Sickness absence is clearly multifactorial, but exposures at the workplace are certainly an important part of health and illness among adults and correspondingly related to absence rates in contemporary work-life. To develop, improve and implement effective sick-leave prevention measures, we need to understand the risk factors. Previous research on the work environment and sickness absence has mainly focused on physical working conditions (1, 2) and psychosocial factors such as job demands and control (3–5). Less is known about how and when workplace bullying is related to sickness absence, beyond cross-sectional studies demonstrating associations between the two. However, both primary studies (6, 7) and meta-analyses (8, 9) suggest exposure to bullying at the workplace increases the risk for mental and somatic health complaints prospectively. As an extension of these findings, it seems plausible that bullying should also be a risk factor for sickness absence. To contribute to the understanding of bullying and sickness absence, we first present a theoretical model to illustrate how bullying may be related to absence. Thereafter, we provide a systematic review and meta-analysis of existing peer-reviewed empirical studies on the relationship between bullying and absence. Finally, using our theoretical model as an outset, we discuss whether the existing knowledge base is adequate with regard to the development and implementation of well-informed interventions and preventive measures. The quality of evidence for an association between bullying and sickness absence will be evaluated on the basis of the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) guidelines (10).

Workplace bullying refers to situations at the workplace where an employee repeatedly and over a prolonged time period is exposed to harassing behavior from one or more colleagues (including subordinates and leaders) and where the targeted person is unable to defend him-/herself against this systematic mistreatment (11). Consequently, workplace bullying is not about single episodes of conflict or harassment at the workplace, but rather a form of persistent abuse where the exposed employee actually is (or perceives him/herself to be) submissive to the perpetrator (12). Bullying is also not about negative actions and interpersonal conflicts that inevitably occur at workplaces and that are within the framework of the work contract or a legal and regulated framework.

Prevalence estimates suggest that about 15% of employees at a global basis perceive themselves as victims of workplace bullying at any given time (13). Employees exposed to bullying report more health complaints compared to non-bullied colleagues. In the early stages of a bullying process, targets commonly experience reactions such as worrying, distress, despair, and confusion (14). Psychological and psychosomatic reactions become more prominent and severe with persistent exposure. Illustrating these reactions, research shows that prolonged bullying is associated with subsequent reports of anxiety (8, 15), depression (8, 16), suicidal ideation (17, 18), headache (19), and sleep problems (20–22). In a meta-analysis it was found that exposure to bullying predicted subsequent mental health complaints [odds ratio (OR) 1.68, 95% confidence interval (95% CI) 1.35–2.09] and somatic complaints (OR 1.77, 95% CI 1.41–2.22) after adjusting for baseline health status (9). These same health complaints found among employees exposed to bullying are also commonly reported symptoms among sickness absentees (23). These associations with later health problems suggest that bullying could be an important risk factor and prominent precursor for sickness absence. In support of this assumption, a meta-analysis (15) found that exposure to workplace bullying was related to subsequent absence with an OR of 1.67 (95% CI 1.35–2.07). However, as this meta-analysis only included a limited number of studies without addressing the nature of the association, the existing synthesized evidence is restricted. In addition, there is a lack of theoretical models to explain when and how bullying is related to sickness absence.

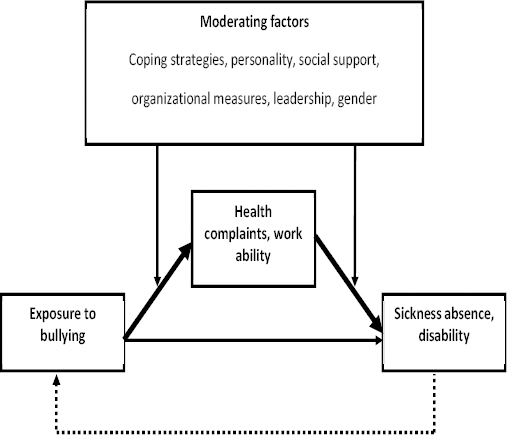

Figure 1 displays a theoretical model for how bullying may be related to sickness absence. The model proposes that bullying has an indirect effect on sickness absence through health complaints and reduced work ability (bold, solid line). That is, health complaints is a mediating variable that explain how bullying lead to sickness absence. Although we find it plausible that the main effect of bullying on sickness absence is mediated, it is also possible that bullying, in some cases, has a direct impact on sickness absence without going through health complaints or disability. For instance, sickness absence may be considered as a coping strategy used to protect the target of the impact of ongoing bullying. Others may be absent due to a belief that a break from work can help reduce the problem or make it go away.

Figure 1

Theoretical model for relationships between exposure to workplace bullying and sickness absence.

It is further assumed that the impact of bullying on sickness absence is conditioned by moderating factors. Theoretical models such as the transactional theory of stress and coping (24) and the cognitive activation theory of stress (25), place coping strategies as particularly important moderators in the relationship between bullying and health complaints. Personality dispositions and social support should also be considered as prominent moderator variables with regard to this specific association (26). Whether the health complaints caused by bullying subsequently leads to sickness absence will be especially dependent upon organizational level factors such as leadership, organizational support, and measures directed towards exposed employee (27). The same health complaints may therefore have different associations with work ability pending on organizational conditions. In line with the consistent higher sickness absence rates among women than among men (28), gender is also a potential moderating variable as it is likely that women are more prone to having absence compared to male employees.

As illustrated with the dashed line in Figure 1, it is also possible that sickness absence can impact on subsequent exposure to bullying. Coworkers could perceive sickness absence as a negative, and lead to hostile behavior or social exclusion from colleagues and superiors upon return to work (29). Long-term sickness absence could also influence the perceptions and attitudes of the absentee, with lowered threshold for experiencing events at the workplace as bullying.

Our theoretical model suggests that bullying may have indirect (mediated), conditional (moderated) and reverse associations with sickness absence. In some cases, a direct forward association is also possible. By providing a systematic overview of findings on bullying and sickness absence, an overarching aim of this review is to determine if there is evidence to elucidate the elements of this theoretical model. The overall magnitude of the association between exposure to bullying and sickness absence will be established by means of a meta-analytic synthesis. The research questions are: (i) Is exposure to workplace bullying related to an increased risk of subsequent sickness absence among employees? (ii) Is sickness absence related to an increased risk of subsequent exposure to workplace bullying? (iii) What are the mediating and moderating factors that govern the relationship between workplace bullying and sickness absence?

Methods

The review was structured in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines (30). There is no published or registered review protocol for this study. The quality of evidence for an association between bullying and sickness absence was evaluated in accordance with the GRADE system (10). This system grades quality of evidence at four levels: High (4), moderate (3), low (2), very low (1). For high evidence, the requirements are a randomized, double-blinded study design with no selection biases. For observational studies, moderate evidence (ie, exceptionally strong evidence from unbiased studies) is considered the strongest possible level of proof for an association.

Search strategy

This literature review and meta-analysis was based on systematic searches in Oria (http://www.oria.no). This search engine performs simultaneous searches in 20 literature databases, including Medline/PubMed, Proquest, Web of Science, Taylor & Francis Online Journals, and Wiley Online Library. Additional searches were performed in PsycINFO and Google Scholar. Systematic searches were performed by combining every possible combination of three groups of keywords. The first group comprised the keywords “Work”, “Work*” and “Job”. The second group comprised the keywords “mobbing”, “bullying”, “victimization”, and “harassment”. The final group consisted of “Absenteeism”, “Sickness”, “Absence”, “Sick-leave” and “Sick-listing”. The literature search was finalized 30 November 2015. The searches were not limited by historical time-constraints. The systematic procedure substantiates that the literature search comprises all published studies on the relationship between workplace bullying and sickness absenteeism. The search strategy was considered as adequate to reduce the risk of selection and detection bias.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

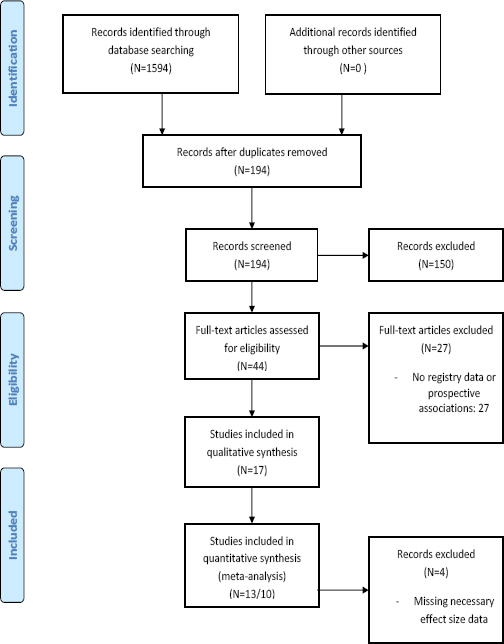

Primary studies with prospective research design and studies that incorporated registry data on sickness absence were included in the review. Cross-sectional primary studies based on self-reported sickness absence were excluded since this design increases risk of methodological bias and strongly challenges causal inferences. The review was limited to articles published in peer-reviewed journals in English or the Scandinavian languages (Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish). Hence, this is a review of published and peer-reviewed studies only. As a first step, relevant articles were considered on the basis of their title and abstract. In a second step, the fulltext versions of selected papers were examined. The results from the literature search are presented in Figure 2. Altogether 12 unique and relevant articles were identified through the searches in Oria (a detailed overview of this search can be downloaded from: https://dl.dropboxusercontent.com/u/69264552/Work/Oriasearch.pdf). A supplementary search in PsycINFO provided one unique and relevant article, whereas supplementary searches with Google Scholar resulted in six unique and relevant articles. Two of the identified papers were based on identical samples and were therefore included in the review as a single study (31, 32).

Quality assessment tool

The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed using a check-list consisting of 13 items related to sampling, representativeness, measurement issues, and confounders (see table 1). As there are no previous standardized quality assessment tools for observational studies on workplace bullying, the form was developed specifically for this study. Selected items from the Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for Nonrandomized Studies (33) and the Quality Assessment Tool (34) were used as a basis for the study tool. The quality of the reviewed studies was scored on a scale from 0 (lowest possible quality) to 13 (highest possible quality). The full tool can be downloaded from https://dl.dropboxusercontent.com/u/69264552/Work/QualityAssess.xlsx. The first and second author rated study quality.

Table 1

Checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality of the reviewed studies.

Meta-analytic approach

The meta-analysis was conducted using the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (version 2) software developed by Biostat (35). OR with 95% CI is reported as an overall synthesized measure of effect size. The mean of the combined effect sizes was calculated in studies where several effect sizes were reported from the same sample (eg, models with different control variables). Four of the included studies used overlapping data from the Norwegian Living Conditions Survey (36–39). As these samples were dependent, an overall estimate was calculated in the meta-analysis on the basis of these studies. In studies that reported effect sizes from independent subgroups (eg, moderators), each subgroup was included as a unique sample in the meta-analysis. Only studies reporting effect sizes that could be converted to OR were included. As considerable heterogeneity was expected between studies, pooled mean effect size was calculated using the random effects model. Random effects models are recommended when accumulating data from a series of studies where the effect size is assumed to vary from one study to the next, and where it is unlikely that studies are functionally equivalent (40). Random effects models allow statistical inferences to be made to a population of studies beyond those included in the meta-analysis (41). The Qwithin statistic was used to assess the heterogeneity of studies. A significant Qwithin value rejects the null hypothesis of homogeneity. An I2 statistic was computed as an indicator of heterogeneity in percentages. Increasing values show increasing heterogeneity, with values of 0% indicating no heterogeneity, 50% indicating moderate heterogeneity, and 75% indicating high heterogeneity (42). Four indicators of publication bias were examined: Funnel Plot, Rosenthal’s Fail-Safe N, Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill procedure, and Egger’s Regression Intercept (43).

Results

Descriptive findings and assessment of methodological quality

An overview of the 17 included primary studies is presented in table 2. With the exception of one study from Belgium (44), all included studies originated from Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden). Thirteen studies had a prospective research design and included registry data on sickness absence (36–39, 44–52). Two studies used a retrospective design with registry data on sickness absence (31, 53). Two studies had a prospective design with self-reported sickness absence (54, 55). Operationalizations of sickness absence varied extensively between studies. Seven studies analyzed the risk of having at least one episode of sickness absence lasting for more than a given number of consecutive days (44–46, 48, 49, 52, 55). Eight studies analyzed the risk of having a total number of sickness absence days above a given cut-off value (36–39, 47, 50, 51, 53). One study analyzed the risk for being on sick leave at the time of the follow-up survey measurement (54), whereas one other study analyzed the risk for having at least two episodes of registered sickness absence during the last year before the survey (31). Three studies adjusted for previous sickness absence in the prospective analyses (46, 50, 52).

Table 2

Overview of studies included in the literature review.

| Authors, year (Reference) | Country | Study design | Score a | Time b | Operationalization sickness absence | N | Sample type | Assoc-iation c | Reverse relationship examined | Mediator/moderators included |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aagestad et al 2014 (36) | Norway | Prospective, registry-based absence | 10 | 12 | A total of ≥40 days (not consecutive) of medically confirmed sick leave during the follow-up | 6758 | Representative for working population | Yes | No | No |

| Aagestad et al, 2014 (37) | Norway | Prospective, registry-based absence | 10 | 12 | A total of ≥40 days (not consecutive) of medically confirmed sick leave during the follow-up | 925 | Employees in health care | Yes | No | No |

| Berthelsen et al, 2011 (54) | Norway | Prospective, self-reported absence | 10 | 24 | Whether the respondents were on sick leave at the follow-up measurement time point. | 1775 | Representative for working population | Yes | No | No |

| Clausen et al, 2012 (45) | Denmark | Prospective, registry-based absence | 9 | 12 | ≥1 instance of ≥8 consecutive weeks of sickness absence in the follow-up | 9520 | Female employees in elderly care | Yes | No | No |

| Eriksen et al, 2003 (55) | Norway | Prospective, self-reported absence | 11 | 3 | ≥1 instance of absence from work because of illness for >3 consecutive days during the follow-up | 4931 | Nurses | No | No | No |

| Hinnka et al 2013 (46) | Finland | Prospective, registry-based absence | 10 | 84 | One instance of medically confirmed sick leave for ≥9 consecutive days in the follow-up | 967 | Public employees | Yes | No | No |

| Janssens et al, 2014 (44) | Belgium | Prospective, registry-based absence | 9 | 12 | ≥1 instance of medically confirmed sick leave for ≥15 consecutive days in the follow-up | 2983 | Employees from seven different enterprises | Yes | No | Health complaints |

| Josephson et al, 2008 (47) | Sweden | Prospective, registry-based absence | 11 | 36 | ≥1 instance of sick leave for >28 days | 2293 | Nurses | Yes | No | No |

| Kivimäki et al, 2000 (52) | Finland | Prospective, registry-based absence | 12 | 12 | Short: ≥1 self-certified instance of sick leave for 1–3 days Long: ≥1 instance of medically certified sick leave for >4 consecutive days during follow-up | 5655 | Hospital employees | Yes | No | No |

| Laaksonen et al (2007) (48) | Finland | Prospective, registry-based absence | 10 | 21 | Short: ≥1 instance of absence of 1–3 days Long: ≥1 instance of sick leave for >3 consecutive days during follow-up | 6838 | Representative for urban municipality | Yes | No | Obesity |

| Ortega et al, 2011 (49) | Denmark | Prospective, registry-based absence | 11 | 12 | ≥1 instance of sick leave for >6 consecutive weeks during follow-up | 9949 | Elderly care | Yes | No | No |

| Sterud, 2014 (38) | Prospective, registry-based absence | 10 | 12 | A total of ≥40 days (not consecutive) of medically confirmed sick leave during the follow-up | 12 255 | Representative for working population | Yes | No | No | |

| Sterud & Johannessen, 2014 (39) | Norway | Prospective, registry-based absence | 10 | 12 | A total of ≥40 days (not consecutive) of medically confirmed sick leave during the follow-up | 6758 | Representative for working population | Yes | No | Gender and educational level |

| Strømholm et al, 2015 (50) | Norway | Prospective, registry-based absence | 11 | 12 | A total of ≥28 days (not consecutive) of medically confirmed sick leave during the follow-up | 21834 | Representative for a county | Yes | No | Gender and diagnoses |

| Suadicani et al 2014 (53) | Denmark | Retrospective, registry-based absence | 10 | 12 | Registered sickness absence of ≥14 days during follow-up | 1809 | Hospital employees | Yes | No | No |

| Vingård et al, 2005 (51) | Sweden | Prospective, registry-based absence | 9 | 36 | ≥1 instance of sick leave for >28 days | 6246 | Female employees in public sector | Yes | No | No |

| Voss et al, 2001, 2004 (31, 32) | Sweden | Retrospective, registry-based absence | 10 | 12 | ≥2 episodes of registered sickness absence during the year prior to the study | 3470 | Postal employees | Yes | No | Gender and complaints due to heavy lifting |

The average number of participants in the included studies was 5831 (range: 925–21 834). Four studies were based on nationwide representative samples of the working population (36, 38, 39, 54), whereas one study included data representative of a county (50). Seven studies included respondents from healthcare occupations (37, 45, 47, 49, 52, 53, 55). The remaining five studies were based on public employees (46, 51), employees in an urban municipality (48), postal employees (31), and employees from mixed occupational groups (44). The time-lag between measurement time-points for studies using prospective research design varied between 3–84 months, although the majority of studies [10 studies (31, 36–39, 44, 45, 49, 50, 53] were based on 12-month time intervals.

The inter-rater agreement in the rating of methodological quality was very high (98% agreement). On the scale from 0–13, the methodological quality of the studies ranged from 9 (44, 45, 51) to 12 (52) with a mean score of 10.08 and a median of 10 (see table 2). The assessment showed a low risk of bias related to selection, representativeness, measurement, and confounders. The ratings suggest that the methodological quality of the included studied was high. All scores on all criteria for each reviewed studies can be downloaded from https://dl.dropboxusercontent.com/u/69264552/Work/Scoring.xlsx.

Relationships between bullying and sickness absence

A significant positive direct association between exposure to bullying and sickness absence were established in 16 out of 17 studies. The only non-significant relationship was established in a self-report study of Norwegian nurses using a 3-month follow-up period (55). In other studies, bullying was related to both short and long spells of absence. As an illustration, Clausen and colleagues (45) found that bullying predicted sickness absence of >8 weeks among employees in elderly care with a risk ratio of 2.26 (95% CI 1.50–3.42) after adjusting for threats, violence, unwanted sexual attention, psychosocial work environment, and demographical factors. Similar associations were found in other studies among healthcare employees using shorter incidences of sickness absence as outcome (47, 49, 52).

None of the included studies presented data on the impact of sickness absence on subsequent risk of workplace bullying (the reverse association). Further, none of the studies included mediating variables to explain how bullying leads to sickness absence. All of the reviewed studies included one or more confounding factors, control variables, or other work exposures (eg, job demands, decision latitude, role expectations etc). In all but two studies (36, 37), the association between bullying and sickness absence remained significant after adjusting for covariates. Five studies examined variables that moderated the relationship between bullying and sickness absence: gender (31, 39, 50), obesity (48), health complaints (44), medical diagnoses (50), complaints due to heavy lifting (31), and educational level (39). As for educational level, the moderator analyses showed a somewhat stronger association between bullying and sickness absence among employees with low educational level. Bullying predicted sickness absence among both men and women, and the results do not provide robust evidence for any gender differences in the association. Still, one study found that the association between bullying and subsequent sickness absence was only significant for women (31, 32). In two other studies, the association between the variables was only maintained for women, and not men, after adjusting for covariates (39, 50). One study showed that bullying was most strongly associated with sickness absence among obese persons (48). In a study that examined medical diagnoses as moderator, the findings showed that bullying was related to sickness absence among respondents with mental health complaints and “other reasons for sickness absence”, whereas bullying was not related to absence among respondents diagnosed with cardiovascular illness or musculoskeletal complaints (50).

Four of the studies from Norway reported associations from the annual Living Conditions Survey carried out by Statistics Norway (36–39) and were based on partly overlapping samples. As a consequence, these studies present findings on the association between bullying and sickness absence based on related data. Differences in the magnitude of the associations in these studies are explained by different operationalizations of sickness absence, differences in covariates, as well as some variations in the samples.

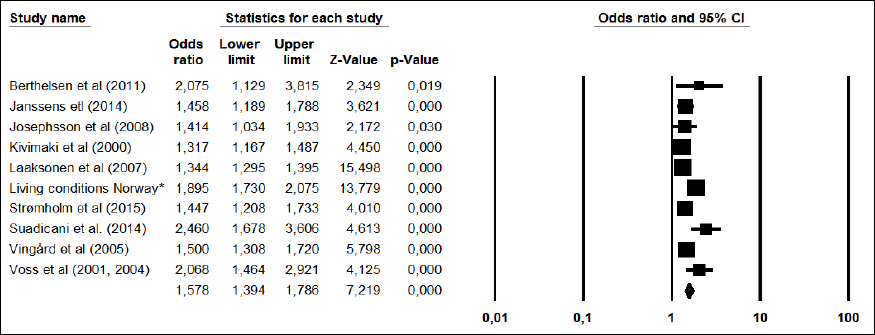

Meta-analysis

Findings from the meta-analysis are presented in table 3 and figure 3 (forest plot). A synthesis of 10 independent samples provided an overall average OR of 1.58 (95% CI 1.39–1.79). High levels of heterogeneity were established for the effect sizes included in this overall estimate (Qwithin 63.07, P<0.001, I2=85.73). The Fail Safe N indicated that 941 missing studies are needed in order to make the overall estimate non-significant. Following the recommendations for interpretations by Sterne and colleagues (56), a funnel plot indicated relative symmetry in the included studies, thus suggesting that the established estimate is comparable to population effect. The Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill procedure indicated that there were no missing studies to the right of the mean, but one missing study to the left of the mean. This shifted the overall estimate to 1.53 (95% CI 1.36–1.73). Following Egger’s regression test, the intercept was not significantly different from zero (B0=1.94, 95% CI -0.59–4.46), thereby indicating that the estimate is not influenced by potential publication bias.

Table 3

Meta-analytic findings on relationships between workplace bullying and subsequent sickness absence (Random effects model) [K=number of independent samples; mean OR=average weighted odds ratio; 95% CI=95% confidence interval].

| K | Mean OR | 95 % CI | Q | I2 | Tau | Tau2 | Fail Safe N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall estimate | 10 | 1.58 | 1.39–1.79 | 63.07 a | 85.73 | 0.16 | 0.03 | 941 |

| Adjusted estimates | ||||||||

| Crude | 6 | 1.70 | 1.43–2.02 | 14.37 b | 65.21 | 0.16 | 0.03 | 168 |

| Demographic factors | 6 | 1.54 | 1.29–1.85 | 13.54 b | 63.06 | 0.17 | 0.03 | 87 |

| Demographic and other work exposures | 6 | 1.53 | 1.29–1.81 | 49.39 a | 89.88 | 0.18 | 0.03 | 466 |

As indicated by the overlapping CI (table 3), separate analyses for crude association between bullying and sickness absence, for associations adjusted for demographic factors and associations adjusted for demographic and work factors, all provided estimates in line with the overall estimate. A moderator analysis showed that the difference in magnitude of the associations between bullying and sickness absence was non-significant (Qbetween 2.92, df=1, P=0.09) when comparing studies using follow-up periods up to one year (K=6, OR 1.67, 95% CI 1.39–1.99) to studies with periods longer than one year (K=4, OR 1.40, 95% CI 1.28–1.53). Due to lack of statistical power, it was not possible to determine the impact of other moderator variables.

Discussion

Following the GRADE guidelines (10), the quality of evidence for an association between workplace bullying and subsequent sickness absence can be rated as moderate. Hence, the findings from this systematic literature review and meta-analysis provide robust evidence for exposure to workplace bullying as an antecedent to sickness absence. Across all studies, respondents exposed to bullying showed a 58% higher odds (OR 1.58) for having had sickness absence compared to their non-bullied colleagues. As sickness absence was assessed with different criteria in the included primary studies, this overall estimate does not provide information about number of leaves or the specific length of the absence. Analyses of publication bias indicated that this kind of bias was not present in the meta-analysis. Compared to findings from a previous meta-analysis on predictors of sickness absence (3), our findings show that workplace bullying is more strongly associated with absence than other work factors, including high job demands (OR 1.15), low job control (OR 1.28), low decision latitude (OR 1.33), and experiencing no fairness at work (OR 1.30). In the current study, bullying was related both to short- and long-term sickness absence and within both shorter (≤1 year) and longer (>1 year) follow-up periods. The meta-analysis showed that the association between bullying and absence remained consistent after adjusting for demographic factors and other work-related exposures. This suggests that bullying has a unique contribution to the variance in sickness absence. However, it should be noted that the number of studies that constitute the knowledge base is limited.

In the theoretical model presented in the introduction of this paper, we argued that bullying could have direct, indirect, conditional, and reverse associations with sickness absence. With the exception of five studies, where one or more moderating variables were included, all of the included studies assessed direct associations between the variables. The impact of health complaints as mediating variable is therefore not yet examined. However, in an Australian study on depression-related sickness absence, it was found that depression attributable to bullying was associated with productivity loss in the form of sickness absence, thus showing depression as a potential mediator (57). Specifically, the authors calculated a population-attributable risk (PAR) estimate of 8.7% for depression attributable to bullying and job strain, equating to $AUD693 million in preventable lost productivity costs per annum. As this study did not include any direct links between bullying and sickness absence, it was not included in this systematic review. As only a limited number of moderating variables have been examined, we are still short of knowledge about conditional factors. In addition, as none of the studies included in the review examined the potential reverse impact of sickness absence on workplace bullying, it is still unknown whether absence might increase risk for later exposure to bullying. Taken together, the existing knowledge base makes it impossible to draw valid conclusions about how and when bullying is related to sickness absence.

The majority of the studies included in this review examined associations between bullying and sickness absence with a one-year time-lag. Both from a conceptual and methodological perspective it may be questioned whether one year is an optimal time-lag for identifying relationships between exposure to bullying and sickness absence. With regard to research design, it is suggested that 2–3-year time-lags are better suited to study associations between work factors and health (58), and conclusions based on a 1-year lag may therefore lead to an underestimation of the actual impact of bullying. As for conceptual issues, bullying is a process that often develops and escalates over time, and it is therefore reasonable that the most detrimental effects may first occur after long-term exposure. This might be particularly relevant if we assume that the true causal mechanism requires the bullying to first initiate, intensify, before it gradually translates to health complaints for the target. It also takes time for the health complaints to develop and translate to reduced work ability, upon which personal and occupational measures to solve the problem is set in motion and found unsuccessful with sickness absence as the result. Many targeted employees will likely attempt other coping strategies before resorting to sickness absence. Hence, in line with a so-called “sleeper effect” (59), it seems likely that sickness absence will first occur after prolonged exposure to bullying and it may be necessary to employee longer timeframes, for instance 2–5 years, in order to determine the actual effect of bullying.

However, going against the arguments for a delayed effect of bullying on absence, the findings from the current meta-analysis show that bullying had an equally strong association with subsequent absence in studies that were based on follow-up period of ≤1 year as in studies with longer follow-up periods (≤84 months). While these findings do suggest that the impact of bullying is relatively immediate, it should be noted that only a few studies employed follow-up periods beyond two years. In addition, as none of the studies included information about duration of the exposure to bullying before participating in the surveys, it is difficult to determine the actual impact of time on the association between bullying and sickness absence.

Although previous research on sickness absence have established persistent differences in absence rates among women and men, only three of the studies included in this literature review examined the relationship between bullying and absence by separating on gender. Analyzes of gender differences in the other included studies may have provided a more nuanced picture of bullying as risk factor for sickness absence.

Methodological quality

The methodological quality of the studies included in this review was high and there was a low risk of bias related to selection, representativeness, measurement, and confounding variables. All studies were based on large samples based on general working populations or specific occupational groups, such as health care workers. Most samples were based on a probability selection of participants. The established positive association between bullying and sickness absence was consistent across samples and occupations. This suggests that the findings have high external validity. Both bullying and sickness absence are relatively low prevalent phenomena. As all studies were based on large samples, they seem to have satisfactory statistical power with regard to examine the relationship between the variables. A methodological limitation of the included studies was that the operationalizations of sickness absence varied extensively between studies. Consequently, some of the variation in the estimated risk of sickness absence may be due to the differences in these operationalizations.

It is also a significant strength that the majority of studies employed registry-based sickness absence as a dependent variable. This reduces the likelihood for the impact of reporting bias on the sickness absence rates. It should be noted that unmeasured subjective factors such as personality traits and emotional states may have colored reports of bullying as may have certain other unmeasured confounding factors. Nonetheless, both work environment factors, such as job demands and control, and demographical characteristics were included as control variables in most of the studies and it should be noted that findings from the meta-analysis showed that the associations between bullying and sickness absence were consistent across unadjusted and adjusted estimates.

Concluding remarks

As exposure to workplace bullying is associated with an increased risk of both mental and somatic health complaints it is reasonable to expect that bullying also is a risk factor for sickness absence. This literature review and meta-analysis of research on bullying and sickness absence supports this expectation as the majority of studies, as well as their synthesized estimates, showed a positive association between bullying and subsequent sickness absence. The reviewed studies had high methodological quality and the results were consistent across studies and generalizable.

However, a significant limitation of existing research is that most studies have only examined direct forward associations between bullying and absence. Consequently, there is a shortage of knowledge about the mechanisms and conditions that govern the association between the variables. Another limitation of previous research is that no studies have established whether sickness absence can be a risk factor for later exposure to workplace bullying. Finally, most studies have examined bullying and sickness absence within relatively short time-frames and little is known about the long-term impact of bullying on absence.

Based on the results from this review, we know that bullying predicts sickness absence. A challenge for upcoming research in this field will therefore be to identify mediating and moderating variables to explain how and when exposure to bullying results in sickness absence. We have, in our theoretical model, proposed some factors that can and should be included in future research. Upcoming studies on bullying and absence should, if possible, include registry data on sickness absence as these provide the most valid and objective representation of actual absence rates (60). Furthermore, future studies should examine bullying and sickness absence with longer time-lags in order to establish the long term effects of bullying. To be able to develop a more comprehensive understanding of the associations, reversed associations between the variables should also be examined. Finally, as all, but one, of the reviewed studies originated from the Nordic countries, there is a need for studies on bullying and absence based on data from other countries.

The findings of this review have some important implications. The established relationship between bullying and sickness absence shows that bullying has detrimental consequences both for exposed employees and for organizations in which the bullying occurs. Hence, the findings support previous claims about bullying as a severe problem in the psychosocial working environment (9). The results do also support the assumption that measures against bullying and harassment can contribute to reduce sickness absence. However, a more nuanced picture of mechanisms and conditional factors which can explain how and when bullying is related to absence is necessary in order to develop effective measures and interventions for targeting bullying and absence.