There are currently 140 million working days lost per year in the UK due to sickness absence, which equates to 2.2% of all working time or 4.9 days for each worker each year (1). Much sickness absence ends in a swift return to work however a significant number of absences last longer than they need to and each year >300 000 people fall out of work onto health-related state benefits (1, 2). Sickness absence has been found to be multi-causal, with the result that it is necessary to take into account both the working environment and the relationship between employee and their employer in addition to managing the particular disabling condition (3). Sickness absence remains a significant problem for employees, employers, and society.

Given the public health burden of sickness absence, it is surprising that relatively little is known on the optimal occupational health (OH) intervention strategies for employees at high risk of sickness absence (4). The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance on long-term sickness absence and incapacity considers early intervention, multidisciplinary approaches and interventions with a workplace component as important factors in the delivery of interventions to reduce long-term sickness absence (5). However, there is inconsistency in the definition of early intervention in different studies and some sickness absence interventions focus on those still in work and at risk of sickness absence (6–9). Recent systematic reviews found that multidisciplinary interventions involving consultation and consensus between all stakeholders (ie, the employee, health practitioners, and employer) to implement modifications for the absentee were consistently more effective than other interventions (6, 10). Palmer et al’s systematic review further showed effort-intensive interventions were less effective than simple ones and that future research on sickness absence management interventions should focus on the cost-effectiveness of simple, low-cost interventions (11).

Many studies have evaluated the effectiveness of return to work (RTW) interventions after injury and illness (12–21). These have ranged from minimal postal intervention, OH phone intervention to multidisciplinary approaches involving workplace assessment, work modifications and importantly case management involving all stakeholders (22–25). However, to our knowledge there are far fewer studies or reviews of very early intervention under two weeks (26, 27), despite the fact that there are a number of commercially successful companies offering sickness absence management services to employers, which involve the employee being telephoned on day one (28, 29).

National Health Service (NHS) sickness absence rates tend to be higher than other sectors and rates within the NHS vary significantly by region and type of NHS body and also by job and grade (30–32). The Scottish Government set a challenging Health Improvement, Efficiency, Access, Treatment (HEAT) target of 4% sickness absence for NHS Scotland to be achieved by 31 March 2009 (33). In 2007 NHS Lanarkshire (NHSL, 11 000 people) had one of the highest levels of sickness absence (peaking at 7.35%) of all the mainland health boards in Scotland, despite applying all NHS policies directed at supporting sick employees and reducing sickness levels as measured by absence from work. These policies included: an attendance management policy (referral to occupational health services, OHS, for absences >28 days); training managers in RTW interviewing; provision of parental and special leave; open access to counselling and staff physiotherapy; and participation in the healthy working lives award scheme. In response to this HEAT target and cabinet minister criticism, NHSL and Salus (NHSL’s provider of OH, safety and RTW services) facilitated an innovative approach to sickness absence management and introduced the EASY service (Early Access to Support for You) in May 2008 with all staff included by March 2009. Demou et al (34) have described the rationale and implementation of the EASY service in NHSL. In brief, this new telephone-based sickness absence management service provides early intervention based on the biopsychosocial model (35) applying cognitive behavioral principles, and utilizing evidence-based interventions (16, 22–24, 36). A brief description of the process follows.

After the employee notifies his manager of his absence, the manager contacts the EASY service. The absent staff member is telephoned on the first day of absence by an EASY administrator team member, selected for his good interpersonal communication skills and non-judgmental friendly support, who follows an algorithm of offering assistance. The employee is asked about the health problem causing the sickness absence episode and his views about returning to work. He is also informed about the following services to which he can self-refer if appropriate: (eg, OH, physiotherapy, counselling services); family-friendly leave entitlements; infection control, and cold/flu advice. After the call, the EASY call handler notifies the manager, usually by email, that contact has been made with the employee, and shares the support offered and estimated RTW day if known. If the employee is still absent on day 3, he receives a further EASY service call. If still off work at day 10, the employee is referred to an OH service (previously day 28) where, if necessary and dependent on need, a case manager who can offer non-clinical support is assigned.

We have undertaken a detailed evaluation of the EASY service from May 2008 to May 2012. This paper compares sickness absence rates in both the NHSL and NHS in the rest of Scotland and describes sickness absence trends in NHSL after implementation of the EASY service. The aim of this study was to answer the followings specific research questions: (i) Is the EASY service effective in reducing sickness absence? (ii) Does the EASY service offer net economic benefits?

Methods

The study analyzed two sources of sickness absence data: NHS Scotland Information Services Division (ISD) sickness absence data and sickness absence data collected directly by the EASY service in NHSL.

ISD sickness absence data

Sickness absence data was requested from NHS Scotland ISD. We were provided with monthly sickness absence rates (defined as the total number of working hours lost due to sickness absence divided by the total number of possible working hours) for all health boards in Scotland. This allowed us to produce two series of data for NHSL and NHS Scotland excluding NHSL (NHS rest of Scotland) from January 2007 to August 2012. Data prior to 2007 was not available. In 2007, there were 11 185 staff employed in NHSL and 143 032 staff employed in the NHS rest of Scotland.

The two series of data were analyzed using Box-Jenkins Autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) time series methodology. For the NHSL time series, we adopted an input series that would allow the EASY intervention to slowly evolve from the start of the intervention in May 2008, when <0.01% of NHSL staff were covered, to when all NHSL staff were included (March 2009). Specifically, the intervention was modelled as “0” up to May 2008 and thereafter as a cumulative intervention, until March 2009 when the series was coded as “1”. In order to put the EASY intervention in context, the NHS rest of Scotland series had to be modelled too as there was effectively a parallel (but less intensive) intervention at the national level to drive down absence rates. The other health boards were using different models/policies to that of the EASY intervention. The national intervention, for the purposes of statistical modelling, took the form of 0 up to May 2008 and 1 thereafter.

The 4% sickness absence HEAT target to be achieved by 31 March 2009 was further taken into account in the model as it was announced to all health boards in December 2007 (33). For NHSL, this involved designing and implementing the EASY service in late 2007/early 2008, while other health boards, although not introducing an EASY type service, were tightening their sickness absence policies and procedures in the same time period. Specifically in this model, the HEAT target announcement was modelled as 0 up to December 2007 and 1 thereafter.

The EASY service database

Salus at NHSL routinely collects all sickness absence events reported to the EASY service. The anonymized EASY database includes all sickness absence events from late May 2008 to early May 2012. Key descriptive statistics were carried out on the EASY database.

For the purposes of the analyses, there were three main exclusions criteria: (i) If the first day of absence (FDA) was a Saturday or Sunday (N=3012) [the EASY service is a Monday–Friday service and therefore it’s not possible for these absentees to be phoned by the EASY service on the first day of absence]; (ii) date opened (ie, the date the EASY service contacted the absentee) was before the first day of absence (N=711); and (iii) date opened was equal to or after the RTW date (N=2916).

Due to overlaps between the three exclusion criteria, 5707 absences were excluded resulting in 32 921 absences (32 359 closed, 562 open) being analyzed.

For the mean duration of absence analysis, the data was divided into four years as follows: (i) year 1, May 2008–April 2009; (ii) year 2, May 2009–April 2010, (iii) year 3, May 2010–April 2011, (iv) year 4, May 2011–April 2012.

The novelty of the EASY service is that the intervention begins on the day one of sickness absence. The service relies on the line manager to inform the EASY call center of the employee’s absence and, although the aim is for all absentees to be phoned on the FDA, this is not always the case. Reporting compliance is defined as the percentage of sickness events reported to EASY on the FDA.

Survival analyses and Cox’s proportional hazards model

Absence duration was analyzed using Kaplan Meier survival analyses and Cox’s proportional hazards model with Stata version 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) to determine the hazard (risk) of the absentees returning to work. The censor date was 2 May 2012. The model takes into account each sickness absence event but also the multiple absences by individuals by calculating cluster robust standard errors. The following variables were included in the controlled model: sex, age, job family, cause of absence, day of absence, month of absence, year of absence. In the reporting compliance analysis, those absentees who returned to work on day one or two were removed in order to make the three groups (those phoned on the same day as FDA, those phoned one day after FDA, and those phoned two days after FDA) comparable.

Economic evaluation of the EASY service

The economic benefit from the EASY intervention was calculated by valuing the marginal gain in sickness absences. The gain was calculated as the additional mean hours per month of reduced sickness absence in NHSL relative to the hours of sickness absence reduced in other NHS boards. Hourly gains per month were converted to an annual equivalent and valued at the mean annual salary per staff member in NHSL. This gain was assumed to represent the value to NHSL of the additional hours gained. Mean annual salary was used in this study because, although job family was known, the individual job level was not recoded. Total EASY set-up and operating costs were subtracted from this estimated saving to provide the estimated net economic benefit from operating the EASY service.

Research and Development (R&D) management approval was granted to conduct the study within NHSL (R&D ID Number L11071).

Results

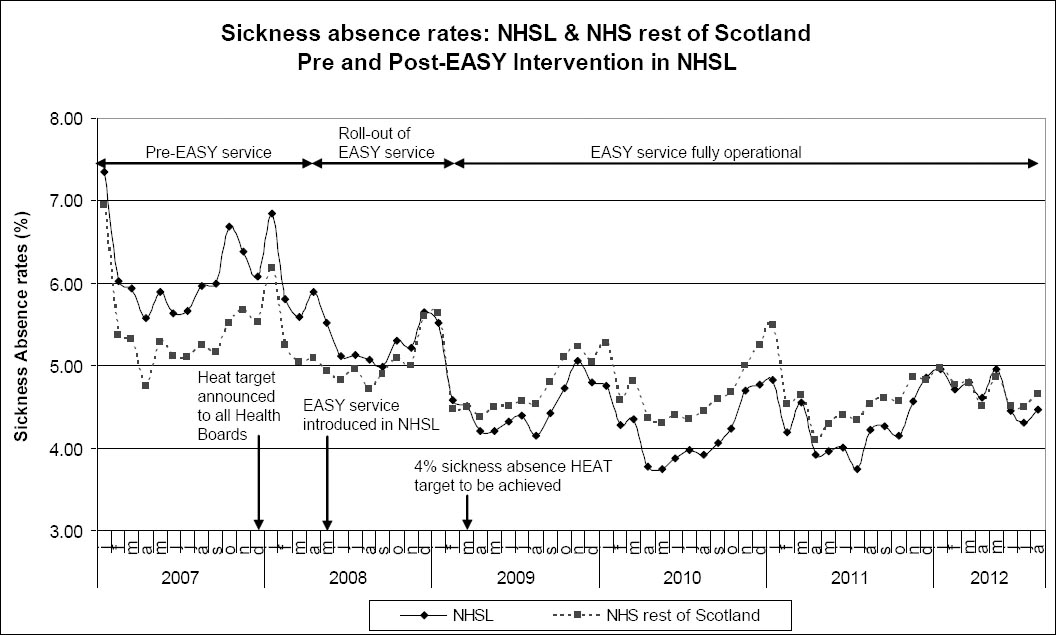

Figure 1 shows the monthly sickness absence rate for NHSL (solid line) and NHS rest of Scotland (dashed line) from January 2007 to August 2012.

Figure 1

Monthly sickness absence rate for National Health Service Lanarkshire (NHSL) (solid line) and for NHS rest of Scotland (dashed line) from January 2007 to August 2012. [EASY=Early Access to Support for You; HEAT=Health Improvement, Efficiency, Access, Treatment]

For both NHSL and NHS rest of Scotland, there is clear evidence of a downward trend in sickness absence rates that is non-linear, as well as subject to strong seasonality (figure 1). The first 15 data points are prior to the implementation of the EASY intervention in NHSL, and NHSL has a higher sickness absence rate than that of the rest of Scotland for this time period. There was a continuing downward trend in the monthly sickness absence rate for NHSL and NHS rest of Scotland, but, for the first time in January 2009, NHSL had a lower sickness absence rate then NHS rest of Scotland. From April 2009, the NHSL monthly sickness absence rate was consistently lower than NHS rest of Scotland, apart from a brief period between March–May 2012.

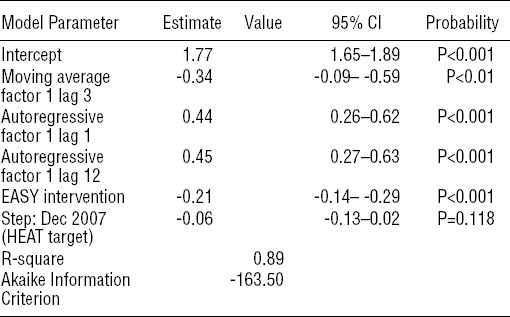

The best model for NHSL was an autoregressive (AR) (1, 12) moving average (MA) (3) model with hyperbolic trend (not shown) to capture the gradual non-linear decline in the absence rate. The model coefficients are shown in table 1a. All parameters are highly significant and the adjusted R2 shows that the model is a good fit to the observed series. Adding the intervention effect to the model improved the fit significantly. The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) statistic is much lower and the adjusted R2 increased to 0.89. The coefficient on the EASY intervention variable shows that the impact of the intervention was to reduce the sickness absence rate in NHSL by approximately 21% [95% confidence interval (95% CI) 14–29) P<0.001]. In addition, the variable capturing the HEAT announcement shows that the effect was to reduce sickness absence by 6%, but this did not reach statistical significance.

Table 1a

Final model NHSL (National Health Service Lanarkshire) time series models. [95% CI=95% confidence interval; EASY=Early Access to Support for You; HEAT=Health Improvement, Efficiency, Access, Treatment]

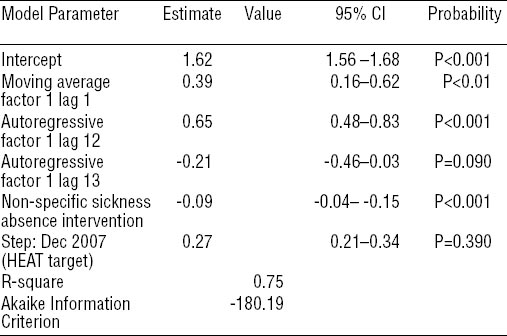

For NHS rest of Scotland (table 1b), the final model was identified as AR (1, 12, 13). After introduction of the policy intervention, the model fit was significantly better with the AIC statistic lower at -180.2 and adjusted R2 =0.75. The coefficient on the non-specific intervention variable shows that the tightening of the sickness absence policies across health boards (excluding NHSL) reduced sickness absence rates by approximately 9% (95% CI 4–15) with this significant at P<0.001. The effect of the HEAT announcement was found to be a 2.7% increase in sickness absence but this did not approach statistical significance.

Table 1b

Final model NHS (National Health Service) rest of Scotland time series models. [95% CI=95% confidence interval; HEAT=Health Improvement, Efficiency, Access, Treatment]

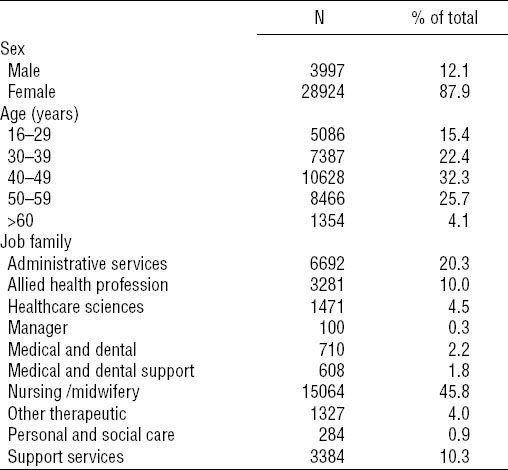

As shown in table 2, the majority of the EASY service participants were female, 62% were >40 years, and 45% were nurses/midwives.

Table 2

Description of EASY (Early Access to Support for You) service population by sex, age and job family, 2008.

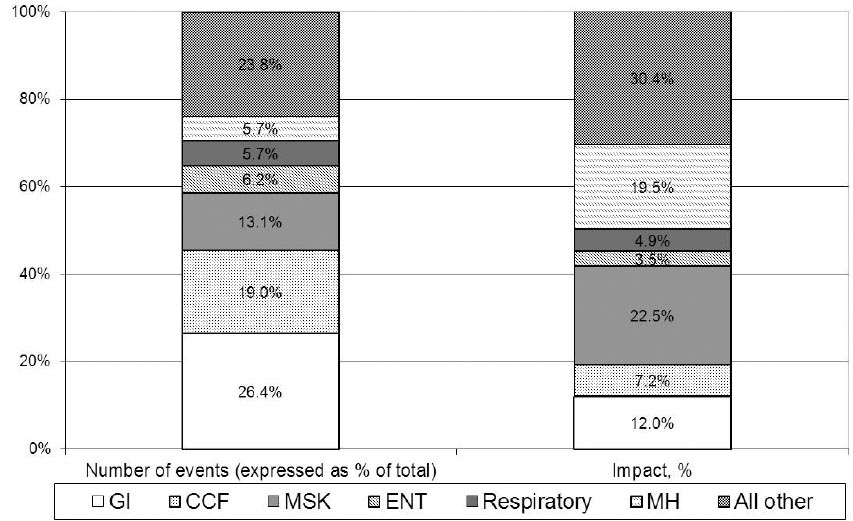

The EASY database records up to 25 reasons for absence. Figure 2a shows the top 6 causes of sickness absence plus all other causes. The left hand column shows the number of sickness absence events expressed as a percent of the total. The main cause of sickness absence is gastrointestinal problems (GI, 26.4%), followed by cold, cough and flu (CCF, 19.0%) and then musculoskeletal problems (MSK, 13.1%). The right hand column shows the impact of the sickness condition. GI problems only account for 12.0% of total days absent whereas MSK problems and mental health (MH) problems account for 22.5% and 19.5% of days absent due to these latter conditions typically having longer durations of absence.

Figure 2a

Cause of sickness absence (Number and impact). [GI=gastrointestinal problem; CCF=cold, cough & flu; MSK=musculoskeletal problem; ENT=ear, nose & throat; MH=mental health problem.]

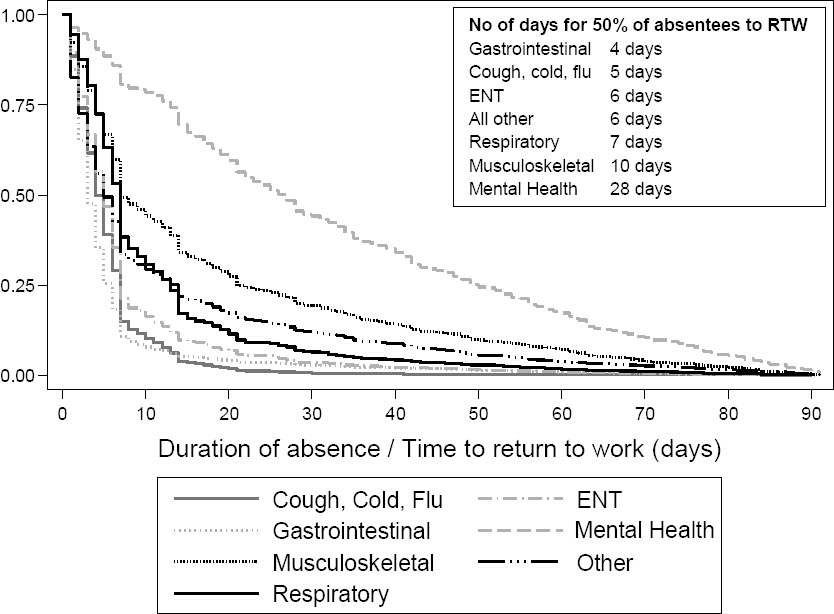

Figure 2b shows a Kaplan Meier RTW curve for all events by cause of sickness absence. RTW for staff absence because of MH problems is much longer than all other causes of absences. For example, 50% for staff absent from work due to a MH problem had returned to work by 28 days whereas 50% of staff off work due to respiratory problems returned to work within 7 days.

Figure 2b

Kaplan Meier return to work (RTW) curve for all events by cause of sickness absence. [ENT=ear, nose & throat.]

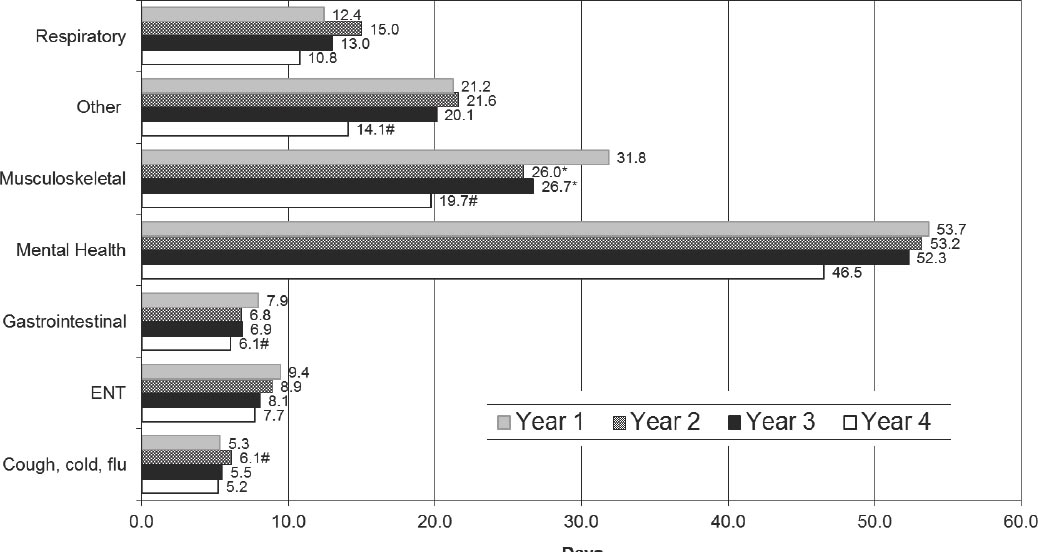

Figure 3 shows the mean duration of absence by each absence cause for years one, two, three, and four of the EASY service. Absences due to MSK problems lasted an average 31.8 days in year one, and there were significant decreases in mean duration of MSK absences in years two (26.0 days) and three (26.7 days). MSK absences decreased further in year four (mean duration 19.7 days, a 38% decrease compared to year one). There was no significant change in the mean duration of all other absences except for the following: CCF absences increased in year two compared to one by 15.1%; GI absences decreased by 22.8% in year four compared to one; “other” causes which decreased by 33.5% in year four compared to one. MH absences showed a decreasing trend in the length of absence, but this effect was not significant.

Figure 3

Mean duration (in days) of absence by cause of sickness absence for years 1–4 of the EASY (Early Access to Support for You) service. *P<0.05; #P<0.01. [ENT=ear, nose & throat]

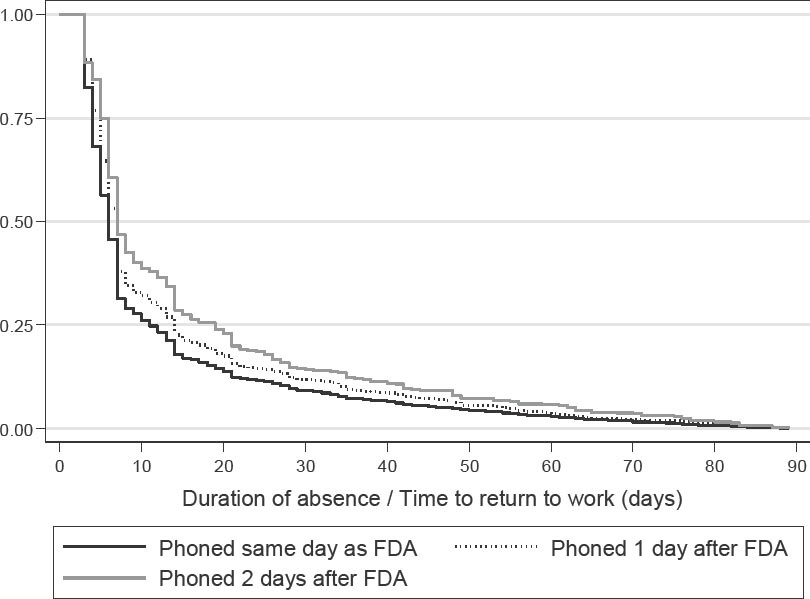

Reporting compliance is defined as the percentage of sickness events reported to the EASY service on the FDA and, in this study, was calculated to be approximately 80%. Figure 4 compares the RTW patterns of those who were phoned by the EASY service on the same day as their FDA (N=18 573) with those phoned one day after FDA (N=3096) and those phoned two days after FDA (N=855). All the mild cases of employees who returned to work on day one or two (N=8003) were removed prior to analyses in order to make the three groups comparable. The likelihood of returning to work using Kaplan Meier survival analyses and Cox’s proportional hazards model was estimated. Uncontrolled, those phoned one day after FDA were 13.8% less likely to return to work, P<0.001 (controlled 1.1% less likely to return to work, P=0.592). Uncontrolled, those phoned two days after FDA were 28.3% less likely to return to work, P<0.001 (controlled 13.7% less likely to return to work, P<0.001).

Figure 4

Kaplan Meier return to work (RTW) curve for those phoned by the EASY (Early Access to Support for You) service on the same day as first day of absence (FDA), 1 day and 2 days after FDA.

Extrapolating the time series analyses for NHSL and NHS rest of Scotland indicated the EASY service had achieved additional savings, relative to other initiatives conducted across Scotland, of 1825 hours per month. Over the four years up to May 2012, these totaled 87 600 hours or 2336 additional weeks or 44.71 years saved as a result of the EASY service.

The NHSL annual report and accounts for the period 1 April 2008 to 31 March 2012 reported total salaries and total staff employed. Over the four years, the mean annual salary per staff member was £31 240 (37). Multiplying annual years saved (44.71) by this annual salary provides an estimate of total savings from reduced sickness absence of £1 396 680.

Data provided by NHSL human resources showed overtime costs reduced from £3.43M in 2008/09 to £2.46M in 2009/10 to £1.85M in 2010/11, with a slight increase to £2.30M in 2011/12. Some of the savings in hours and hence costs may be because of the EASY service but attribution is not possible. There was no evidence of a reduction in other labor related costs such as bank nursing and midwifery costs in NHSL relative to the rest of Scotland.

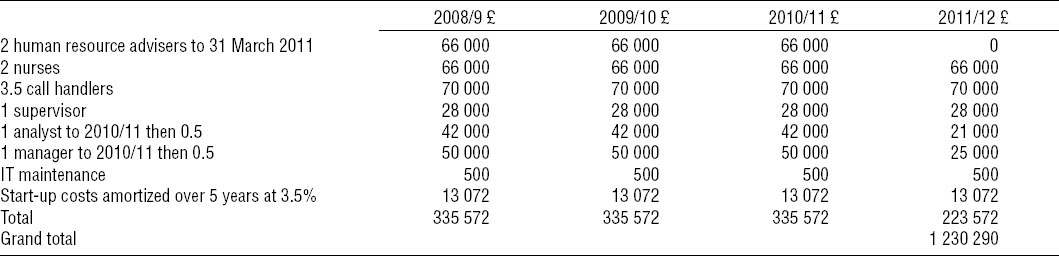

Salus provided estimates of the annual staff required, associated operating costs, and initial start-up costs for the EASY service (table 3). In the first three years, 10.5 staff were employed in operating the EASY service, declining to 7.5 in 2011/12. Start-up costs incurred in 2008/09 consisted of £23 000 for capital equipment, 50% of the annual cost of a band-8 nurse and 10% of the cost of the Director of Salus. These costs were amortized over five years at an annual cost of capital of 3.5%. Estimated total costs over the four years are £1 230 290.

The estimated net benefit of £166 390 is obtained by deducting this cost from the estimated savings. Return on investment is the ratio of savings to direct cost and was estimated to be 1.135 to 1. In future years, if savings remain at 1825 hours per month, the annual value of these is estimated at £349 170, compared to costs of £223 572 (costs from 2011/12), giving a return on investment of 1.56 to 1.

Discussion

This study has shown that the EASY service was effective in reducing sickness absence by 21% in NHSL, whereas the nonspecific tightening of the sickness absence policies across the rest of Scottish NHS health boards reduced sickness absence by approximately 9%. This new approach to managing sickness absence enabled NHSL to decrease its sickness absence rate from above the Scottish average (NHS rest of Scotland) to below the average and even below the 4% HEAT target in the summer months. Furthermore, the EASY service reduced the mean duration of MSK absences in years two, three, and four compared to year one and the findings from this study suggest that intervention on day one is better than day two, and day two is better than day three, although residual confounding by other factors affecting outcome cannot be ruled out. This study also showed that the EASY service improved economic efficiency; the value of the hours saved comfortably exceeded the cost of the intervention.

The EASY service is based on the biopsychosocial model (35) and uses a case management approach to manage sickness absence. Case management uses a demedicalized model and is defined as a collaborative process which assesses, plans, implements, coordinates, monitors and evaluates the options and services required to meet an individual’s health, social care, educational and employment needs, using communication and available resources to promote quality cost effective outcomes (38) and is about empowering individuals. Smedley et al (39) showed that a later (from four weeks) sickness absence intervention for NHS staff in England, which used an intensive case management-based rehabilitation program modelled on that in NHSL, reduced long-term absence in hospital employees. The main improvement in outcomes was for absences attributed to health problems other than musculoskeletal disorders and mental illness. This provides evidence of the utility of the biopsychosocial model both for long- and short-term absence.

The EASY service intervened from day one of sickness absence. NICE guidance on sickness absence management recommends early sickness intervention but there are few studies or reviews (26, 27) of very early intervention (under two weeks) despite a number of commercially successful companies offering sickness absence management services to employers which involve the employee being telephoned on day one (28, 29). One very early intervention that decreased sickness absence significantly after implementation was a petrochemical company in-house disability management program, DMP (26, 29). The DMP intervenes very early in the sickness absence spell and at day four of absence, the absentee is assigned a case manager. As with the EASY service, the case manager communicates with and coordinates efforts of the parties involved (the employee, employee’s physician, company physicians, employee’s supervisor, human resources, benefits administration) to ensure that the employee receives proper medical care, access to professional healthcare advice and company benefits for which they are eligible, and explores the appropriateness of transitional duty. The goal of the DMP is to enhance the ability of an employee experiencing a non-occupational illness or injury to safely return to transitional or full duty at the earliest possible time. Like the EASY service, the DMP showed that a successful intervention required sustained efforts of the employee, employer, OHS and HR and that, by connecting all the stakeholders, the employee can successfully return to work.

This study showed that the EASY service was effective in reducing sickness absence, in terms of hours lost, in NHSL. From April 2009, the NHSL monthly sickness absence rate was consistently lower than NHS rest of Scotland apart from a brief period between March to May 2012. Reasons for this are unclear but may reflect a reduction in management focus, which occurred because of the lower sickness absence levels. A limitation was that monthly sickness absence data was only available from January 2007 and therefore only 15 time points were available from before the start of the intervention. While this is a low number of pre-intervention data points, the series shows no sign of any obvious trend over that period that could “confound” the effect of the EASY intervention when it started.

Much sickness absence data, including the ISD data used in this study, does not record the reason for absence. However the EASY database collected locally by Salus in NHSL does record cause of sickness absence and therefore a major advantage for this study was being able to investigate duration of sickness absence spell by cause of absence and show differential effects. With the exception of the category CCF, all other categories of sickness absence showed a reduction in duration over the four years and this was significant for MSK, GI, and “other” (figure 3). This suggests that the intervention was influencing sickness absence behavior among employees and may also reflect the more proactive approach that the service required of line managers. It could be argued that the intervention would be better focused on MSK, MH, and other causes of long-term absence, and other usually shorter-term conditions including CCF could be managed by line managers. However the EASY intervention was designed to be a supportive, non-judgmental biopsychosocial intervention for all staff with health problems, and such health interventions were viewed as being outside the remit and competencies of line managers.

It was not possible to have a control group in NHSL as the EASY intervention was unique to NHSL. However, during the roll out period it was observed that staff not involved in the early roll out of the intervention also demonstrated a significant reduction in sickness absence (table 1a), possibly a result of the extensive communication exercise to all staff.

The novelty of the EASY service is that it intervenes on the FDA. The service relies on the line manager informing the EASY call center of the employee’s absence and although the aim is for all absentees to be phoned on the FDA, compliance with this guidance was calculated to be approximately 80%. Those absentees phoned on the FDA and those phoned on subsequent days are not directly comparable because every day of delay in not being phoned by the EASY service removes the mild cases who have already gone back to work. We therefore attempted to correct for these cases by carrying out the analysis shown in figure 4 and removing the early returners to work, although residual confounding cannot be ruled out. It is also possible that the characteristics of line managers and their employees phoned subsequent to FDA differed from those involved in FDA calls. Those absentees who were phoned one or two days after their FDA were significantly less likely to return to work than those phoned on their FDA. This finding shows the importance of early intervention for all absentees and might support earlier intervention in routine, general NHS non-occupational service delivery for individuals with MSK, GI, and possibly other disorders.

In 2009, the Department of Health commissioned an independent review of the health and wellbeing of NHS staff in England (30). The Boorman review found that the direct cost of staff sickness absence was £1.7 billion and recommended that the NHS could reduce rates of sickness absence by a third with an estimated annual direct cost saving of £555 million. Other previous research has shown that workplace-based interventions, including disability management interventions, often do not undertake economic analyses and that those that do are often weak (40, 41). Therefore it was important that an economic evaluation of the EASY service was included as part of this study. Reducing absences may be anticipated to bring about other savings, particularly for critical frontline services; sickness absence disrupts handovers on a ward and places strain on remaining staff. A key limitation is not being able to quantify these benefits. Thus estimated benefits are conservative.

A second limitation is the analysis assumed the EASY service only saved additional hours in NHSL over and above those achieved by other health boards in Scotland. In fact, the EASY service also made a major contribution to the Board achieving the national rate reduction. For example, if 50% of the costs delivered the reduction in sickness absence equivalent to that achieved nationally, then the additional costs would fall to £615 145, yielding net savings of £781 535, with a return on investment of 2.27 to 1.

The data show the EASY service contributing to both efficiency savings, equivalent to 44 years of absences avoided, and direct savings through reductions in absences and overtime costs. However, the savings represent the opportunity cost of the absence and are not net cash savings. Moreover the hours saved have been valued at the average mean salary cost, which may overstate savings if the majority of the hours saved are paid below the mean salary rate. This is a data limitation. There is also a risk that the costs to deliver the service are not fully captured or are overstated given this was a new service with increased start-up expenditure which has not been sustained. Although the EASY service has reduced sickness absence overall, further study is needed to ascertain the relative effectiveness in subgroups of absence and whether there is an optimum time to intervene on the different conditions causing sickness absence.

A further potential benefit of reduced sickness absence is that it is an indirect measure of staff engagement and, where staff engagement has been showed to be high, it has been observed that patient mortality is reduced (42). This was not further explored in this study but is worthy of further research.

The aim of this project was to evaluate an early intervention and inform potential wider public health interventions. After the project was agreed, a major government-funded sickness absence review was published in 2011 (1) and this was followed by a government response in early 2013 proposing a health and work service (HWS) to be introduced in late 2014 which will provide an independent OH assessment and intervention in workers who have had sickness absence for four weeks (2).

This study provides important new evidence for policy-makers to consider. The established paradigm within the Department for Work and Pensions and many enterprises is that early intervention is not an efficient use of resources because of the large number of individuals who will return to work relatively early without any specific intervention. This reactive rather than proactive paradigm has informed the timing of the proposed HWS at four weeks (2); the design of the job retention and rehabilitation pilots which tested interventions over six weeks off work (43); eligibility for the work program being set at between 6–12 months off work (44); many individuals with long-term work incapacity not accessing vocational rehabilitation interventions for several years after losing their jobs; and the traditional approach by employers of arranging an OH intervention after day 28 (45). What is clear from this study and the lessons drawn from sports medicine (46) is that very early intervention can be beneficial. Indeed, it may help to prevent chronicity of health problems and the downward spiral to worklessness and dependency among the significant proportion who fall out of work due to ill health each year and who cumulatively contribute to the £100 billion ill health and benefit costs that the UK spends each year (1, 2).

The finding that a service of this type can reduce sickness absence among these employees is likely to be generalizable to other similar populations and should be trialed in other settings. If this effect was consistent then it would be evidence pointing to the need for a much more proactive, very early, biopsychosocial approach for the management of sickness absence in the wider community. Given sickness absence costs to the economy around £15 billion a year (1), if the 21% reduction in sickness absence that was achieved by this model was extrapolated across the UK, this would reduce societal costs by potentially £3.15 billion pounds. Sickness absence is important for individuals, enterprises, and socioeconomic wellbeing and further exploration of early sickness absence interventions are required.

Concluding remarks

This project has shown that the EASY service, which intervenes from day one of sickness absence, has been effective in reducing sickness absence in NHSL compared to all other health boards in Scotland and has enabled NHSL to perform better than all other Scottish health boards in terms of sickness absence management and potentially improving patient care. In particular the EASY service is effective in reducing sickness absence in terms of hours lost in NHSL. The mean duration of MSK absences was significantly shorter in years two, three, and four compared to year one. Those absentees phoned on FDA were more likely to return to work than those phoned on subsequent days. The EASY service has realized economic benefits; the value of the hours saved from the reduced sickness absence exceeds the cost of operating the service. The study highlights the importance of early intervention for sickness absence management. Further studies could be undertaken to identify if more or less contact with the absentee is beneficial and whether the timing of that contact is important for particular absence subgroups.