Smoking is one of the biggest public health threats; worldwide it kills more than seven million people yearly (1). First-hand smoking causes many different types of cancer, including lung, mouth and throat, stomach, liver, kidney and colorectal cancer, and leukemia. Furthermore, smoking can cause stroke, coronary heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes, blindness, asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, and reduced fertility (2). Finally, smokers are more likely to experience a mental illness compared non-smokers (3). Therefore, smoking poses a significant societal burden, which can be expressed in terms of both healthcare costs and lost work productivity (4). Productivity loss could be caused by sickness absence, presenteeism, work disability, or death.

A wide range of studies have been performed to study the association between smoking and productivity (5). In 2013, a systematic review on the association between smoking and sickness absence was published. From this review, it was concluded that smoking increased the risk of sickness absence and number of sickness absence days (5). However, the generalizability of this systematic review to a general working population was limited since the authors included studies with specific samples of participants who were already predisposed to high levels of sickness absence, such as workers with severe pain (6) or diabetes mellitus (7), and studies that only examined sickness absence due to specific conditions, such as airway infections (8) and back pain (9–11). Furthermore, an updated review on this topic could be of added value, since several new studies have been published in the meantime (12–15).

Clear evidence on the impact of smoking on sickness absence, especially evidence that can be translated to a wide variety of populations and workplace settings, could encourage employers to promote smoking cessation among their employees. Promoting smoking cessation at the workplace can be highly effective from a public and occupational health perspective since the occupational setting has the potential to reach large groups of people, have higher intervention participation rates compared to other settings, and encourage peer-support and positive peer pressure (12). Furthermore, several effective workplace smoking cessation interventions have been proven effective, such as group behavior therapy, individual counselling, nicotine replacement therapy (NTR) provision, comprehensive programs (12), and financial incentives (13). Therefore, it is important to review systematically the available evidence regarding the association of smoking and sickness absence from a general working population perspective.

We aimed to (i) summarize the evidence on the extent to which smoking influences sickness absence in the working population by performing a systematic review and meta-analysis on this topic and (ii) determine whether effect sizes are different across sources of variation in study design, methodology, and population characteristics.

Methods

Search strategy and study selection

This systematic review has been a-priori registered and was executed according to PRISMA statement guidelines (14). In February 2018, a systematic literature search was conducted in PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane library. Search terms were related to: (i) exposure, ie, smoking, (ii) outcome, ie, some measure of work-related productivity1, and (iii) setting, ie, the workplace. Furthermore, in order to restrict our reference screening to a more manageable number of references (from 9812 to 1291), we added an additional part that consisted of search terms related to costs, long-term implications or effects, and economic, social or occupation burden. In order to ensure that we did not miss any relevant studies, we preselected 20 studies that we definitely wanted to include in our review. Of these, 19 were retrieved by using the current search strategy. The one study that was not retrieved did not have a term related to smoking in either title, abstract or keywords, and was therefore also not retrieved by the wider search. The search terms used for each of the databases can be found in the supplementary data (www.sjweh.fi/show_abstract.php?abstract_id=3848, table S1). Records retrieved from the different databases were combined and duplicates were removed.

Two reviewers independently screened 20% of the retrieved records on title and abstract using the Rayyan online tool (rayyan.qcri.org). Articles had to fulfill all of the following inclusion criteria in order to be included. First, an article was eligible if the sample consisted of adults with a paid job in any occupation. Second, articles had to report on smoking status, based on self-reports, employee records or biomarkers, and to include both current smokers and current non-smokers in order to compare these groups. Articles only reporting information on passive smoking were excluded. Third, an article had to report on sickness absence. Fourth, we included all types of study designs, as long as the article reported on empirical data. Fifth, articles were included only if they had been published in the last 25 years, since there have been substantial changes in employment relations and social benefit systems, and thereby in determinants of sickness absence. Sixth, only articles written in English and published in peer-reviewed journals were included.

In total, the two reviewers had 17 conflicts while screening 500 titles and abstracts. Discrepancies regarding in- and/or exclusion were discussed and the criteria were adjusted accordingly. To the second criterion, we added that articles using proxies of smoking status, such as having a smoking associated disease (eg, COPD or pulmonary cancer), should be excluded. To the fourth criterion, we added that simulation studies that made assumptions regarding smoking prevalence or the impact of smoking on work-related productivity should be excluded. Finally, we added as a seventh criterion, that articles only reporting on specific subsamples of employees with certain diseases or disabilities should be excluded.

After reaching agreement, the first author screened the remaining 80% of the retrieved records only on title and abstract. Fulltext articles were retrieved for the selected records, which two reviewers screened. Discrepancies between reviewers were discussed until consensus was reached. Finally, references of relevant systematic reviews and the included articles were checked for additional articles and screened by two reviewers for eligibility.

Data extraction and quality assessment

A data extraction sheet was developed, pilot tested on ten randomly selected included articles and then refined. After finalizing the data extraction sheet, one reviewer performed the initial data extraction for all included articles and a second reviewer checked all proceedings. Per study, the following data were extracted: author, publication year and country, study sample (including dataset/cohort/register, number, gender, age), design (type and follow-up period), statistical method, assessment of smoking status, smoking prevalence, assessment of sickness absence, and the relation between smoking and sickness absence [eg, risk ratio (RR), odds ratio (OR), hazard ratio (HR)]. Corresponding authors were asked for additional information in cases where data provided in the published articles were insufficient. Two reviewers independently performed the quality assessment using a pilot tested set of ten predefined criteria (supplementary table S2). A quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies (15) and a review on the quality of prognosis studies (16) were used to formulate the criteria for the quality assessment.

Data analysis

Included studies were described based on the extracted data and methodological quality. In cases where multiple articles reported on results from the same study, only complementary information from the various articles was used for further analysis. In our statistical pooling, we differentiated between studies that reported on a dichotomous outcome measure where effect sizes were expressed in a measure of relative risk (eg, OR, RR, HR), and a continuous outcome measure, which were standardized into mean difference in sickness absence days per year (assuming 8 working hours per day and 40 working hours per week). We assumed that for measures of relative risk, several effect estimates (eg, OR, RR and HR) could be interpreted equally, even though OR overstate the effect size if interpreted as a relative risk, especially if prevalence is high (17). For some studies only an excess of missed workdays for smokers compared to non-smokers was reported. For these studies, to calculate the standardized mean difference, we counted the excess number of missed workdays as the total number of missed workdays for smokers, and thereby assumed that the number of missed workdays for non-smokers was 0 with a standard deviation of 1. If multiple outcomes were reported on in one study, but participants were not mutually exclusive, for example when short-and long-term absence were reported separately while participants could be included in both categories, then a weighted average effect size was calculated. If an article reported on outcomes separately for ex- and non-smokers, we only used the latter effect size. If an article distinguished between different categories of smoking exposure (eg, heavy, light, or incidental smokers), we calculated a weighted average effect size. If it was not possible to convert the study outcome to either a relative risk of sickness absence or a number of sickness absence days per year, then the study findings were only described narratively.

Exposure−outcome associations of individual studies, expressed in relative risk and mean difference were pooled using Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.3. Pooled exposure−outcome associations, derived from a random effects model, were presented in a forest plot. In a meta-regression, the results expressed in relative risk of sickness absence were stratified based on eight characteristics, which were defined a-priori based on theoretical plausibility: (i) study location: western versus non-western countries, (ii) gender: mixed versus mostly male (>75% male) versus mostly female (>75% female), (iii) mean age: <40 versus 40−48 versus >48 years (cut-offs were defined based on the number of studies within each age group), (iv) occupational class: mixed versus blue- versus pink- versus white-collar workers, (v) study design: longitudinal versus cross-sectional, (vi) assessment of sickness absence: self-reported absence versus company records, (vii) duration of sickness absence: undefined versus short-term (<4 consecutive weeks) versus long-term (≥4 consecutive weeks), and (viii) whether associations were adjusted for gender, age and socioeconomic position (not adjusted for all three confounders versus adjusted for all three confounders).

We composed a dataset including the effect estimates and the study characteristics. Univariate and multivariate meta-regression models were applied to determine the effect of the eight aforementioned study characteristics (independent variables) on the association between smoking and risk of sickness absence (dependent variable). Since a mean difference in sickness absence days per year could only be estimated for a limited number of studies, we did not conduct a meta-regression analysis for these studies.

Results

Study selection

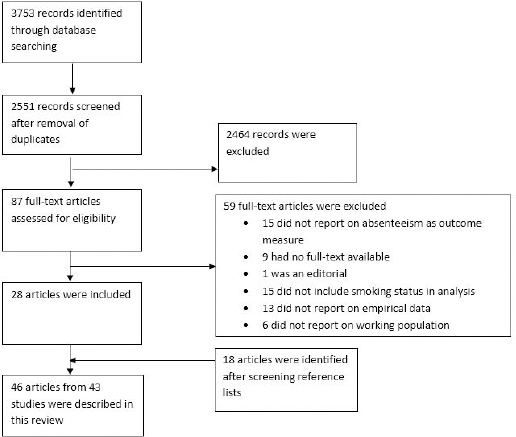

The study selection process is presented in figure 1. The literature search yielded a total of 3753 records. After removal of duplicates, 2551 unique records were screened on title and abstract. Subsequently, 87 articles were assessed for eligibility based on the fulltext, while including 28 articles (see figure 1). After screening reference lists of these studies and earlier systematic reviews, an additional 18 articles were included. In total, 46 articles reporting on 43 studies were included (61, 11, 18–62).

Study descriptives

The characteristics of the 43 included studies are summarized in table 1. In total, these studies included more than 1 354 126 participants (one study did not report numbers). The number of participants per study varied from 292 (33) up to 383 778 (55). The majority of studies reported on absence from workers in Western countries (N=39) (eg, Europe, USA, Australia, New-Zealand), while six studies were from a non-Western country, such as Uganda (26), Brazil (48), China (19), and Japan (21, 38, 44). Two studies reported on workers in both Western and non-Western countries (19, 44). About half of the studies had a longitudinal study design, varying in duration of follow-up from a few months (33) up to several years (44). Most studies reported on populations including both males and females, while some studies reported separate outcomes for both genders (31, 46, 47, 52, 58) or included only male employees (23, 44). Studies took place in a wide range of occupational settings, including a military base (26), schools (24), the construction industry (23), municipal government (18, 37, 44, 52) and an airline reservation office (33).

Table 1

Characteristics of included studies. For studies with insufficient information to estimate relative risk of absence or mean difference in days of sickness absence per year, corresponding cells were left blank. [CI=confidence interval; NA=not available; NL=The Netherlands; RR=risk ratio; SD=standard deviation.]

| Study | Location | Sample size | Longitudinal design/duration (months) | Adjusted a | Gender | Work sector | Assessment of absence | Definition of sickness absence | RR of absence (95% CI) | Mean diff. (SD pooled) (days absent per year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aaviksoo et al, 2013 (22) | Estonia | 2941 | No | No | Both | General | Self-reported | Any absence | 1.19 (0.91−1.57) | |

| Airaksinen et al, 2018 (18) | Finland | 65 775 | Yes/59 | Yes | Both | Government & healthcare | Records | Absence ≥90 days | 1.11 (1.06−1.16) | |

| Alavinia et al, 2009 (23) | NL | 5867 | Yes/15 | Yes | Male | Industry | Records | Any absence | 1.15 (1.06−1.24) | |

| Alker et al, 2015 (24) | USA | 630 | Yes/24 | Yes | Both | Education | Self-reported | Absence days | 1.43 (1.24−1.62) | |

| Asay et al, 2016 (25) | USA USA | 356 758 24 006 | No | No | Both | General | Self-reported | Absence days | 2.20 (1.45−2.95) 0.58 (0.24−0.92) | |

| Baker et al, 2017 (19) | USA EU China | 14 195 33 060 17 987 | No | No | Both | General | Self-reported | Absence % | 3.02 (1.67−4.37) 1.44 (0.11−2.77) 8.16 (6.21−10.11) | |

| Basaza et al, 2017 (26) | Uganda | 310 | No | No | Both | Military | Self-reported | Absence days | 8.40 (6.11−10.69) | |

| Bhojani et al, 2014 (27) | USA | NA | No | No | NA | General | Self-reported | Absence >5 days | ||

| Boles et al, 2004 (28) | USA | 2 264 | No | No | Both | General | Self-reported | Absence % | 0.94 (0.58−1.52) | |

| Bunn et al, 2006 (29) | USA | 34 934 | No | No | Both | General | Self-reported | Absence days | ||

| Bush & Wooden 1995 (30) | Australia | 21 984 | No | Yes | Both | General | Self-reported | Any absence | 0.51 (0.43−0.60) | |

| Christensen et al, 2007 (6, 31) | Denmark | 5020 | Yes/12-30 | Yes | Female Male | General | Records | Any absence ≥8 weeks | 1.65 (1.21−2.26) 1.30 (0.91−1.85) | |

| Gifford 2013 (32) | USA | 2917 | 24 | No | Both | General | Self-reported | Change in absence days | ||

| Halpern et al, 2001 (33) | USA | 292 | Yes/4-12 | No | Both | Office | Records | Absence days | 2.30 (0.49−4.11) | |

| Henke et al, 2010 (34) | USA | 11 217 | No | No | Both | General | Records | Workers compensation costs | ||

| Karlsson et al, 2010 (35) | Sweden | 341 | Yes/24 | No | Both | General | Self-reported | Any absence | 1.17 (0.76−1.79) | |

| Kirkham et al, 2015 (36) | USA | 17 089 | Yes/48 | Yes | Both | Industry | Self-reported | Absence days | 0.17 (0.08−0.26) | |

| Kivimäki et al, 1997 (37) | Finland | 763 | Yes/24 | No | Both | Government | Records | Any absence >3 days | 1.02 (0.86−1.20) | |

| Kondo et al, 2006 (38) | Japan | 529 | Yes/24 | Yes | Both | Industry | Self-reported | Any absence >5 days | 1.54 (0.71−3.33) | |

| Kowlessar et al, 2011 (39) | USA | 158 541 | No | Yes | Both | General | Self-reported | Any absence | 1.20 (1.18−1.23) | |

| Lucey 2008 (41) | UK | 400 | Yes/36-72 | No | Both | Healthcare | Records | Absence episodes | ||

| Lundborg 2007 (42) | Sweden | 10 561 | No | Yes | Both | General | Records | Absence days | 7.67 (5.43−9.91) | |

| Merrill et al, 2013 (43) | USA | 19 172 | No | Yes | Both | Healthcare | Self-reported | Any absence | 1.30 (1.18−1.43) | |

| Morikawa et al, 2004 (44) | Japan UK | 2504 (M) 6290 (M) | Yes/96-120 | No | Male | Industry Government | Records | Any absence >7 days | 1.43 (1.17−1.75) 1.51 (1.35−1.67) | |

| Musich et al, 2001 (45) | USA | 3338 | Yes/48 | No | Both | Industry | Self-reported | Workers compensation costs | ||

| Niedhammer et al, 1998 (46) | France | 3490 (F) 9065 (M) | Yes/12 | No | Female Male | Industry | Records | Any absence | 1.26 (1.11−1.43) 1.45 (1.16−1.80) | |

| Pai et al, 2009 (47) | USA | 3187 (F) 603 (M) | No | Yes | Female Male | Healthcare | Records | Any absence | 1.53 (1.07−2.19) 0.92 (.36−2.32) | |

| Rabacow et al, 2014 (48, 49) | Brazil | 2150 | Yes/12 | No | Both | Transport | Records | Any absence | 1.24 (1.00−1.55) | |

| Robroek et al, 2011 (50) | NL | 10 624 | No | No | Both | General | Self-reported | Any absence | 1.17 (1.06–1.29) | |

| Robroek et al, 2013 (51) | NL | 647 | Yes/12 | No | Both | General | Self-reported | Any absence | 1.38 (1.06–1.79) | |

| Roelen et al, 2018 (20) | Denmark | 2 492 | Yes/12 | No | Both | General | Records | Any absence >4 weeks | 1.95 (1.21–3.14) | |

| Roos et al, 2017 (40, 52) | Finland | 6 848 | Yes/60 | Yes | Female Male | Government | Both | Any absence | 1.28 (1.22–1.35) 1.36 (1.21–1.53) | |

| Serxner et al, 2001 (53) | USA | 35 451 | No | Yes | Both | General | Self-reported | Any absence ≥2 days | 1.19 (1.04–1.36) | |

| Sherman & Lynch 2013 (54) | USA | 14 387 | No | Yes | Both | General | Self-reported | Workers compensation costs | ||

| Sindelar et al, 2005 (55) | USA | 383 778 | No | No | Both | General | Self-reported | Any absence | 1.37 (1.14–1.65) | |

| Stewart et al, 2003 (56) | USA | 28 902 | No | Yes | Both | General | Self-reported | Any absence | ||

| Suwa et al, 2017 (21) | Japan | 18 683 | No | Yes | Both | General | Self-reported | Any absence | 1.15 (0.97–1.37) | |

| Torres Lana et al, 2005 (57) | Spain | 584 | No | No | Both | Healthcare | Records | Any absence | 1.51 (1.06–2.15) | |

| Tsai et al, 2003 (59) | USA | 2 203 | No | No | Both | Industry | Records | Absence rate per 100 persons ≥6 days | ||

| Tsai et al, 2005 (58) | USA | 2 550 | No | No | Female Male | Industry | Records | Absence ≥6 days | ||

| Tsai et al, 2011 (11) | USA | 6 551 | Yes/48 | Yes | Both | Industry | Records | Any absence ≥4 days | 1.21 (0.95–1.54) | |

| Wacker et al, 2013 (60) | Germany | 1 499 | No | No | Both | General | Self-reported | Any absence | 0.75 (0.56–1.00) | |

| Williden et al, 2012 (61) | New Zealand | 747 | No | No | Both | General | Self-reported | Absence hours | 20.96 (5.35–36.56) |

Sickness absence was assessed by self-report (25 studies), company record information (17 studies), or both self-report and company record information (1 study) and defined in several ways. The most frequently used measures were any absence (yes/no) and the total number of sickness absence days during a certain time period. Less frequently used were change in number of sickness absence days (32), sickness absence percentage (19, 28), workers’ compensation costs (34, 45, 54), number of sickness absence episodes (41, 59), and sickness absence hours (61).

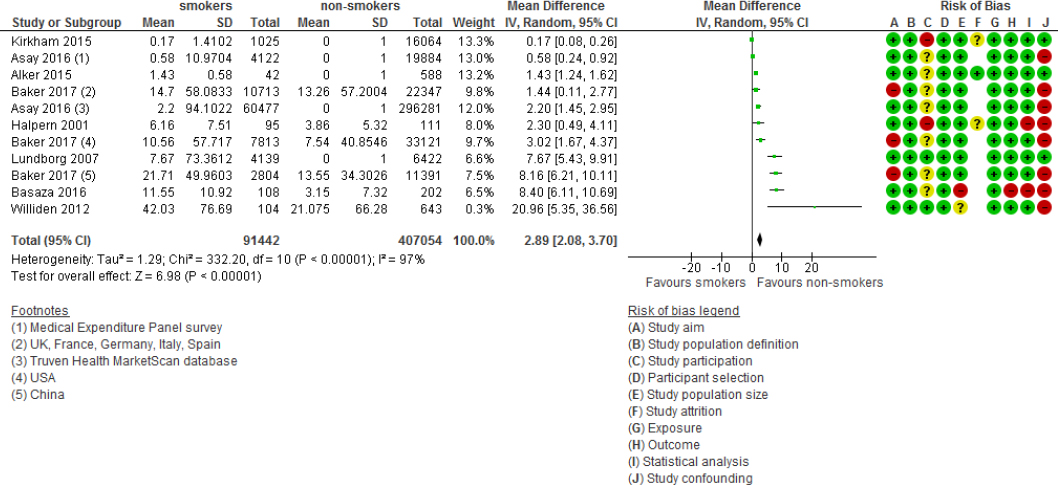

The risk of bias according to the ten methodological quality criteria is presented in figure 2. None of the articles scored low risk on all ten items. The majority of articles scored high risk of bias on the item regarding study confounding; they only reported univariate associations between smoking and sickness absence. Furthermore, the majority of studies scored high or uncertain risk of bias on the item of study participation, as they did not report sufficient information to gain insight into the participation rate of eligible persons.

Figure 2

Risk of bias of included studies. Risk of bias (ie, + = low risk of bias, - = high risk of bias and ? = unclear) is depicted in ten domains (ie, study aim, study sample definition, study participation, participant selection, sample size, study attrition, exposure, outcome, statistical analysis and study confounding). Cross-sectional studies are displayed with blank cells in the study attrition column.

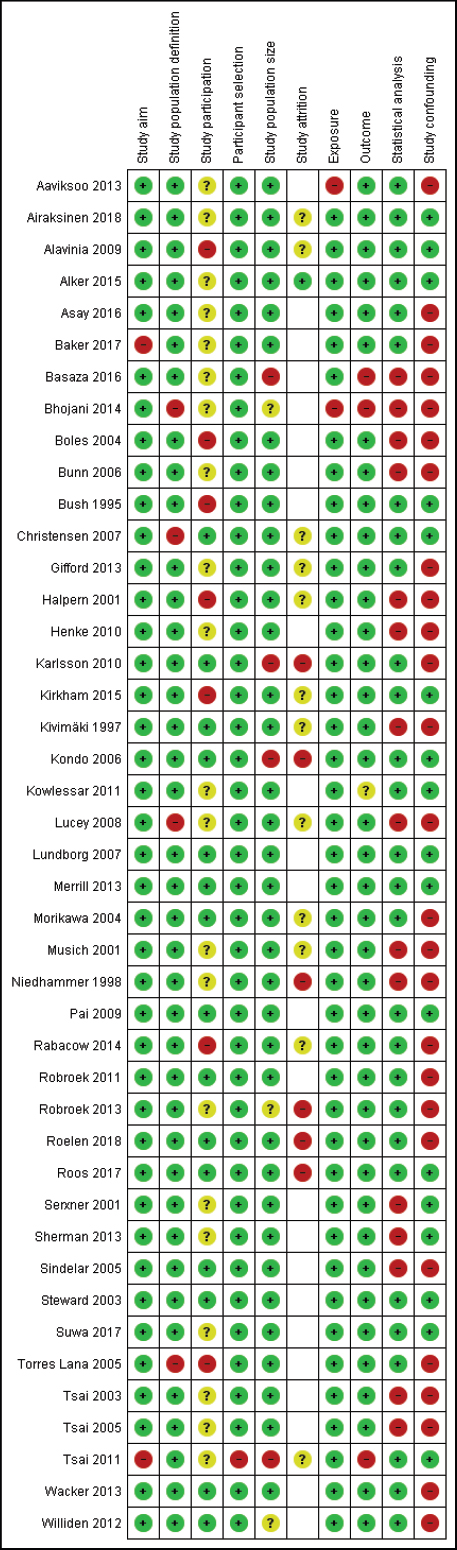

Risk of sickness absence

For 25 studies (with a total of 765 088 participants), reporting on a total of 30 associations, the outcome measures could be pooled into an estimate of relative risk of sickness absence (figure 3). These studies were used for the meta-regression analyses, assessing the associations between study characteristics, study design, and outcomes. Smoking was significantly associated with an increase in sickness absence, showing a total RR of 1.31 (95% CI 1.24–1.39) (table 2). Although not impacting on our conclusions, there are small differences in pooled effect size between table 2 and figure 3 due to differences in the estimation of the effect size. For the meta-analyses (figure 3), a random-effects model was applied, and for the meta-regression analyses (table 2), a fixed-effects model was used.

Figure 3

Study findings (ie, effect sizes and risk of bias) for articles reporting on the association of smoking and sickness absence. [SE=standard error; CI=confidence interval; IV=inverse variance.]

Table 2

Univariate and multivariate meta-regression models of dichotomous outcomes, with study location, gender, mean age, occupational class, study design, outcome assessment, outcome duration and correction for gender, age and socioeconomic status modelled as independent variables and effect size of the association of smoking on absence (expressed in beta) as dependent variable. [CI=confidence interval; RR=risk ratio; SE=standard error; SES=socioeconomic status.]

| Number of studies | Number of associations | Effect mean beta (SE) | RR (95% CI) | Between group difference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| Univariate beta (95% CI) | P-value | Multivariate a beta (95% CI) | P-value | |||||

| Total | 25 | 30 | 0.27 (0.03) | 1.31 (1.24–1.39) | ||||

| Study location | ||||||||

| Western | 21 | 26 | 0.27 (0.03) | 1.31 (1.24–1.39) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Non-western | 4 | 4 | 0.29 (0.07) | 1.34 (1.17–1.53) | 0.02 (-0.16–0.19) | 0.85 | -0.04 (-0.22–0.14) | 0.68 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Mostly male | 9 b | 10 | 0.30 (0.07) | 1.35 (1.18–1.55) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Mostly female | 5 b | 5 | 0.21 (0.04) | 1.23 (1.14–1.33) | 0.03 (-0.10–0.16) | 0.62 | 0.11 (-0.15–0.38) | 0.39 |

| Mixed | 15 | 15 | 0.27 (0.05) | 1.31 (1.19–1.44) | -0.06 (-0.23–0.10) | 0.46 | -0.01 (-0.28–0.27) | 0.96 |

| Mean age (years) | ||||||||

| <40 | 5 | 5 | 0.35 (0.10) | 1.42 (1.17–1.73) | Reference | Reference | ||

| 40-48 | 16 c | 18 | 0.25 (0.04) | 1.28 (1.19–1.39) | -0.10 (-0.26–0.06) | 0.20 | -0.09 (-0.26–0.08) | 0.32 |

| >48 | 4 c | 5 | 0.24 (0.03) | 1.27 (1.20–1.35) | -0.11 (-0.30–0.09) | 0.29 | -0.10 (-0.32–0.12) | 0.36 |

| Undefined | 1 | 2 | 0.38 (0.12) | 1.46 (1.16–1.85) | 0.03 (-0.23–0.29) | 0.81 | -0.11 (-0.47–0.26) | 0.56 |

| Occupational class | ||||||||

| Mixed | 16 | 18 | 0.29 (0.04) | 1.34 (1.24–1.45) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Blue collar | 3 d | 3 | 0.23 (0.07) | 1.26 (1.10–1.44) | -0.06 (-0.26–0.14) | 0.56 | -0.11 (-0.38–0.15) | 0.40 |

| Pink collar | 3 | 4 | 0.30 (0.08) | 1.35 (1.15–1.58) | 0.01 (-0.17–0.19) | 0.93 | 0.18 (-0.09–0.44) | 0.19 |

| White collar | 4 | 5 | 0.22 (0.07) | 1.25 (1.09–1.43) | -0.07 (-0.23–0.09) | 0.40 | -0.13 (-0.35–0.09) | 0.26 |

| Study design | ||||||||

| Cross-sectional | 12 | 13 | 0.25 (0.05) | 1.28 (1.16–1.42) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Longitudinal | 13 | 17 | 0.29 (0.04) | 1.34 (1.24–1.45) | 0.04 (-0.08–0.16) | 0.51 | 0.10 (-0.11–0.30) | 0.36 |

| Outcome assessment | ||||||||

| Self-reported sickness absence | 14 | 15 | 0.25 (0.04) | 1.28 (1.191.39) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Sickness absence records | 11 | 15 | 0.29 (0.05) | 1.34 (1.21–1.47) | 0.04 (-0.08–0.16) | 0.48 | -0.06 (-0.28–0.16) | 0.58 |

| Outcome duration | ||||||||

| Undefined | 21 | 24 | 0.25 (0.03) | 1.28 (1.21–1.36) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Short (<4 weeks) | 1 | 2 | 0.25 (0.17) | 1.22 (0.88–1.70) | 0.00 (-0.23–0.23) | 0.99 | -0.07 (-0.44–0.30) | 0.72 |

| Long (≥4 weeks) | 3 | 4 | 0.38 (0.13) | 1.46 (1.13–1.89) | 0.13 (-0.04–0.30) | 0.13 | 0.12 (-0.16–0.41) | 0.39 |

| Corrected for gender, age and SES | ||||||||

| No | 17 e | 19 | 0.28 (0.04) | 1.32 (1.22–1.43) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 9 e | 11 | 0.26 (0.04) | 1.30 (1.20–1.40) | -0.02 (-0.14–0.11) | 0.79 | -0.08 (-0.24–0.09) | 0.36 |

b Four studies reported on associations stratified by gender (31, 46, 47, 52). Therefore, the number of associations adds up to 29 instead of 25.

c One study (46) reported on two associations that are part of two different age categories. Therefore, the number of associations adds up to 26 instead of 25.

d One study (44) reported on two associations that are part of two different occupational classes Therefore, the number of associations adds up to 26 instead of 25.

e One study (31) reported on two associations, of which one is corrected for gender, age and SES and the other is not. Therefore, the number of associations adds up to 26 instead of 25.

We did not find statistically significant differences in association between smoking and sickness absence for study location, gender, age, occupational class, study design, type of assessment of sickness absence, short- versus long-term sickness absence, and adjustment for gender, age and socioeconomic position (table 2). However, we found potentially relevant differences in effect size for age and duration of sickness absence. For studies with a mean sample age <40, 40–48, and >48 years, we found a relative risk of sickness absence for smokers compared to non-smokers of 1.42 (95% CI 1.17–1.73), 1.28 (95% CI 1.19–1.39), and 1.27 (95% CI 1.20–1.35) respectively. For studies measuring short-term (<4 weeks) and long-term (≥4 weeks) sickness absence, the RR was 1.22 (95% CI 0.88–1.70) and 1.46 (95% CI 1.13–1.89), respectively. The stratified study findings are tabulated in supplementary figures S3-S10.

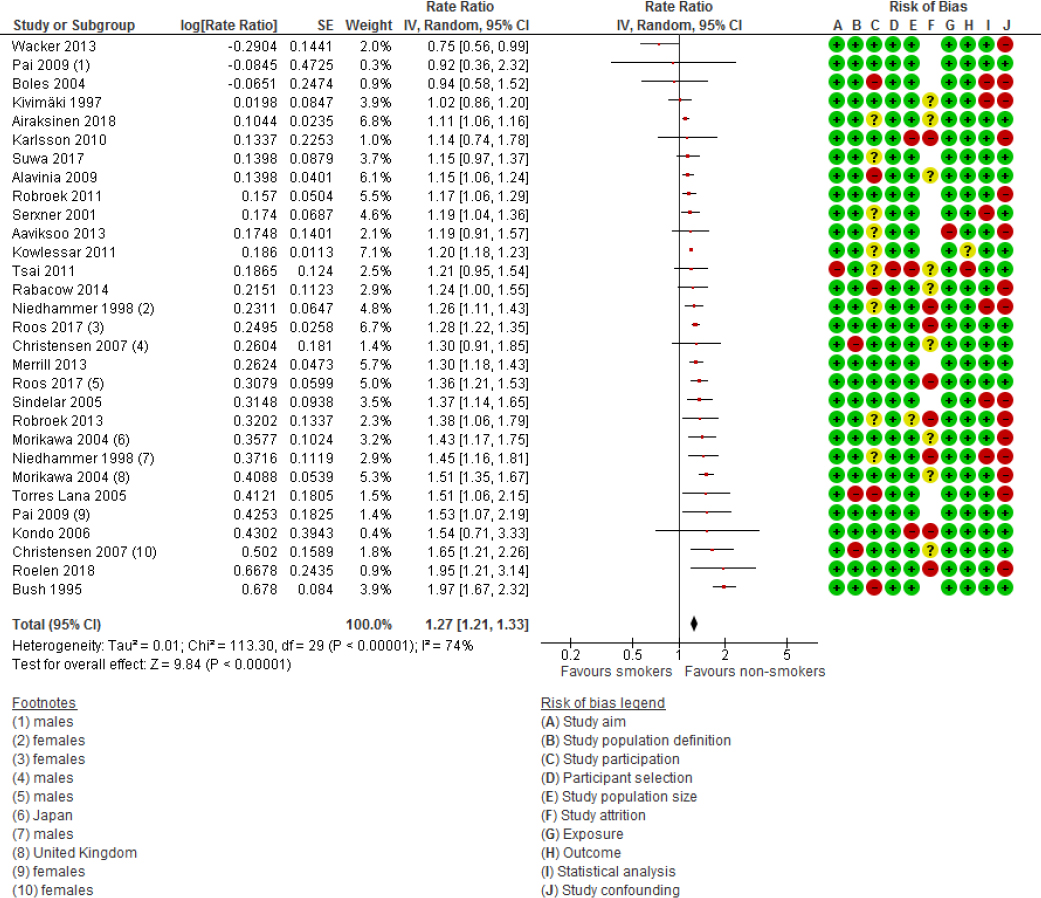

Sickness absence days

For eight studies (with a total of 475 635 participants) (19, 24–26, 33, 36, 42, 61), reporting on 11 associations in total, we were able to calculate a weighted mean difference in sickness absence days per year (table 1). The pooled weighted mean difference of sickness absence days per year for smokers compared to non-smokers was 2.89 days (95% CI 2.08–3.70) (figure 4).

Studies not included in pooled analyses

In total, ten studies were not included in the statistical pooling. For five studies (27, 29, 41, 56, 58), we did not have sufficient information to estimate either relative risk of sickness absence or number of sickness absence days. This was due to a lack of reporting of standard errors and CI of the outcome measure (27, 29, 41, 58) or no information on number or proportion of smokers in the research population (56). The corresponding authors of these studies were contacted but either did not respond or were unable to provide the required information. Other studies reported on different outcome measures, such as change in sickness absence over time (32), workers compensation costs (34, 45, 54), and sickness absence rate per 100 person years (59).

The studies not included in the statistical pooling all reported more absence for smokers compared to non-smokers, such as 34 more sickness absence days when comparing absences >5 consecutive days (27), 2.3 more sickness absence days per year (29), one less workday missed, two years after quitting smoking (32), 50% more sickness absence episodes (P<0.01) and 12.5 more sickness absence hours per 1000 working hours (P<0.05) (41). Furthermore, these studies reported higher total lost productivity time (2.85 for heavy smokers versus 1.45 for never smokers) (56), higher sickness absence frequency rates (smoking 33.0 versus non-smoking 22.4 (P<0.05) men; smoking 42.4 versus non-smoking 17.7 (P<0.05) women (58), and a higher sickness absence rate per 100 persons (smokers 20.9 versus non-smokers 12.2) (59). Additionally, studies reporting workers compensation costs found that these were higher for smokers compared to non-smokers (US$1010 for smokers versus US$767 for non-smokers (34); US$2189 for smokers versus US$176 for non-smokers (45); US$2697 for smokers versus US$2023 for non-smokers (54).

Additional analyses

As an additional analysis, we compared outcomes from studies that scored relatively low on risk of bias (low risk of bias on ≥8 items) with studies that scored relatively high on risk of bias (low risk of bias on ≤8 items). We did not find statistically significant differences in outcomes (RR 1.23, 95% CI 1.20–1.26 versus RR 1.21, 95% CI 1.18–1.23) between these two groups of studies (supplementary figure S11).

To determine whether the year of publication was of influence on study outcome, we conducted an additional meta-analysis to test for differences in risk of sickness absence for studies conducted before and after 2008. The studies published before 2008 generally scored higher on risk of sickness absence compared to studies published after 2008 (RR 1.38, 95% CI 1.23–1.53 versus RR 1.21, 95% CI 1.16–1.27, respectively) (supplementary figure S12). This suggests that the effect of smoking on sickness absence might decrease over time, which could indicate that the effect sizes reported in our study might have been larger if we would have included papers published longer than 25 years ago.

Discussion

Summary of findings

In this study, we aimed to review and summarize evidence on the association between smoking and sickness absence and determine whether there are differences in associations for studies with differences in study design, methodology and sample characteristics. Overall, we found evidence that smoking increased both the risk of sickness absence and the number of sickness absence days. Smoking was associated with a 31% higher risk of sickness absence compared to non-smoking and 2.89 more sickness absence days per year compared to non-smoking. We did not find statistically significant different effect sizes with varying study location, gender, age, occupational class, longitudinal versus cross-sectional design, assessment of sickness absence, duration of sickness absence, and whether outcomes were adjusted for gender, age, and socioeconomic status.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of our systematic review is that we were able to include a sufficient number of studies to perform a meta-regression analysis. In this way, we were able to take into account the influence of variations in sample characteristics such as study location, gender, age, and occupational class, which enables us to draw more generalizable conclusions. Another strength of the present systematic review is its generalizability to a general working population. By excluding studies that reported on specific sub-populations with disabilities or chronic diseases that are associated with more sickness absence, such as diabetes mellitus (7) or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (63), our study is of high relevance to employers aiming to improve workers’ health and increase the organizations’ productivity.

The present review has some limitations. First, some subgroups in the meta-regression analysis had only a small number of studies, as a result of which we might have been unable to detect important differences. For example, only a few studies had samples from non-western countries (19, 21, 26, 38, 44, 48), from a specific occupational class (11, 18, 23, 37, 44, 52) or consisted of mainly female participants (31, 37, 46, 47, 52). Furthermore, only a limited number of studies specified the duration of sickness absence, of which two associations (47) were classified as short-term absence and four associations (18, 20, 31) were classified as long-term absence.

Second, of the 46 articles we included, 18 articles we identified through screening references of included studies and previous reviews. A study from Greenhalgh and colleagues concluded that by relying solely on protocol-driven search strategies, important evidence might be missed and that “snowball” methods can identify high quality evidence that would not have been detected otherwise (64). A potential explanation for the high number of relevant studies identified through reference screening in the present review is that in studies researching the association between health and work productivity, smoking is often treated as a covariate and only reported in tables, figures or in the fulltext (but not in study title and abstract). By screening references of included studies and previous reviews, we were able to include several studies that we would otherwise have missed.

Third, we assumed that OR and HR could be interpreted as relative risks. However, OR can overstate the actual effect size when they are interpreted as relative risks (17). Since smoking increases sickness absence, the OR could be an overestimation of the RR. This may have caused some inaccuracy in the pooled estimation of the effect sizes (65). Furthermore, for five studies we assumed that the number of missed workdays for non-smokers was 0, with a standard deviation of 1, since only the excess number of missed workdays for smokers compared to non-smokers was reported, and not the actual number of missed workdays for smokers and non-smokers. We conducted sensitivity analyses with larger standard deviations but did not find large differences in the number of sickness absence days.

Fourth, smoking status was determined based on self-reports in all included studies and sickness absence was based on self-reports in about half of the included studies. Self-reported smoking status has been shown to be reliable (66, 67) and has shown to somewhat underestimate smoking status obtained by saliva or urine cotinine levels (68). A study comparing self-reported sickness absence days with employer registered sickness absence concluded that agreement between these two types of assessment of sickness absence is relatively good (69). In line with these findings, we did not find statistically significant differences in study outcomes for self-reported versus sickness absence versus objective assessment of sickness absence in our meta-regression analysis. Therefore, we expect the potential for bias due to self-reported sickness absence to be very small.

Interpretation of findings

Overall, we found evidence that smoking increased both the risk of sickness absence and the number of sickness absence days. Smoking can influence sickness absence through several pathways. First, smoking can lower an employee’s health status, due to, amongst other reasons, a decreased immune status, respiratory problems, cardiovascular problems, and cancer (2). Second, smokers might be more prone to accidents and injuries due to personality characteristics, smoking-associated disabilities, or being distracted while smoking a cigarette or while experiencing nicotine withdrawal (70, 71). Third, since smoking is associated with mental illness and substance abuse, the relation between smoking and sickness absence might partially be explained by mental illness and substance abuse as causes for absenteeism (72).

Our findings that smoking is associated with 31% higher risk of sickness absence and 2.89 more sickness absence days compared to non-smoking are consistent with a former systematic review on this topic by Weng and colleagues (5), who found a 33% higher risk of work absence and 2.74 more sickness absence days per year among smokers compared to non-smokers. We checked all the studies included in Weng et al’s review for eligibility but could only include 13 of the 29 studies in the present systematic review. Of the 16 studies not included 9 studies were excluded because they were not published in the past 25 years and 7 because they reported on specific subsamples of people with a disability that were not representative of the general working population. Therefore, the results of the present review are a more accurate reflection of the current working environment and the general employee population.

We did not find evidence that gender, age, study location and occupation class influenced the risk of smoking on sickness absence. This strengthens our conclusion and suggests that all employers and employees, irrespective of these characteristics, could equally benefit from smoking cessation, and therefore that all employee populations should equally be offered the opportunity to participate in smoking cessation interventions. However, for some covariates we found substantial differences in effect size, for example with regard to age and duration of sickness absence (73). This might indicate that some subgroups, such as younger workers (12), could benefit more from smoking cessation interventions and that potential effects might be more pronounced for longer periods of sickness absence. Therefore, more research should be conducted on the association between smoking and sickness absence in these sub-populations.

Several studies have estimated the costs of smoking at the workplace, based on empirical research of the association between smoking and work productivity (58, 74–79). These studies all conclude that smoking places a large economic burden on society. Halpern and colleagues found that for workers who quit smoking, productivity levels decreased in the first year compared to for those who continue smoking, but eventually exceeded productivity levels of continuous smokers in the following years (33). Potentially, productivity among former smokers can increase towards productivity levels of never smokers in the long term (80). Therefore, encouraging smoking cessation at the workplace could be highly cost-effective for employers and employees.

Multiple effective workplace-based smoking cessation interventions are already available, such as group behavior theory, individual counselling, NTR provision, and comprehensive programs (12). According to a qualitative evidence synthesis on employees views on workplace smoking cessation interventions, workplace smoking cessation inventions should have multiple components in order to facilitate employees in various phases of the cessation process, since needs and preferences can vary considerably between workers (81). A study simulating the effect of a worksite smoking cessation program found that potential savings from reduced sickness absence by far exceeded the program costs (80).

Concluding remarks

We found robust evidence that smoking increases both the risk and number of sickness absence days in the working population, regardless of differences in gender, age and occupational class. Encouraging smoking cessation at the workplace could be beneficial for employers and employees.