Part- time SA | 6645 | 110 | 242 542 | 5113 | 50.75 (49.65–51.85) | 25.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | |

| Vocational rehabilitation | 1141 | 6526 | 96 995 | 540 814 | 0.199 (0.194–0.203) | 1.1 | 5.0 | 8.2 | 11.4 | |

| Unemployed | 3384 | 6362 | 40 309 | 679 220 | 0.125 (0.119–0.130) | 1.6 | 9.1 | 7.5 | 5.7 | |

| Retiredc | 8958 | 15 813 | 291 192 | 825 464 | 0.367 (0.364–0.370) | 4.0 | 15.6 | 14.0 | 24.0 | |

| Total | 1 208 498 | 2 794 637 | 0.444 (0.441–0.446) | 53.6 | 46.4 | 51.9 | 48.1 | |||

| Musculoskeletal diseases (women) | 793 | |||||||||

| Full-time SA | 29 902 | 40 421 | 1 761 137 | 2 303 463 | 0.764 (0.763–0.766) | 26.1 | 15.2 | 27.9 | 8.3 | |

| Part- time SA | 26 651 | 619 | 876 106 | 20 745 | 46.98 (46.48–47.48) | 24.2 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.3 | |

| Vocational rehabilitation | 2756 | 19 921 | 179 930 | 1 274 655 | 0.146 (0.145–0.148) | 0.2 | 3.2 | 7.7 | 9.8 | |

| Unemployed | 9049 | 13 978 | 297 344 | 428 834 | 0.875 (0.848–0.902) | 2.3 | 8.9 | 4.8 | 6.9 | |

| Retiredc | 30 425 | 51 629 | 691 045 | 2 171 120 | 0.323 (0.321–0.324) | 4.3 | 15.5 | 13.0 | 20.5 | |

| Total | 3 805 562 | 6 198 817 | 0.618 (0.616–0.620) | 57.0 | 43.0 | 54.2 | 45.8 | |||

| Mental disorders (men) | 188 | |||||||||

| Full-time SA | 7087 | 8954 | 520 247 | 626 214 | 0.840 (0.837–0.844) | 19.4 | 16.5 | 19.2 | 5.5 | |

| Part- time SA | 5623 | 63 | 238 544 | 3486 | 67.83 (66.53–69.12) | 24.7 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.1 | |

| Vocational rehabilitation | 1921 | 8898 | 164 108 | 734 829 | 0.235 (0.231–0.238) | 1.3 | 9.4 | 11.5 | 14.9 | |

| Unemployed | 3949 | 6591 | 48 490 | 184 902 | 0.335 (0.328–0.342) | 1.7 | 8.3 | 2.9 | 11.2 | |

| Retiredc | 5231 | 14 736 | 248 089 | 967 552 | 0.269 (0.266–0.272) | 4.2 | 14.2 | 15.7 | 18.4 | |

| Total | 1 219 478 | 2 516 983 | 0.491 (0.488–0.493) | 51.4 | 48.6 | 50.0 | 50.0 | |||

| Mental disorders (women) | 664 | |||||||||

| Full-time SA | 22 237 | 32 969 | 1 434 782 | 1 867 836 | 0.770 (0.768–0.771) | 21.8 | 16.6 | 22.2 | 6.8 | |

| Part- time SA | 22 972 | 926 | 819 554 | 33 557 | 26.46 (26.22–26.70) | 25.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | |

| Vocational rehabilitation | 3809 | 30 224 | 247 065 | 1 928 628 | 0.129 (0.128–0.130) | 1.1 | 5.0 | 8.2 | 11.4 | |

| Unemployed | 8755 | 15 922 | 108 424 | 510 301 | 0.185 (0.182–0.188) | 1.6 | 9.1 | 7.5 | 5.7 | |

| Retiredc | 18 038 | 51 600 | 523 060 | 2 510 613 | 0.212 (0.211–0.213) | 4.0 | 15.6 | 14.0 | 24.0 | |

| Total | 3 132 885 | 6 850 635 | 0.459 (0.458–0.460) | 53.6 | 46.4 | 51.9 | 48.1 | |||

Costs were saved by the intervention in both diagnostic groups among both men and women, however, cost savings were lower for women compared with men, especially among those with musculoskeletal diseases (table 1). The largest relative savings emanated from vocational rehabilitation costs in each matched gender × diagnosis group, except men with a musculoskeletal disease, for whom the reduction in unemployment costs was the largest.

Social security costs were higher during the first compared with the second follow-up year in both intervention and control group (table 1). The share of full-time and part-time SA costs combined was the highest during the first follow-up year (23.8% + 26.2% in intervention and 23.8% + 0.9% in control group). During the second follow-up year, the share of SA costs continued to be the highest in the intervention group, whereas the share of retirement costs became predominant in the control group. Vocational rehabilitation contributed considerably less to the costs in the intervention than the control group both during the first and second follow-up year. Also unemployment contributed less to the costs in the intervention compared with the control group during the first follow-up year. Overall, relative savings were higher for the second compared with the first year (table 1, footnote a).

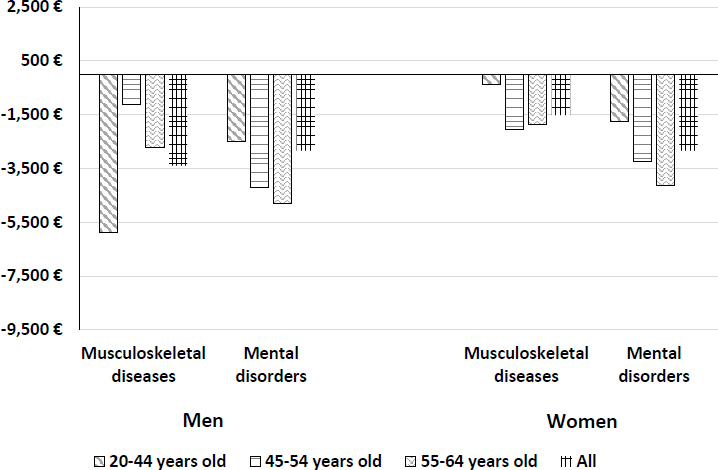

The average cost difference per person per year was around -€3000 in the matched gender × diagnosis groups, except in women with a musculoskeletal disease, for whom the difference was about -€1500 (figure 1a and appendix table A, www.sjweh.fi/show_abstract.php?abstract_id=3780). Further subgroup analyses showed that in mental disorders, savings increased linearly with age in both genders. Overall, the savings were largest for 20–44 year-old men with a musculoskeletal disease and smallest for women in the same age and diagnostic group.

Figure 1a

Mean differences in total social security costs per person per year (€) between the intervention and the control group by gender, diagnostic group and age group.

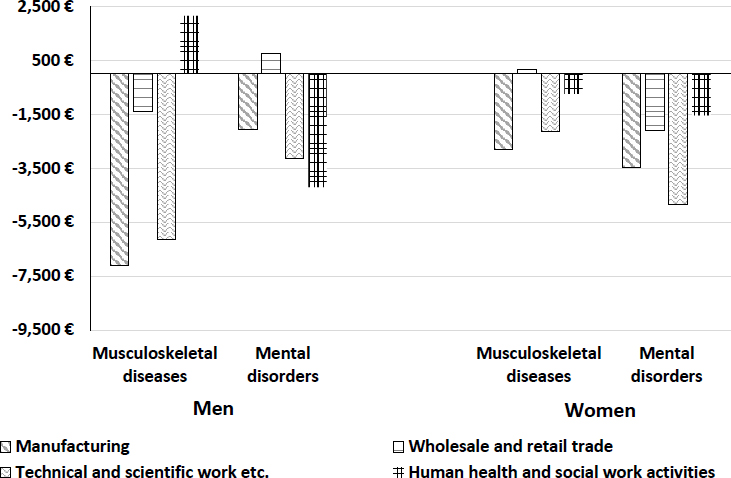

Among selected industrial sectors, cost savings were seen in manufacturing and in technical and scientific work in all gender × diagnosis groups. However, the difference in costs showed an inconsistent pattern in wholesale and retail trade as well as in human health and social work activities. In the latter sector, among men with musculoskeletal disease, the intervention resulted in an increase in social security costs (figure 1b and appendix table A).

Figure 1b

Mean differences in total social security costs per person per year (€) between the intervention and the control group by gender, diagnostic group and selected industrial sector.

The sensitivity analysis, excluding a few subjects with very high unemployment or retirement costs, showed total costs of €9.1 million in the intervention and €17.3 million in the control group, resulting in a cost ratio of 0.527 (95% CI 0.526–0.528).

Discussion

The current study provided an analysis of social security costs based on our previous quasi-experiment on the effects of part-time sick leave on work participation (9). We looked at what the social security cost difference would be during a two-year period if part-time sick leave was used instead of full-time sick leave to recover from a musculoskeletal disease or mental disorder. Our analysis within nationally representative register data showed that the use of part- instead of full-time sick leave at the early stage of work disability saved about half of all ill-health-related, unemployment and retirement costs during two years. The largest savings were attributable to differences in the costs of retirement and vocational rehabilitation. The savings were higher for the second compared with the first follow-up year.

Costs were saved in musculoskeletal diseases and mental disorders among both men and women, however, costs savings for women with a musculoskeletal disease were lowest. The savings increased linearly with age among both men and women with a mental disorder, however, there was no consistent pattern according to age among those with a musculoskeletal disease. The savings varied according to major industrial sector, being largest in manufacturing and technical and scientific work.

The strengths of this study are the nationally representative data where we had extensive information on social security benefits paid to the participants. A limitation was that, even though we could estimate the costs with a reasonable accuracy, the approximation may have affected the absolute values of the costs. Moreover, we assessed the costs from a social security perspective only and had no information on the costs of the employer in organizing part-time work and replacement for part-time or full-time SA that would have been necessary for a full economic analysis (19, 20). By using the propensity score, we attempted to minimize selection bias between the intervention and control group and achieved a good comparability between the groups with regard to the variables included in the propensity score (9). It is still possible that the groups were selected according to factors on which we had no information, eg, the individual’s motivations regarding working (21).

In conclusion, we found that part- instead of full-time sick leave, at the early stage of work disability due to musculoskeletal diseases or mental disorders, leads to considerable social security cost savings during two years, in correspondence with increased work participation (9) and in addition to earlier reported health benefits (5). This study shows that part-time sick leave can be recommended also from an economic perspective; however, more consideration should be given to women with musculoskeletal diseases as well as employees in human-health and social-work activities.