Suicide is a public health crisis of staggering proportions. Globally, the annual suicide rate is 10.5 per 100 000 people, resulting in an estimated 793 000 suicide deaths worldwide (1). The suicide rate in South Korea is the 10th highest in the world and the 2nd highest of any nation in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (1, 2). While only a fraction of people who experience suicidal ideation will go on to die by suicide, suicidal ideation is a key “upstream” indicator of suicide risk. Therefore, from a public health perspective, it is worthwhile to investigate the risk factors of suicidal ideation so they can be modified to assist in suicide prevention (3, 4).

Common adverse working conditions, such as high job demands, low job control, effort–reward imbalance, inadequate social support, job insecurity, organizational injustice, and discomfort in an organizational climate can have negative effects on mental health (5–10). There is also evidence that improved working conditions are linked to better mental health (11). Since poor mental health contributes greatly to the development of suicidal ideation, it is important to investigate the relationship between work stress and suicidal ideation for improving specific adverse working conditions to help prevent suicide.

There have been many studies on the relationship between work stress and suicide. However, these studies were limited by various methodological challenges: some used a cross-sectional design (12–16) while others only included certain subgroups (14–17), and still others lacked systematic information regarding work stress (18, 19). Furthermore, considerations of possible confounding factors have differed widely across studies. According to a current meta-analysis and systematic review, high job demands, insufficient job control, effort–reward imbalance, inadequate social support, job insecurity, and role conflict are significantly associated with suicidal ideation (20). However, most studies in this review were cross-sectional, thus leading to the possibility of inflated associations and reverse causality.

Furthermore, gender and age are crucial influences on the relationship between work stress and suicidal ideation. Although some occupational health researchers have included gender as a major variable of investigation (21–23), relatively little attention has been paid to understanding how aging and adult development relate to work motivation.

Accordingly, using the data from a large Korean cohort study, this study investigated whether work stress – including high job demands, insufficient job control, inadequate social support, job insecurity, organizational injustice, and a lack of reward and/or discomfort in an organizational climate – significantly affect new-onset suicidal ideation. In addition, we investigated whether work stress and suicidal ideation may result from multiple, interacting processes related to chronological age and gender. Therefore, the data in this study were stratified in groups according to gender and age and their impact on the relationship between work stress and suicidal ideation was examined.

Methods

Study population

This study was part of the Kangbuk Samsung Health Study, a cohort study of South Korean men and women aged ≥18 years who had previously undergone a comprehensive annual or biennial health examination at the health promotion centers of Kangbuk Samsung Hospital in Seoul and Suwon, South Korea. Over 80% of participants were employees of various companies or local government organizations and their spouses. In South Korea, the Industrial Safety and Health Law guarantees all employees annual or biennial health screenings free of charge, and this workplace health screening examination is mandatory. The remaining participants (<20%) were screened voluntarily. The nature and basic procedures of the Kangbuk Samsung Health Study have been described in the aforementioned studies (24, 25).

The Institutional Review Board of Kangbuk Samsung Hospital approved this study’s protocol (KBSMC 2019-01-042). Informed consent requirement was waived because only de-identified data routinely collected during health screening visits were used.

Selection of a “healthy” sample at baseline

Participants in this study consisted of 95 356 Korean employees aged ≥18 who underwent at least two comprehensive health examinations at the health promotion centers of Kangbuk Samsung Hospital in Seoul and Suwon, South Korea, from January 2012 to December 2017. To improve the confidence of the direction of any associations found, participants who reported having experienced any of the following exclusion criteria were excluded at baseline: experienced suicidal ideation, scored ≥21 on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Rating Scale for Depression (CES-D) (26), scored ≥16 on the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (27), had a psychiatric disorder, or took psychiatric medications. The higher cutoff points of CES-D (≥21) than those of Western countries are due to the different documented ways in which depression is expressed in cultures based on Confucian ethics (26). Participants who had been diagnosed with a medical illness that could affect suicidal ideation were also excluded. Such diagnoses included significant neurologic illnesses (stroke, brain hemorrhage, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease), cardiopulmonary diseases (angina, myocardial infarction, heart failure, heart valve disease, emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and asthma), gastrointestinal disease (inflammatory bowel disease), liver disease (liver cirrhosis), renal disease (chronic renal disease), or thyroid disease (hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism) (28–40). Several individuals met more than one exclusion criterion, and the total number eligible for this study was 75 786 (figure 1).

Measurement of work stress at baseline

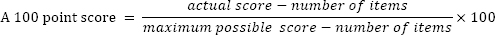

Work stress was measured using the Korean Occupational Stress Scale-Short Form (KOSS-SF), a self-reported questionnaire for estimating work stress among Korean employees. In the National Study for Development and Standardization of Occupation Stress (NSDSOS project), a nation-wide epidemiological study conducted in South Korea by Chang et al (41), the reliability of the KOSS-SF was validated. The seven subscales of KOSS-SF are as follows: high job demands (four items, Cronbach’s alpha: 0.58), insufficient job control (four items, Cronbach’s alpha: 0.67), inadequate social support (three items, Cronbach’s alpha: 0.55), job insecurity (two items, Cronbach’s alpha: 0.73), organizational injustice (four items, Cronbach’s alpha: 0.67), lack of reward (three items, Cronbach’s alpha: 0.72), and discomfort in an organizational climate (four items, Cronbach’s alpha: 0.71) (supplementary material, www.sjweh.fi/show_abstract.php?abstract_id=3852). Each item was scored using Likert-type scoring (1=strongly disagree, 2=disagree, 3=agree, 4=strongly agree). The scores of the total and subscale were converted using a hundred-point system.

Based on the median of the converted scores proposed by Chang et al (41), participants were dichotomized into “high-stress” and “low-stress” groups.

Assessment of suicidal ideation

Suicidal ideation was assessed using the self-reported questionnaire. The questions are a part of the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) (42). The KNHANES is conducted annually by the South Korean government to analyze the level of public health and to compile relevant statistics for implementing and evaluating public health policies. To assess suicidal ideation, participants were asked a yes/no question regarding whether they had ever seriously thought of committing suicide in the past year (“Over the last year, have you ever felt that you would be better off dead?’’).

Potential confounding variables

Self-reported questionnaires included items regarding gender, age, center (Seoul or Suwon), marital status [categorical variable: never married (reference)/married/others], education [categorical variable: less than middle school degree (reference)/high school degree/college degree or higher], income [categorical variable: >$4000/month (reference)/<$4000/month/others], alcohol consumption [continuous variable: total score on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT)], smoking status [categorical variable: never smoked (reference)/former smoker/current smoker], medication history [categorical variable: yes/no (reference)], and personal medical history [categorical variable: yes/no (reference)]. The Korean version of AUDIT was used to measure participants’ alcohol consumption (43). Personal medical history included diagnoses of significant neurologic, cardiopulmonary, gastrointestinal, liver, renal, and thyroid disease. Weight and height were calculated to the nearest 0.1 cm and 0.1 kg, respectively, using an InBody 720 machine (Biospace, Seoul, South Korea). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight by height (kg/m2).

Questionnaires included some items relating to occupational characteristics: type of employment [categorical variable: full-time (reference)/part-time] and shift work [categorical variable: yes/no (reference)]. Average weekly work time was categorized into 3 groups [categorical variable: ≤40 (reference)/41–50/≥51 hours/week].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the participants’ characteristics according to the development of suicidal ideation. The primary endpoint was the development of suicidal ideation. Each participant was followed from the baseline examination until the development of suicidal ideation or until the last health examination conducted prior to 31 December 2017. The incidence rate was calculated by dividing the number of incident cases by the total number of person-years of follow-up. The relationship between baseline work stress and incidence of suicidal ideation was evaluated using the Cox proportional hazards models, which are used to estimate adjusted hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). All statistical models were adjusted for age, center (Seoul or Suwon), marital status, education, income, alcohol consumption, smoking status, BMI, total KOSS score, type of employment, shift work, and average work time at baseline. According to Levinson’s developmental approach to adult socialization (44), age was classified into three groups: early adulthood (18–35 years); midlife decade (36–44 years); and middle-aged and older adulthood (≥45 years). Data were stratified by gender and age subgroups to consider their impacts on the relationship between work stress and the development of suicidal ideation.

We then performed sensitivity analyses. To determine if there were misclassified cases due to irregular follow-up intervals, we restricted analyses to the development of suicidal ideation after three years of follow-up. Using logistic regression, we examined the relationship between work stress at baseline and the risk of suicidal ideation three years later.

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 14.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA). All P-values were two-tailed. P-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

From a total of 289 706 person-years of follow-up, 3460 participants developed suicidal ideation (an incident rate of 1.2%). The average follow-up period was 3.82 years. Table 1 displays the baseline characteristics of employees according to their risk of suicidal ideation. For both genders, groups with suicidal ideation reported lower levels of education and higher levels of overall work stress. For the male workers, the groups that expressed suicidal ideation reported lower income, higher AUDIT scores, and were likelier to be current smokers. Job characteristics of participants according to their risk of suicidal ideation are presented in table 2. Type of employment, shift work, and average work time differed in their effects by gender; male workers who worked long hours (≥51 hours/week) and female workers in part-time jobs and day work demonstrated a higher frequency of suicidal ideation.

Table 1

Baseline characteristics of 59 014 male and 16 772 female employees in South Korea. [AUDI=Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; BMI=body mass index]

Table 2

The relationship between occupational stress and suicidal ideation in 59 014 male employees. [CI=confidence interval.]

| Work stress | Person-years (PY) | Number of cases | Cases per 10 000 PY | Crude HRa(95% CI) | Multivariable-adjusted HRb (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High job demands | |||||

| Low | 129 842.8 | 1197 | 92.2 | 1.15 (1.06–1.25) | 1.18 (1.08–1.29) |

| High | 99 171.8 | 1191 | 120.1 | ||

| Insufficient job control | |||||

| Low | 209 385.7 | 2116 | 101.1 | 1.14 (1.00–1.30) | 1.10 (0.96–1.26) |

| High | 19 628.9 | 272 | 138.6 | ||

| Inadequate social support | |||||

| Low | 30 007.7 | 267 | 89.0 | 0.99 (0.87–1.31) | 0.98 (0.86–1.12) |

| High | 199 006.9 | 2121 | 106.6 | ||

| Job insecurity | |||||

| Low | 201 525.2 | 1957 | 97.1 | 1.35 (1.21–1.51) | 1.32 (1.18–1.48) |

| High | 27 489.3 | 431 | 156.8 | ||

| Organizational injustice | |||||

| Low | 194 878.2 | 1832 | 94.0 | 1.27 (1.13–1.42) | 1.25 (1.11–1.41) |

| High | 34 136.4 | 556 | 162.9 | ||

| Lack of reward | |||||

| Low | 181 946.4 | 1658 | 91.1 | 1.30 (1.17–1.44) | 1.32 (1.19–1.47) |

| High | 47 068.2 | 730 | 155.1 | ||

| Discomfort in an organizational climate | |||||

| Low | 137 484.7 | 1153 | 83.9 | 1.33 (1.22–1.45) | 1.35 (1.24–1.48) |

| High | 91 529.8 | 1235 | 134.9 |

Table 3 shows the results for the relationship between work stress and the risk of suicidal ideation according to gender. For men, high job demands (HR 1.18, 95% Cl 1.08–1.29), job insecurity (HR 1.32, 95% Cl 1.18–1.48), organizational injustice (HR 1.25, 95% Cl 1.11–1.41), lack of reward (HR 1.32, 95% Cl 1.19–1.47) and discomfort in their organizational climate (HR 1.35, 95% Cl 1.24–1.48) were significantly associated with the onset of suicidal ideation. For women, insufficient job control (HR 1.22, 95% Cl 1.05–1.42) and discomfort in their organizational climate (HR 1.27, 95% Cl 1.11–1.45) were significantly associated with the development of suicidal ideation.

Table 3

The relationship between occupational stress and suicidal ideation in 16 772 female employees. [CI=confidence interval; HR=hazard ratio.]

| Work stress | Person-years (PY) | Numbers of cases | Cases per 10 000 PY | Crude HRa (95% CI) | Multivariable-adjusted HRb (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High job demands | |||||

| Low | 37 055.0 | 630 | 170.0 | 1 | 1 |

| High | 23 636.3 | 442 | 187.0 | 1.05 (0.93–1.19) | 1.07 (0.94–1.22) |

| Insufficient job control | |||||

| Low | 46 214.6 | 774 | 167.5 | 1 | 1 |

| High | 14 476.6 | 298 | 205.8 | 1.24 (1.08–1.43) | 1.22 (1.05–1.42) |

| Inadequate social support | |||||

| Low | 8 708.9 | 118 | 135.5 | 1 | 1 |

| High | 51 982.3 | 954 | 183.5 | 1.23 (1.01–1.49) | 1.19 (0.98–1.45) |

| Job insecurity | |||||

| Low | 22 267.2 | 364 | 163.5 | 1 | 1 |

| High | 38 424.0 | 708 | 184.3 | 1.06 (0.93–1.20) | 1.00 (0.88–1.14) |

| Organizational injustice | |||||

| Low | 49 885.1 | 834 | 167.2 | 1 | 1 |

| High | 10 806.2 | 238 | 220.2 | 1.15 (0.98–1.35) | 1.08 (0.91–1.29) |

| Lack of reward | |||||

| Low | 43 980.9 | 728 | 165.5 | 1 | 1 |

| High | 16 710.3 | 344 | 205.9 | 1.04 (0.90–1.21) | 1.01 (0.86–1.18) |

| Discomfort in an organizational climate | |||||

| Low | 34 506.1 | 536 | 155.3 | 1 | 1 |

| High | 26 185.2 | 536 | 204.7 | 1.22 (1.07–1.39) | 1.27 (1.11–1.45) |

To consider the effects of age on work stress and the risk of suicidal ideation, data were additionally stratified according to age groups. Table 4 represents the results for the adjusted relationship between work stress and incidence of suicidal ideation across the lifespan for men, while table 5 shows the results for women. For male workers, high job demands and lack of reward were associated with the onset of suicidal ideation from early adulthood to the midlife decade (high job demands in early adulthood: HR 1.22, 95% Cl 1.05–1.41; high job demands in the midlife decade: HR 1.27, 95% Cl 1.12–1.44; lack of reward in early adulthood: HR 1.33, 95% Cl 1.12–1.59; and lack of reward in the midlife decade HR 1.43, 95% Cl 1.22–1.68). Job insecurity was associated with suicidal ideation from the midlife decade (HR 1.36, 95% Cl 1.16–1.60) to middle-aged and older adulthood (HR 1.42, 95% Cl 1.11–1.81). Organizational injustice was associated with suicidal ideation in middle-aged and older adulthood (HR 1.68, 95% Cl 1.24–2.28). Discomfort in an organizational climate was associated with suicidal ideation across the entire lifespan as follows: early adulthood: HR 1.34, 95% Cl 1.16–1.56; midlife decade: HR 1.31, 95% Cl 1.15–1.49; middle-aged and older adulthood: HR 1.51, 95% Cl 1.22–1.86. For women, the results for organizational injustice (HR 1.26, 95% Cl 1.01–1.58) and discomfort in an organizational climate (HR 1.42, 95% Cl 1.18–1.70) were associated with suicidal ideation in early adulthood. The results from the midlife decade to middle-aged and older adulthood for female workers were not statistically significant.

Table 4

Age differences in the relationship between occupational stresses and suicidal ideation among 59 014 Korean male employees. [CI=confidence interval; HR=hazard ratio.]

| Work stress | Early adulthood, 18–35 years (N=22 223) | Midlife decade, 36–44 years (N=26 120) | Middle-aged and older, ≥4 5 years (N=10 671) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Crude HRa (95% CI) | Multivariable-adjusted HRb (95% CI) | Crude HRa (95% CI) | Multivariable-adjusted HRb (95% CI) | Crude HRa (95% CI) | Multivariable-adjusted HRb (95% CI) | |

| High job demands | 1.20 (1.05–1.38) | 1.22 (1.05–1.41) | 1.24 (1.09–1.39) | 1.27 (1.12–1.44) | 0.87 (0.70–1.08) | 0.91 (0.73–1.14) |

| Insufficient job control | 1.16 (0.96–1.39) | 1.08 (0.89–1.31) | 1.19 (0.96–1.47) | 1.16 (0.93–1.44) | 0.97 (0.66–1.45) | 0.86 (0.57–1.31) |

| Inadequate social support | 0.89 (0.73–1.08) | 0.89 (0.73–1.08) | 1.04 (0.85–1.28) | 1.04 (0.85– 1.28) | 1.14 (0.81–1.60) | 1.11 (0.79–1.56) |

| Job insecurity | 1.23 (1.01–1.50) | 1.22 (0.99–1.50) | 1.36 (1.16–1.59) | 1.36 (1.16–1.60) | 1.48 (1.17–1.88) | 1.42 (1.11–1.81) |

| Organizational injustice | 1.26 (1.06–1.50) | 1.21 (1.00–1.46) | 1.15 (0.97–1.36) | 1.16 (0.97–1.39) | 1.79 (1.34–2.37) | 1.68 (1.24–2.28) |

| Lack of reward | 1.34 (1.14–1.59) | 1.33 (1.12–1.59) | 1.39 (1.19–1.62) | 1.43 (1.22–1.68) | 0.95 (0.72–1.24) | 0.96 (0.72–1.27) |

| Discomfort in the organizational climate | 1.33 (1.15–1.55) | 1.34 (1.16–1.56) | 1.29 (1.14–1.47) | 1.31 (1.15– 1.49) | 1.46 (1.18–1.80) | 1.51 (1.22–1.86) |

Table 5

Age differences in the relationship between occupational stresses and suicidal ideation among 16 772 Korean female employees. [CI=confidence interval; HR=hazard ratio.]

| Work stress | Early adulthood, 18–35 years (N=10 058) | Midlife decade, 36–44 years (N=5577) | Middle-aged and older, ≥45 years (N=1137) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Crude HRa (95% CI) | Multivariable-adjusted HRb (95% CI) | Crude HRa (95% CI) | Multivariable-adjusted HRb (95% CI) | Crude HRa (95% CI) | Multivariable-adjusted HRb (95% CI) | |

| High job demands | 0.99 (0.84–1.17) | 1.01 (0.85–1.20) | 1.16 (0.94–1.42) | 1.20 (0.96–1.50) | 1.15 (0.73–1.81) | 1.13 (0.68–1.87) |

| Insufficient job control | 1.18 (0.98–1.41) | 1.21 (0.99–1.47) | 1.40 (1.10–1.78) | 1.24 (0.96–1.61) | 1.25 (0.77–2.03) | 0.85 (0.50–1.46) |

| Inadequate social support | 1.20 (0.93–1.55) | 1.22 (0.94–1.57) | 1.13 (0.82–1.57) | 1.13 (0.82–1.57) | 1.98 (0.72–5.47) | 1.93 (0.70–5.37) |

| Job insecurity | 1.06 (0.89–1.26) | 1.02 (0.85–1.22) | 0.97 (0.78–1.20) | 0.91 (0.73–1.34) | 1.54 (0.95–2.51) | 1.53 (0.91– 2.55) |

| Organizational injustice | 1.26 (1.03–1.55) | 1.26 (1.01– 1.58) | 0.93 (0.71–1.24) | 0.85 (0.62–1.15) | 1.23 (0.71– 2.15) | 0.79 (0.42– 1.49) |

| Lack of reward | 1.02 (0.84–1.24) | 1.02 (0.83–1.25) | 1.13 (0.88–1.45) | 1.07 (0.82–1.40) | 1.02 (0.60– 1.73) | 0.84 (0.47–1.50) |

| Discomfort in the organizational climate | 1.38 (1.16–1.64) | 1.42 (1.18–1.70) | 1.04 (0.84–1.29) | 1.10 (0.87–1.37) | 1.30 (0.82–2.04) | 1.09 (0.67–1.78) |

There was evidence of interaction by gender in the association between some components of work stress and the risk of suicidal ideation, and the relationship was stronger for men than for women (job insecurity, P<0.001; organizational injustice, P=0.011; lack of reward, P<0.001; discomfort in occupational climate, P=0.044). In addition, there was a positive interaction by age in the relationship between job insecurity and the development of suicidal ideation (P=0.015).

In the sensitivity analyses for examining the relationship between work stress at baseline and the risk of suicidal ideation three years late, the results were similar.

Discussion

Differences in the relationship between work stress and the risk of suicidal ideation according to gender

This study’s use of subscales to measure work stress revealed that more factors contributed to the risk of males developing suicidal ideation than females. These differences may be explained by gender roles and gender-oriented segregation in the workforce (45–47). According to the expectations of cultural gender roles, women are responsible for unpaid work in the family, such as childrearing, as well as paid work. Men tend to focus on paid work because their self-identity is often derived from the breadwinner role (48). Therefore, male employees could be more vulnerable to external social and economic stressors related to the workplace than female employees (49). Milner et al (15) examined the relationship between work stress and suicidal ideation, using data from the Australian Longitudinal Study on male health. They reported that low job control, effort-reward imbalance (ERI), and job insecurity were significantly associated with suicidal ideation, which is partially consistent with our results. However, our study found only a weak and statistically not significant association between low job control and the risk of suicidal ideation in men. In women, though, this association was stronger. Milner et al (15) used a cross-sectional study design and analyzed Australian male workers, who are culturally different from Korean male employees.

Although more men than women felt pressured due to most components of work stress, insufficient job control contributed more to female employees’ risk of developing suicidal ideation than to male employees’ risk. According to 2015 reports by Statistics Korea (50), the time dual-earner husbands spent on household labor was half that of their wives (men: 8 hours/week; women: 19.7 hours/week). Inequities in household labor distribution is observed not only in East Asia but also in certain countries in northern Europe and North America (51, 52). Therefore, for female employees, it may be crucial to control workpace and schedules to reduce work–family conflicts.

Despite the gender differences in work stress associated with the development of suicidal ideation, discomfort in an organizational climate showed strong associations with the onset of suicidal ideation for both males and females. In the context of the Korean culture, discomfort in an organizational climate may be reflected by dining out after work, inconsistent job order, authoritarian atmospheres, and gender discrimination (41). Compared with western organizations, Korean companies may tend to have more hierarchical and authoritarian atmospheres due to collectivist and Confucian influences (9, 10). Irrespective of gender, when individuality, rationality, and gender equality were ignored in the workplace, employees could feel pressured to the point that they experienced suicidal ideation.

Age differences in the relationship between work stress and the risk of suicidal ideation among male employees

Apart from gender differences, age differences pertaining to the relationship between work stress and the development of suicidal ideation were found too. Conventionally, young adulthood is the time when people choose an occupation and embark on a career. As young male workers learn to fit into the working environment, they are likely to subjectively perceive their workload as exceeding their coping abilities (53, 54). At the start of their careers, young workers are often trapped in a low-salary working environment despite their increasing desire to attain economic independence; therefore, they may feel pressured due to a lack of reward (54). The midlife decade groups may demonstrate more resilience when adapting to changing environments and coping with various problems (54, 55). Since they tended to demonstrate greater autonomy, larger workloads were delegated to them. In addition, as most participants in this group were married and had established family relationships, they were required to juggle the demands of work and family (53). Therefore, high job demands can emerge as a potential risk factor for suicidal ideation in male workers in the midlife decade groups.

The midlife decade groups bore the responsibility of the breadwinner role; therefore, job insecurity had the potential to serve as a stressor to the point of suicidal ideation (53). A previous study reported that younger employees displayed strong achievement motives relating to rewards, while middle-aged and older adults recalibrated their motives from individual achievement to supervisory and managerial roles (56). “Fairness of exchange” provides a conceptual background similar to ERI and organizational injustice. However, ERI is thought to operate on the individual level and in relation to rewards, whereas organizational injustice operates on the organizational level and in relation to other employees (57). In the context of this age-related change in values regarding work motives and roles, the midlife decade groups were potentially under pressure due to a lack of reward, while middle-aged and older workers (who carried a greater responsibility for subordinates and the organization as a whole, rather than emphasizing individual performance and achievement) experienced stress related to issues of organizational justice such as policy, support, and communications. Our results showed that job insecurity was also associated with the risk of suicidal ideation among middle-aged and older workers. According to Hempstead et al (58), among adults aged 40–60 years, the most common suicide risk factors are job and financial problems, which are consistent with our results. Middle-aged and older employees close to voluntary or involuntary retirement age often have the additional burden of caring for both their children and aging parents. In addition, the proportion of their medical expenditure on themselves is also increasing. Therefore, job insecurity can be potentially a crucial risk factor for suicidal ideation among middle-aged and older workers (59).

Given that discomfort in the organizational climate was found to be associated with the development of suicidal ideation across the entire lifespan, it can be conjectured that this subscale was associated with particular Korean cultural customs rather than the characteristics of any specific age group. In Korea, collectivism, which stresses human interdependence and the importance of the collective, may be reflected in the hiring process, task arrangement, evaluation, and promotion (10). Accordingly, individuals with personal connections to company insiders and high-ranking outsiders, high-handed administrative personnel, or alumni of the same school are favored. This hierarchical and authoritarian approach may also potentially contribute to the development of suicidal ideation in male employees.

Age differences in the relationship between work stress and the risk of suicidal ideation among female employees

In young female workers, discomfort in an organizational climate and organizational injustice were found to be significantly associated with the development of suicidal ideation. Despite the increase in educational and occupational opportunities, many women still suffer from gender discrimination in terms of pay, promotions, and access to resources – a situation which, in Korea, stems from Confucianism (9, 10). In this discriminatory atmosphere, young female workers are more likely to perceive organizational policies and operational systems in their workplace as “unreasonable” or “unfair” than their male counterparts (9, 60). Therefore, discomfort in the organizational climate and organizational injustice can be considered risk factors for suicidal ideation for young women. Whereas young female workers are stressed out due to the organizational system and atmosphere stemming from gender discrimination, young male workers tend to feel pressured due to individual performance and achievement (eg, their workload exceeding their coping abilities or their desire to attain economic independence). For female workers aged ≥35 years, no significant association between work stress and suicidal ideation was found. These results can be explained within the context of gender roles and lifespan development. According to conventional gender roles, women’s responsibilities are divided into unpaid labor (such as childrearing and household chores) and paid employment, which may lead to lower expectations for job control and stability (48). In terms of lifespan development, older female workers tend to be more resilient than younger women when confronted with work–family conflicts and workload stress (54). In addition, as workers age, the preeminence of achievement motives appears to decline while motives related to promoting positive affect and protecting self-concept increases (56). Lastly, one methodological aspect must be noted: since considerably fewer women were sampled than men, the statistical power of the analyses might have decreased during the stratification process.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several strengths. First, to the best of our knowledge, this study examined the relationship between work stress and the development of suicidal ideation using the largest cohort to date. Second, to reduce the risk of reversal causality, this study tried to select a healthy sample without any evidence of current physical illness, psychiatric disease, and/or depressive or anxiety symptoms at baseline. Third, many covariates related to suicidal ideation were included in this study, which allowed for a meaningful analysis. Finally, to consider the effects of gender and age on the relationship between work stress and the risk of suicidal ideation, data were stratified accordingly, enabling the estimation of gender and age-specific factors related to work stress to be monitored and modified by mental health professionals.

The results of this study should be interpreted with caution due to its limitations. First, since work stress and suicidal ideation were measured using self-reported questionnaires, the results could be affected by response bias. Second, our data allowed the examination of only suicidal ideation as an outcome. Data on potential subsequent outcomes (eg, suicidal attempts) or more objectively assessed outcomes (eg, suicide mortality data) would also be desirable. However, many studies have suggested that suicidal ideation is associated with suicidal attempt as well as exact prevalence suicide events (61, 62). In addition, existing studies have revealed that suicidal ideation is a distinct risk factor of actual suicide, while lethargy associated with depressive symptoms may be a protective factor against suicide attempts (63). Therefore, in terms of suicide prevention, prevention of suicidal ideation may prelude serious suicide attempts or events. Third, certain covariates contributing to suicidal ideation were missing from this study, including occupation type, company size, and duration of employment. Fourth, because of the uneven distribution of male and female participants and the low incidence of suicidal ideation observed, this study lacked sufficient statistical power to investigate whether the risks of suicidal ideation caused by work stress were disproportionately present in the female worker groups. Fifth, although our study selected individuals not suffering from suicidal ideation and psychiatric disorders at baseline, it is not clear if the onset of suicidal ideation was the first or a recurrent onset. Sixth, since a large proportion of the sample were employees who undertook mandatory health screening examinations by the Industrial Safety and Health Law, there is a possibility of selection bias. However, information about whether health examinations were mandatory or spontaneous is not available, and it is not possible to control for it. Future research should include the characteristics of health examinations as covariates. Seventh, the internal consistency reliability for high job demands (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.58) and inadequate social support (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.55) was not strong, and we cannot be certain that the exposure measurements used for these two aspects have been sufficiently validated to accurately measure the association between work stress and suicidal ideation. Eighth, this study had a relatively short follow-up period, which could be lead to reverse causality. Lastly, generalization of our findings to other countries may be difficult due to South Korea’s unique characteristics.

Concluding remarks

This study examined components of work stress associated with the incidence of suicidal ideation in a large cohort of healthy Korean employees. In addition, considering the effects of age and gender on the relationship between work stress and suicidal ideation, the data were stratified, and age- and gender-specific work stress associated with suicidal ideation was identified. Since Korean employees may be under pressure of an authoritarian and discriminatory atmosphere stemming from collectivism and Confucianism, government policy and workplace regulations should attempt to create an egalitarian environment in the workplace. In case of male employees, companies can help young adult and midlife decade groups achieve individual performance and motivation, and governmental policies can focus on providing job security to the breadwinner. In case of female employees, it is important to make policies and regulations to reduce gender discrimination in the workplace.

To confirm these results and improve overall understanding, additional studies examining other ethnic groups and the underlying mechanisms between work stress and incidences of suicidal ideation are needed.