In general, work is considered to be positive for mental health (1, 2). However, work can also be a potential risk factor for mental ill-health in that it might contribute to the development of and/or prolong a mental disorder (3). A mental disorder may lead to sickness absence and even to permanent work incapacity giving rise to the granting of a disability pension (DP) (3). In recent decades, the incidences of both mental disorders (4) and DP due to mental diagnoses (5) have increased. At present, mental diagnoses constitute the most common reason for DP (5, 6). Still, there is a lack of studies of work-related risk factors for being granted DP due to mental diagnoses (7).

Psychosocial working conditions can be risk factors of this kind and have often been measured using the Job Demand-Control-Support model (8–10). According to this model, jobs with high demands, low control, and/or low social support, and jobs with a combination of high demands and low control (high strain) and low social support (iso strain) are associated with increased risks of sickness absence/DP due to mental diagnoses (7, 11–18). In most of the previous studies of psychosocial working conditions, self-report surveys have been used to assess these factors (11, 15–19), but fewer studies have measured these working conditions by applying a validated job exposure matrix (JEM) (20–22), based on mean scores of job demands and control and social support in different occupations. Moreover, only a few previous studies are based on population-based cohorts (23), which limits the generalizability of their findings.

Although the right to be granted DP is related to the individual’s work history, there are only a small number of studies (24–29) that have investigated the association between occupation and risk of DP. These studies have either investigated specific occupational groups (24–26), and/or have not taken DP diagnoses into account (27–29). To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies of the association between occupation and risk of DP due to mental diagnoses have been published.

In observational studies, it is essential to account for potential confounding (30). Previous studies have established that female sex, older age, being unmarried, having children, lower socioeconomic status, and various regional locations are associated with DP, in general and also due to mental diagnoses (7, 31–33). Hence, it seems important to account for these covariates in analyses of work-related risk factors for DP.

Moreover, both mental disorders (34–36) and DP due to mental diagnoses (37, 38) have been shown to be moderately heritable in earlier studies. However, whether choice of occupation and, hence, type of working conditions are heritable or not has so far not been studied. Still it may be possible that genetics and shared environmental factors (familial factors) may confound the associations between occupational status, working conditions, and DP due to mental diagnoses. Familial factors can be controlled for by studying twin pairs who, in this case, are discordant for DP and occupation or psychosocial working conditions. This means that the twin pairs are matched for familial factors but differ in exposures (for example psychosocial working conditions). Furthermore, it would be possible to clarify the underlying pathways in the associations if they differed in whether or not they had DP [see (39) for details of the study design]. If the familial factors are important, then an association of the whole cohort will be substantially different from the results of the discordant twin-pair analyses. Conversely, if the analyses of discordant twin pairs are similar to the associations of the whole cohort, then one can assume that factors specific to each individual are more important. Only a handful of studies have used twin data in studies of DP (32, 33, 40–43), but none of these has studied psychosocial working conditions or occupational groups as risk factors for DP due to mental diagnoses. Occupational affiliation has, however, been employed as a basis for establishing socioeconomic status in some of the earlier studies (32, 41, 42).

This study had two aims: to (i) study prospective associations between psychosocial working conditions, measured using a validated JEM, and occupational grouping and the risk of being granted DP due to mental diagnoses; and (ii) evaluate the influence of familial factors on these associations.

Methods

Study design and population and register linkages/data collection

This study is based on data from a prospective twin cohort, the Swedish Twin Study of Disability Pension and Sickness Absence (STODS), which includes all twins born 1925–1958 in Sweden (N=59 893) (44). The twins were identified in the Swedish Twin Registry (45), which provided information on date of birth, sex, pair identification, and zygosity. Included in this study were twins who, on 1 January 1993, were alive, living in Sweden, <65 years old, not on old-age pension or DP in December 1992, and registered as working in November 1990. The final study population (twins born between 1928–1958) constituted 42 715 individuals; of which 17 281 were complete twin pairs [4154 monozygotic (MZ), 6072 same-sex dizygotic (DZ); 6214 opposite-sex DZ, and 841 with unknown zygosity], and 8153 single individuals. For the latter group, information on the co-twin was missing due to death, emigration, DP, early old age pension, or not registered as working in 1990. The twins were 32–62 (mean 45) years of age in 1990. During follow-up, the twin individuals delivered person time in days up until death, emigration, reaching 65 years of age, old-age pension, DP, or end of follow-up (31 December 2008).

Data on DP, including date and diagnosis, were obtained from the Swedish Social Insurance Agency (44). Date of death was obtained from the Causes of Death Registry. All other data were obtained from Statistics Sweden. The Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm approved the study (2007/524-31).

Disability pension

For this study, the outcome of concern was defined as being granted DP due to mental diagnoses during follow-up 1993–2008. Mental diagnoses were encoded using the 9th and 10th revisions of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) (46), with translation of the ICD-9 codes into ICD-10 (F00-F99). Information about DP diagnosis was missing in 1% of the DP cases.

Occupation and psychosocial working conditions

Occupations were encoded according to the Nordic Standard of Occupational Classification (NYK, version 1985), encompassing a total of 320 occupational 3-digit codes (21). We used these codes to effect a categorization into eight different sector-based occupational groups, namely: technology, science, social science, and art (NYK-codes 000–099); healthcare and social work (NYK-codes 100–199); administration and management (NYK-codes 200-299) [reference group (27, 29)]; commercial work (NYK-codes 300–399); agriculture forestry, and fishing (NYK-codes 400–499); transport (NYK-codes 600–699); production and mining (NYK-codes 500–599 and 700–899); and service and military work (NYK-codes 900-989).

Psychosocial working conditions were assessed on the basis of the Job Demand-Control-Support model (8–10) and measured by applying a validated JEM, which is based on data from the Swedish Work Environment Survey 1989–1997 (N=48 894), to the 320 occupational codes (20–22). Each twin in the cohort was assigned a separate mean score (range 0–10), based on occupation, sex, and age for job demands and control and social support, respectively. These mean scores were then used as continuous variables in the analyses. For each of the dimensions, higher scores meant more favorable characteristics (low demands, high control, and high support), while lower scores indicated the opposite. For descriptive purposes, the mean scores of each working conditions were split into quartiles and medians (47, 48). To measure type of jobs, the medians of job demands and job control were combined (47) into a 2 × 2 table with four categories: (i) high strain (high demands, low control), (ii) low strain (low demands, high control) (reference group), (iii) active (high demands, high control), and (iv) passive (low demands, low control). In addition to the above categories, a fifth category was defined by adding the dimension of low social support to high strain: iso strain.

The following covariates were included in the analyses of the whole twin cohort with psychosocial working conditions and occupational groups in relation to DP due to mental diagnoses: sex (with men as reference group), age (birth year), education (number of years of study), marital status [married (reference group) versus non-married], children living at home [no children living at home versus children living at home (reference group)], and type of living area [urban/semi-urban area (reference group) versus semi-rural/rural area) (49).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated, and hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were estimated using Cox proportional hazards regression models for the twins in the whole cohort. The underlying timescale started at point of inclusion in the study, and time was measured in days. The proportional hazards assumption was tested by examining the log-log curves for each categorical factor, and all the curves were found to be acceptably parallel. To account for the influence of within-pair dependency on standard errors, the analyses were clustered on pair identity. Different strategies for censoring were adopted, but since there were minor differences between the strategies, we present here only the results of analysis censoring for no DP and other DP diagnoses. The HR were calculated for men and women separately, but since there were no major differences between the sexes based on similarity of HR and overlapping CI, we combined men and women in the further analyses although we adjusted all analyses for sex. The Cox models were first adjusted for sex and age (base model) and then for all the covariates (full model). Furthermore, to investigate the potential effect of psychosocial working conditions on the association between occupational groups and DP we included the continuous variables of psychosocial working conditions in the full model of occupational groups. Finally, interactions between job demands and control and social support were tested in models without other covariates. The statistical significance of the interaction terms was tested by the log-likelihood ratio test.

Thereafter, discordant twin pair analyses were performed using conditional Cox proportional hazards regression models, including only complete MZ and same-sex DZ twin pairs. The conditional Cox analyses were stratified by pair identity, allowing each twin pair their own baseline hazard; hence, the time to DP was studied in relation to the corresponding follow-up time for the co-twin. Only those twin pairs discordant on both DP and exposure contributed information to these analyses. First, we ran the analyses for MZ and DZ together to see whether there was any influence of familial factors on the associations between DP and (i) psychosocial working conditions and (ii) occupational groups. If the associations from the whole cohort, for example, attenuated or changed direction in the discordant twin pair analyses, it would suggest the presence of familial confounding, mainly from shared early environmental factors (50). Second, we ran the analyses stratified by zygosity. If an association from the whole cohort was found to be weaker but still remained among discordant DZ twin pairs, and is to a larger extent attenuated for MZ twin pairs, this would indicate the presence of genetic confounding (50). However, since there were no major differences between MZ and DZ twins, based on similarity of HR and overlapping CI, we decided to present the results for all twins together. The number of discordant twin pairs for DP due to mental diagnoses were 188 for MZ pairs and 323 for DZ pairs. All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS version 20 (SPSS Institute, Chicago, IL, USA) and STATA version 11 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

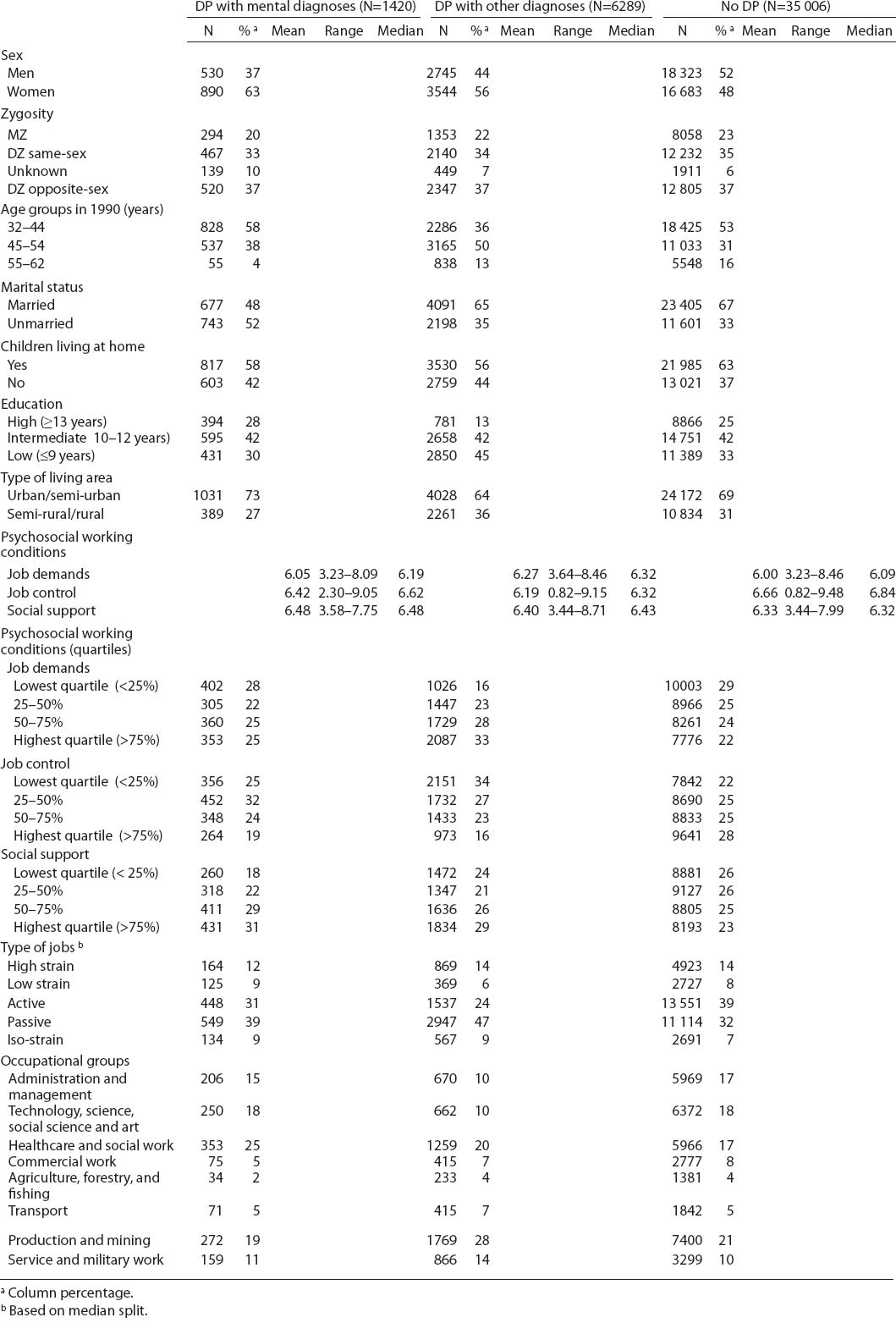

In total, the twin individuals delivered 1.92 million person-days at risk of DP during follow-up from 1993–2008. The mean follow-up time was 12 years, and 7709 individuals (18%) were granted DP during follow-up. Of all DP, 1420 (18%) were due to mental diagnoses. Depression (F30-F39) and anxiety (F40-F48) diagnoses constituted 74% of the mental diagnoses, and schizophrenia (F20-29) (8%) and substance abuse (F10-F11) (7%) were the next largest diagnostic groups. More women than men were granted DP due to a mental diagnosis (63%), and mean age at DP due to mental diagnosis was 56 [standard deviation (SD) 6.0] years (table 1).

Table 1

Descriptives for covariates and exposures in the cohort, specified for individuals granted disability pension (DP) with mental diagnosls, DP with other diagnoses, and had no DP during follow-up 1993–2008 (N=42 715). [MZ= monozygotic; DZ= dizygotic]

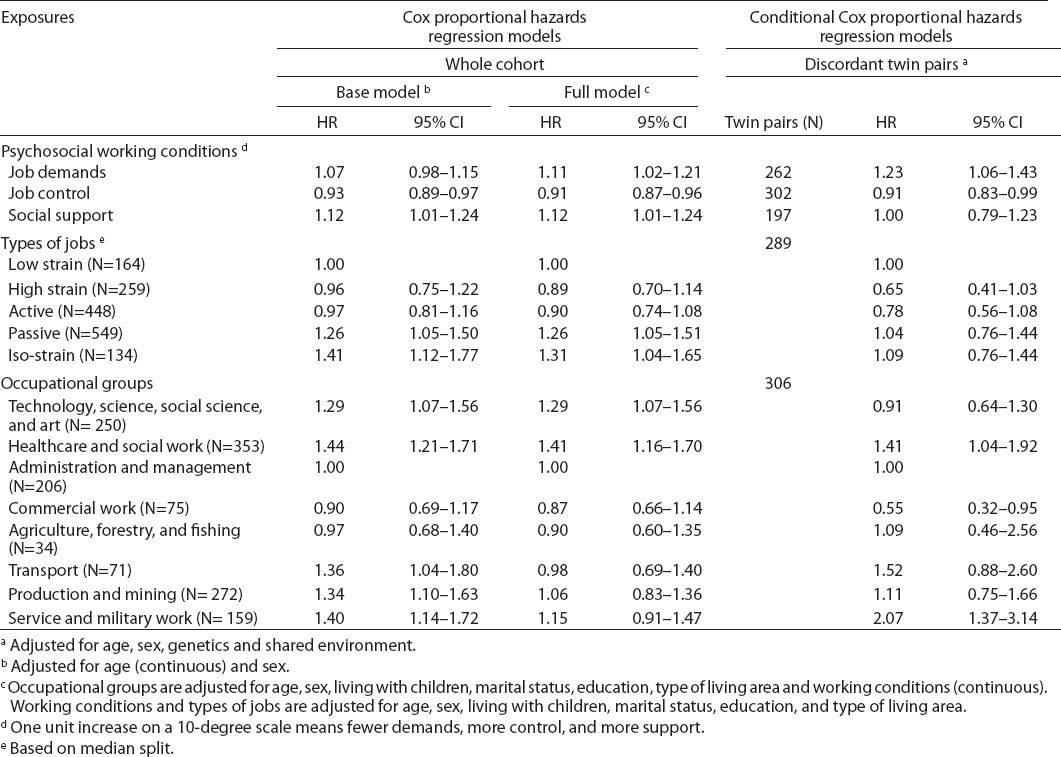

Psychosocial working conditions

In the base models, each one unit increase in social support (HR 1.12, 95% CI 1.01–1.24) was significantly associated with an increased risk of DP due to mental diagnoses, while each one unit increase in job control (HR 0.91, 95% CI 0.87–0.96) was associated with a decrease in DP of this kind during follow-up (table 2). These associations remained after further adjusting for education, marital status, children living at home, and type of living area. Furthermore, in these fully adjusted models, job demands became statistically significantly associated with DP (HR 1.11, 95% CI 1.02–1.22). In the discordant twin pair analyses, the associations of job demands and control with DP remained and even became more strengthened for job demands, while the association of social support with DP was attenuated, becoming non-significant.

Table 2

Associations of psychosocial working conditions, and occupational groups, with disability pension (DP) due to mental diagnoses for the total cohort (N=42 715), and discordant twin pairs (N=511) during follow-up 1993-2008. [HR= hazard ratio; 95 % CI= 95% confidence interval]

In the models including interactions between the three dimensions of working conditions, job demands × social support (P<0.05) and job control × social support (P<0.001) turned out to be statistically significant.

Having a job characterized as passive (HR 1.26, 95% CI 1.05–1.50) or iso-strained (HR 1.41, 95% CI 1.12–1.77), compared with a job characterized as low strain, was associated with increased risk of DP due to mental diagnoses (after accounting for age and sex in the models). These associations were attenuated somewhat in the fully adjusted models and were non-significant in the discordant twin pair analyses.

Occupational groups

In the base models, all the sector-based occupational groups, with the exceptions of commercial work and agriculture, forestry, and fishing, were associated with DP due to mental diagnoses (table 2). After accounting for education, marital status, children living at home, type of living area, and psychosocial working conditions, only the occupational groups healthcare and social work (HR 1.41, 95% CI 1.17–1.70) and technology, science, social science, and art (HR 1.29, 95% CI 1.06–1.57) were still associated with DP. In the discordant twin pair analyses, the associations of the occupational groups healthcare and social work and service and military work with DP remained, while the occupational group commercial work became statistically significantly associated with a lower risk of DP (HR 0.55, 95% CI 0.32–0.95).

Discussion

This study of a large population-based cohort of twins adds to already-existing knowledge, based on unrelated individuals, of psychosocial working conditions and sector-based occupational groups as potential risk factors for DP due to mental diagnoses. On the one hand, we found that each one unit increase in job demands or control and having a job in either healthcare and social, service and military, or commercial work were independent predictors of DP due to mental diagnoses. On the other hand, we found that familial factors seem to influence the associations between DP and (i) each unit increase in social support and type of jobs and (ii) the occupational groups technology, science, social science, and art and production and mining.

Our finding that a one unit increase in job control was independently associated with a decreased risk of DP due to mental diagnoses confirms earlier studies (11–19, 51). However, the results that each one unit increase, rather than a decrease, in job demands or social support predict a higher risk of DP contradict those of previous findings (13, 17, 31, 52). Nevertheless, only the association of job demands with DP seems to be direct; hence not influenced by factors shared by the twins, such as family social background or norms or values of the family. One explanation for these contradictory results may be the application of a validated JEM (20–22), while the majority of other studies (11, 15–19) used individually reported data on experiences of such exposures. Also, previous studies have mainly studied these working conditions as categorical (median split, quartiles) rather than as continuous variables and have, therefore, only been able to capture variation within the different categories (11, 15–19, 47). Another explanation is that since the information about psychosocial working conditions was based on sector-based occupations, adjusting for occupation to account for the influence of socioeconomic status was not possible. Instead, we used education as a proxy for socioeconomic status in the models.

When it comes to types of jobs, our findings both confirm and contradict those of previous studies. In line with two recent Belgian studies (15, 53), we found that, among all twins in the cohort, having a passive or iso-strain job predicted higher risks of DP due to mental diagnoses than a low-strain job. However, these associations disappeared after accounting for the influence of familial factors. This would be a sign that factors shared by the twins, for instance family socioeconomic status, are of importance for those associations. In contrast with a recent Finnish study (54), which also applied a JEM to the data and found an association between high job strain and DP due to depression among women (HR 1.24, 95% CI 1.00–1.53), there was no such association in our study. This contrast may be due to differences in study designs and participants; that is, the Finnish study was based on municipal workers with shorter follow-up time (five years), only included one mental diagnosis (ie, depression), and did not take account of familial confounding.

In line with two other studies (28, 29), we found that working in healthcare and social work or service and military work were independent risk factors of being granted DP due to mental diagnoses, even after accounting for potential familial confounding, for instance shared social background. One possible explanation for these findings is that these occupational groups are numerically female dominated, and working in a female-dominated sector has been found to be a risk factor for sickness absence with a mental diagnosis (55, 56). Also, these two sector-based occupational groups included occupations (ie, nurses and cleaners) that are known to be associated with mentally and/or physically challenging working conditions including low control and uncomfortable working positions and/or heavy lifting (57–60). Commercial work became significantly associated with DP due to mental diagnoses after accounting for familial factors, suggesting that engaging in such work is an independent protective factor of such DP. However, in the associations between DP and the occupational groups technology, science, social science, and art and production and mining there may be some familial confounding, suggesting selection (eg, by social background) into these occupational groups. Finally, the association between the transport work and DP was mainly related to other background factors from adulthood, including education, marital status, and psychosocial working conditions rather than familial factors. In future studies, more precisely determined occupational groups and a larger cohort would further clarify these associations and any influential factors.

Strengths and limitations

The main strengths of this study are the large sample (N=42 715), the long follow-up (mean 12 years), the use of twin data that made it possible to account for potential familial confounding, the prospective cohort design, and the use of high-quality, population-based registry data with no loss to follow-up. A further strength is access to information on diagnosis-specific DP, which is not common. Moreover, we accounted for the influence of several known risk factors for DP in the analyses (31–33, 51). The inclusion of information about children living at home, marital status, education, and type of living area in the models resulted in almost unaltered risk estimates for the association between psychosocial working conditions and DP due to mental diagnoses. This suggests that these associations are independent of these background factors. However, further adjusting the full model with occupational groups for psychosocial working conditions attenuated some of the associations found between occupational groups and DP. We also used a JEM to obtain more comprehensive information on job demands and control and social support. By applying occupation-rated mean scores of working conditions, we were able to avoid reporting bias related with health (3). Furthermore, the matrix has been validated by correlating attributed scores with self-reported equivalents for the separate working conditions and by comparing attributed and self-reported scores on several health outcomes (back pain, sleep disturbance, and mortality). The agreements were found to be moderate for job control and somewhat lower for job demands and social support (20). This might partially explain the differing result of this study regarding job demands and social support. Nevertheless, since this is the first time this matrix is used in studying DP due to mental diagnoses, more studies are needed to confirm the findings of this study.

Partially related to the JEM, a limitation of the study is the coding of occupational groups. In the Nordic Standard Occupational Classification system, similar occupations are grouped together without consideration of individual differences, such as educational level, or employment status (whether employed or self-employed, or short-term or permanent position). Hence, some occupational groups may, at the same time, be exposed to both harmless and/or hazardous occupational exposures (28). Nevertheless, we believe that some of these differences were addressed by adjusting for years of education. It is well known that highly educated people work in occupations with, for instance, better working conditions, and salary levels compared to individuals with lower education (61). A second important limitation is that we had no baseline information regarding morbidity or health status. Thus, the results may be biased by unmeasured confounding from ill-health (12). However, two recent observational studies of associations between self-rated health, social class, and future DP (62, 63) found only weak contributions of ill-health and/or health behavior for these associations. A third limitation is that information on occupation, including working conditions, was only available at baseline: we were, therefore, unable to account for changes during follow-up. Fourth, despite the large sample size, we lacked power in the discordant twin pair analyses. Hence the interpretations of these analyses merit caution.

Concluding remarks

In this study, it was found that one unit increase in the psychosocial working condition job demands and working in either healthcare and social work or service and military work appear to be risk factors of DP due to mental diagnoses, independent of age, sex, marital status, having children, educational level, type of living area, working conditions, or familial factors. One unit increase in the psychosocial working condition job control or being employed in commercial work, however, seem to be direct protective factors of such DP, even after accounting for various background factors and familial confounding. Nevertheless, there also seems to be some complexity in the associations between psychosocial working conditions, occupational groups, and DP since not all were independent of the effect of familial confounding. Hence, it may be assumed that there are some prerequisites related to familial factors that may influence the associations of DP due to mental diagnoses with some of the psychosocial working conditions and occupational groups.