Injuries and musculoskeletal disorders (especially low-back pain and neck/shoulder pain) due to moving and handling of people (MHP) are a long-term concern in the healthcare sector (1–7). Providing the healthcare sector with comprehensive information on MHP in the form of guidelines is a strategy widely applied globally, with multiple state or federal MPH guidelines existing in Europe, the US, and Australasia (4, 8, 9). It is assumed that this strategy may reduce MHP-related injuries and musculoskeletal disorders (10–13). However, it is unclear how effective MHP guidelines are, with some studies showing reduced injury rates (14–16), and others showing no difference (17).

In New Zealand, a national MHP guideline was launched by the Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC) in 2012: the Moving and Handling People: The New Zealand Guidelines (MHPG) (18). The MHPG provides guidance on implementing a multifaceted intervention program comprising two focus areas: (i) organization of the MHP program, consisting of MHP policy, workplace culture, monitoring, evaluation and audit, and; (ii) key elements of the MHP program, consisting of risk assessment, MHP techniques, MHP training, MHP equipment and management, and facility design (19).

The MHPG replaced earlier guidelines published in 2003 (20), which had a single focus on MHP techniques and training. The purpose of the new 2012 MHPG was to reduce health and safety risks related to MHP resulting in fewer injuries and a reduction in claims rates and costs (19). The MHPG targeted all sub-sectors of the healthcare sector, but with a specific focus on public hospitals, as they were seen as the main drivers of change in the healthcare sector (19).

The study presented in this paper is nested in a larger project that evaluated the uptake, use, and impact of the MHPG, through a mixed-methods approach. The specific aims of the present study were to: (i) establish the accepted claims rates, costs, and causes for MHP-related injuries in the healthcare sector of New Zealand for the period 2005‒2016; and (ii) assess temporal changes in claims rates, costs, and causes following the launch of the MHPG in 2012. We tested the hypothesis that the introduction of the MHGP would result in a decrease in injury claims rates and costs related to MHP. Injury claims in this paper are covered by the definitions in the New Zealand Accident Compensation Act 2001 (21). Accepted claims cover personal injuries caused by an accident to the person and personal injury caused by a work-related gradual process (Accident Compensation Act 2001, section 20). The definition of a personal injury includes: the death of a person; or physical injuries suffered by a person, including, for example, a strain or a sprain (Accident Compensation Act 2001, section 26).

Methods

Design

The study examined injury data from the ACC’s injury claims database, which contains information about accepted work-related injury claims for all employers in New Zealand and uses 40 different injury causes. The injury reporting forms have an ‘accident description’ field to describe how the injury occurred, which is the only way to relate an injury claim to MHP. However, it is not compulsory for all employers to fill in this field. In particular, ACC accredited employers are not required to do so because they manage and pay compensation related to their own claims. Accredited employers are part of an ACC scheme in which large employers can substantially reduce ACC levies by maintaining a high health and safety management standard, which an external auditor assesses annually.

The Massey University Human Ethics Committee approved the study (SOB 15/78), which was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Data collection

We included all accepted injury claims recorded in the ACC injury claims database between 2005‒2016 for 14 Australian and New Zealand standard industrial classification (ANZSIC) codes (2006; level 4), which were assumed to involve MHP. The 14 ANZSIC codes were: labor supply services (N7212); hospitals (except psychiatric hospitals) (Q8401); general practice medical services (Q8511); specialist medical services (Q8512); pathology and diagnostic imaging services (Q8520); physiotherapy services (Q8533); chiropractic and osteopathic services (Q8534); other allied health services (Q8539); ambulance services (Q8591); other healthcare services (Q8599); aged care residential services (Q8601); other residential care services (Q8609); child care services (Q8710); and other social assistance services (Q8790).

ACC’s database does not include number of employees. For this, we retrieved number of fulltime equivalent employees for the period 2005‒2016 from Statistics New Zealand’s ‘Business demography statistics’, ‘Enterprises by institutional sector and employee count size 2000‒16’ (nzdotstat.stats.govt.nz/wbos/Index.aspx) (accessed June 2017).

Data analysis

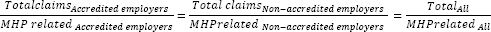

One researcher assessed the accident description field of all included injury claims to identify if a claim was related to MHP and then discussed with the research group to obtain consensus. All claims related to MHP were included. However, very few claims from accredited employers included an accident description. Thus, we used an estimate for the MHP-related claims for accredited employers. For this, we developed adjustment factors, which were calculated on the assumption that the proportion of MHP-related claims is the same for accredited and non-accredited employers. Hence assuming that if the proportion of MHP claims, compared to all claims, goes up for the non-accredited employers, the same would happen for the accredited employers, in relation to the total claims for the accredited employers, thereby creating a more realistic claims rate. The relationship was expressed by the following equation:

From this equation the total number of MHP-related injury claims was calculated as:

The adjustment factor (AMHP) was expressed by:

This adjustment factor was used to estimate both claims numbers, claims rates, claims costs, and claims cause. The adjustment factors were calculated for each year and are shown in supplementary tables S1a and S1b for ANZSIC code and injury (www.sjweh.fi/show_abstract.php?abstract_id=3818).

Claims rates were expressed per 1000 employees and were calculated by dividing claim numbers by employee count.

In order to assess claim costs for a specific point in time, the total costs for each claim was allocated to the year in which the claim was lodged regardless of the length of the claim. For example, a claim with a total cost of NZ$4500 for the period 2007–2009 would have the entire cost of the claim allocated to 2007.

Causes of claims were identified from the ACC database. Any cause that appeared to have even a remote likelihood of being related to MHP was included. Thus 12 claims causes possibly related to MHP were considered: lifting/carrying/strain; loss of balance/personal control; loss of hold; misjudgment of support; other or unclear cause; pushed or pulled; slipping, skidding on foot; something giving way underfoot; struck by person/animal; tripping or stumbling; twisting movement; undefined cause.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (SPSS version 25.1, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). An interrupted time series analysis using an AMIRA model (22, 23) was used to analyze the data for claims rates and costs stratified by industry as well as for claims causes. The analysis provided the yearly changes and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the period before and after the introduction of the MHPG, as well as the difference in slope. Further, the analysis examined changes at one, two, three, and four years following the introduction of the guidelines by comparing the actual values for these four time points with values predicted by extrapolation of the of the linear regression line for the period before the introduction. Statistical significance was defined as P<0.05.

Results

Claims rates and claims costs for all industries

A total of 118 755 injury claims for the period 2005–2016, with a total cost of NZ$ 225 356 400, were included. Of these, 68 662 (58%) originated from non-accredited employers. Based on accident descriptions of claims originating from non-accredited employers, 22 900 (33.0% of all claims from non-accredited employers) were related to MHP. Using correction factors, it was estimated that in total (including those from accredited employers) 39 209 claims were related to MHP ie, an average of 3267 claims/year. The two industries contributing most to the total number of MHP-related claims were ‘aged care residential services’ and ‘hospitals’ with 14 707 and 13 134 claims respectively (supplementary tables S1a and S1b). Total cost for injury claims related to MHP was estimated to be NZ$ 93 756 789, with an average cost of NZ$ 7 813 066/ year.

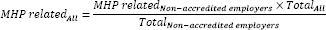

There was a significant decrease in claims rates of 0.4 claims/ 1000 employees per year (95% CI -0.5‒ -0.2) before the introduction of the MHPG, but no change was seen following the introduction (0.0 claims/1000 employees per year; 95% CI -0.4‒0.4) (figure 1a). However, compared to predicted claims rates, there were significant increases in claims rates after two years (1.3; 95% CI 0.4‒2.2), three years (1.6; 95% CI 0.7‒ 2.8), and four years (2.0; 95% CI 0.8‒ 3.1) following the introduction of the MHPG (Tables 1a and 1b).

Figure 1

Moving and handling people (MHP)-related injury claims rates (1a) and costs (1b) per year for the period before (2005-2012) and after (2013-2016) the introduction of the MHP guidelines and associated regressions lines. ♦ indicates yearly costs before (2005-2012) and ▄ after (2013-2016) the introduction of the MHGP. * represents a significant P-value ≥0.05.

Table 1a

Interrupted time series analysis of claims rates (2005‒2016). [CI=confidence interval; MHP=moving and handling of people.]

Table 1b

Interrupted time series analysis of claims rates (2005‒2016) continued. [Δ=change in claims rate compared to predicted level; CI=confidence interval; MHP=moving and handling of people.]

There was a significant yearly decrease in mean claims costs of NZ$ 230 (95% CI -324.1‒ -136.0) before the introduction of the MHPG, but no significant yearly change for the period following the introduction (NZ$ 23.7; 95% CI -300.5‒348.0) (figure 1b). However, similar to claims rates, there were significant yearly increases compared to predicted costs after three years (NZ$ 724; 95% CI -2‒1451) and four years (NZ$ 987; 95% CI 88‒1886) following the introduction of the MHPG (Tables 2a and 2b).

Table 2a

Interrupted time series analysis of claims costs (2005‒2016). [CI=confidence interval; MHP=moving and handling of people.]

Table 2b

Interrupted time series analysis of claims costs (2005‒2016) continued. [Δ=change in claims costs compared to predicted level (NZ$); CI=confidence interval; MHP=moving and handling of people.]

Claims rates per industry

Supplementary tables S1a and S1b show claims rates stratified by industry per year for 2005‒2016. The highest mean claims rates were found for ‘ambulance services’ (50.8) and ‘aged care residential services’ (36.9). Prior to the introduction of the MHPG, there were decreases in claims rates for four industries: ‘labor supply services’, -0.2/1000 (95% CI -0.4‒ -0.1); ‘hospitals’, -0.4/1000 (95% CI -0.9‒ -0.0); ‘specialist medical services’, -3.2/1000 (95% CI -3.5‒ -3.0); and ‘aged care residential services’, -1.5/1000 (95% CI -2.1‒ -0.8) (tables 1a and 1b, and supplementary figure S1, www.sjweh.fi/show_abstract.php?abstract_id=3818). There were increases for two industries: ‘pathology and diagnostic imaging services’, 0.4/1000 (95% CI 0.0‒0.8), and ‘other healthcare services’, 1.0 /1000 (95% CI 0.1‒1.8). In the period following the introduction of the MHPG, there was only one industry with a significant yearly change in claims rate ie, ‘labor supply services’, 0.4/1000 (95% CI -0.1‒0.9). In contrast to the overall decrease before the introduction of the MHPG, there were increases in claims rates compared to the predicted claims rate for several industries following the introduction (tables 1a and 1b).

Claims costs per industry

Supplementary tables S1a and S1b show the average claims cost per claim stratified by industry per year for 2005‒2016. The highest mean claims cost during this period were found for ‘pathology and diagnostic imaging services’ (NZ$ 4318), ‘ambulance services’ (NZ$ 3350), and ‘labor supply services’ (NZ$ 3157). In the period before the introduction of the MHPG, three industries had a decrease in claims costs: ‘pathology and diagnostic imaging services’, NZ$ -3795 (95% CI -7524‒ -67); ‘aged care residential services’, NZ$ -300 (95% CI -547‒ -52); and ‘other social assistance services’, NZ$ -626 (95% CI -817‒ -435) (tables 2a and 2b, and supplementary figure S2). In the period following the introduction of the MHPG, only ‘other health care services’ had a significant change, with an increase in yearly change in claims costs of NZ$ 323 (95% CI 179‒467). Following the introduction of the MHPG, there was a significant increase in claims costs compared to the predicted costs for one industry, ie, ‘other social assistance’, and a significant decrease in claims costs compared to the predicted costs for another industry, ie, ‘other healthcare services’.

Claims causes

Supplementary table S2 shows claims numbers stratified by claims causes for 2005‒2016. The largest single cause of injury related to MHP was lifting/carrying/ strain (65.3%). In combination with loss of balance/ personal control (6.8%), twisting movement (4.5%), struck by person/animal (3.5%), and pushed or pulled (3.3%), these five causes accounted for >83% of all claims. A substantial proportion of claims were caused by other or unclear cause (13.2%).

Prior to the introduction of the MHPG, the claims numbers decreased for one cause: lifting/carrying/ strain, ie, -347 claims/year (95% CI -65.5‒ -3.9) (tables 3a and 3b, and supplementary figure S3, www.sjweh.fi/show_abstract.php?abstract_id=3818). In contrast, the claims numbers increased for four causes: misjudgment of support (6.4/year; 95% CI 1.7‒11.0); pushed or pulled (10.5/year; 95% CI 2.9‒18.1); tripping or stumbling (0.9/year; 95% CI 0.1‒1.8), and twisting movement (14.6/year; 95% CI 0.4‒28.8). There were no statistically significant differences in the period following the introduction of the MHPG.

Table 3a

Interrupted time series analysis of claims causes (2005‒2016). [CI=confidence interval; MHP=moving and handling of people.]

Table 3b

Interrupted time series analysis of claims causes (2005‒2016) continued. [Δ=change in claims number compared to predicted level; CI=confidence interval; MHP=moving and handling of people.]

One year following the introduction of the MHPG, there was a significant increase in claims number for lifting/carrying/strain (431.7/year; 95% CI 147.4‒ 716.0). Further, two, three, and four years following the introduction of the MHPG there were significant increases in claims number for two causes: lifting/carrying/strain of 485.8 (95% CI 247.6‒724.0), 539.9 (95% CI 306.9‒773.0), and 594.0 (95% CI 322.9‒865.2), respectively, and something giving way underfoot of 2.0 (95% CI 0.5‒3.6), 3.3 (95% CI 1.2‒5.5), and 4.6 (95% CI 0.6‒8.6), respectively. In contrast, two, three, and four years following the introduction of the MHPG, there were significant decreases in claims number for two causes: misjudgment of support of 34.1 (95% CI -67.9‒ -0.3), 39.5 (95% CI -75.0‒ -4.1), and 45.0 (95% CI -87.4‒ -2.5), respectively, and other or unclear cause of 140.3 (95% CI -264.5‒ -16.1), 156.1 (95% CI -289.5‒ -22.6), and 171.8 (95% CI -337.4‒ -6.3), respectively.

Discussion

This study found no reduction in claim rates and costs of MHP-related injuries following the introduction of the MHPG in 2012. In contrast, there were statistically significant increases in claims rates and costs. Approximately one-third of all injury claims in 2005–2016 in the healthcare sector in New Zealand were related to MHP. This is consistent with a recent study showing that more than one-third of all injury claims in large American nursing homes were related to MHP (14). Further, on average, our study estimated that 3267 injuries per year were related to MHP, contributing to a cost of nearly NZ$8 million per year.

Claim rates and costs before the introduction of the MHPG

Prior to the introduction of the MHPG, overall claim rates and costs significantly declined, which was largely driven by industries with the largest number of MHP-related injury claims: ‘aged care residential services’ and ‘hospitals’, as well as ‘labor supply services’, and ‘specialist medical services’. In contrast, a significant increase was observed for some of the smaller industries (‘pathology and diagnostic imaging services’, ‘other healthcare services’, and ‘other social assistance services’). Possible explanations for the decrease in claims and costs, especially seen within ‘aged care residential services’ and ‘hospitals’, include: (i) the healthcare sector implementing MHP programs that have helped reduce MHP and related risks resulting in reduction of MHP-related injury claims and related costs and/or; (ii) a decline in reporting of MHP-related injuries. The claims rate of 15.0 per 1000 employees for hospitals found in this study is comparable to an American study that reported an injury rate of 2.1 per 100 FTE, equivalent to 21 injuries per 1000 FTE, prior to the introduction of a minimal patient lifting policy in a tertiary hospital (24).

The effect of the introduction of the MHP guidelines

Following the introduction of the national MHPG, no overall change was observed for claims rate or costs. However, from the second year, claim rates gradually increased across all industries and, in the third and fourth year, claims costs increased across all industries. According to the program theory of the MHPG (19), the public hospitals were the target industry. Hence ‘hospitals’ were expected to experience the greatest impact from the MHPG. However, no decline in claims rates occurred for ‘hospitals’. In contrast, ‘aged care residential services’ as well as ‘labor supply services’, ‘specialist medical services’, and ‘physiotherapy’ had increasing claims rates in the years following the introduction. In addition, no change was observed in claims costs for ‘hospitals’ or any other industries, with the exception of ‘other healthcare services’.

One potential explanation for why an increase ‒ rather than a decrease ‒ was observed in claims and costs may be the increased awareness of MHP amongst MHPG users. This may have resulted in greater acceptance of MHP as a risk factor for injuries, increasing the likelihood of lodging MPH-related injury claims, both at an individual and at an organizational level. This may have led to an increase in accepted claims, even if the actual level of MHP-related injuries may not have changed. Alternatively, other national events and interventions related to occupational health and safety may have influenced reporting of injuries. In 2010, New Zealand experienced a mine explosion that killed 29 men, which initiated a review of how occupational health and safety was regulated in New Zealand (25, 26). As a result, in 2015 new health and safety legislation was passed that increased the focus on management’s liability. This may have affected claims rates, possibly masking a potential positive effect of the MHPG. Another explanation could be that potential positive effects of the MHPG have been counteracted by other factors. In particular, the population is getting increasingly heavy (27) and the proportion of bariatric patients is increasing (28). At the same time, the healthcare sector has an aging workforce. This may increase the risk of injuries related to MHP. Furthermore, there have been several budget cuts in the healthcare sector in New Zealand in the period 2009-2015 (29), increasing the workload on the remaining staff. In addition, the lack of improvement in MHP-related injury rates following the introduction of the MHPG could be the consequence of both poor implementation, eg, the MHPG not reaching the intended users or the industry not being able to implement the MHPG, and program failure, eg, the MHPG not working as expected. Lastly, the increased claims rates and costs could be completely unrelated to MHP. Previous studies have reported that differences in musculoskeletal disorders across various countries could not be explained by occupational factors, hence indicating that other factors play a prominent role for claims rates and costs (30, 31). However, the present study looked at the same population and only at changes in injury claims related to MHP according to the injury description. It is therefore likely that the above explanation is minimal in relation to our analysis.

Comparisons with similar studies

The finding of an increase in claims rates following the introduction of the MHPG differs from that of an evaluation of a ’No-Lift’ policy intervention combined with funding opportunities for equipment in the Australia state of Victoria by Martin et al (15). This study reported a decrease in MHP-related back injury claim rates of 0.79 per 1000 employees following implementation of the intervention (15). The discrepancy between the findings of the studies may be due to the availability of dedicated funding for the healthcare industry in the Australian state-level intervention (15). In contrast, in New Zealand the MHPG had no such supplementary funding, which may have been a barrier for effective implementation.

Kurowski et al (14) also found a reduction in MHP-related claims rate in large nursing homes following the introduction of a safe MHP program. A commercial risk management company administered this program, which consisted of risk assessment of residents, purchase of lifting equipment, and staff training. In the first three years following the introduction, claims rates were reduced from 93.0 to 63.3/1000 employees, and a further reduction to 57.4 was reported after six years (14). Powell-Cope and colleagues (16) also reported reductions in claims rate from 34.3 to 24.8/1000 employees five years following the implementation of a MHP program in a hospital network. The discrepancy with our study may be explained by the substantially higher initial claims rates of 93.0 compared to 36.9/1000 employees reported for ‘aged care residential services’ in our study, indicating a smaller potential for improvement. Additional factors that might help explain the different findings are differences in support from a commercial company for program implementation and assistance with purchase of equipment.

Our findings were more consistent with an evaluation by Schoenfisch and colleagues (17), following the introduction of a ‘minimal patient lifting policy’ consisting of lifting equipment purchases and training of MHP ‘champions’ in a tertiary hospital. They found no change in MHP-related injury claim rates following the introduction of a minimal patient lifting policy in a community hospital, but a 44% reduction in claims rate was observed following the introduction of lifting equipment in the hospital. This suggests that the availability of equipment plays a more critical role than an MHP policy. In addition, the economic evaluation of the same minimal patient lifting policy reported an immediate drop in mean cost of MHP-related injuries following the introduction of the minimal patient lifting policy (32). However, the authors speculated that this is due to a shift in budget responsibilities (towards unit managers holder responsibility) and not the introduction of the policy itself.

Claim causes

The majority of claim causes for MHP-related injuries were due to activities related to lifting/carrying/strain, loss of balance/personal control, twisting movement, struck by person/animal, and pushed or pulled. This finding is consistent with previous studies that have shown that lifting and carrying, pushing and pulling, and twisting are the main causes of MHP-related injuries (33–35). Of the five causes identified to be the main contributors to MHP-related injuries, lifting/carrying/ strain was the only cause that had a significant, gradual increase in claims numbers in the four years following the introduction of the MHPG. Together, these findings suggest that prevention of MHP claims should have a dedicated focus on these types of activities, especially activities related to lifting and carrying.

Strengths and limitations

The employee counts from Statistics New Zealand included all people in the specific industries and were not specific to people engaged in MHP. This might have influenced the claims rates so that an industry with a higher proportion of employees engaged in MHP might have a higher MHP-related injury claims rate, simply because more people are engaged in MHP. However, the proportion of people engaged in MHP within each of the industries would most likely be similar over time, so the temporal changes were not likely to be affected by that.

We estimated the total numbers of MHP-related claims based on the proportion of the non-accredited employers who fill in the accident description field on the forms submitted to ACC because most accredited employers did not complete this field. This introduced an uncertainty about the total number of injuries related to MHP. However, we consider this the best estimation possible. There has been no independent validation of claims data. To do so would be very difficult and require a separate study. The data in the present study are the best available, and there is no reason a priori to doubt them. Since the analysis examined the same dataset over time and only concludes on trends, it is valid to use the present data for this analysis.

The use of injury claim data may, as previously shown, underestimate the actual number of claims (36). One of the reasons for this is related to the criteria for deciding if a claim is included or not, eg, length of time away from work. As a consequence, injuries resulting in only short or no time away from work are not included (36). Further, vulnerable groups, such as unskilled, casual, or foreign workers, are less likely to lodge a claim due to the fear of losing their job (36). However, in this study, we have used the same source of data for the comparison before and after the introduction of the MHPG. Consequently, any underreporting of claims is unlikely to affect the before and after comparisons.

A particular strength of the present study was the narrative analysis of the ‘accident description’ included in the claims from non-ACC accredited employers. This approach afforded a detailed assessment of the individual claims in order to determine whether they were related to MHP.

Concluding remarks

Before the introduction of the national MHPG in New Zealand in 2012, MHP-related claim rates and costs declined. In contrast, in the four years after the introduction of the national guidelines, there were statistically significant increases in MHP-related claim rates and costs, suggesting that the introduction of the guidelines had not been effective in reducing MHP risks and injuries. The healthcare sector should particularly focus on addressing risk related to lifting/carrying/strain since the MHP injury claims caused by these causes were the only claims that increased after 2012.