To mitigate the potentially negative economic effects of an aging population, policy-makers are looking for ways to maximize the labor market participation of older workers (1, 2). Managing chronic physical conditions is one possible target, since these conditions both interfere with labor market participation (3–6) and increase in prevalence with age (7). Addressing mood disorders is another area of interest, as these disorders also negatively affect labor market participation (4, 8–17) and, although their prevalence does not increase with age (18), it does increase in the presence of chronic physical conditions (19, 20).

Focusing on individuals with a chronic physical condition concurrent with a mood disorder may prove particularly fruitful, as these conditions may act synergistically, producing more disability than expected given the effects observed for each condition alone (21). This synergism is thought to arise via biological, behavioral, cognitive, and social pathways (22). From a biological perspective, for example, several chronic physical conditions and mood disorders are associated with the same types of physiological disturbances leading to overproduction of stress-related hormones; prolonged exposure to these hormones can lead to the onset of new, and/or progression of existing, illnesses (23, 24). From a behavioral perspective, treatment adherence may be one pathway through which physical and mental co-morbidities interact, as there is evidence to suggest that depressed individuals are less likely to adhere to chronic physical condition treatment regimes than their non-depressed counterparts (25–28). Perception of pain may offer a cognitive pathway for interaction, as cognitive distortions inherent in depression have been shown to lead depressed individuals to take greater notice of negative stimuli than non-depressed individuals (29). As a result, depressed individuals appear to perceive more pain than their non-depressed peers (30). Finally, lack of social support may be one social pathway through which synergism arises (22). While social support can buffer against the negative outcomes of illness, depressive symptoms can impair social relationships (22, 31).

The results of studies focused on the impact of chronic physical conditions concurrent with a mood disorder on disability have been mixed, with some studies reporting no interaction (32, 33), others noting a synergistic interaction (21, 34, 35), and still others alluding to an interaction without explicating the details or providing any formal statistical test (36–45). Adding to the confusion in this literature, one study reported a negative interaction, wherein the impact of the concurrently observed mental and physical conditions produced less disability than expected, given the effects of each condition alone (46).

Confusion in this literature is likely due to variation in: (i) the approaches used to assess interaction; (ii) the definitions of mental and physical health conditions; and (iii) the measures of disability. First, as reviewed above, a number of pathways suggest that mood disorders can interact synergistically with chronic physical conditions, meaning the conditions produce more disability when they co-occur than expected given the effects of each condition alone. Statistical additive interaction tests are the only way to test for this synergistic possibility (47). Yet, some of the previous studies have only conducted statistical multiplicative interaction tests (by including an interaction term in a nonlinear regression model, such as a logistic model), while other studies have failed to include any statistical interaction test. In the latter cases, the authors have simply noted that the effect observed for the concurrent conditions is greater than the effect observed for either condition alone.

Second, in many studies, mood disorders have been grouped with anxiety and substance abuse conditions. However, given their different presentations and prognoses, it is reasonable to expect different labor market outcomes for each specific group of mental disorders (when observed alone or concurrent with a chronic physical condition). Similarly, while some studies have focused on specific chronic physical conditions (such as diabetes), many studies have collapsed a number of physical conditions together into a single group. A small group of studies have conducted a separate interaction analysis for each specific physical condition, and revealed important differences in the interaction across conditions (34, 35, 48).

Finally, most studies in this area have used general measures of disability that simultaneously consider functioning at work, home, and in other realms of life. While some authors have argued that these general measures of disability provide a good proxy for days of absenteeism (35, 37), they are not well-suited for tapping into presenteeism. While the exact definition of presenteeism is evolving, some authors have referred to this construct as “at-work productivity loss” or “at-work disability”, and described it as the “phenomena of loss of work productivity in terms of quantity or quality of work done due to illness or injury in people who are present at their job” (p23,49). It is important to consider presenteeism specifically as many chronic conditions (mental and physical) have been shown to have a larger impact on this more subtle form of disability than on absenteeism (3).

In this paper, we explore the impact of mood disorders and five age-related chronic physical conditions (arthritis, back pain, diabetes, heart disease, and hypertension) on presenteeism. We also examine how mood disorders interact with each physical condition to affect this work outcome.

Methods

Sample

This study used cross-sectional secondary data from the 2003, 2005, 2007, 2009, and 2010 cycles of the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS). Each CCHS uses a multi-staged, stratified sampling frame to target individuals aged ≥12 years, living in private dwellings in Canada. People living on Indian reserves or Crown lands, residents of institutions, full-time members of the Canadian Armed Forces, and residents of certain remote regions are excluded from the sampling frame. The household response rates for 2003, 2005, 2007, 2009, and 2010 cycles of the CCHS were 87.1%, 84.9%, 84.6%, 80.8%, and 80.7% percent, respectively; with corresponding selected-person response rates being 92.6%, 92.9%, 91.7%, 92.1%, and 88.6% (50–54). For the purpose of this paper, we restricted our sample to those respondents who were employed. We also restricted the sample to those 25–74 years of age, as respondents >74 years were not asked questions about labor market participation, and respondents <25 years often combine labor market participation with study or are not in the labor market. These inclusion criteria created a sample of 132 072 eligible respondents. However, only 120 005 respondents were included in the analysis, as 11 247 (8.5%) were excluded due to incomplete data. Complete cases did not differ from incomplete cases with respect to the activity restrictions at work or the presence of any of the chronic conditions of interest in this analysis. Approval for the secondary data analyses was obtained through the University of Toronto, Health Sciences I Ethics Committee.

Outcome – presenteeism.

CCHS respondents were asked “Does a long-term physical condition or mental condition or health problem, reduce the amount or the kind of activity you can do at work?”. Three response categories were available, including: “never”, “sometimes” and “often”. Consistent with previous research that has used data arising from this question to examine presenteeism (55, 56), we created a binary variable wherein respondents who answered “sometimes” or “often” were collapsed into one group and compared to those who answered “never”. Respondents are not offered a time frame of reference for answering this question.

Exposures – mood disorders and age-related chronic physical conditions.

CCHS respondents were asked about the presence of specific mental and physical disorders. The interviewer prefaced this question with “Now I’d like to ask about certain chronic health conditions which you may have. We are interested in long-term conditions which are expected to last or have already lasted 6 months or more and that have been diagnosed by a health professional.” Each condition was asked about explicitly (as opposed to relying on respondents to recall all applicable disorders without prompt). We created six binary variables for the purposes of this analysis, one for each of the following conditions: (i) arthritis or rheumatism (excluding fibromyalgia), (ii) back problems (excluding fibromyalgia or arthritis), (iii) diabetes, (iv) heart disease (including congestive heart failure), (v) hypertension and (vi) mood disorders (such as depression, bipolar disorder, mania or dysthymia). We chose the five chronic physical conditions because they are prevalent and show a positive relationship with age.

Covariates

We created control variables to represent survey year (a nominal categorical variable with five groups), age (treated continuously in regression analyses, though a four-group categorical variable was used to describe the sample in Table 1), gender, household composition (a nominal categorical variable with four groups), highest level of education completed (a nominal categorical variable with four groups), occupational physical demands (imputed based on occupational code, using the Human and Resources Skills Development Canada classifications (57) and included as a nominal categorical variable with four groups), work hours (a nominal categorical variable with four groups), province/territory of residence (a nominal categorical variable with eleven groups), and urban versus rural location of residence. We also created a binary variable to indicate the presence of migraines and another to indicate the presence of anxiety disorders (which were assessed using the same method described above for the mood disorders and age-related chronic conditions).

Statistical analyses

In our first set of analyses, we explored the distribution of presenteeism across each of our study variables. To do so, we examined the percentage of respondents reporting presenteeism in each subgroup of each study variable, and then we estimated unadjusted and fully adjusted prevalence ratios (PR) using a modified Poisson regression with robust error variance estimation methods to compare the risk of presenteeism across subgroups of each study variable.

In our second set of analyses, we explored presenteeism within groups defined by the co-occurrence of mood disorders and each of the five chronic physical conditions. To do so, we examined the percentage of respondents reporting presenteeism across each co-occurrence group and then generated unadjusted and fully adjusted PR using modified Poisson regression models. More specifically, we estimated five separate sets of models (one unadjusted and one fully adjusted) for each co-occurrence pair. In these models, we created dummy variables to represent the four possible combinations of disease states: (i) neither a mood disorder nor the specific chronic physical condition of interest in the model, (ii) a mood disorder without the specific chronic physical condition, (iii) the specific chronic physical condition without a mood disorder, and (iv) both a mood disorder and the specific chronic physical condition. The latter three dummy variables were then entered simultaneously into the regression models. We then used the PR for these dummy variables to calculate synergy indices (SI). Estimates of the SI and associated 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated using methods outlined by Hosmer and Lemeshow (58) and expanded upon by Andersson and colleagues (47). When an SI and its corresponding lower CI are >1, the interpretation is that the co-occurrence of the two conditions in question has a synergistic effect. In other words, in our analysis, if the SI and corresponding upper CI are >1, we have evidence to suggest that a mood disorder concurrent with a (specific) chronic physical condition increases the likelihood of presenteeism more than would be predicted by the sum of the individual main effects. On the other hand, when an SI and its corresponding upper CI are <1, the interpretation is that the co-occurrence of the two conditions in question has a negative interaction. In our analysis, this type of result would mean that a mood disorder concurrent with a (specific) chronic physical condition is associated with a lower burden of presenteeism than would be predicted by the sum of the individual main effects.

In each of the analyses described above, we explored whether the effects differed for men and women. However, as the results did not differ by sex, we present the pooled results below. We examined variance inflation factors (VIF) in the fully adjusted models to identify instances of multicollinearity amongst the independent variables. The maximum VIF we observed was 1.6, which is well below 10, the rule of thumb value used to flag instances of potential concern (59).

We used SAS version 9.3 to conduct all analyses (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). All analyses were weighted to account for the probability of selection into the original sample and non-response. However, we did not adjust the standard errors for the complex sample design because the bootstrapping macros available from the data custodian (Statistics Canada) did not cover the procedure we used for our analysis; as a result, the standard errors reported below may be underestimated.

Results

Table 1 describes how presenteeism was distributed in our sample. In addition, this table presents the unadjusted and fully adjusted prevalence ratios (PR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) of reporting presenteeism associated with each study variable. While each of the six conditions are associated with an increased likelihood of reporting presenteeism, back pain shows the strongest relationship [prevalence ratio (PR) 2.70, 95% CI 2.57–2.83] and hypertension shows the weakest (PR=1.18, 1.11–1.25).

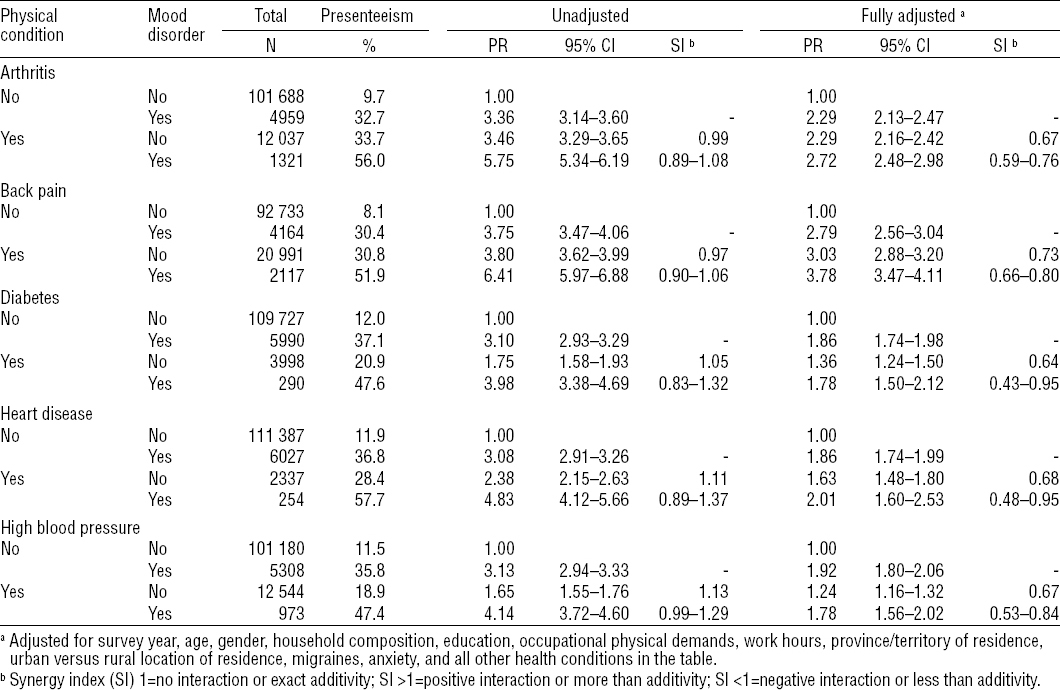

Table 2 shows how presenteeism was distributed within groups defined by the co-occurrence of a mood disorder and each of the five chronic physical conditions. Respondents with neither the mood disorder nor the chronic physical condition in question were the least likely to report presenteeism. Meanwhile, those with both a mood disorder and the chronic physical condition in question were the most likely to report presenteeism. Table 2 also includes the unadjusted and adjusted PR (and 95% CI) of reporting presenteeism associated with having a mood disorder concurrent with each of the five chronic physical conditions, as well as the SI estimates for each mood/physical co-occurrence. All unadjusted SI estimates are around one, indicating that there was no interaction between mood disorders and any of the specific physical conditions examined. Meanwhile, all adjusted SI estimates were <1, suggesting that having a mood disorder concurrent with a physical condition is associated with a lower burden of presenteeism than the sum of the effects for each condition alone. This negative interaction was statistically significant for each disease combination examined.

Table 2

Respondents experiencing presenteeism across different mood and physical condition combinations, Canadian Community Health Survey, 2003–2010. Including employed respondents 25–74 years (N=120 005). [PR=prevalence ratio; 95% CI= 95% confidence interval.]

Post-hoc analyses

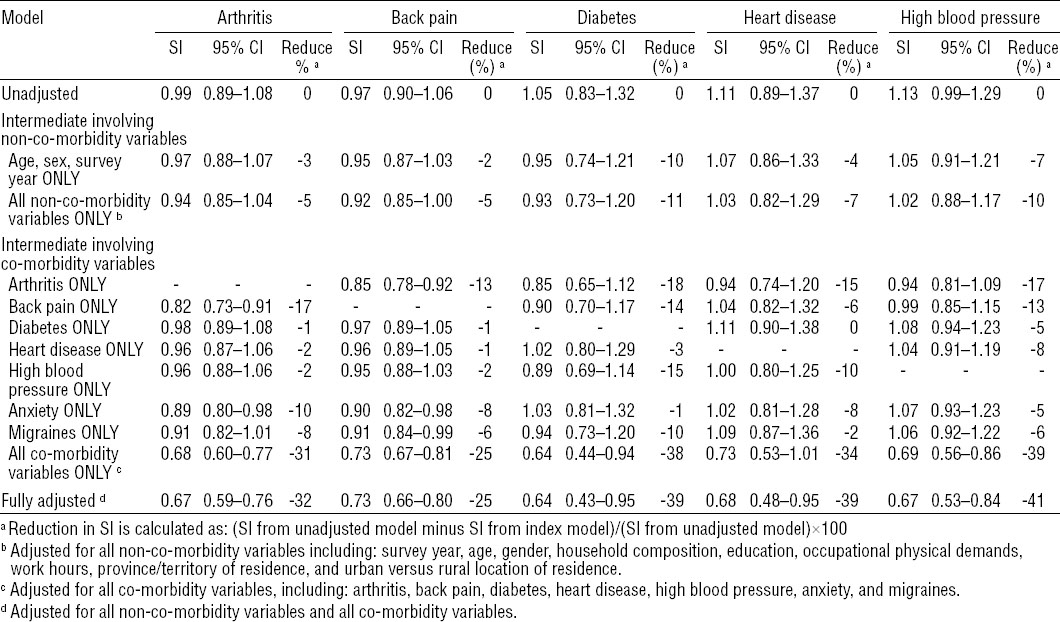

We conducted a set of post-hoc analyses to better understand the negative interactions, which were not anticipated. More specifically, we estimated intermediate modified Poisson regression models to explore which covariates were causing the SI estimates to move away from the null. Through these analyses, we determined that controlling for the non-co-morbidity variables (primarily sociodemographic and work-related variables, but also survey year) had relatively little impact on the SI estimates (reducing these estimates, relative to the unadjusted, between 5–11%), while controlling for co-morbid health conditions had a more substantial impact on the SI estimates (reducing the estimates, relative to the unadjusted, by between 25–39%). Though most health conditions contributed to the reduction in the SI, arthritis and back pain appeared to have the largest effects, with adjustment for arthritis causing a reduction in the SI (relative to the unadjusted) of between 13–18%, and adjustment for back pain causing a reduction of between 6–17%. We present the SI estimates corresponding to each intermediate regression model, along with the percentage change in SI estimates (relative to the unadjusted), in table 3.

Table 3

Synergy index (SI) for activity restrictions at work (presenteeism) for combinations of mood disorders and specific physical conditions. Canadian Community Health Survey, 2003–2010. Including employed respondents 25–74 years (N=120 005).

The PR estimates (and corresponding 95% CI) from the intermediate models (from table 3) are reported in the Appendix (www.sjweh.fi/data_repository.php). By comparing the attenuation in the PR (unadjusted versus adjusted) across the concurrent subgroups (mood only, physical only, or concurrent), we can see that the attenuation was greatest in the PR for the concurrent subgroup. For example, while adjustment for all co-morbid conditions reduced the PR of the mood-disorder-only and arthritis-only groups by 30%, this adjustment reduced the PR for the concurrent (mood with arthritis) group by 50%.

Discussion

Consistent with previous research, the findings presented in this paper show that mood disorders and five age-related chronic conditions are associated with presenteeism. Unlike most previous studies, however, we found that, when looking at adjusted estimates, a mood disorder concurrent with a chronic physical condition was associated with a lower burden of presenteeism than the sum of the effects for each condition alone. This effect was not hypothesized and is unexpected. This effect was also in contradiction with the unadjusted findings, wherein there was no interaction between mood and any of the physical conditions. Only one previous study in this area reported a similar negative interaction effect of concurrent mental and physical conditions (46). However, it is difficult to compare our findings to this study’s because the authors did not provide details about this finding. Instead, Merikangas and colleagues (46) simply noted that they: (i) examined all possible two-way interactions for 15 physical and 15 mental conditions, (ii) found 25% of the interactions to be significant, and (iii) found the “vast majority” of the statistically significant interactions “were negative, indicating that the effects of the comorbid conditions are less than the sum of the effects of the two conditions alone” (p1182, 46). It is also difficult to compare our findings to this previous study because, while Merikangas and colleagues focused on the number of days that respondents were unable to work (in the previous 30 days), we used a self-reported measure of restrictions at work.

A series of post-hoc analyses revealed that the negative interactions were primarily a result of adjusting for other co-morbid health conditions. More specifically, we found that such adjustment greatly attenuated the estimated PR for those with a mood disorder concurrent with a physical disorder. This attenuation, in turn, produced an SI estimate <1, indicating a negative interaction between the mood disorder and index physical condition. This attenuation reflects an instance of confounding, whereby those with a mood disorder concurrent with a single chronic physical condition are more likely to both have at least one other chronic health condition and experience presenteeism. For example, 82% of respondents with both arthritis and a mood disorder had at least one additional chronic health condition; meanwhile only 64% of respondents with arthritis (but no mood disorder) had at least one other condition, 63% of respondents with a mood disorder (but no arthritis) had at least one other condition, and 34% of respondents with neither arthritis nor a mood disorder had at least one other condition. This pattern of co-morbidity was consistent across all physical condition/mood disorder combinations (wherein those with both index conditions were more likely to have at least one non-index condition than those with only one or neither index condition). This patterning highlights the analytic challenge of estimating the impact of pairs of co-morbid conditions on labor market activities: while other co-morbid conditions are reasonably conceived of as confounders in this relationship, caution must be taken when interpreting estimates of this relationship that have been adjusted for non-index conditions that are strongly associated with both the co-occurrence of the index conditions and the labor market activity under study.

Our findings suggest, if one aims to reduce the prevalence of presenteeism, there is likely no added benefit (beyond that conferred by managing the separate conditions) to focusing on individuals with a chronic physical condition concurrent with a mood disorder, as their combined effects are not greater than their additive effects. We note, however, that our findings should not be extended to either absenteeism or labor market exit, which are different outcomes from the one used in the current analyses. Ideally, we would also have examined labor market exit as a concurrent outcome, but it was not available in the data sources used for this paper.

The current study has added value to this body of literature by: using the appropriate statistical test for examining synergistic interactions; focusing on mood disorders specifically (rather than grouping multiple mental disorders together); examining the interaction separately for five age-related chronic physical conditions; and exploring the impact of the interaction on a measure of presenteeism (rather than absenteeism). The data used in this study also afforded us the opportunity to explore this issue in a large general population-based sample of respondents.

Despite its size and representativeness, the data we used was cross-sectional and, therefore, prevents us from drawing any causal conclusions about the relationships investigated. This missing information on temporality is compounded by the fact that the question concerning activity limitations at work does not offer respondents a time frame of reference; as a result, it is impossible to know (even theoretically) whether the activity restrictions began before or after the chronic conditions or mood disorders (which the survey defines for respondents as conditions that “are expected to last or have already lasted 6 months”). A second limitation of our study concerns the cognitive burden posed by our measure of presenteeism. As noted above, respondents were asked “Does a long-term physical condition or mental condition or health problem, reduce the amount or the kind of activity you can do at work?” While this question allows us to tap in to a form of presenteeism, which may be more affected by a number of chronic conditions than absenteeism (3), it is a cognitively burdensome question. Respondents must keep multiple thoughts in mind simultaneously, including: (i) all of their long-term physical and mental conditions, (ii) all of the symptoms arising directly from the conditions and/or indirectly via the medications used to treat the conditions, and (iii) all of the activities of their job that may be impacted by the symptoms. Given the complexity of this task, it is possible that the activity restrictions reported in our data are inaccurate. In addition, it is unclear how respondents would incorporate complete absences from work when answering this question; some respondents may only consider time physically present at work when answering, while others may also reflect upon periods of absenteeism. More methodologically sound measures of presenteeism are available (49), but unfortunately none have been used in the national general population-based surveys conducted in Canada. Nevertheless, this crude measure of presenteeism produced results consistent with previous research, with each health condition (alone) showing a negative impact on work.

A third limitation of our study is the way mood disorders were defined. By honing in on mood disorders specifically, we were able to provide more refined estimates of the interaction than previous studies that collapsed mood disorders with anxiety and substance use conditions. However, our measure would have been even cleaner had we been able to tease apart unipolar and bipolar depression, as the effects of these conditions on labor market outcomes may be different (60). Furthermore, all chronic conditions examined in this analysis were based on self-report, and therefore potentially inaccurate. Finally, diagnosis by a medical professional was required for all chronic conditions; as a result, the impact (and/or interaction) of undiagnosed conditions cannot be surmised from our results.

Concluding remarks

Given the goal of reducing presenteeism, our findings suggest that targeting those with chronic physical conditions (particularly, those with back pain or arthritis) or mood disorders may be a productive use of resources. The combined effect on presenteeism when the two types of conditions occur simultaneously is similar to the additive effect of these conditions when each occurs in isolation. However, given the broader goal of maximizing labor market participation, honing in on individuals with concurrent disorders may be fruitful, as those with concurrent disorders may be at greatest risk for absenteeism or labor market exit (either temporarily during bouts of unemployment or permanently via premature retirement). Future research is required to generate more specific policy and practice implications.

Future studies should explore the relationships between these conditions (alone and in combination) and labor market outcomes (presenteeism, absenteeism and labor market exit) using longitudinal data (wherein the timing of conditions and labor market outcomes can be established). When presenteeism is the focus, a more robust measure should be employed. Assuming similar results arise from longitudinal data, studies should then shift focus to understanding how these conditions reduce productivity and/or cause labor market exits. This understanding will be critical in developing effective interventions aimed at maximizing the labor market participation of workers suffering from mental and physical chronic conditions.