Workplace health promotion has the potential to decrease cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk (1–3) and has shown positive, but small, effects on productivity at work, sickness absence, and work ability (4). A systematic review demonstrated that the effectiveness of a workplace health-promotion program depends on the study population, the intervention content, and the methodologic quality of a study (4). However, little is known regarding the influence of the quality of implementation on the effectiveness.

Several studies have reported serious problems with the actual implementation of workplace health promotion. Recurring problems are low participation (5), high attrition (6), and large diversity in the quantity and quality of the delivered intervention (7). A thorough evaluation of the quality of implementation alongside an effect evaluation is recommended (1, 8–10), enabling optimization of the intervention for increasing effectiveness and broader implementation across settings.

The PerfectFit intervention study investigated motivational interviewing (MI) supplementing a web-based health risk assessment (HRA) among older workers (≥40 years) with an increased CVD risk, a so-called “blended care” approach (11). The HRA included tailored and personalized feedback based on the participant’s risk profile. MI allows a more patient-centered approach, focusing both on specific behavior changes and the most preferred action by the individual (12). A limited intervention group received solely the web-based HRA. Within the framework of this cluster randomized controlled trial (cluster RCT), a detailed evaluation of both participation in health promotion activities and the implementation was possible.

So far, literature on the required number of MI sessions and the duration of MI has been indecisive (13). A previous study showed that a higher frequency of MI sessions was associated with a more advanced stage of change in individuals at increased risk for CVD (14). Several reviews suggest that MI quality, ie, compliance to MI principles, is an important factor in the management of health behavior such as weight loss (15), physical activity (16), or alcohol consumption (17). Nonetheless, MI quality appears to be either rarely measured (18) or is not investigated in relation to primary health behavior outcomes. High empathy and MI adherent behavior were suggested to be predictive for behavior change in addiction treatment (19–21), but none of the MI elements were previously related to any health outcome in a randomized setting. This lack of insight in the working mechanism of MI hampers optimization of intervention delivery and effectiveness.

Therefore, the current study addressed the quality of implementation and its influence on health behavior. The PerfectFit study objectively measured components of quality of implementation, ie, reach, quantity of implementation, and quality of MI, as well as the effects on participation in health-promotion activities. The aims of the current study were to (i) determine the quality of implementation of a workplace health promotion intervention and (ii) evaluate its influence on employees’ participation in health promotion activities.

Methods

Design

An extensive description of the PerfectFit study design was previously published (11). In this multicenter cluster RCT, 18 military bases, regional police forces, and hospital wards within the Netherlands were equally randomized as “clusters” to the intervention and control arm of the study. As determined by law, all employees of these organizations have unlimited access to the occupational health center. Individuals from participating units were allocated by the occupational physician (OP) based on having at least one risk factor for CVD at the cardiovascular risk profiling, the so-called “cardio-screening”. The trial consisted of two intervention groups: (i) the limited intervention group, which received a tailored and web-based HRA with personalized feedback, and (ii) the extensive intervention group, which additionally received counselling sessions from the OP using MI. Follow-up measures were taken by online questionnaires at 6 and 12 months after baseline, and a cardio-screening was conducted at the health center at 12 months. Participation in health-promotion activities was measured, since this is positively related to health behaviors (22). A standardized form with results of each MI session and cardio-screening was sent to the principal investigator (PI). The CONSORT extension for cluster trials was used to report on performance of the study (23) (see supplementary table S1, www.sjweh.fi/show_abstract.php?abstract_id=3716).

A PerfectFit flyer was custom made for each organization. The flyer was handed to employees during the cardio-screening. Only military employees were mandated to attend this screening every three years. Information on PerfectFit was also published on the intranet and sent in a memo to managers of each cluster. Participation in the study was voluntary and free of charge. The initiation of recruitment differed between clusters and started between 2012 and 2014. Follow-up was completed by September 2015.

The Medical Ethics Committee of Erasmus MC Rotterdam (METC) approved the study (MEC-2012-459). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after they were found eligible at the cardio-screening and the OP had informed them about all aspects of the study. The study was registered in the Netherlands Trial Registry (NTR4894). Additional approval was obtained for participation of hospital wards.

Sample

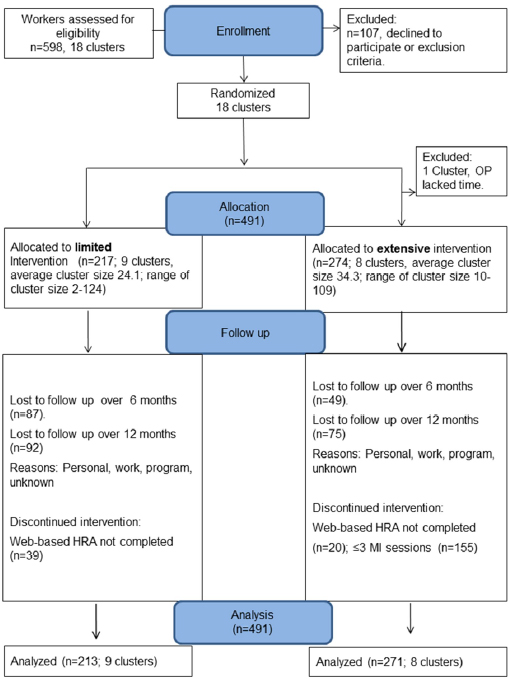

One cluster dropped out prior to any inclusion of employees due to conflicting OP work commitments so analyses were conducted for 17 clusters of employees. The target population consisted of employees aged ≥40 years at increased CVD risk, either working in the military, for the police force, or at an academic hospital. Prior calculations estimated eligibility of 5444 employees. A total of 652 individuals (12%) were screened, of whom 598 (91.7%) had ≥1 CVD risk factor, and 491 (82.1%) could be included in the study based on having ≥1 CVD risk factor (ie, smoking, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, physical inactivity, or CVD in a first-degree relative) and having no exclusion criteria, ie, manifest CVD, a terminal illness, or a history of psychosis. Screening took place at the in-company occupational health centers.

Intervention

The extensive intervention consisted of three face-to-face and four telephone sessions with an OP, in addition to a web-based HRA that was administered in both intervention groups. Counseling was performed using the principles for MI and focused on the personal medical profile and preferences for change of each individual, in order to achieve long-term healthy behavior. An online newsletter with general information on PerfectFit and healthy ageing, including a section on motivational aspects (only for the extensive group), was sent every three months to all participants and OP.

A total of 21 OP (57.1% male) performed both interventions, including one general practitioner (military), and had been employed for 11.9 years on average (range six months to 45 years). Prior to any inclusions, 10 OP were assigned to the extensive intervention and received three full days of training by a certified trainer. During the intervention period, they additionally received three follow-up coaching sessions of four hours each. The PI taught these sessions and was trained by the same trainer with an extra three days module on scoring MI according to the MI treatment integrity (MITI) method, version 3.1.1 (24). For the hospital, the OP performed the first MI sessions, while a lifestyle coach with extensive experience in using MI conducted the follow-up MI sessions.

Measures

Quality measures were components of intervention implementation, ie, reach of web-based HRA, participation in HRA, reading newsletters, and number and quality of MI sessions. Effect measure was participation in health-promotion activities.

Quality of intervention implementation

Reach was determined at individual level and defined as “the number of individuals allocated after cardio-screening and to whom HRA was offered” (table 1). Based on other studies, it was expected that 57% of the individuals would meet the eligibility criteria (25). Enrollment, and allocation of individuals were based on the baseline cardio-screening profiles.

Table 1

Quality of intervention implementation [HRA=health risk assessment; MI=motivational interviewing; MITI=MI treatment integrity; OP=occupational physician; SD=standard deviation.]

| Components | Measurements | Levels | Data sources | N | % | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reach of web-based HRA | Number allocated after cardio-screening and to whom HRA was offered: | Individual | Consent forms | 491 | 82.4 | ||

| Limited intervention group | 217 | 44.2 | |||||

| Extensive intervention group | 274 | 55.8 | |||||

| Quantity of the intervention a | MI sessions received: | ||||||

| Total consultation length (minutes) | Individual | MI forms | 103.9 | 64.8 | |||

| Face-to-face sessions | 2.5 | 1.6 | |||||

| Telephone sessions | 1.5 | 1.5 | |||||

| ≥4 MI sessions | 155 | 56.5 | |||||

| Quality of MI a MI fidelity | Behavior counts: | ||||||

| Open questions | OP | MITI scoring of audiofragments | 40.7 | 13.1 | |||

| Reflections versus questions | 118 | 60 | |||||

| Complex reflections | 69.0 | 13.2 | |||||

| MI adherent statements | 83.7 | 10.3 | |||||

| Global scores: | |||||||

| Empathy (1–5) | OP | MITI scoring of audiofragments | 3.5 | 0.5 | |||

| Direction (1–5) | 4.4 | 0.5 | |||||

| MI spirit (1–5) | 3.6 | 0.5 | |||||

| Mean global (1–5) | 3.8 | 0.4 |

Quantity aspects of the intervention were assessed on three intervention components: (i) Web-based HRA. The OP personally handed all included participants an invitational letter to login and complete a web-based HRA. The HRA was considered completed if a personalized report including suggestions of choice of health-promotion activities was generated, which meant that the participant logged on to the system, registered, and completed all items of the HRA. (ii) Newsletters read: The proportion of participants who read the online newsletters was measured electronically by at least opening the newsletters (26). (iii) MI sessions: Information on the type of contact (face-to-face or by phone) and the duration of the session was retrieved from the MI forms sent by OP to the PI after each session.

To evaluate the overall quality of MI, aggregated scores of 35 double-coded audio-recorded MI sessions were used, ranging from 1–4 recordings per OP. The OP and the lifestyle coach in the extensive group were asked to record the first session of every third month and send this to the PI. The entire sessions were transcribed verbatim and coded independently by two coders (the PI and a co-investigator) using the validated MITI version 3.1.1 (24). Both coders are experienced in MI coaching and coding. To avoid inter-coder interpretation differences, the coders discussed their respective ratings of three recordings (19).

After every three months, each OP was asked to audio record the first face-to-face consultation with a participant, using a voice recorder. Of the 38 recordings received, 3 were excluded due to technical problems. Coding focused on behavior counts and global scores, both considered core-elements of MI.

Behavior counts were based on the assignment of every OP’s utterance to one of three primary behavior codes: (i) MI statements; (ii) questions; and (iii) reflections. Within these categories, a sub-classification was made into adherence to MI (yes/no), open or closed question, and simple or complex reflection. Summary scores on behavior counts were calculated presenting the percentage open questions, complex reflections, MI adherence, and a reflection-to-question ratio. Global scores were given on a five-point Likert scale, with a higher score indicating better MI skills. Five global dimensions were rated: evocation, collaboration, autonomy/support, direction, and empathy. Calculated summary scores present “MI spirit” (evocation + collaboration + autonomy/support), and a mean global score (global dimensions / 5). The interrater-reliability (IRR) between coders of summary scores was fair to excellent (IRR range 0.51–0.75) (19), except for the global scores “empathy”, “spirit”, and “mean global” (IRR<0.40, classified as poor) (see supplementary table S2, add www.sjweh.fi/show_abstract.php?abstract_id=3716). Therefore, consistent with Jelsma et al (19), we did not restrict our analyses to one coder, but calculated mean scores of both coders, and used these in further analyses.

According to the MITI code, a clinician’s competence level can be classified as beginner’s or advanced level based on: percentage open questions (≥50% or ≥70%), percentage complex reflections (≥40% or ≥50%), percentage MI adherent (≥90% or ≥100%), reflection to question ratio (≥1 or ≥2), and a mean global score (≥3.5 or ≥4).

Effect measure

Participation in health-promotion activities

Self-reported participation in health-promotion activities was asked after 6 and 12 months: “In the past 6 months, did you start a health-promotion activity, such as…”. Answering options were: take up physical activity, improve diet, quit smoking, reduce alcohol consumption, reduce stress, improve working situation, participate in other health promotion activities, or no participation. For our analyses, “reducing stress” and “improving work situation” were combined into one category, because of low frequencies. Participation in “at least one health promotion activity”, was considered positive if at least one answering option was ticked, with the exception of “no participation”.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to generate frequencies and percentages for dichotomous and categorical variables and means and standard deviations for continuous variables. To test the differences between groups, Chi-Square tests and ANOVA-tests were performed.

The effects of the intervention after 6 and 12 months on the uptake of health promotion activities was evaluated using mixed-effects models with the intervention as fixed effect. All mixed-effects models were adjusted for cluster, gender, age and education, and included the baseline value of the measure of interest. The intra-cluster correlation values to evaluate the within cluster variation were 0.08 at the highest, implying that the clustering had little effect on the results. An additional analysis was conducted to assess whether quantity and quality of MI were associated with at least one health promotion activity during the trial period. MI quality was measured and calculated per OP and assigned to each participant in the according cluster. Thus, analyses on MI quality were done on 274 individuals in the extensive intervention group.

Inter-rater reliability scores were calculated by intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC), using a two-way mixed model with absolute agreement (see supplementary table S2). Since these were neither good nor excellent according to the benchmark values (19) (ICC empathy 0.28-95% CI -0.05–0.56 and MI adherence 0.51; 95% CI 0.22–0.72), aggregated scores of both coders were used in the analyses.

Missing values were imputed five times using multiple imputation and results from the imputed datasets were pooled using Rubin rules. Data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics version 21 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). For the mixed-effects model, we used the R package lme4.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the study population were described in a previous publication (11). The mean age was 52 years, 81% were male, and 78% was medium or highly educated. Figure 1 shows a total of 491 individuals (18 clusters) who were included, of whom 217 (within 9 clusters) were allocated to the limited intervention and 274 (within 8 clusters) to the extensive intervention group. Response to follow-up questionnaires was 355 (72.3%) at 6 months and 324 (66.0%) at 12 months.

Table 1 provides an overview of the components of implementation. The overall uptake of the cardio-screening was 12% (652 out of 5444 potentially eligible, not shown). Based on the cardio-screening, 92% (598) was eligible to participate in the study. Of those who were eligible, 82% (491) could be allocated to either intervention-group (“Reach”). Once included in the study, 88% fully completed the HRA, on average 60% (range 55–67) of the newsletters was read, and on average four MI sessions were attended (extensive group only) (see supplementary table S3, add www.sjweh.fi/show_abstract.php?abstract_id=3716). At least four MI sessions were attended by 155 (56.5%) participants.

Supplementary table S3 shows differences between organizations in all components of the implementation. The uptake of cardio-screening differed between organizations: military 12%, police 13%, and hospital 34% (not shown), as well as the numbers of employees allocated to the study, from 71% for the military to 90% for police and hospital. Newsletters were read most frequently in the police force. At least four MI sessions were received by 15% in the hospital, 51% in the military, and by 73% of the police force. MI was performed at least at beginner’s level of competence for all scored items, except for open questions and MI statements. MI quality differed between OPs and between organizations. Analyses of variances on the behavior counts in the evaluation of the quality of MI delivered showed up to 66% of the variance originated within OPs, which could not be explained by changes over time (data not shown). Analyses of variances in global scores showed the variance originated up to 44% within OPs, and up to 56% between OPs.

Table 2 presents 8% higher participation in health-promotion activities (≥1 activity) in the extensive compared to the limited intervention group, at both 6 months and 12 months follow-up. In total, >80% participated in ≥1 health activity. The extensive group showed 13.8% more participation in improving diet activities (statistically significant), and 9.5% more in physical activities than the limited group at 12 months, albeit non-significant. In addition, they showed a near significant higher participation in activities for smoking cessation (4.2%) and other activities (3%), and no differences in stress-reduction activities, in the extensive compared to the limited group.

Table 2

Participation in health-promotion activities at follow-up, with sub-analysis on the activity of choice.

| Participation in health- promotion activities a | Limited intervention | Extensive intervention | Estimated effect (difference) b,c | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| 6 months | 12 months | 6 months | 12 months | 6 months | 12 months | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | |

| ≥1 health-promotion activity | 112 | 86.2 | 104 | 83.2 | 213 | 94.7 | 181 | 91.0 | 8.3 | -1.4–14.4 | 8.2 | -4.1–17.6 |

| More physical activity | 95 | 73.1 | 89 | 71.2 | 176 | 78.2 | 165 | 82.9 | 0.8 | -10.2–9.3 | 9.5 | -6.7–15.6 |

| Improve diet | 61 | 46.9 | 67 | 53.6 | 142 | 63.1 | 137 | 68.8 | 13.5 d | 0.1–28.4 | 13.8 d | 0.5–25.7 |

| Smoking cessation | 6 | 4.6 | 3 | 2.4 | 14 | 6.2 | 14 | 7.0 | -0.4 | -6.5–3.9 | 4.2 | -0.1–8.6 |

| Reduce alcohol intake | 17 | 13.1 | 18 | 14.4 | 37 | 16.4 | 31 | 15.6 | 2.2 | -10.0–7.9 | 2.0 | -10.7–8.8 |

| Reduce (work) stress | 31 | 23.8 | 23 | 18.4 | 55 | 24.4 | 40 | 20.1 | -1.9 | -13.7–5.6 | 0.0 | -5.6–14.3 |

| Other health-promotion activity | 7 | 5.4 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 4.4 | 4 | 2.0 | -1.0 | -2.0–1.0 | 3.0 | 0.0–3.4 |

b Adjusted for age, gender, level of education, clustering, and also adjusted for baseline health risk behavior.

Table 3 displays the association between quantity and quality of MI and participation in health promotion activities. A longer duration of MI (OR 1.01, 95% CI 1.00–1.03) was associated with increased participation in health activities after 6 months, explaining more participation in activities by the police than other organizations. However, the strength of this association was absent after 12 months (OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.99–1.01). More open questions in the MI sessions was associated with increased participation in activities (OR 1.60, 95% CI 1.00–2.20), which remained after 12 months, albeit non-significant. For all global scores on quality of motivational interviewing a positive, but in general not statistically significant, association with participation in activities was found. The rating of “Direction” was most strongly associated with participation, especially after 12 months (OR 3.25, 95% CI 1.07–9.88).

Table 3

The association between motivational interviewing (MI) and participation in ≥1 health-promotion activity at follow-up. [CI=confidence interval; OR=odds ratio; Ref=reference group]

| 6 months N=225 (82.1%) | 12 months N=199(72.6%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| ORa,b | 95% CI | ORa,b | 95% CI | |

| Organization | ||||

| Hospital | Ref | Ref | ||

| Military | 7.63 | 0.96–8.65 | 2.56 | 0.45–2.05 |

| Police | 1.61d | 1.42–13.54 | 0.43 | 0.54–3.15 |

| MI intervention characteristics c | ||||

| Quantity of MI sessions | ||||

| Consultation length (mins) | 1.01d | 1.00–1.03 | 1.00 | 0.99–1.01 |

| Face-to-face sessions | 1.58 | 0.92–2.71 | 0.91 | 0.60–1.38 |

| Telephone sessions | 1.38 | 0.80–2.39 | 0.91 | 0.62–1.32 |

| ≥4 MI sessions | 1.58 | 0.92–2.71 | 0.90 | 0.60–1.37 |

| Quality of MI | ||||

| Behavior counts | ||||

| Open questions (per 10%) | 1.60d | 1.00–2.20 | 1.50d | 1.00–2.00 |

| Reflections versus questions | 0.45 | 0.15–1.30 | 0.66 | 0.26–1.65 |

| Complex reflections (%) | 1.02 | 0.97–1.08 | 1.02 | 0.98–1.06 |

| MI adherent statements (%) | 0.99 | 0.92–1.08 | 1.00 | 0.94–1.06 |

| Global scores | ||||

| Empathy (1–5) | 1.48 | 0.35–6.16 | 1.59 | 0.49–5.22 |

| Direction (1–5) | 2.34 | 0.56–9.80 | 3.25d | 1.07–9.88 |

| MI spirit (1–5) | 1.84 | 0.42–8.00 | 2.24 | 0.76–6.56 |

| Mean global (1–5) | 2.04 | 0.38–10.87 | 2.54 | 0.75–8.57 |

Discussion

The reach of the intervention was limited, but the majority of initial participants completed the HRA and opened the newsletters regularly. There were large differences in the quality of the implementation between the participating organizations. A higher quantity and quality of MI was related to more participation in activities, and this effect sustained with a higher MI quality. Over 80% of the participants participated in health promotion activities, with an additional 8% in the extensive intervention group at short and long-term follow-up, compared to the limited group.

Low overall uptake of the cardio-screening may be due to personal internal factors (perceived relevance and readiness to face screening outcomes) (27, 28). Differences in reach between organizations are likely to be due to organizational factors, such as (i) concurrent reorganizations from regional into national forces (police), and cut downs (military), with insecurities about job positions; (ii) lack of commitment for the cardio-screening by the management (military); and (iii) more active role by human resources in health communication (hospital). A low grade of participation in the study by the military compared to the other organizations may be due to soldiers leaving for missions abroad. In future implementation, optimizing communication and the organizational context would enable more people to benefit.

Although the HRA completion and newsletter reading were high, just 25% of the individuals received all seven protocoled MI sessions. The participation in the HRA (88%) was much higher than the reported average of 32% in other studies (29). Potential explanations are that participants with ≥1 CVD risk factors were asked to participate (29), and the baseline cardio-screening acted as informed decision-making, and thus created a feeling of personal relevance (30). Receiving the number of MI sessions according to the protocol appeared more difficult in the hospital than other organizations. It could be speculated that either physical fitness is more important to individuals who work in the military and police force due to a selection bias in job requirements or that hospital employees are hesitant to visit a lifestyle coach instead of an OP. Overall, 43% attended less than four MI sessions, which may have been due to busy OP calendars and workers’ time conflicts or to perceived less added value of multiple sessions by OP or workers. In line with Burkirk’s review (31), who found as few as one MI session to be effective in enhancing readiness to change and action directed towards reaching health behavior-change goals, our study showed that the majority of individuals were in action or maintenance phase after just a few MI sessions.

Over 80% of all participants participated in health-promotion activities, which was high compared to the 33% reported in a review (32). Determinants for participation as shown by Rongen et al (33) are expected participation by colleagues and supervisors and a positive attitude regarding the importance of such programs. Both are likely to have influenced the high participation in health activities in this study. The additional 8% participation in the extensive group could have been due to the blended approach, which is in line with other studies reporting more pronounced effects if the web-based intervention was offered in combination with face-to-face support (34, 35). This suggests that adding doctor’s face-to-face involvement to purely eHealth improves the likelihood of improvements in health behavior.

More sessions of MI with better quality led to increased participation in health-promotion activities. This is in line with the findings of Lundahl et al (36). In order to facilitate appropriate planning of MI sessions, clients and OP could introduce supportive eHealth technologies (37, 38). However, for long-term participation in health activities, increased MI quality appeared essential, which is in line with Fjeldsoe’s suggestion that face-to-face contact may be a crucial factor in the period after initiation of behavior change (39). Particularly the MI techniques “asking open questions” and “giving direction” enhanced participation in health-promotion activities. Barriers to asking more open-ended questions versus closed-ended questions could have been a gradual decrease of performance level after MI training, a lack of skills or a lack of consultation-time. Changes in MI performance over time were not found, most probably due to the introduced feedback on audio-recordings during the study period (40, 41). Nevertheless, MI quality could be increased by advanced training. This could also solve the perceived lack of time, since for advanced MI coaches regular consultation time is sufficient for achieving behavior change (42). “Giving direction” by influencing the direction of the session towards the target behavior in an MI adherent way was the strongest component in increasing the likelihood of changing health behavior. Previous literature suggested that “empathy” (21, 43), “MI adherence” (19), or “MI spirit” (44) are the most promising mechanisms of MI, but these studies did not include “giving direction” as a therapist behavior component (10). Overcoming the differences between OP in global scoring such as “direction”, would further increase the effectiveness. The variance for global scores showed differences between OP in mastering global scoring, and the global level by OP varied between clients. Detailed information on OP characteristics in relation to level of mastery of the MI technique would be useful to optimize MI training for OP. Information on OP’s client evaluations of MI performance would provide insight into the differences within OP. Furthermore, the MITI coding could have attributed to these differences since reliability of coding for global scores was lower than for behavioral counts, as was previously reported in another study (45). Thus, coders should consider discussing global scores for agreement and include client’s perception in rating MI, for example by using the client evaluation of MI (CEMI) scale (46). In future interventions, all aspects of MI quality should be integrated and mastered, and applied in a feasible number of MI sessions for achieving sustainable health behavior changes. This would require introducing a personalized approach for the number of sessions prescribed, in combination with efforts to increase MI quality.

Strengths of this study included the controlled design, objective measuring of both quality of the intervention implementation and effect measurements, and the adequate OP training. Analyses of intervention details and the behavioral components provided insight into which characteristics of the implementation process contribute to higher effectiveness of the WHP, and what could be addressed in future implementation. Another strength was that the implementation took place in a real-life setting, and was administered by OP familiar with organizational aspects, such as culture, workplace health risks, and on-site options for health activities. This made it easier to incorporate suggested intervention improvements, and other large organizations could benefit from these lessons learned by this study.

A limitation of the study was the use of self-reported measures of participation in health promotion activities. The use of accelerometers and more objective dietary measures could have improved our understanding of behavioral changes associated with the intervention. However, this would have required more time and effort from participants, which could lead to non-adherence with follow-up measurements. Another limitation was the risk of selection bias as participants who received higher quantity of MI showed a higher response at follow-up, which was also found for “giving direction” (data not shown). However, since 78% responded to follow-up at 6 and/or 12 months, a fair picture of the intervention is expected. Last, the impact of organizational factors on individual health behavior was not considered in this study.